Why haven’t US Treasury yields exploded higher? Sure, they are, at the long end, up from their lows set in late August when the rate for the 30-year long bond reached all the way down to a new record. The winds of sentiment have shifted, benefited by globally coordinated (not quite synchronized) monetary “stimulus” as well as a healthy dose of trade deal positivity. All leading many, especially those in official circles, which include practically all of the financial media, to confidently (and ceaselessly) declare the worst is behind us.

And yet, the benchmark 10-year UST is just 30 bps above its 2019 low and the 30-year bond yield not even that much.

We have to suspect that something else is going on, and since we do our chief suspect remains the repo market. One of the primary sources, if not the primary source, at times, of demand for just these securities is as collateral for use in that place.

Hold up, you say, but didn’t Jay Powell fix repo?

That’s another nugget of convention that goes along with the idea of a global economy on its way back up. Sure, the Federal Reserve engaged in all kinds of interventions mostly beyond the normal scope of monetary policy and therefore quite purposefully beyond the grasp of most (including the so-called experts). For all anyone knows, the central bank just printed some more money and gave it to the repo market.

The fact that repo hasn’t shown up on the front page of Washington Post again or (incorrect) stories about it shared all over social media appears to be confirmation of Chairman Powell’s great monetary acumen. Something happened in September, a whole lot of people fretted about it, but they no longer do.

Case closed.

Yet, here we are with the bond market rather curiously stuck in a relatively narrow range still nearer the most recent nominal trough. For most, repo is a complete mystery. For others a little more familiar, it is a funding market. For a very few, a wholesale one.

What that actually and effectively means is a lot more than you might think, certainly way beyond anything you’ve ever been taught and told. To appreciate the full weight and implications of any of those distinctions requires looking at it from all angles. All the “experts” including those at the Fed only factor half of it; less than half, really.

Repo has always been explained from the perspective of bank reserves, which aren’t even a half. These are, as noted here, just the smaller public part of the cash side (private reserves the other bigger part) and play no part on the collateral side. Even the Fed’s repo interventions undertaken since September do nothing directly for this marketplace (they raise the level of public reserves available to primary dealers with the hope dealers then do something in repo with them without any regard to private reserves let alone any collateral).

Cash is interesting and important but nowhere near as interesting or often as important as collateral. Cash you can kind of understand. Collateral takes you in bizarre and counterintuitive directions like this:

Buried way down in a blurb and accompanying table on page 121 of the notes, even the most sophisticated of stock investors will have trouble understanding what’s going on here. For the layperson, forget it. How about regulators? Put a pin in that one.

Morgan Stanley is laying out for you the parameters of its rehypothecation program(s). The amounts are not small. According to the published end-of-year [2018] numbers, the bank reported $639.6 billion in “collateral received with the right to sell or repledge”, of which $488.0 billion actually was sold or repledged at that moment.

Half a trillion slightly visible of collateral repledged by just the one bank in the one small section where it has to disclose only what it has to disclose. To whom or for what purposes? I’ve been poking around in these places for two decades and I still struggle to explain it (as you may have noticed).

It reminds me somewhat of the division(s) between Newtonian and quantum physics. The rules and intuitive paradigm that lay out the rules for the former break down substantially when trying to understand and work out the latter. So it is with repo; the cash side is relatively straightforward, something akin to what you’ve been taught in Economics or Finance classes.

And what Jay Powell thinks he’s doing.

Jump over to collateral, though, and it’s a brave, strange new world. The very ideas and ideals of capitalism break down completely. Ownership, title, all cast aside for the defining liquidity characteristics. Collateral can be its own quasi-currency.

My purpose here is not to delve any more deeply into these shadows, merely to point out the missing more than half of the story; how it might be that a repo breakdown might still be ongoing even as the rest of the world has gone back to sleep on the matter. The Fed did some stuff and, unsurprisingly, it was largely irrelevant for anything except assuaging public anguish (which was the whole point).

There is instead a whole lot of space for problems to fester regardless of how anyone may feel about “money printing.”

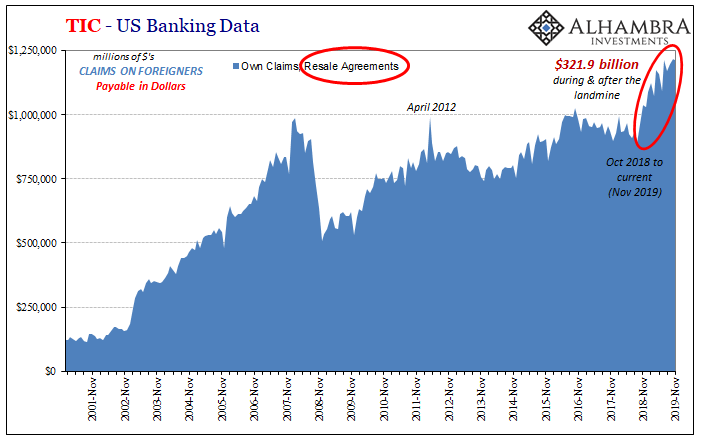

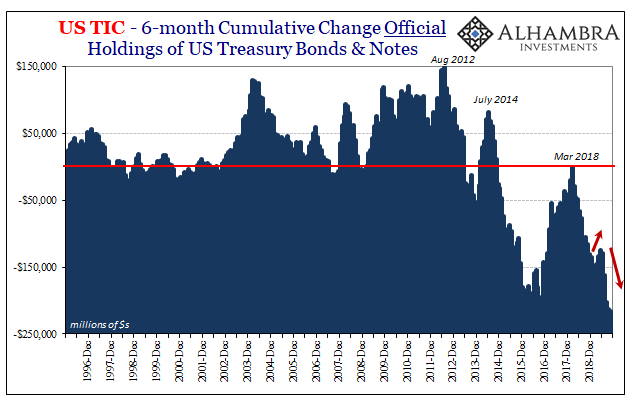

The good folks at the Treasury Department have updated their TIC figures through the end of November 2019. In them, as I’ve pointed out before, there are some line items drawn directly from bank call reports which are specifically dedicated to repo (in this case resales rather than repurchases; you can read about the distinction at the link above).

According to Treasury’s TIC report, US banks continue to lend (resales) to unknown overseas entities, in US$’s, via the repo market in a big way. As you can see above, ever since the end of September 2018, the landmine, the aggregate amount has increased by a mind-boggling $322 billion; an increase of 36% in only what’s been reported!

The level continues to rise even during the latest months.

That by itself doesn’t tell us much about collateral, though. All it says is that there must’ve been a huge shock, a surge in demand for funding and that US banks are the ones who had, to November 2019, stepped up and met it (not without dislocations and disruptions, obviously). This isn’t quite what some people had tried to claim (that whole thing about “too many” Treasuries and the foreign owners who allegedly only want to sell them).

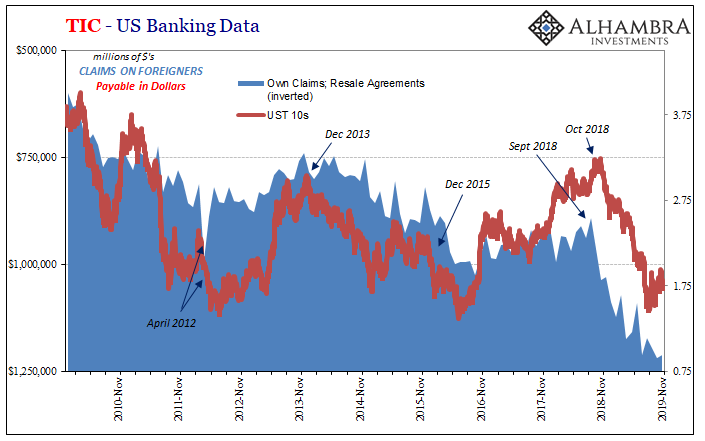

We only need to take one more step, though, to connect this demand for offshore repo with at least the price of the most pristine form of collateral:

It is amazing (not really) how the two line up so well; not perfectly, of course, but enough so as to build an undeniable correlation. When the demand for offshore repo rises (note: on the chart above the blue TIC data is inverted), a persistent and often confounding “conundrum” arises in the Treasury market as prices rise, too, therefore yields fall even and especially when it is said (over and over) they have nowhere to go but up.

Over the final three and four months of 2019 and the first several weeks of 2020, UST yields have been bombarded by positivity and positive developments. Through November, at least, the one thing missing is any substantial change as it relates to offshore repo demand.

I still believe, and the data continues to suggest in my interpretation of it, that it has something to do with a breakdown in collateral chains owing to revaluation of less-than-ideal collateral (global downturn would mean risks rise for the lowest qualities; the worse the possible destination of the downturn, the greater those perceived risks). One form has to be CLO’s (shown below) and the like, perhaps a glut of junk-ish EM corporates (which don’t show up in TIC and might not anywhere else, either).

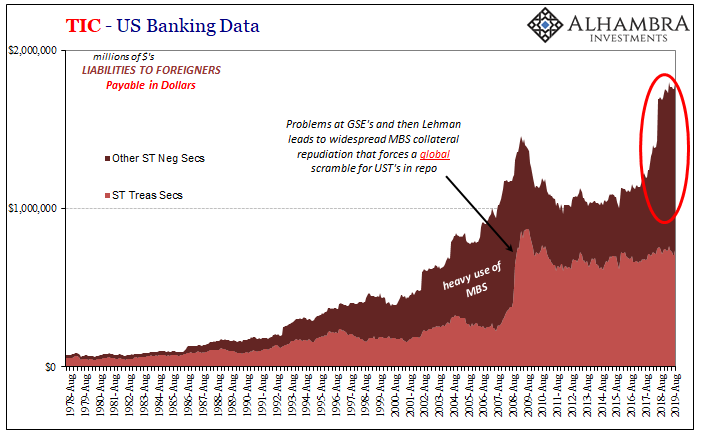

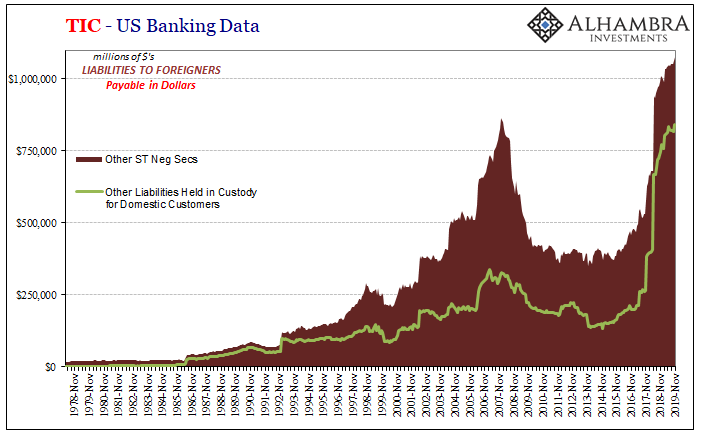

The TIC data continues to pile up repo demand (cash) from US banks (blue data) at the same time it displays how US banks owe foreigners (red data) ST securities of an unspecified type that are also the same as those being custodied by US banks on behalf of domestic customers who might be, and in my estimation probably are, foreign bank subsidiaries operating within the American border.

That’s a sentence that doesn’t make any sense – on the cash side of repo.

On the collateral side, there’s repledging galore which ultimately means – and this is the big thing – a dynamic multiplication factor.

Sometimes the re-pledged assets themselves get re-pledged, and re-pledged again. Only the one time for each bank that does this does it show up on financial statements, a partial disclosure buried in all the notes.

This is the collateral velocity, essentially the length of collateral chains. The longer they are, the more collateral has been re-pledged, the more fluid the repo system – on the collateral side. And that meant, at least before the crisis, plentiful monetary and funding resources for a whole lot of purposes, not all of them ended up as being wise.

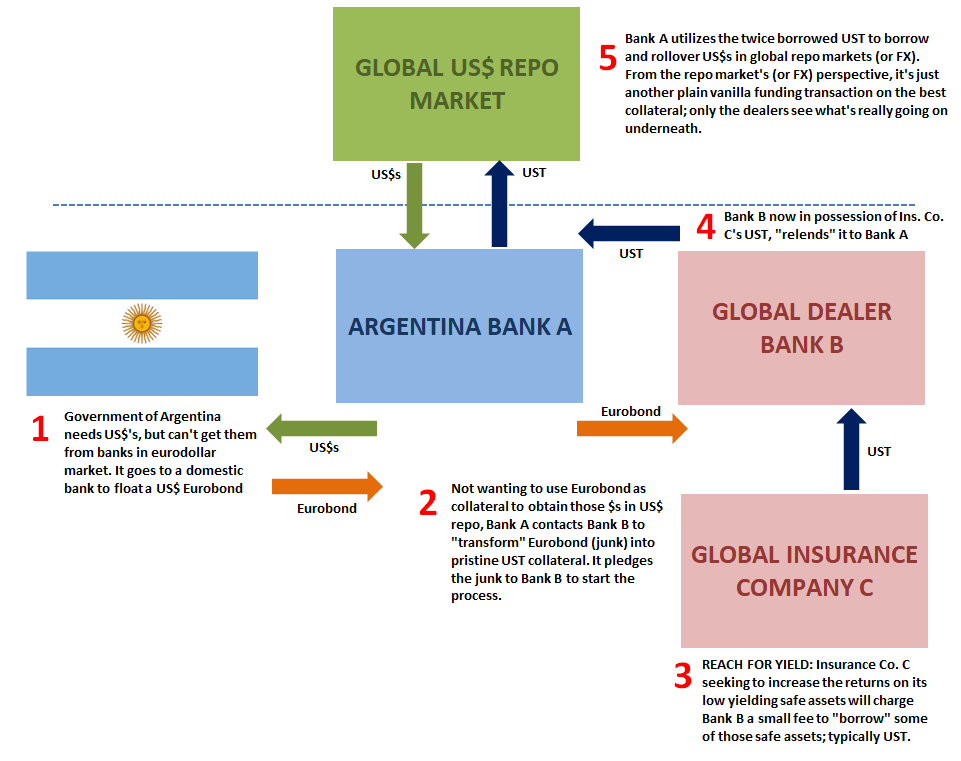

Let’s assume just for argument’s sake that a bank in Buenos Aires has been raising funds in the offshore repo market for its portfolio positions (credit assets) by transforming collateral with a dealer bank in Tokyo. The asset could be a CLO or, in the case of the example I used in the second edition of my Follow The Money series, an Argentine government Eurobond (a US$ denominated debt instrument floated in these offshore markets).

What happens if the Japanese dealer doesn’t like the look of the Argentine credit it has transformed into a UST for the first bank’s use in repo? The collateral chain shrinks a step which has the effect of placing the Argentine bank in a precarious position; in our simple example, which doesn’t explore all the kinds of repledging and rehypothecation behind the scenes, as the collateral chain shrinks the demand for UST’s must rise – somewhere.

There must be some other dealers out there who will accept the junk for transformation, but at a higher premium, those with the foresight (and inventory) to have stocked up so as to lend out as repledged “spare” Treasury collateral. The more that pristine form is demanded, the higher the demand for the securities and thus the higher the price of them (not just in terms of dealers’ risk adjusted spreads, either).

What the TIC data (again, through November, more than two months into the Fed’s “repo interventions”) shows is continued high demand for resales, meaning US$ repo market funding originating (on the cash side) at banks domiciled here. At the same time, the market prices an unusually persistent bid for the best US$ collateral.

There is, admittedly, quite a lot to the shadows in between those two things, especially as they may relate to collateral multiplicity of type and transaction, but as history has shown the correlation remains big picture robust for a reason. Despite the anti-hype, maybe the Fed hasn’t really done much for global repo – not that that should really surprise anyone.

Stay In Touch