December 16, 2015, was perhaps the perfect synopsis of Janet Yellen’s mercifully brief tenure. First Ben Bernanke and then Yellen had spent 2014 telling everyone the US economy was in more danger of overheating (best jobs market in decades, they said) and therefore not only would the FOMC taper and terminate QE there would be rate hikes to follow closely thereafter. Officials were itching to get ahead of the inflation pressures they kept seeing, particularly on the Chairman’s so-called labor market dashboard.

With real GDP up around 5% in two consecutive quarters in the middle of 2014, the idea spread that recovery, a real one, was finally at hand.

But 2014 instead ended under confusing circumstances, outwardly contradictory evidence piling up across markets that something wasn’t right. The oil crash and falling interest rates, both dismissed because, many believed, there was just no way Fed officials would fall for yet another false dawn (after the experience of 2011 and 2012).

The balance of 2015 was spent by policymakers in schizophrenia. Edging back and forth between “hawkishness” and “dovishness”, seemingly at random, August 2015 would deliver CNY and then a Wall Street mini-crash. What many had thought would be the beginning of monetary policy normalization by midyear, no later than September 2015, had been put on hold.

But why?

No one had any answer besides the generic appeal of “overseas turmoil.” As the year came to a close, the FOMC had only one chance left to deliver something. That was December 16. Under pressure to do more than just talk about positive things like normalizing rates, Yellen’s beleaguered group voted for the first rate hike in a decade.

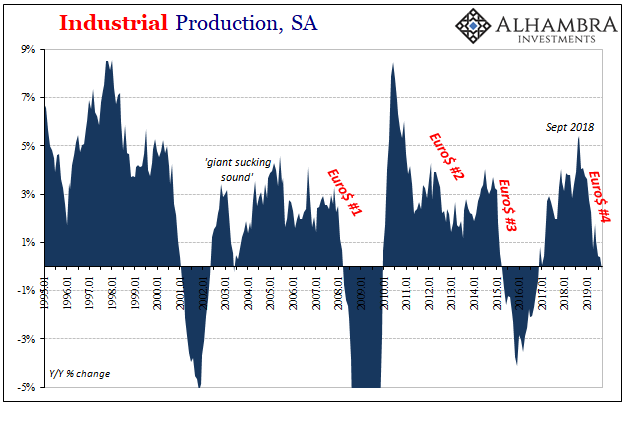

But on the very same day, the Federal Reserve also reported that US Industrial Production had declined for the first time since the Great “Recession.” IP has a very long history and rarely does it give false signals. A negative number in almost every case had preceded a recession declaration.

Thus, on the same day Yellen finally acted upon the widely held expectation the economy was recovering her central bank issued data suggesting it was instead close to, if not already in, contraction.

As I wrote up top, the perfect encapsulation of Yellen’s tortured, confused time as Chairman. On that specific day, I had written:

It is perhaps the perfect situational irony of this economic age, with the FOMC set to end its “emergency” policies by raising rates for the first time in a decade the very same day that the very same outfit, the Federal Reserve’s staff, just declared that the past cycle may have long since peaked. The monetary policy “exit” is a nod toward worries about the economy possibly overheating, meaning that the FOMC is considering a sprightful and fulfilling economic course at the same moment the institution declares the next recession may have already begun. You cannot make this up.

Yellen then spent nearly all of 2016 wondering which way was which. All the while, “overseas turmoil” raged and blew up a lot of other places.

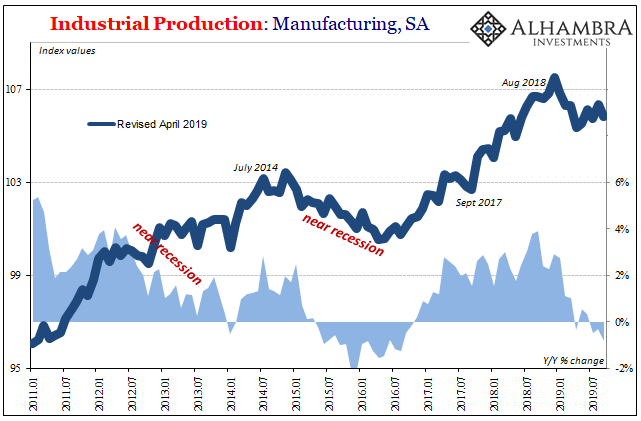

The US economy did not fall into outright recession – but it was so very close. And the scars of that near miss would be felt for a long time thereafter; in a labor market that has yet to really recovery, and especially around some Midwestern locales in November of 2016.

Even the New York Times, which had missed the significance of what IP was saying back then, two years too late finally admitted that something big really had happened. Calling it the Invisible Recession of 2016 in September 2018, it was only invisible if you had listened to Janet Yellen and those like her.

Sometimes the most important economic events announce themselves with huge front-page headlines, stock market collapses and frantic intervention by government officials.

Other times, a hard-to-explain confluence of forces has enormous economic implications, yet comes and goes without most people even being aware of it.

In 2015 and 2016, the United States experienced the second type of event.

There was a sharp slowdown in business investment, caused by an interrelated weakening in emerging markets, a drop in the price of oil and other commodities, and a run-up in the value of the dollar.

Those that the author writes in as causes for this invisible (to the mainstream) recession are actually themselves symptoms. All symptoms of the same cause – the third outbreak of what is a chronic global dollar shortage. But since neither Janet Yellen nor anyone else pays much attention to actual monetary conditions, that’s why it appeared to be “a hard-to-explain confluence of forces.”

It really wasn’t all that hard to explain.

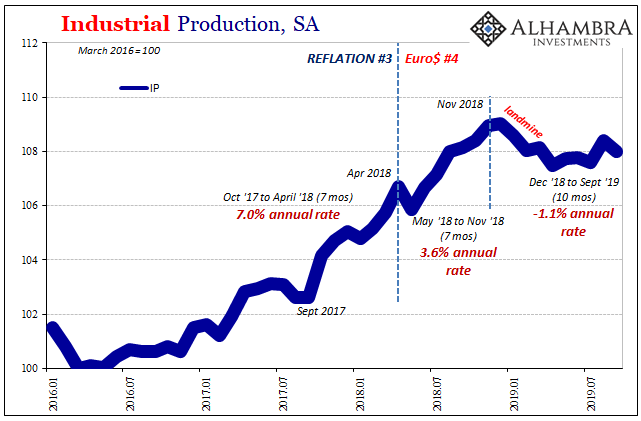

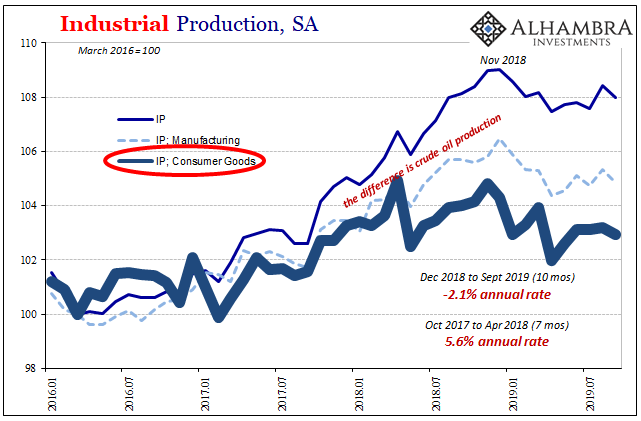

Why bring this up now? Because for the first time since then the Federal Reserve reports that US IP is once more contracting. Not by a huge amount, only -0.1% year-over-year in September 2019. Even so, it is another in a growing list of indications suggesting that the US economy like in 2015 is not fine.

While the data isn’t like German Industrial Production, it is of the same spectrum. And like Germany’s unending struggles, it’s not trade wars, either. It is a globally synchronized downturn which until more recently had been around the fringes of the US economy. No more. It is becoming more serious, and, as noted yesterday, seemingly doing so right on schedule.

Whether or not that means the US experiences a full-scale recession in 2020 may not ultimately matter; it may be just semantics. The reason is that like 2015 and 2016 the US economy still has yet to recover from the last one. That’s what Euro$ #3 ultimately represented, more proof that there are only false dawns like the one that fooled Yellen (and the one before that which fooled Bernanke).

Therefore, if there is serious fallout from Euro$ #4 in the US, and IP suggests that much already, what does that mean about another false dawn in what is now a clear string of them? It means there is no upside given whatever the downside may end up being.

In other words, more proof of the worst case. A recession is not that; being persistently unable to recover from what was called one more than a decade ago certainly is.

Until the “hard-to-explain confluence of forces” becomes easy to explain, this is what we will be stuck with. That’s the data dependent view, especially in light of this new data. It’s also why the “bond market” keeps expecting more rate cuts. Not that they’ll help, but that before too long even Powell will have no choice but to do something he doesn’t want to. The uniform experience of all 21st century Fed Chairs.

Stay In Touch