Right on cue, the Chinese have restarted “devaluation.” Because no one ever learns, and because trade wars are a conveniently timed distraction, CNY’s dramatic plunge below 7.00 is being written up as currency manipulation. It is manipulation, just nothing like what’s being described. PBOC Governor Yi Gang is a passenger here, not the man pulling the levers behind the scenes.

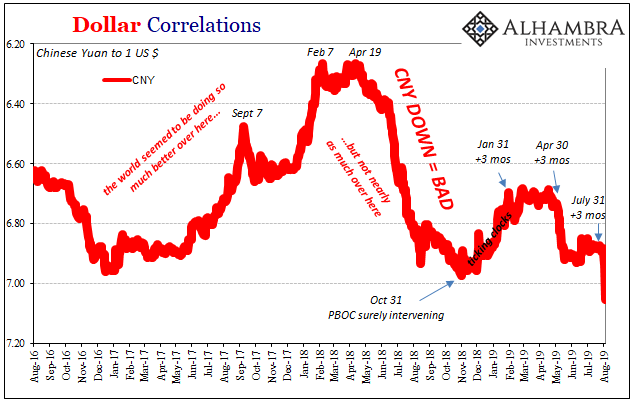

In the mainstream, it’s like August 2015 never happened. Or early 2014 for that matter. Five and a half years ago, “everyone” had expected China’s currency to keep accelerating upward. But as 2013 turned to 2014 (the very same time UST nominal yields began to fall again) CNY abruptly reversed course.

A minor fluctuation or two is to be expected in the messy world of global “hot money.” This was something else, however, and it wasn’t long before the PBOC began to react – and the world taking note while puzzled by the reactions. As one of its first countermeasures, China’s central bank widened the daily trading range for CNY.

Prior to July 2005, the exchange value had been pegged to around 8.2765 RMB to the US dollar. Misunderstanding the situation back then, too, the Communists were accused of, guess what, currency manipulation. China’s economy had been a miracle of economic growth, the most rapid industrialization ever imagined.

Western officials wanted some of that; or, more precisely, wanted some of it back.

Blaming CNY’s lack of movement for their de-industrialization (the currency was supposedly undervalued), Chinese officials gave in to these Western demands. The currency would be allowed float – somewhat. The PBOC would still control much of the landscape by fixing a daily target (of sorts) and then allowing the market to determine the final “value” within a predetermined range.

It was a crucial misinterpretation. Was CNY rising at the time because the PBOC was trying to make George Bush happy? Or was the dollar falling because there were so many of them floating around offshore the “hot money” was willing to pay any price for access to China’s “miracle?” Most people even today still believe it was the former.

The more relevant question for 2014 and forward has been this: what happens when all that “hot money” wants out?

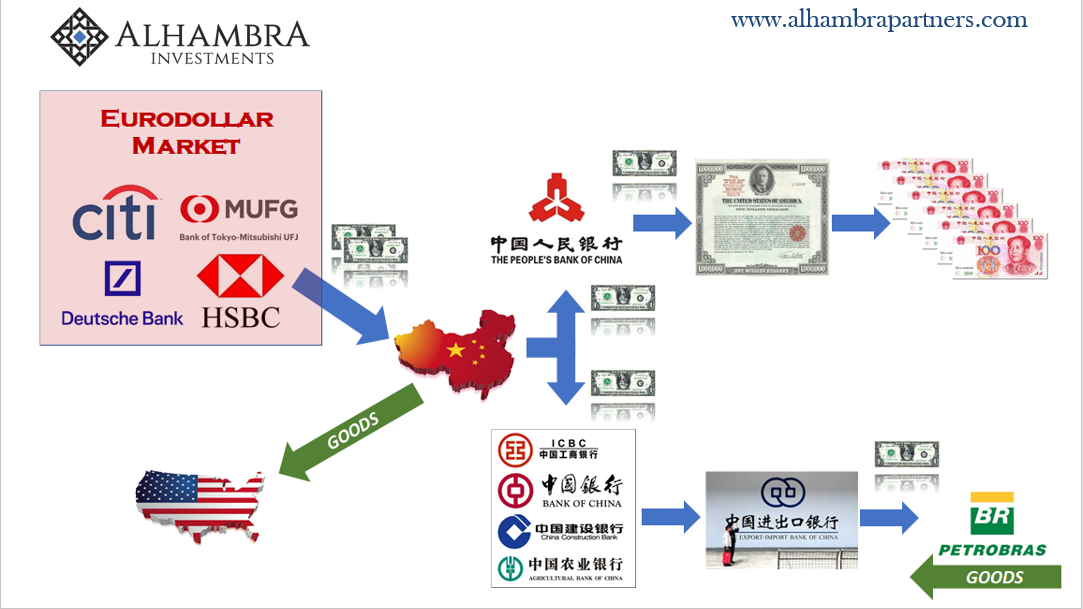

Following the second dollar crisis in 2011, Euro$ #2, China was handed two problems though not quite simultaneously. First, the country’s economy proved to be just as vulnerable as any developed world system to the “new normal” of weak growth. The lack of true recovery in the US and Europe wasn’t thought to be a big deal to Asia and EM’s; until it was.

Once it dawned on the rest of the world that EM growth shouldn’t be taken for granted, the entire global risk profile changed. What had been assumed as can’t-miss sure-things even in 2011 and 2012 were being openly challenged by a global slowdown “no one” saw coming. Higher risk/lower return can be a desperate condition.

But when CNY suddenly switched in early 2014, this was not recognized in mainstream convention. Things were picking up, they said. Though it wasn’t synchronized back then, global growth was supposed to be unequivocally strong. And China was being counted on for much of that strength, the whole world looking forward to it going back to a precrisis miracle mode.

Thus, if the world was on its way to normalization again, how to explain CNY’s obvious backlash?

It took an ever more bizarre turn when in March 2014 the PBOC widened the daily trading band. China’s central bank wasn’t experiencing trouble, no, no, no, officials must be punishing speculators betting too much on it going higher. They were letting the currency fall a little, the theory said, to make sure that once global normalization had been secured CNY’s expected ascent wouldn’t be too unruly.

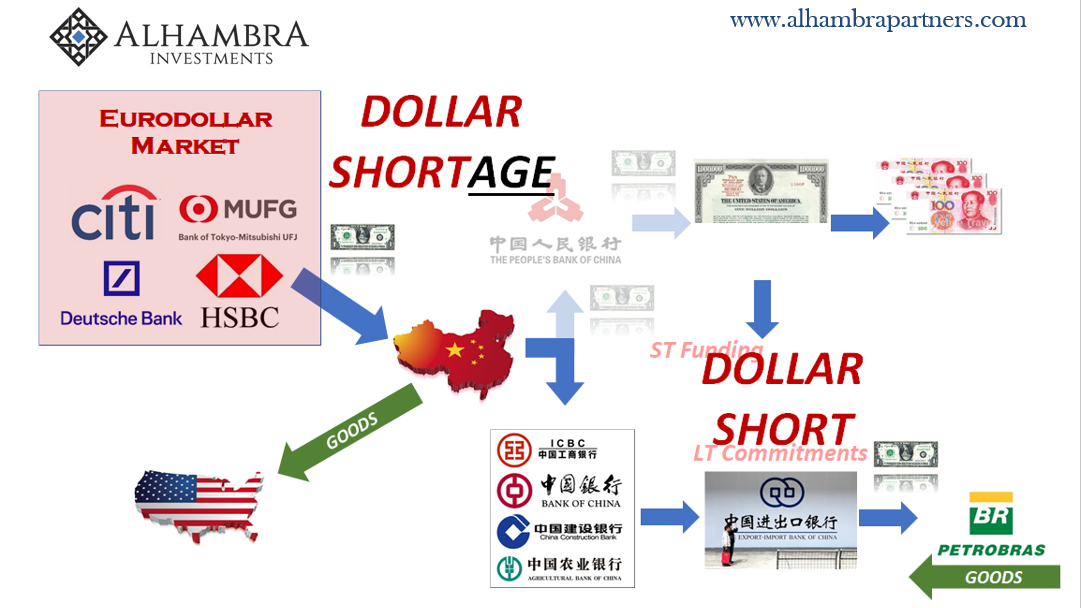

In [this] formulation, the PBOC is directing affairs, sending out “instructions” that Chinese banks should “aggressively purchase dollars” ostensibly to punish those hot money speculators. Given what we know of copper and dollar financing in general, is that really the case? Is it not more likely that the PBOC has lost control of dollar conditions and was forced by the “market” to widen the daily band in order for dollar-starved banks to aggressively bid for dollars they could not otherwise obtain?

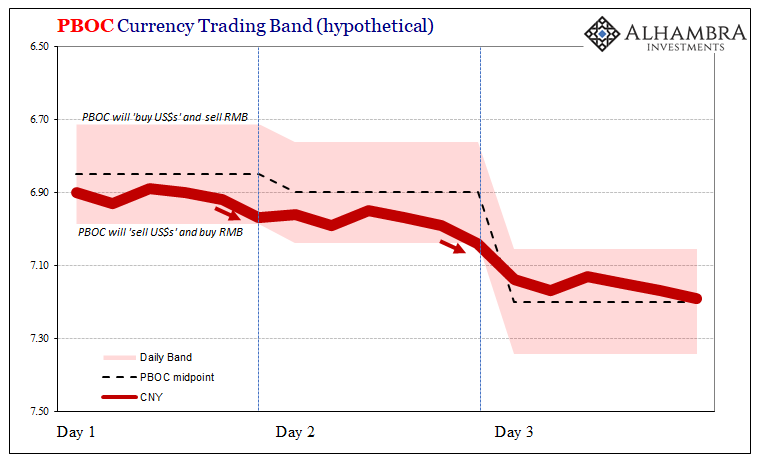

That’s the thing to keep in mind. The daily band is only a daily band if the central bank is acting to enforce its limits. What that means is really pretty simple.

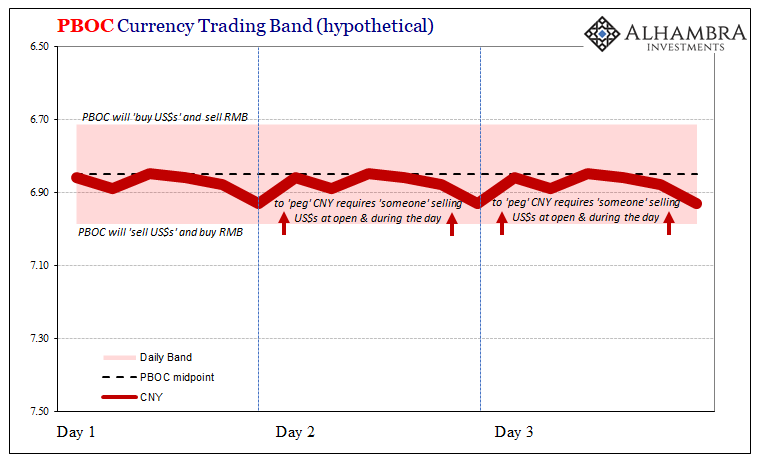

The PBOC maps out a “midpoint” for CNY each day. Consulting with Chinese dealer banks beforehand, the central bank tries to get a sense of trading conditions. Balancing those perceptions against policy goals, authorities pick the midpoint which will define their policy range for that day.

The goal is to select a trading band which will contain market trading without any need for action at either end. If something were to happen during the day’s session, and for some reason the market price of CNY traded higher or lower, the PBOC is obligated to buy or sell US$’s as necessary at the limits. No central bank wants to do that.

Whenever CNY might be especially weak, the market price falling toward the lower limit, China’s central bank will be obligated to “sell US$’s” into the marketplace buying up RMB with them. Another way of saying that is, the PBOC must supply dollars at the lower bound.

By widening the daily band in early 2014, China’s central bank was really acknowledging two factors: 1. There was downward pressure on CNY, so much that it was probably going to lead to ongoing problems with the market price running up against the daily lower limit more frequently, meaning a greater likelihood of intervention maybe even continuing intervention; 2. The PBOC obviously didn’t want to be in a situation where it was forced to “supply dollars” very often. A wider trading band would’ve allowed banks to pay more for dollar funding (lower CNY) without dragging the central bank into the mess.

Why didn’t authorities want to be sucked into the growing dollar issue?

What all this data shows, as opposed to conjecture about the supernatural powers of central banks, is that yuan’s devaluation may be directly tied to dollar shortages. In fact, as I argue here, it is far more plausible that a dollar shortage (showing up as a rising dollar, or depreciating yuan) is forcing the PBOC to allow a wider band in order that Chinese banks can more “aggressively” obtain dollars they desperately need. Worse than that, the PBOC itself cannot meet that need with its own “reserve” actions without further upsetting the entire fragile system.

There are costs to intervention. This is another piece of the puzzle which doesn’t make sense from the conventional perspective. After all, by the end of 2013 China had amassed the largest stockpile of foreign reserves ever contemplated. Multiple trillions were held as insurance against just this kind of problem.

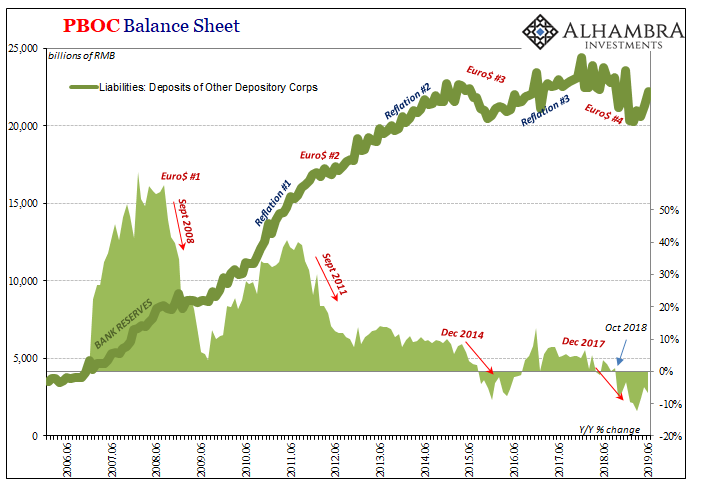

But that view is entirely too simplistic; it doesn’t take any account of the other side of ledger. To take even $1 in assets and use them for CNY means that is $1 fewer assets on the central bank’s balance sheet and therefore $1 less in liabilities meaning currency. That’s the “fragile system” I was writing about five and a half years ago.

The PBOC was being drawn into a battle it was ill-prepared and more so ill-equipped to fight. Why? Because no one had ever conceived of a permanent change to how things worked. To the mainstream, there was this omniscient central bank backed by the greatest amount of financial ammunition ever amassed waging a wise war against speculators to make absolutely certain nothing would interrupt the global recovery.

In reality, including a global recovery that didn’t actually show up, the PBOC was attempting to manage a weakening economy that its officials knew would be made so much worse, reducing currency and money growth at the worst possible time, if they had no other option but to get involved.

They were almost certainly hoping it would all just go away if given enough time and room, counting on Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen’s predictions to come true (for once) and calm the (euro)dollar markets at the time rethinking material risks as they related to China.

As 2014 went on, however, no such luck. Once the calendar turned to 2015, the PBOC was neck deep in “selling UST’s” and therefore cutting back on internal monetary growth (above). They had to find another approach which might steady CNY without using reserves and therefore keeping some room for internal RMB expansion. The economy had to be stabilized, but how to do it without falling back on reserves and therefore RMB contraction?

This is what I call the “ticking clock” which began to show up in March 2015.

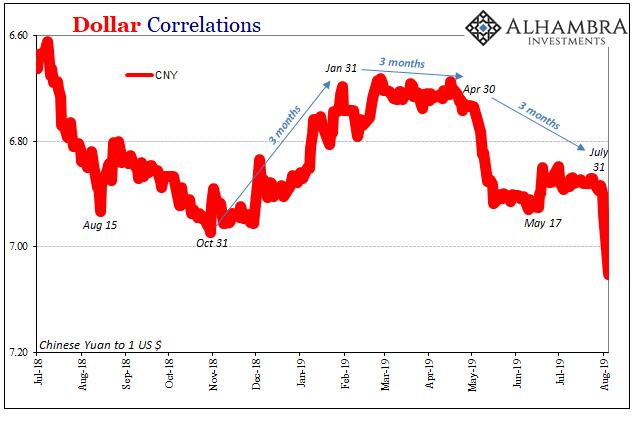

The standard derivative contract is typically three months long, and further termed out contracts are set to expire at three-month intervals.

For the PBOC to achieve a stable CNY exchange value under these conditions requires dollar ammunition. A lot of dollar ammunition. But, if you won’t use any of your reserve stockpile, where else can you go?

Brazil’s central bank in 2013 would write of another way of doing things. It wasn’t anything new, but in the post-2011 world the Brazilians saw a need to pre-justify what they were about to to do given what was coming their way. There are times when a more clandestine approach using “contingent liabilities” is plain necessary. It was as true then for Brazil as it was becoming for China.

A well known advantage of issuing such contingent liabilities as currency swaps is that authorities become able to intervene in the exchange market indirectly, without affecting the money supply or varying the stock of foreign exchange reserves.

Beyond just the daily band, to peg CNY around the midpoint and to keep that midpoint nearly the same every day requires constant vigilance and direct activity. You might amass a war chest of off-balance sheet funds using “contingent liabilities” staggered out at three-month intervals.

In other words, you borrow a ton of US$’s upfront in FX swaps and the like, keeping them off the books (kind of). The first batch of those swaps will be coming due three months from now. The second in six months. And so on.

You use these “contingent liabilities” you’ve gathered ahead of time as fuel, doling it out in piecemeal fashion to fight the daily war to keep CNY close to its midpoint. If you can keep it near the midpoint that also means you can keep the midpoint from moving much day to day. The steadier the exchange value, maybe to the point of it looking like it is pegged, the costlier the output.

If you are being bold, like the PBOC, say, in November 2018, you could even try to engineer a higher CNY – but that’s going to mean using up a lot of ammunition.

The goal is relatively simple: convince the market that nothing is wrong, or at least if there is something wrong it’s not something you can’t handle (and the media will help you out by claiming all these things). The currency appears to be stable, and that will let time heal every wound. Three months from now when the first batches of FX swaps begin expiring, you hope and expect that whatever was bugging the eurodollar markets no longer is.

If on the other hand the eurodollar system is unconvinced by an artificially stable CNY, you’ve just made it worse (the nightmare).

To oversimplify again, let’s assume [local banks] need to borrow $100 every day in short-term eurodollar markets just to keep doing the vital economic and financial things [banks] do. One day, the eurodollar market demands $110 for whatever reasons including problems on its own end. As the central bank, [you] promise to help [them] by giving [them] the extra $10 because [them] not having that $10 means [they] don’t get all of the $100 and therefore all sorts of bad things for you as well as the economy.

[You] can sell $10 in assets [you] already own, which, as noted above, means that’s $10 subtracted from the domestic monetary base. Or, the Brazil option, [you] can give [banks] $10 today by promising to obtain $11 three months in the future. It sounds absurd, but that’s really what happens and it keeps the $10 in place for the domestic base while simultaneously giving [banks] an acceptable liability covering [their] $10 shortfall.

Three months later, [they] are still borrowing the $100 on eurodollar markets as [they] always do, but now [you] have to borrow $11 on top of it, to close out that prior intervention. If the eurodollar market has gone back to normal, great. If the eurodollar market still demands $110 from [them], then [you] have double the problem.

So, you now have these three-month intervals where you have to decide to increase the subsidy you are giving your local banks (the “contingent liabilities” are the basis for you to provide the subsidy of forward cover, the daily ammunition to keep CNY and the midpoint stable) or you have to back off because if you keep doing it the costs will pile up very quickly (and will mean huge RMB contraction in the future).

If you decide you just can’t do it, guess what happens to CNY:

The market price tends to get lower (Chinese banks being asked to pay up for perceived risks) and because you no longer wish to intervene and subsidize you have to set tomorrow’s midpoint to take account of these negative pressures. And then the day after that, and so on. Before you know it, CNY DOWN. Not just down, but CNY DOWN every three months as those batches of “contingent liabilities” keep coming due.

Either you pony up more of them, to add more to your off-balance sheet war chest at the expense of future RMB, or you let them, and CNY, go.

That’s not the only problem in all this mess, either. If you are allowing FX to expire that doesn’t just mean the swaps disappear. You’ve borrowed contingent funding from the derivatives market and if you aren’t going to roll them over every three months you have to borrow some dollars (or sell UST’s) to settle out – which adds a little (maybe a lot) more onto demand for dollar funding.

Just like 2015, as CNY plummets seemingly out of control the mainstream still unaware of how anything fundamentally works will try to explain all this as competitive devaluation. This time, we are being told, it is President Trump’s fault for trade wars. The Chinese are just manipulating their currency in response to that.

China is manipulating its currency, alright, but as a passenger on the eurodollar train. The fact that it keeps to a regular schedule doesn’t suggest control; quite the opposite.

Stay In Touch