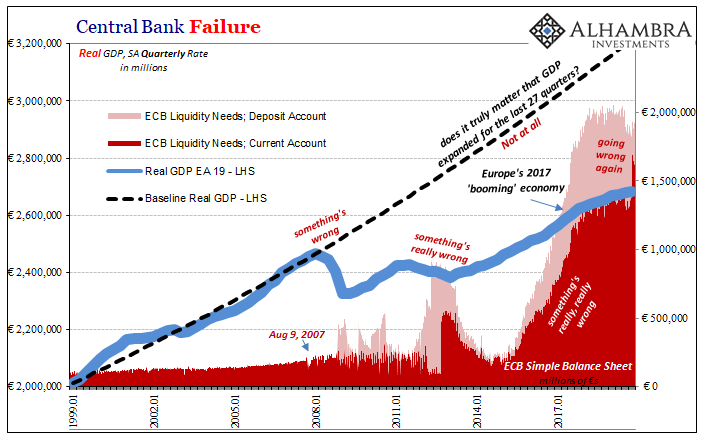

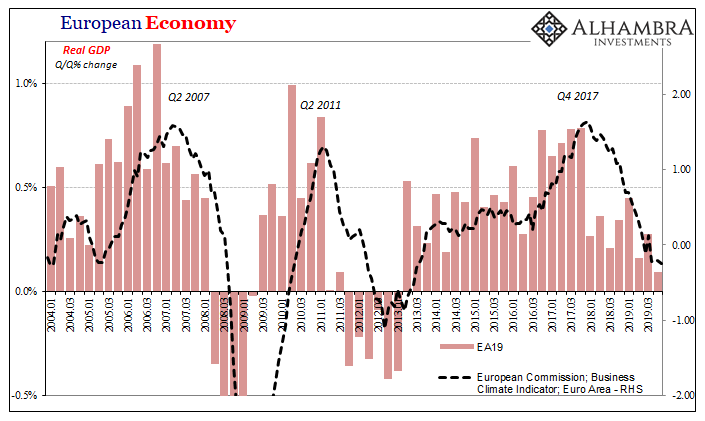

According to Eurostat last week, Europe’s win streak reached 27 quarters in Q4 2019. If you count winning solely by the sign in front of quarterly GDP changes, then Mario Draghi handed off to Christine Lagarde an expansion just one quarter shy of seven years. It’s supposed to be impressive.

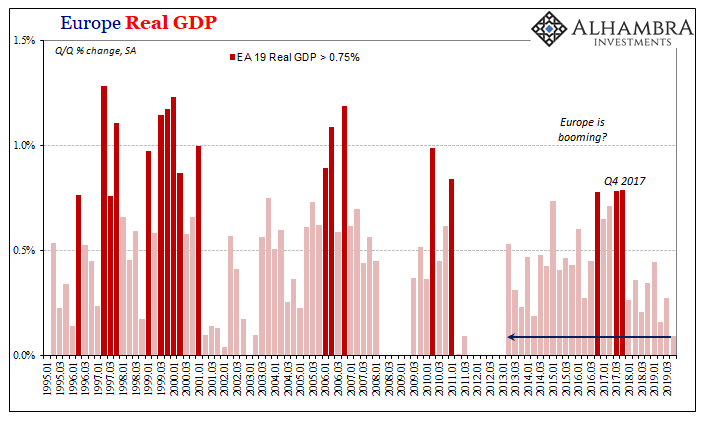

Lagarde, however, begins her tenure in very much the same way as Draghi began his. Europe’s economy just barely kept the streak alive. Eurostat’s preliminary estimates show real GDP in the EA19 increased by the tiniest amount, rising just 0.094% in Q4 when compared with Q3 (seasonally adjusted). That was down from the prior quarter’s seemingly anemic +0.274% (revised).

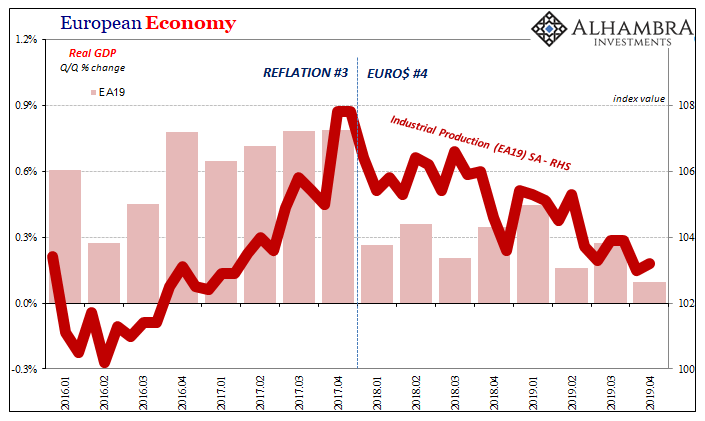

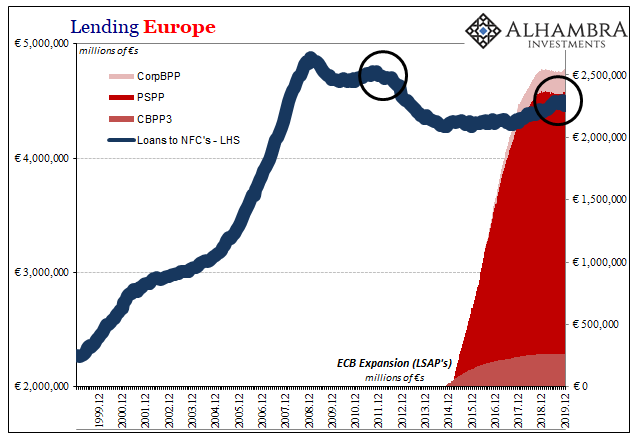

While the world’s attention has turned away from Europe and toward the supply of flu masks available in Asia, we shouldn’t forget that the European economy has been in the leading position during this entire downturn. And there’s no sign it is doing what everyone says it’s doing. With Draghi’s final gift of a relaunched QE combined with NIRPier tiered NIRP, things over there are alleged to have been looking so much better.

Thus, while Europe has so far managed to stay out of recession you can’t say that it has avoided one. Defying business cycle conventions, the squeeze on the European economy has totaled eight of those 27 quarters classified under “expansion.” Eight. That’s two years of a slow grind downward.

Just as PMI’s can be temperamental on a short run basis, GDP can manage to be, too. It’s not a straight line, but the trend is visibly intact nonetheless. Quarterly “growth” got as low as +0.21% during Q3 2018, then “rebounded” for the next two quarters pushing up to just shy of +0.45% by Q1 2019 – bringing with it all the usual sighs of relief and reinvigorating Mario Draghi’s flagging confidence about ending the the first (two) QE during that timeframe.

Then GDP decelerated again in Q2 2019, just +0.159% a multi-year low, lower than Q3 ‘18, before rising in Q3 ‘19 to +0.274% as noted above. And now lower still to basically the smallest you can get on the good side of zero. No growth in Q4, but no minus sign, either (though that could change after revisions).

It doesn’t follow the V-shape consensus nor does it suggest where and when this downturn will end. It just keeps going lower such that everyone merely assumes that it cannot, especially after two years and counting. Throw in some good “stimulus” from an overly cautious ECB, that’s the basis for this optimism.

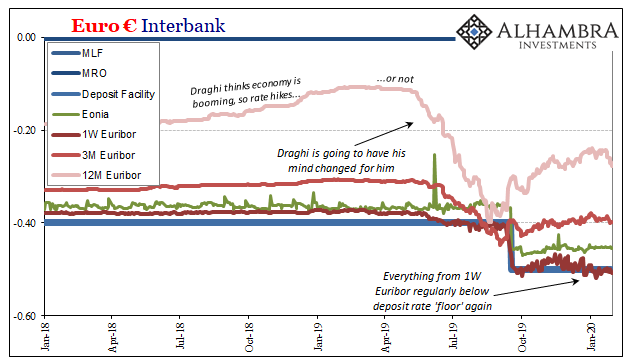

It’s really not much, if you are being honest. Assumptions about time which long ago proved inaccurate, and the “stimulus” which deserves the quotation marks each and every time the word and the marks are rightly placed together. As a reminder about “stimulus”, look no further than the righteous mess in euro money markets below (and here I thought 2015-16 qualified as a mess).

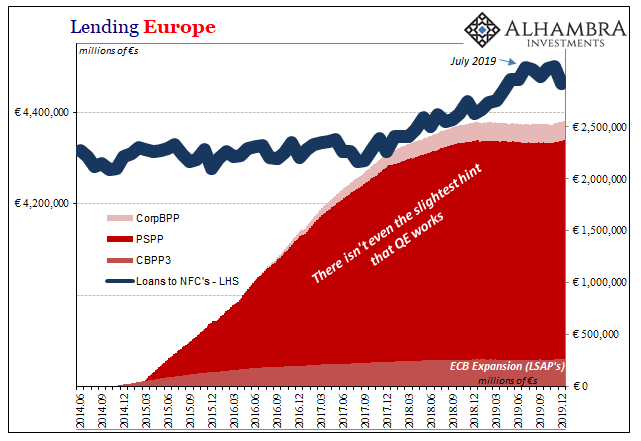

The immediate hopes for these ECB actions have been on what they’re supposed to do for European banks (in the case of NIRP, to European banks). Why anyone might’ve thought monetary policy would help is beyond all evidence. QE (and NIRP) is the most tested monetary theory in history and the results everywhere it has been tried conclusively demonstrate it is never, ever more than puppet show, one that it’s audience is becoming tired of witnessing.

It is “stimulus” only in the sense the word is used every time by the financial media. Other than that, nothing gets stimulated especially where banks are concerned.

And that’s got to be Christine Lagarde’s big concern right now. Lending data in Europe is beginning to rollover – already has been rolling over. This could indicate a very possible cyclical change in banking behavior (risk aversion and balance sheet squeeze). It’s most obvious right now just where the ECB doesn’t want any weakness to show up.

Loans to non-financial corporations. Business lending.

The presumed positive effects of monetary policy show up with a lag, but since they are presumed rather than established through any other means than myths and assumptions, I’m not sure on what basis anyone should take them seriously. I mean, did you see the euro money markets? Not to mention European banks packing stacks of physical cash away in vaults like this was 1893.

Some indications for sentiment suggested things were turning around in Europe during the fourth quarter. There isn’t much if any data behind the sentiment. If anything, the downside case strengthens the longer it goes on having surpassed, several times, all the prior “bottoms” that have been indicated and forecast.

If the banking system has turned where loans are concerned, that’s pretty much it. What would follow at that point would begin to look more like a classic recession, including negative GDP numbers. Europe isn’t that far away right now, so it might not take much more than a minor shove.

This was always the problem as far as time was concerned; the mainstream idea is that the longer weakness goes without turning into a recession, the more likely the economy, whichever economy, will avoid one. The squeeze scenario, however, goes the other way. The longer the downturn lingers, the greater the risks it becomes something greater.

Mario Draghi did squeeze eight more quarters out this “expansion” to cap his tenure. Hardly ending it the way he’d likely imagined, those two years were increasingly fraught with at best uncertainty and nothing like growth, however. So, while the 27-quarter streak may be ending, if it hasn’t already, the 8-quarter downturn might still just be getting started.

Not a great development for Europeans, nor anything good for the global economy. The world is looking at virus-stricken China for guidance as to where things go from here, but we shouldn’t forget about Europe for its more basic clues and cues.

Stay In Touch