There’s a couple of different ways that Unit Labor Costs can rise. Or even surge. The first is the good way, the one we all want to see because it is consistent with the idea of an economy that is actually booming. If workers have become truly scarce as macro forces sustain actual growth such that all labor market slack is absorbed, then businesses have to compete for them bidding up the price of marginal labor.

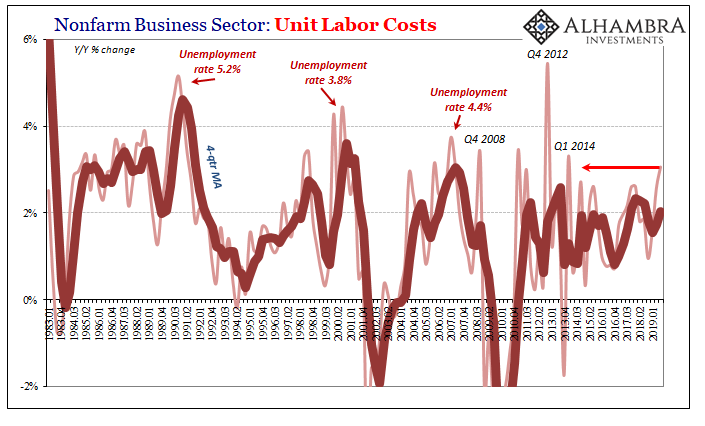

This is, of course, the exact scenario we’ve been constantly hearing about ever since the middle of 2017. Even for several years before then, all the way back to 2015, the unemployment rate had recovered to low enough levels Economists thought was around the right area for this mythical full employment threshold.

But because there was very little about 2015 and 2016 to suggest anything like that, it was left for 2017 before the LABOR SHORTAGE!!! hysteria could take over. And the only reason it did was because by then the unemployment rate had fallen so low that it left only two choices, as I wrote at the time:

It really is a binary option at this point: admit the unemployment rate is faulty and open the can of worms about the last ten years, or keep the faith as [Janet Yellen] has done all along and bet it all on an imminent surge in something.

They would bet on the surge, and for the next several years kept saying that wages were about to explode, therefore inflation, simply because authorities had no answers for the other option (the lack of recovery). At some point, they said, wages would have to.

According to the BLS’s latest productivity figures released this week, they have. A little. It wasn’t a full-on explosion, but Unit Labor Costs rose during the third quarter of 2019 by the most in five years. Finally, the boom?

Hang on. There’s another possible explanation for why Unit Labor Costs might jump. It’s the bad one.

If you look on the chart above, you’ll see that this measure of worker expense surged in the fourth quarter of 2008, too. That seems odd at first glance, after all you will never associate the aftermath of Lehman and AIG, the stock market crash and the implementation of ZIRP, with a healthy economy’s too much demand for a lack of sufficient workers.

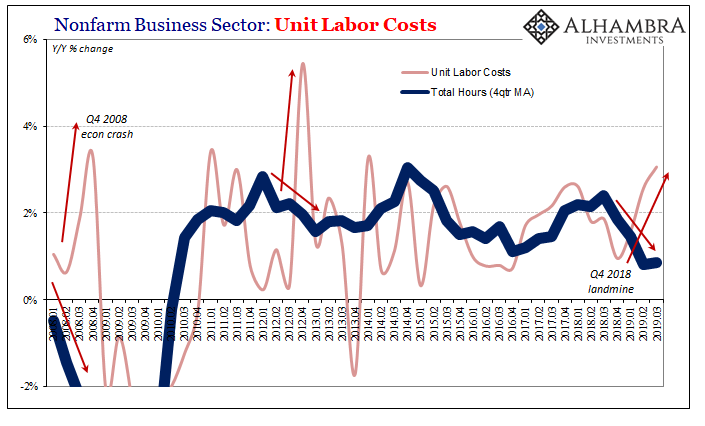

We explain it instead by what Unit Labor Costs actually are – the amount of cash businesses lay out for the amount of work workers put in. Therefore, if those business owners suddenly see the economy turn downward but haven’t yet adjusted their worker rolls to the reverse, the Unit Labor Cost will rise. Fewer hours spread among the same workforce payrolls.

That’s just what it was in Q4 2008. Even though by then layoffs were deep, they weren’t deep enough. By Q1 2009, American employers did what they always do when the bad jump in Unit Labor Costs shows up – they cut their payrolls at an even greater rate than the slack in hours in order to better match labor utilization with crashing economic demand.

As bad as mass layoffs had been in late 2008, they would get even worse to begin 2009.

The key is hours as a proxy for macro level demand. If hours are declining or even just decelerating more than payroll growth is slowing down, then Unit Labor Costs will jump. And that’s just what has been indicated since the fourth quarter of last year (the landmine).

Hours Worked, according to the BLS, have slowed to the lowest since 2010, on average, while the level of payroll growth has come down, too, but not enough apparently to hold the line on costs. Therefore, the unit price of labor has accelerated this year.

And that suggests businesses are going to be more cautious about their workforce levels in the near and intermediate terms. We’ve already seen a sharp slowdown in employment growth throughout 2019. This data, the bad jump in Unit Labor Costs, indicates that employers haven’t scaled back hiring by nearly enough.

Sorry Jay Powell. Another key piece of data against the “strong” labor market.

The question is whether employers make even bigger negative adjustments moving forward. Because that’s the recession – especially when it becomes self-reinforcing (businesses cut workers, who cut spending, leaving businesses to further adjust to further falling revenues by cutting even more workers).

As we’ve said all throughout this year, there hasn’t been a recession in the data. But the recession risks remain all over it.

Stay In Touch