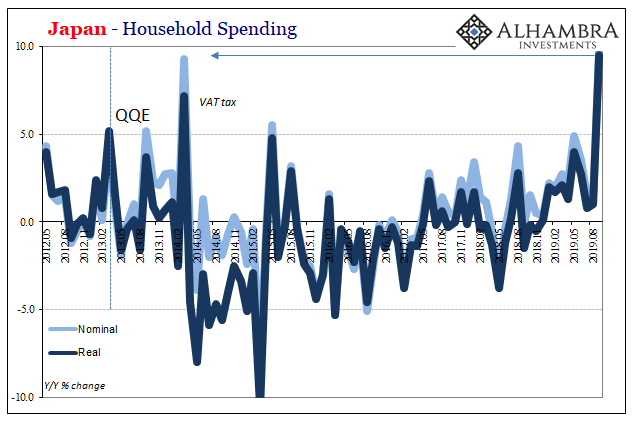

Earlier this month, the Statistics Bureau of Japan had reported an enormous surge in household outlays. For the month of September 2019, the Japanese had splurged on everything from big ticket items to regular discretionary products. Total spending in the month was up 9.5% year-over-year in real terms, an enormous increase which had been the fastest pace ever recorded in data that dates back more than half a century.

The reason for the increase was simple: the looming VAT tax hike. In September, the Japanese people rushed to buy whatever they could before the price increases took effect on October 1.

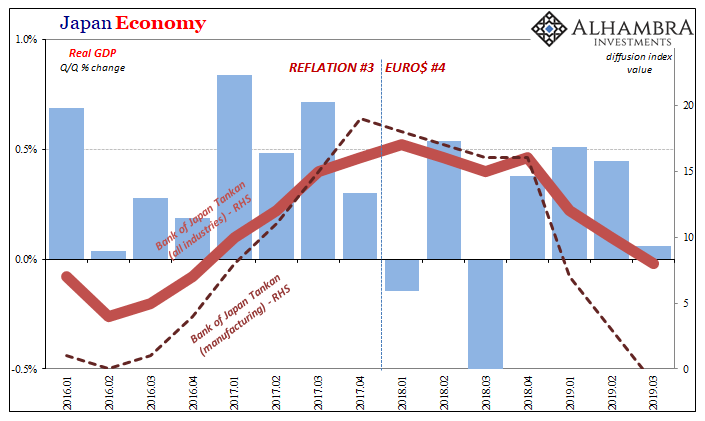

For many, it seemed a relatively good sign of economic strength reinforcing recent economic data. After a very rough start to 2018, two negative quarters of GDP out of the first three, Japan’s economy had appeared to stabilize while the rest of the world fretted weak global growth. Even though the export sector in 2019 began to subtract once again from the nation’s economy fortunes, buoyed by internal consumption GDP stayed constant in the first two quarters of this year.

There have been growing signs of trouble, though, which have defied conventional proprieties particularly relating to how we are supposed to factor time. It doesn’t seem like Japan or any economy (like, say, Germany’s) should be held back continuously if unevenly. We are taught that an economy is either booming or in recession.

When it had appeared Japan had avoided one, or the so-called technical definition of recession, late in 2018, the matter was believed settled. Last year was an “unexpected” deviation in course and given enough distance the Japanese system would soon find its way back toward the recovery officials have been promising forever.

Recent data, however, has begun to suggest that Japan may not have avoided anything. The bumpiness of 2018 has been followed by further problems in 2019; not recession, not yet, but more instability beyond just the external sector.

And that raises substantial questions about September’s household spending. A sign of strong Japanese consumers, or a stark demonstration of just how bleak things have become? Again.

We’ve seen this all before – five and a half years ago. Japanese officials took the word of Haruhiko Kuroda’s Bank of Japan about how QQE, begun in 2013, was unfolding entering 2014. Strong economy, Kuroda said, and Abe’s government believed it. The VAT tax was raised in April 2014, creating a massive surge in household spending the month before.

Economists were encouraged then. At the time, I wrote instead:

If a changing tax rate forces consumers to consume at such a high level, that would suggest that household expectations are not overly rosy further on. If the economy were truly set to recover, the tax rate would not have pulled forward so much demand. It really is telling that the shopping spree to save some tax money was so engrossing and comprehensive.

A recovery-confident consumer cohort isn’t going to dip quite far into savings for a relatively small increase in prices. The fact that the Japanese did was a worrisome sign that they weren’t at all optimistic about how the economy was going to look that year and beyond.

And they were right, as even Kuroda conceded by October 2014 (increasing QQE after spending a year and a half telling everyone around the world how unquestionably powerful it was and would be).

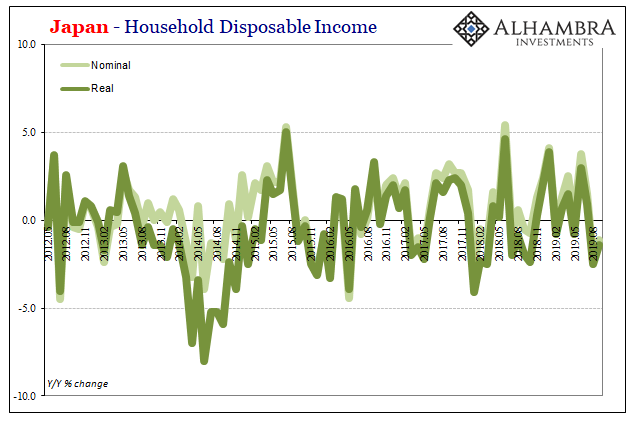

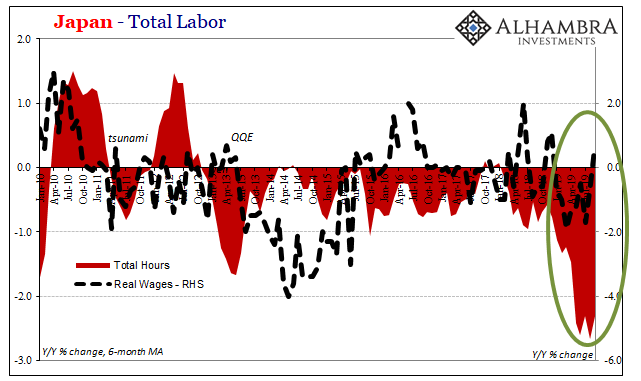

Japanese households appear to be signaling the same lack of confidence this time around; at a record spending rate, maybe even a little more forcefully still than five years ago. Given the way the labor market has behaved recently, that’s not really surprising. While household spending was way up, disposable income was down each of the past two months (August and September, the latest estimates). Japanese businesses are working their workers decidedly less of late, too.

In fact, Japan Inc. has grown noticeably pessimistic this year, meaning more than has become usual. According to the Bank of Japan’s Tankan economic survey, broad expectations for the economic climate are the lowest they’ve been since the bottom of Euro$ #3 in 2016. In the manufacturing sector, sentiment hasn’t been this low since 2012 and 2013 when QQE and Abenomics were first introduced.

Japan’s Cabinet Office added to the growing unease and uncertainty last week by reporting a third quarter GDP number that was basically unchanged. According to their latest calculations, output in Q3 increased by just 0.06% over Q2. What had seemed a relatively stable way out of 2018’s mess begins to look more like a continuation maybe even acceleration of it.

Time isn’t really the factor everyone thinks for Euro$ #4. What I wrote recently about Germany’s experience with it is merely confirmed by the same for Japan.

We are taught that an economy either booms or busts, no in-between. That’s just not true; there’s much more nuance to every situation. In terms of these eurodollar squeezes, what results especially in GDP is a clear change in the overall situation. Not flipping directly from growth to recession, rather an end to growth and the beginning of volatility and instability.

That’s the squeezing.

Haruhiko Kuroda even understands the risks, though after all this time and constant failure he still can’t figure out why. Unlike 2014, central bankers at the Bank of Japan have been far more cautious especially as 2019 lingers under suspicion of weakening global growth. There’s much more appreciation at least in later 2019 as to how much of a negative effect retreating global growth really can have.

Knowing full well Japanese households went nuts in September, Kuroda left no doubt about what’s ahead for BoJ. It isn’t going to be an end to QQE, rate hikes, and normalization via actual, booming recovery. No, he promised yet more of the same at the last policy meeting:

Our new forward guidance is aimed at clarifying our stance that our policy approach is leaning towards additional monetary easing.

That’s ultimately the point he and everyone else keeps on missing. Monetary policy is whatever it is, whatever form it might take (I keep saying they should start buying up the clouds passing over the islands or the ocean water surrounding them, it wouldn’t make any difference), but whether it becomes “easing” is entirely out of the central bank’s hands.

It is the eurodollar’s world; we are all just trying to live here.

Stay In Touch