What relaunched Europe’s QE four months ago was the word “protracted.” Central bankers love its opposite, the term “transitory”, which they use quite often at every sign of a weakening economy. To be fair, economies ebb and flow all the time and we don’t want policymakers to jump at every minor swing one way or another. The problem, it seems, is that they can’t tell which one it is.

Back on September 12, basically Mario Draghi’s final act as head of Europe’s Central Bank was to acknowledge that what he and everyone thought were transitory factors temporarily interfering with Europe’s economy had turned out instead to be “more protracted weakness.” Reluctantly, that meant more QE only this time around with tempered expectations.

“Now is the time for fiscal policy to take charge,” Draghi said. The ECB can’t solve all Europe’s problems, a much different message than last time. When it was launched the first in March 2015 the way he talked about it then was if there was nothing a good, well-executed large-scale asset purchase plan couldn’t accomplish.

While officials this time were downplaying both the need as well as the goals for it, Germany’s survey-takers couldn’t help but notice the love anyway. That country’s ZEW, in particular, has been like a rocket ship of optimism ever since the policy rerun.

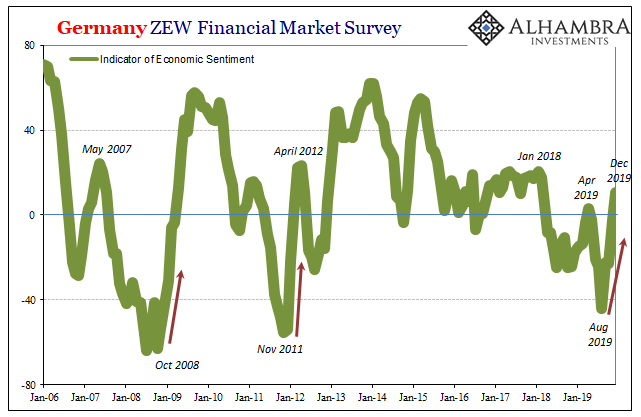

From a low of -44 reached in August 2019, the ZEW Indicator of Economic Sentiment had moved up more than 50 points by December. Standing at +10.7 in its last reading, it was only the second positive number of the year as well as the highest of them since February 2018.

Fitting in with the worst-is-behind-us narrative that has taken over in recent months, such a turn in positive sentiment would be a good start in that direction. After all, it was the ZEW which was among the first data series to point out that something was wrong all the way back in early 2018.

The problem with such measurements of sentiment is that you don’t really know what it is or why anyone is feeling more positive or negative. Back at the start of 2018, the growing pessimism proved to be based on a solid understanding of what was unfolding (no thanks to those like Mario Draghi who told them to ignore the “transitory” weakness which has now lasted just about two years and counting).

As you can see on the chart above, these German panels do love their “stimulus” – even when it doesn’t make much difference.

The ZEW’s sentiment index had bottomed out in November 2011, for example, and then surged over the next several months starting in December 2011 when the ECB (and Mario Draghi new to the job) announced a “flood” of “liquidity” in the form of LTRO’s. Quite massive stuff, officials said, and survey respondents were clearly enthused by it as they told the ZEW.

Yet, Europe would fall into and remain in recession for almost a year and a half past that bottom in sentiment. The good feelings were way too premature.

As they had been in late 2008. Three years before, same thing. October 2008 saw the first global panic in four generations and yet, according to the German businessmen talking to the ZEW, they began to turn more optimistic in November 2008 as two things happened simultaneously: first, central banks coordinated massive responses; second, the world economy melted down anyway.

Somehow the optimism prevailed regardless – at least in the ZEW’s sentiment estimates.

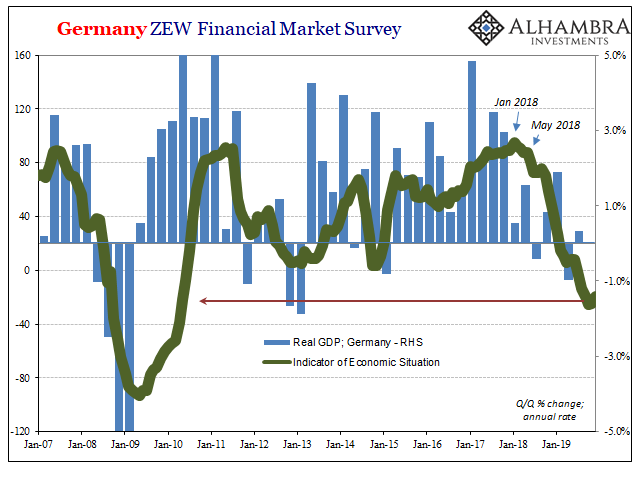

In 2008-09 as well as 2011-13, such stimulus-based positive sentiment got way ahead of itself. Looking forward, the ZEW said quite a few in German business were thinking things would change because of, largely, the ECB. But when asked about how things were right then, they didn’t have much positive to indicate.

That dichotomy lasted for a long time each time, even though in both the net overall condition remained a sharp recession. Survey respondents kept expecting big things from central bank activities even though it was clear they weren’t of much immediate (or intermediate) help.

September 12 was four months ago, three months now of data, and it hasn’t yet made much difference in the figures despite its imprint upon sentiment. Some Germans may be looking at relaunched QE and thinking it will make a difference, but they aren’t yet seeing it.

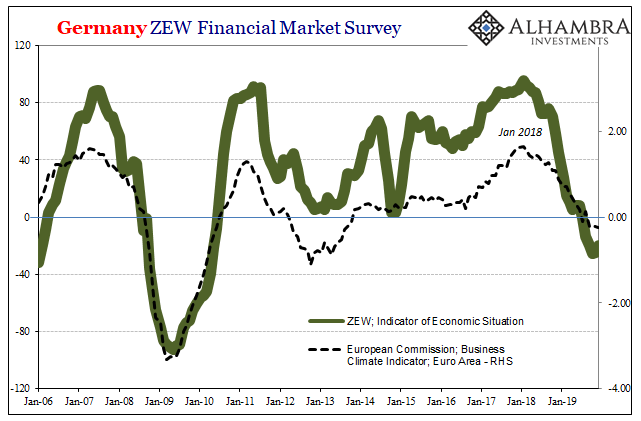

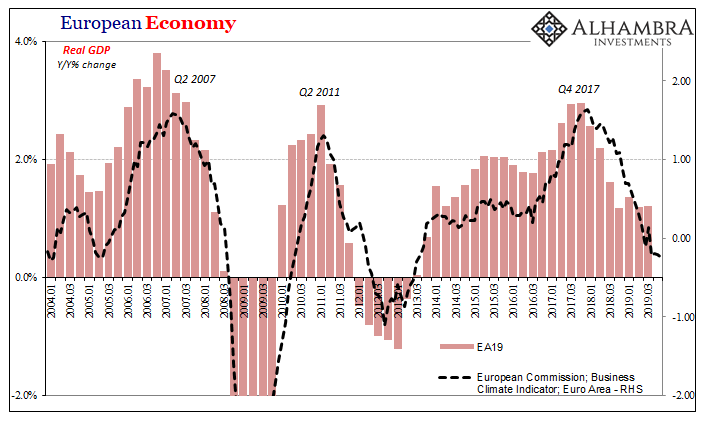

Whatever may be the cumulative feelings about Europe’s situation as it relates to Mario Draghi’s final act, the situation hasn’t changed. Whether we look at it from the standpoint of survey results, the ZEW’s like the European Commission’s Business Climate Indicator (BCI), or hard data, we have to question the positive sentiment surrounding QE and “stimulus” more generally.

Neither of those situational survey numbers (above) have picked up much change since September. It continues to deteriorate – not crash, rather the same slow strangulation that was supposed to have been “transitory” but now puts new economic meaning into the term “protracted.” The EC’s BCI lines up pretty well with European GDP.

That’s a bigger problem because, for one, many of those thinking Europe’s QE wasn’t needed were thinking that way since they believed it was mainly Germany (and Italy, only the two largest European economies) which had been struggling. So, transitory plus Germany’s isolation was for Europe supposed to add up to little more than an idiosyncratic nuisance.

Instead, the situational data, as well as the hard data, continues to show it’s the other way around. As Germany keeps on falling, failing ever to find a rebound point, it continuously exerts serious negative pressures on Europe as a whole. The Continental economy is following the Germans (not German sentiment) rather than having been insulated from whatever limited national factors they were supposed to have been.

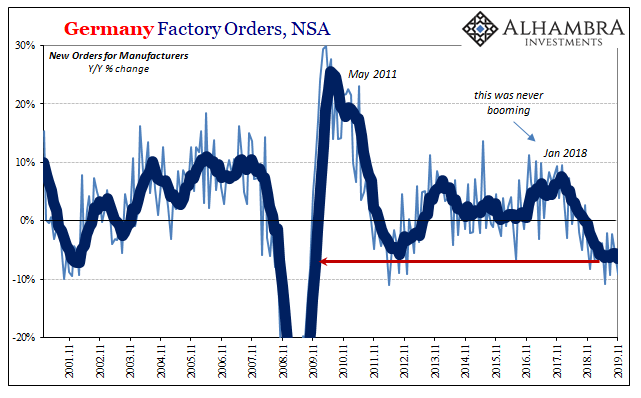

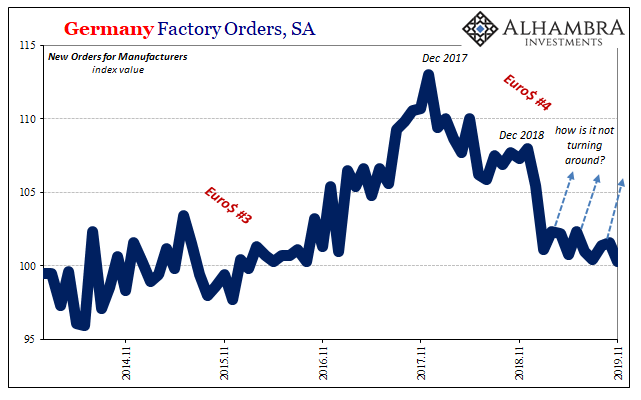

As for the hard data in leading Germany, it continues to confound the optimists. This thing of theirs has gone on for now just about two years. A manufacturing dip that turned recession a long time ago and still it goes down and down. The latest numbers from the manufacturing sector, factory orders, are shattering all expectations.

Not in a good way.

According to the German government, deStatis, factory orders for the country’s production dropped by 9.1% year-over-year (unadjusted) in November 2019. Rather than turning upward, it was the third time in the last six months with a contraction greater than 9% – a level beyond the bottom of Europe’s last declared recession in 2012-13. The 6-month average is down, not up, down to -6.5% which is the worst since November of 2009.

That’s a protracted slump.

Seasonally adjusted, factory orders two months ago were as low as they had been in May 2016, lower than in almost every month of 2015.

It is a pretty clear progression. It began in Germany’s factories right at the start of 2018 and from there it has spread. Dismissed the entire time as nothing, a minor and transitory annoyance, it has grown and grown into what is now a globally synchronized downturn with an as-yet unknown bottom.

European QE accomplished its goal, as narrowly constructed. QE is always and everywhere about sentiment and nothing more. It doesn’t print money, doesn’t add more liquidity to any system, it only makes people think the central bank is helping (though most people, even otherwise savvy German businesspeople, couldn’t answer you if asked in what way or how).

With Germany still struggling mightily, it doesn’t reflect well on the worst-is-behind-us narrative. If the leading stuff continues downward then either something substantial (in other words, more than sentiment) has changed to make it no longer leading, or the direction and trend remains.

Protracted is the word.

Stay In Touch