Jay Powell says that three’s not a crowd, at least not for his rate cuts, but four would be. As usual, central bankers like him always hedge and say that “should conditions warrant” the FOMC will be more than happy to indulge (the NYSE). But what he means in his heart of hearts is that there probably won’t be any need.

Three should do the trick nicely.

And a lot of people, from what I can tell, believe him if not simply because he’s already stopped. The last two FOMC meetings have now passed without an additional rate action. If the economy was still under threat, Jay would have done something about it. The lack of further movement is comforting in its own way.

It’s part of the idea wherein the central bank’s default setting is thought to always remain on the dovish side. On the way up over the last few years, it was practice to skip a few meetings for rate hikes. Only three or four max per any calendar year.

When the time comes for aid, once the Fed gets going it stays going – unless there really isn’t any need for it to continue. This is the 1995 or 1998 scenario. Just a little bit of help to insure against some minor downside noise (though the Asian flu was hardly noise, it just didn’t impact the US as much with the eurodollars freely flowing onshore via housing and whatnot).

If this is convention, then Powell’s patience and confidence is itself a positive signal. Or some are saying.

But it isn’t convention. It sure wasn’t during the Great “Recession”, nor had it been in the aftermath of the dot-coms. In fact, each time there were significant breaks at times between rate cut actions.

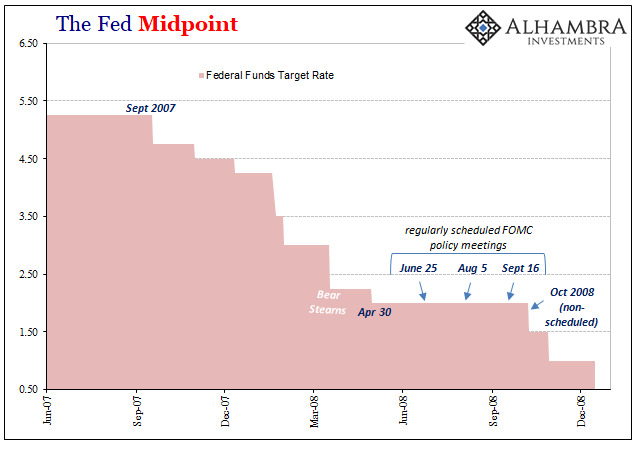

Ben Bernanke’s Fed had started down that reluctant road in September 2007. As usual, they were late to the game and only got going once it became obvious so much had been going wrong. Some things never change. In the case of 2007-08, it wasn’t just economic weakness it was also the sprawling, widespread monetary fire spreading all over the world (how could that have been, again?)

At one point in January 2008, Bernanke oversaw what he and his fellow policymakers thought was enormous “stimulus” – in the space of just ten days the federal funds target was reduced by a whopping 125 bps.

It, of course, had little effect. Within seven weeks Bear Stearns. But that is when officials started to feel more positively, as if with a lag those rate cuts along with other interventions (like TAF and overseas swaps) were turning the tide. The idea grew that late as they may have been policymakers really believed they had finally caught up and got ahead of the crisis. Bear would be their ultimate success (read the 2008 transcripts).

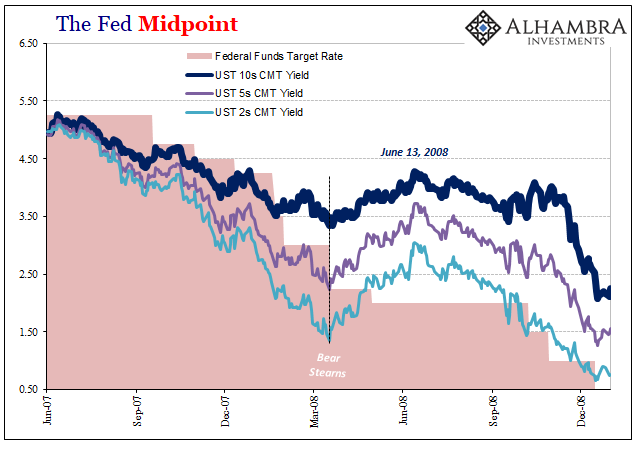

And they weren’t without some basis for the opinion. The bond market wondered if that was enough, too. Following Bear, yields backed up and for a time it did seem like there was at least some (slim) chance that the world had dodged a huge bullet.

Just to make sure there was one more rate cut at the end of April 2008 and that was what many thought should have been the end of it. The belief gained currency (pun intended) with a near continuous stream of confirmation for the optimistic case. GDP was actually positive in Q2, reported in July. Some economic numbers, not to mention inflation, suggested some possibility for a quick turnaround, maybe perhaps likely avoiding a recession altogether.

But, while the bond market turned pessimist again as early as mid-June, the Fed remained on hold over the next three scheduled FOMC meetings – including one that occurred just one day after Lehman. It was uncertain summer, to put it mildly.

For just about half a year, Bernanke had paused and said the world was looking better. It wasn’t getting better at all. The rate cuts were renewed early in October as all hell broke loose. It hadn’t been a small miss.

That’s really the point. And, to be perfectly clear, I’m not saying we are repeating 2008 in 2020. Not at all. What I’m trying to point out is that the Fed, whomever is leading it, is prone to just these kinds of errors.

And not just recession errors, but also errors over recovery and positivity. Take the 2001-03 case.

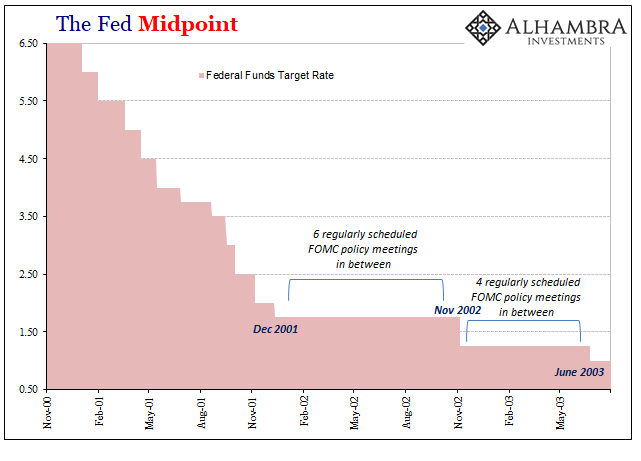

Alan Greenspan’s Fed began 2001 with a 50, and then didn’t stop for almost an entire year. By the time they were done, that December, the fed funds target had been scaled down from 6.5% to just 1.75% (and still the recession happened anyway; go figure). The events of September 11 were a very small part of it.

According to most statistics and later the NBER, this dot-com recession ended in November 2001. It was widely assumed that recovery would follow, commencing immediately. The typical V-shape.

Despite Greenspan’s assurances, it did not. Therefore, while the “maestro” stood pat for six regular policy meetings into 2002 he grew impatient as the economic data didn’t really improve all that much (something about a giant sucking sound).

There was a rate cut finally at the November 2002 meeting followed by four more in between without another even though the economy still failed to accelerate. The final fed funds reduction wouldn’t occur until June 2003.

In other words, infer nothing from the Fed’s actions. Powell may be satisfied, or he says he is, but history shows that a satisfied Fed Chairman in the middle of rate cut actions isn’t at all likely to remain that way. The reason is quite simple.

Monetary officials really have no idea what they are doing. For all the theater, the performance and visuals, the air of grandeur and highest orders of scholarship, they’re really just winging it. Every time.

Stay In Touch