As you might imagine, inflation was the hot topic of conversation during the December 2014 FOMC meeting. Having opened up the transcripts for that year to the public last month, we are once more treated to the background behind this theater of the absurd. The final few months of 2014 were when everything came together.

For these central bankers, it was surely the launch point for the long-awaited recovery – even though by every major market-based reading it would prove to be the end of that very thing. The “best jobs market in decades” had brought the unemployment rate down quickly, QE was being terminated, and rate hikes on the agenda for the first time (seriously) since 2006.

As a consequence, the term “inflation expectations” was used 97 times during the discussions.

Already there was a problem, however. There is always a problem. In December 2014 you might remember what that was in this context. While committee members like Richard Fisher from Dallas spoke of Saudi Aramco and the Texas oil free-for-all, the “supply glut” theory would keep coming up short of explaining fully what was going on with oil prices. Reality didn’t keep it from the center of the official conversation.

It was all temporary, they said. While the supply was brand-new for these central bankers it should’ve been preposterous to assume it was also unforeseen by futures markets. But that would’ve required looking at the unfolding oil price crash in another way, like the surging dollar the uncomfortable way.

As a consequence, those like San Francisco branch President John Williams (since promoted, of course, to lead the New York branch), the Fed’s main R* guy, refused to believe his own lying eyes.

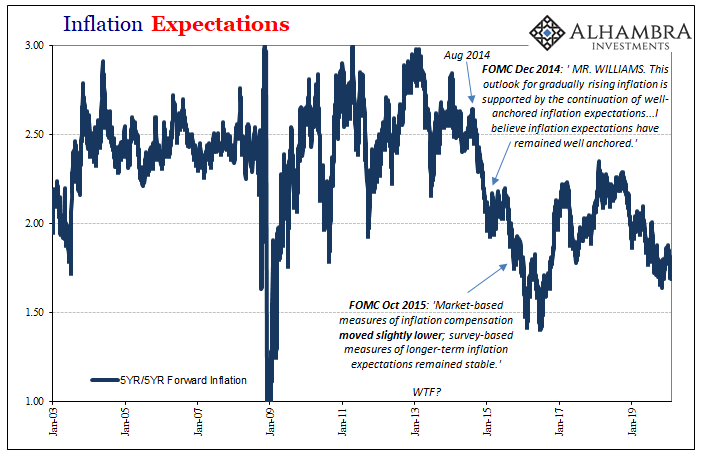

MR. WILLIAMS. This outlook for gradually rising inflation is supported by the continuation of well-anchored inflation expectations. I agree with President Fisher, I believe inflation expectations have remained well anchored.

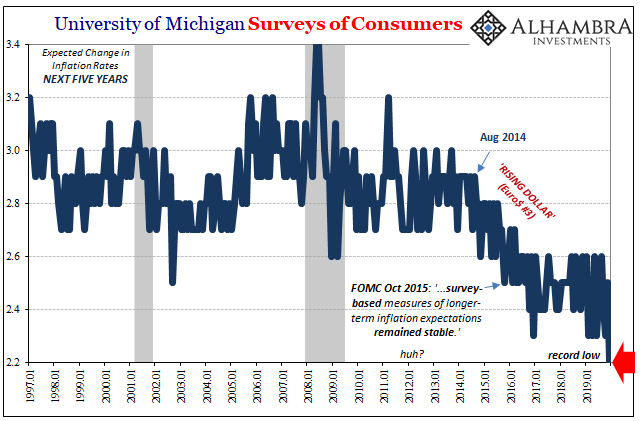

Both near term and long run market-based inflation expectations had already begun their plunge along with WTI. Setting them aside, Williams pointed to survey-based measures of the same. Markets were imperfect thus household surveys superior, he concluded, because there might be some Singapore financial groups buying TIPS off the back of Middle Eastern speculators splicing growing contango profits. Or something.

MR. WILLIAMS. I am unconvinced that market prices likely reflect the preferences of American households in the way that the memo lays out. One reason is that a large share of American households doesn’t actively participate in financial markets. Indeed, the marginal investor could well be a foreign hedge fund, which would invalidate the welfare rationale for using market prices.

Ultimately, of course, it didn’t matter. Within months it became clear survey-based readings on intermediate and long run inflation expectations had already joined the markets in saying John Williams was all wrong.

He and the rest of the FOMC were fooling themselves – and you really, really have to read these transcripts to truly appreciate the pure mental gymnastics, the lengths to which these people will go to deny what’s happening right in front of them. Truly remarkable, only slightly less marvelous than the Fed’s ability to keep the media on its side through twelve and a half years of this.

Internally, there wasn’t nearly as much rousing confidence as had always been projected outwardly. Some voting members of the committee and some members of the staffs were getting concerned that something was up with inflation. Therefore, recovery and economic potential. The biggest big picture.

What had triggered Mr. Williams’ diatribe and had sent him off taking up pages of transcript was a couple of included memos (he referenced only one in the quote above) presented to the FOMC on the topic of…inflation expectations. A Minneapolis branch staff paper on the subject published in August 2014 had already concluded that it might be a mistake to write off the market-based inflation outlook.

A second one from the Fed’s Division of Research and Statistics published only a week or so before this meeting, now available to us for the first time, was more conventional. The kind of context we’ve been hearing about for the half decade since that FOMC gathering, the possible end of macro slack and the tightening in the labor market.

Why isn’t inflation like the unemployment rate?

And remember, this was December 2014.

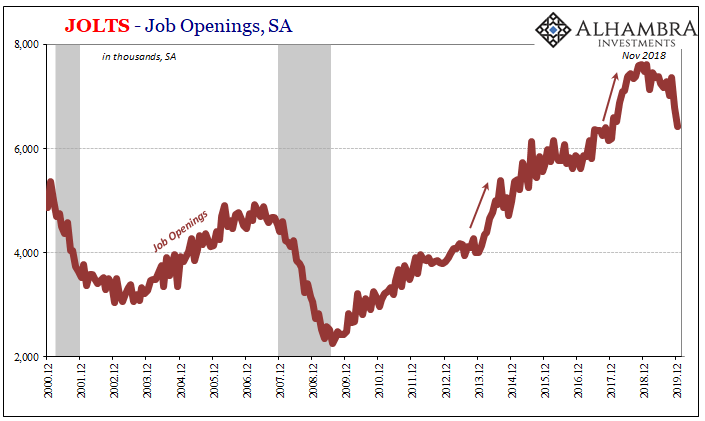

In particular, the JOLTS job openings rate suggests a much tighter labor market than does the unemployment rate gap. In contrast, the unusually wide labor force participation rate gap and elevated share of involuntary part-time work—margins of underutilization that are not captured by the unemployment rate gap—suggest that the unemployment rate gap somewhat understates the true degree of slack the in labor [sic] market at present.

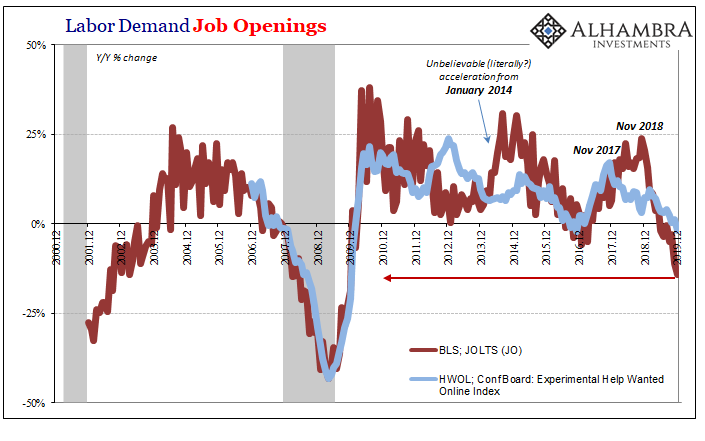

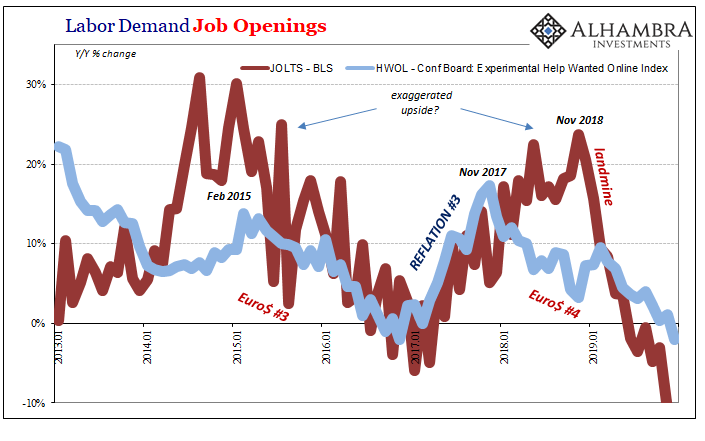

From this perspective, it’s pretty simple stuff. All the TIPS market said was that the more time passed and inflation (particularly wages) didn’t break out the more likely the unemployment rate was faulty (and by extension monetary policy). It was hard to conclude anything other than how it was misrepresenting the macro slack that was present in December 2014 for the reasons cited in the memo. JOLTS Job Openings was the outlier among several other indications siding against the unemployment rate.

Janet Yellen never told you that part as she continuously pointed to job openings.

And with oil prices crashing, that pissed off John Williams something awful. He could see what that would mean, at least one more year where the headline inflation numbers would significantly underperform. He was sick of all that; it had already been five years, four QE’s, and a Twist.

Williams was in a rush to declare victory. The oil market would digest the transitory supply glut, he declared, and not so long afterward by 2016 the inflation numbers would confirm his predetermined viewpoint. The market, looking at it differently, was standing in his way.

It still is today.

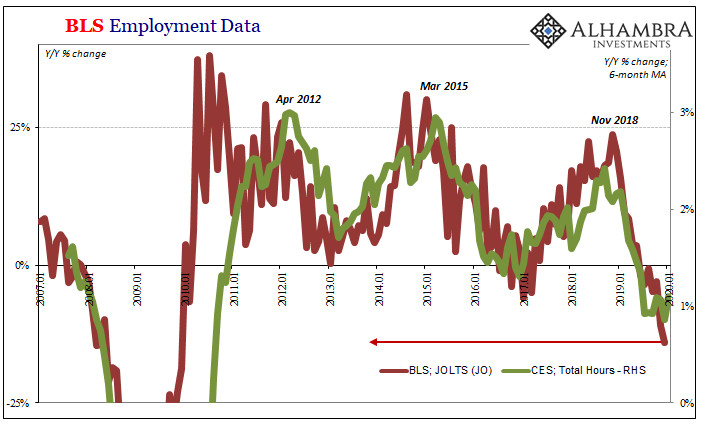

The unemployment rate is now lower yet inflation is practically the same, and oil prices are probably pissing off John Williams right now as I write this (contango, too). One thing that has changed is JOLTS and Job Openings.

JO was among the few to suggest a tight labor market. By the middle of 2015, like crude it had turned against the central bank, too.

Today, it’s even worse.

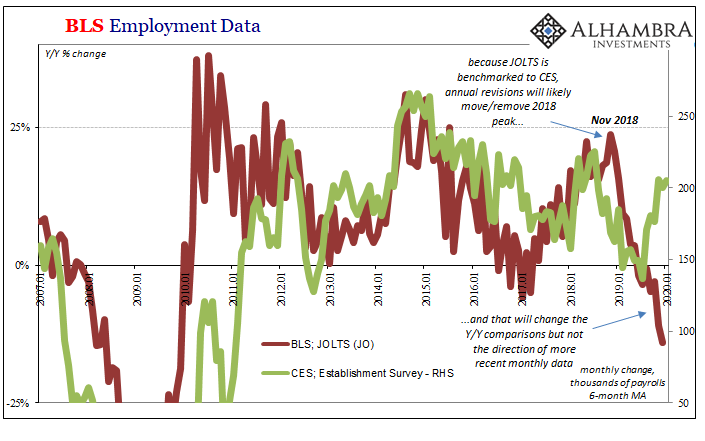

According to the latest numbers from the BLS, the demand for labor is falling off at a torrid pace. Now, that part is likely to be revised next month when the most recent benchmark revisions show up in JOLTS (it is a month behind the Current Employment Survey, and is, in fact, benchmarked to it).

What that will mean in all likelihood is the skyrocketing job openings that everyone used in 2018 to try and confirm the unemployment rate view of epic labor market tightness will just disappear. Poof, it’s gone. Like the announced revisions to the Establishment Survey, JO will almost certainly begin its dive several months before what’s indicated now and from a much lower peak level.

It will almost certainly be one more way to explain how the “hawkishness” and inflation hysteria got to be so out-of-control. Real hysteria based on very little perhaps nothing in the real world.

But if 2018 hadn’t been nearly so good, 2019 and therefore 2020 won’t be revised upward like the Establishment Survey has been. Instead, the latest downturn in JO will still be there next month, and what all of this together says is that officials have no real idea what they are talking about.

Only in this case, the data says the labor market is not just coming up short it really is cooling off. That hasn’t yet meant layoffs, more along the lines of a deepening hiring freeze at a very inopportune time – that’s why the demand for marginal labor, JO, is being scaled back even if we aren’t sure right now by how much.

The labor market probably wasn’t anywhere close to what they had hoped at the end of 2014, and it is still that way to begin 2020. And yet, in the media and in the mainstream these people are taken seriously. In the bond market, though, that’s another story and almost surely why John Williams distrusted it back then and continues to take his vain potshots at it now.

As interest rates fall lower, the middle finger is being hoisted right back in his and the FOMC’s direction. The feeling is mutual. Unlike in the media, bonds have seen more than enough.

Stay In Touch