Back at the end of April, the FOMC and its dozens of staff members gathered around to talk policy as those people always do every six weeks or so. The agenda was quite full, with Jay Powell having had to switch from rate hikes to a Fed “pause” the few months before and none of them really sure why. Economic weakness had appeared “unexpectedly” (they never pay attention to the dollar) and along with it inflation rates began to stumble, too.

Many participants viewed the recent dip in PCE inflation as likely to be transitory, and participants generally anticipated that a patient approach to policy adjustments was likely to be consistent with sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the Committee’s symmetric 2 percent objective.

Chairman Powell already had one puzzle to deal with as far as consumer prices were concerned. You might remember 2018 for being the year of the unemployment rate. Quite simply, he wouldn’t shut up about it.

But even the boasting was supposed to signal a deeper change in economic condition, the economy finally breaking free of its post-crisis haze and out into inflationary acceleration. Powell’s bragging was, essentially, how QE and low interest rates had burned off all the “slack” left over from the Great “Recession” at long last.

All he needed to confirm his assumption (it was always just an assumption) was some convincing acceleration in consumer prices. You might also remember their logic: a tight labor market would leave companies to increasingly compete for increasingly scarce spare workers, driving up business costs that are then passed along to consumers in the form of the PCE Deflator running hot.

The FOMC even made a point of changing the language interpreting its inflation mandate under these circumstances. The Committee added the word “symmetric” to it; in other words, before 2018, given how long the economy had been working through its tremendous amount of slack, and therefore how long inflation had been unusually low, officials were going to let consumer prices rise to more than their 2% goal in order to make up for it.

The reason was expectations. That’s the other part of this whole thing. For policymakers, it is the major part and the one factor they obsess over most. Inflation expectations are everything to a central bank (where, you know, money used to be).

Symmetry in monetary policy was an attempt to address any possibility that inflation expectations might become “unanchored”, a central banker’s worst nightmare (which tells you just how much they worry about the wrong things). By coming out and saying, in May 2018, no less, how monetary policy wouldn’t clamp down at the first signs of the expected inflationary breakout it was supposed reaffirm the Fed’s dominance over the matter, and therefore all economic affairs.

But, as I wrote, Jay Powell already had a problem. It didn’t happen in late 2017. It didn’t happen at any point in 2018, either. Though central bank officials were quick to remind everyone of the unemployment rate, there wasn’t even much acceleration in wages let alone consumer prices.

For all the talk of an inflationary breakout, what stood out was the lack of inflation at the time as well as looking ahead.

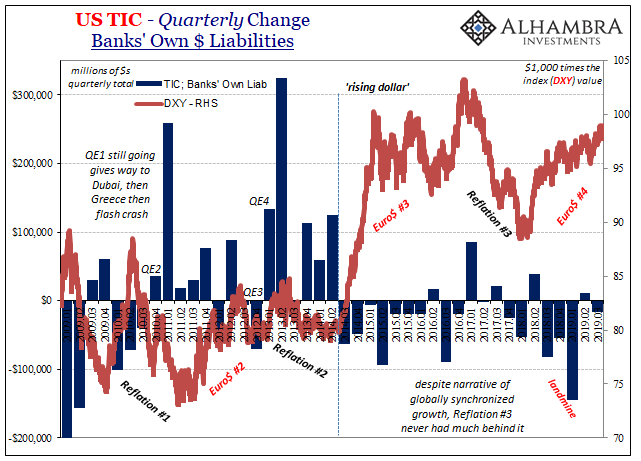

I’ve written (too) many times that Reflation #3, globally synchronized growth as it was called, had been nothing more than a bumper sticker slogan. In a lot of ways, across way too much of the data, it was incredibly underwhelming.

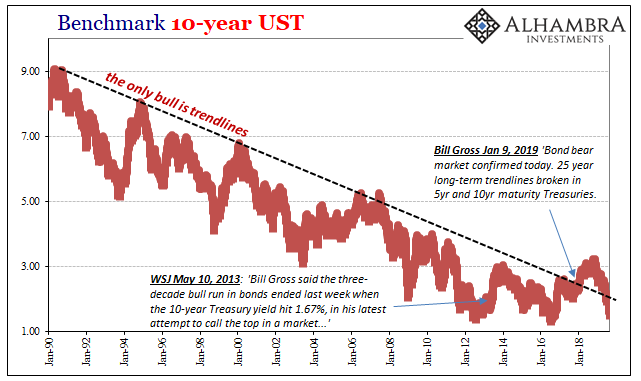

This was the primary reason why I referred to late 2017 as inflation hysteria: like most hysterias, there was little to no basis in fact. While central bankers the world over kept assuring everyone it was real, the bond market, where real monetary policy is made, shrugged.

A big part of the reason was in how Euro$ #3 seems to have broken the very idea of recovery itself. While Euro$ #2 was the last straw as far as the eurodollar system internally was concerned, the third episode was where it finally manifested in more outward ways.

The year 2014 turned out to be the crucial pivot, and you can see it in data and market histories from all over the world. From that point onward, there was no turning back – 2017 never really had a chance.

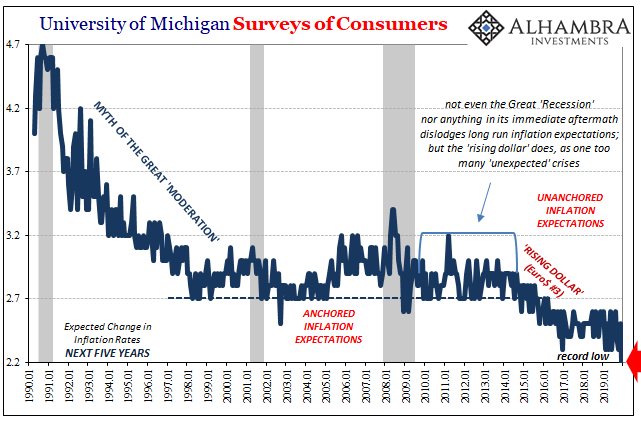

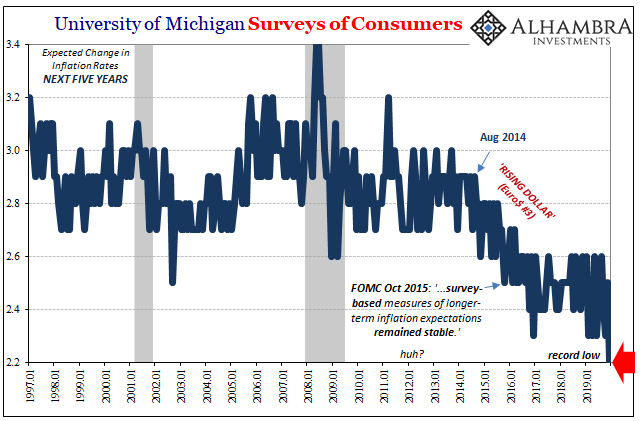

That was true in terms of inflation expectations, too. Fed officials were either in complete denial about it, or completely dishonest. Dating back to 2015, when the switch occurred, Janet Yellen did her best to deny it had happened even though it was so obvious that it had.

In October of that year, the FOMC minutes declared how “…survey-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations remained stable” when such a statement was demonstrably untrue.

Not just survey-based measures, either. Market-based measures of inflation expectations had tumbled, too, and beginning at exactly the same time: 2014.

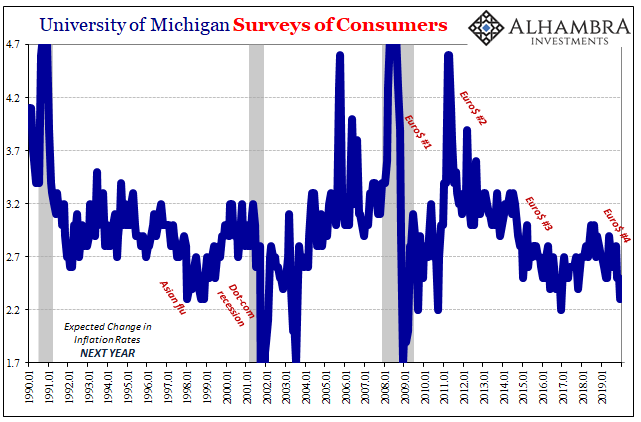

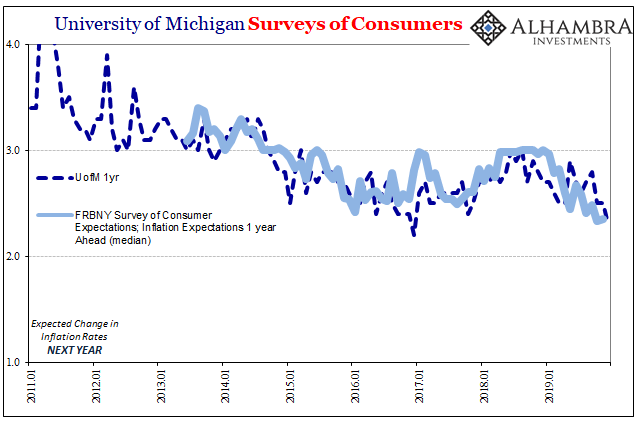

What’s missing on the charts above? Reflation #3. Globally synchronized growth as anything meaningful. In other words, despite the constant reassurance that it was real and powerful, becoming a full-blown hysteria by late 2017, consumers weren’t seeing it on the ground. Even the short-term measures of expectations suggested how disappointing it had really been.

The reason inflation expectations matter so much to central bankers is credibility. In a money-based regime you don’t really need credibility because you have all the money. Simple. Neat. But in an expectations-based regime, the one predicated on not being able to define money, which is how central banks have exclusively operated since the eighties, it all comes down to that one characteristic.

Officials really believe that if inflation expectations remain anchored in an area that’s consistent with how they conduct themselves and attend to their mandates, those anchored expectations confirm in economic terms how the public must generally be content with monetary policy because the public believes firmly in the central bank’s ability to conduct it.

Falling inflation expectations, especially should they become unanchored, is the public expressing widespread, serious doubt.

Can you blame most people? Especially after the twin hyping of first 2014 and then 2017 when what followed them was first 2015 (and a near recession) and then 2018 (the start of the next downturn which lingered a full year into all of 2019). As you can see on the charts above, inflation expectations have tumbled – again.

In the UofM’s surveys of consumers, long-term expectations hit a record low in December 2019 – the latest data. It’s the long run where the “anchoring” is most expressed.

But it’s not just one survey or another, it is consistent across all the surveys. We can take the UofM’s inflation expectation data and match it with the Fed’s version of the same (FRBNY conducts broad surveys of several consumer factors, including inflation expectations). Damn near perfect match.

What you don’t see on the chart is much of Reflation #3, but what you do see is how everything changed with Euro$ #3 (and what Euro$ #4 is doing on top of it). Inflation expectations continue to trend downward – not in a straight line, following closely the eurodollar system’s ebbs and flows – because despite all the talk of the booming economy, consumers like the bond market just aren’t figuring one.

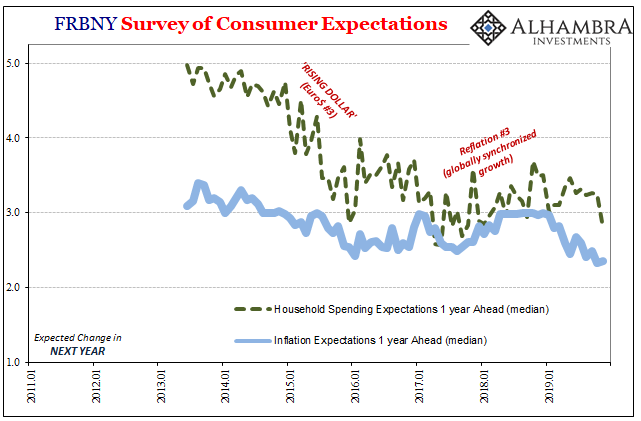

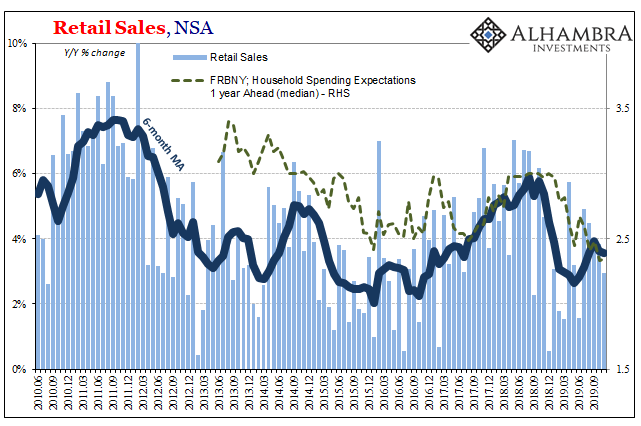

FRBNY’s survey also contains more bad news for policymakers at the end of 2019: expectations for household spending.

These, too, seem to have become unanchored by Euro$ #3, also importantly (And permanently) depressed by 2014’s false dawn that came from it.

The proverbial boiling frog doesn’t realize what has happened. The unemployment rate says the economy is booming, and so everyone says the word boom out loud and nods along in agreement with Jay Powell all the while expectations, along with bond market, show how deep down they don’t really believe it.

In a word: Japanification.

The public is becoming desensitized to this lack of real economic growth. That’s what is depressing inflation expectations. People tune out the talk of “stimulus” or “rate cuts” realizing instead this is what it is – and there is nothing the Fed or any central bank can do about it, not that they won’t continuously try.

In fact, quite reasonably, I will add, the constant QE’s only reinforce the more subtle understanding of where everything truly stands. The central bank is not central.

Thus, when confronted with this latest eurodollar episode, number four, it was pretty much expected (at least as far as how it affects conditions in consumer prices and therefore inflation expectations) if not perfectly expressed. The public intuitively feels, and tells survey gatherers, that this is just how it is. There is very little upside; the boom doesn’t really boom.

Economic slack, this no-growth world (Xi Jinping called it two years ago) is now expected to be permanent. Not just in China or Europe; here, too.

What we are witnessing in inflation expectations (along with bond yields around the world) is acceptance. Japanification wasn’t really about zombie banks and debt loads, it was the lack of answers leaving everyone no solutions with any realistic chance of success. Repeated QE’s simply have the effect, their only real effect, of hardening these sinking expectations.

Those already tell us that what in all probability will follow Euro$ #4 isn’t going to be recovery, either. What will come next in all likelihood will be just the next reflation in the string, Reflation #4 and nothing more. And the public will be equally unimpressed by it, expecting it already today to be underwhelming no matter how much hype Powell, Lagarde, Kuroda, etc., will predictably heap onto it.

And expectations also tell us policymakers will still have to contend with Euro$ #4 first. That’s in all the expectations numbers, too, suggesting like a lot of other data this one isn’t over.

Stay In Touch