The Federal Reserve added the word “symmetric” to its inflation goal for a reason. Back in May 2018 when it was made official officials made quite a big deal out of it. It was for two reasons, actually, both of them intertwined in the way Economists believe the economic system is supposed to work; and the central bank’s place in it.

First, even though there was still some inflation hysteria by then it was already waning. The dollar had turned around and nowadays even Economists have finally figured out a rising dollar is usually a bad (disinflationary) sign. To goose inflation expectations a little, the FOMC said that its inflation goal would be symmetric.

In other words, normally what happens – what is supposed to happen – is upon completion of economic recovery at the first sign of accelerating inflation the central bank acts to shut that down. It’s the whole point of rate hikes after recession. To cool the economy before it runs “too hot” (I know, I know).

The word “symmetric” was an acknowledgement that inflation and therefore the economy had underperformed for a very long time. So long, it had created a new meaning for the word “transitory” (it used to mean temporary but came to be, in this setting, a euphemism for Janet Yellen’s patented deer-in-the-headlights stare when confronted with economic downgrades and overseas turmoil, 2015’s version of “global disinflationary pressures”).

What the Fed was trying to convey to you, me, and everyone else in May 2018 was that it was changing with the times, sort of. The FOMC would not come rushing in to clamp down on inflation when it finally showed up. The monetary authority would let it run “hot” for quite some time in order to make up for how long it was cold.

Like a fast sprinter who stumbles out of the starting gate, they will have to run that much faster in order to catch up and then win the race. That’s what Jay Powell was saying about this new definition of his mandate. Since the economy had been so cold, they were going to be patient even when it got hot. Thus, the second reason for the change which was supposed to help the first reason of inflating inflation expectations.

If you believed the economy was about to go ballistic, what with the unemployment rate and all, and then you believed Jay Powell when he said “symmetric”, then, sure, inflation expectations were raised. Did anyone actually believe any of this, though? I mean truly, seriously believe?

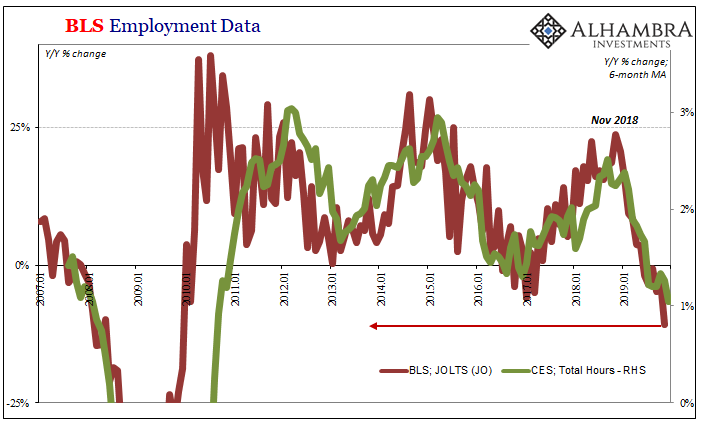

The talking heads sure did. The bond kings were all onboard. Other than those, the track record (shown below) was difficult to ignore. It’s even harder a year and a little more than a half later. And the unemployment rate today is even lower still.

When Powell and all the rest say inflation is going to pick up because they believe the economy is turning around, led in the right direction by the unemployment rate, even the once-uncritical media is having a very hard time seeing it.

From Bloomberg (!) on Thursday:

With the coronavirus outbreak threatening to disrupt the Chinese economy, concerns about the business cycle are undoubtedly a factor. But more important still are emerging doubts over the ability and commitment of policy makers to shore up growth and spur inflation.

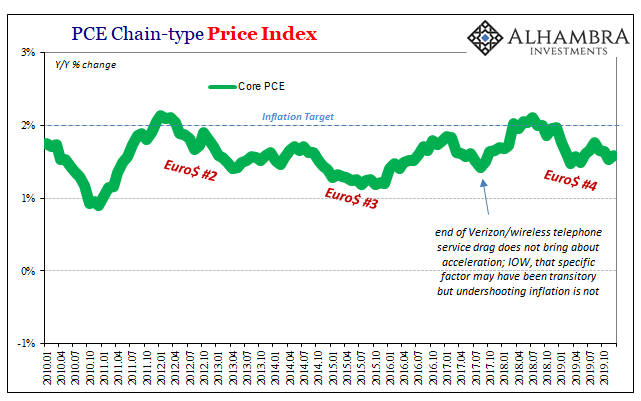

Forget overheating, where’s the slightest bit of warmth? The PCE Deflator (monthly) gained 1.61% year-over-year in December 2019. That was up from 1.40% in November, and the highest since December 2018.

Hardly evidence of anything but WTI. Oil prices had been rising up until recently, contributing the entire difference. Underneath energy, the so-called core inflation rate continues to show not one sign of acceleration.

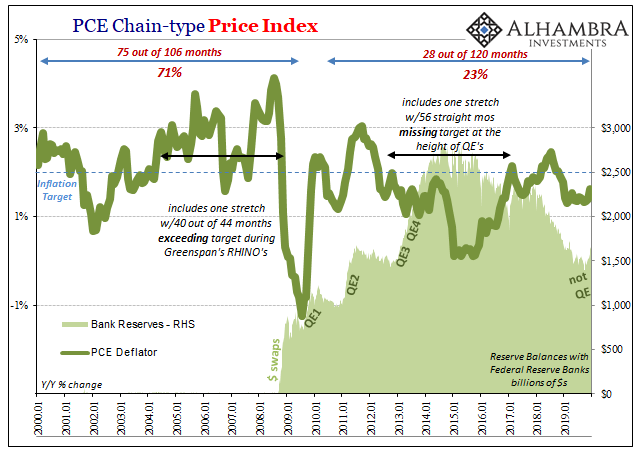

It’s actually remarkable how consistent inflation has been – even though monetary policies have been frightfully inconsistent. One QE, then two, a Twist, a couple more QE’s, then several years without, and now maybe kinda more QE again. And inflation is now what it was all that time. It’s as if monetary policy doesn’t factor, entirely detached from its second mandate.

Which only raises substantial questions about its first: full employment. What the inflation data (more than) suggests is slack. The core inflation rate is the same today as it was in 2011 or 2015. The unemployment rate had been much, much higher at those times – when slack was acknowledged.

The only thing that changed was the unemployment rate.

And that’s only where Powell’s big problems begin. He’s now got an entrenched Euro$ #4 to pour even more cold water on his barely lit inflation paradigm. This elongated, and elongating, monetary squeeze is definitely sucking the life out of the labor market. We’ve seen it in the headline payroll figures and then in other places like hours and job openings.

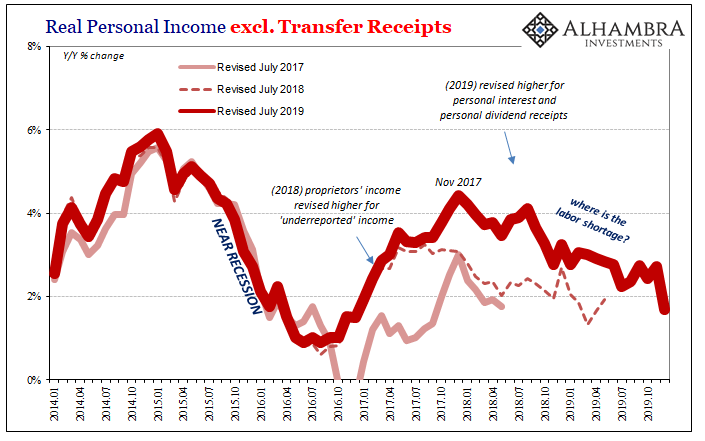

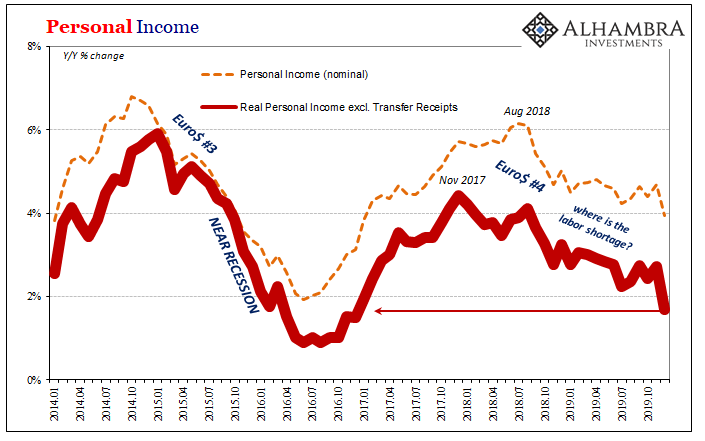

Now income estimates.

Nominal Personal Income growth was less than 4% year-over-year in December, the first time below that threshold since 2016 and Euro$ #3. In real terms, excluding transfer payments in order to isolate conditions in the private economy, December’s estimate was an extremely chilly 1.7%. As you can see above, that’s pretty much the same as the trough of that prior downturn – which had nearly led the US economy into recession.

Far from in a good place, there’s growing evidence the US economy is in the same place – as late 2015 early 2016. And a fair bit more evidence (more on that later) that Euro$ #4 unlike #3 probably is not yet finished with the economy.

Existing macro slack they spent years claiming had been cleared up plus now growing headwinds and disinflationary pressures. Liz McCormick at Bloomberg was right. Nervousness in January isn’t just about the coronavirus; if anything about the pandemic.

Stay In Touch