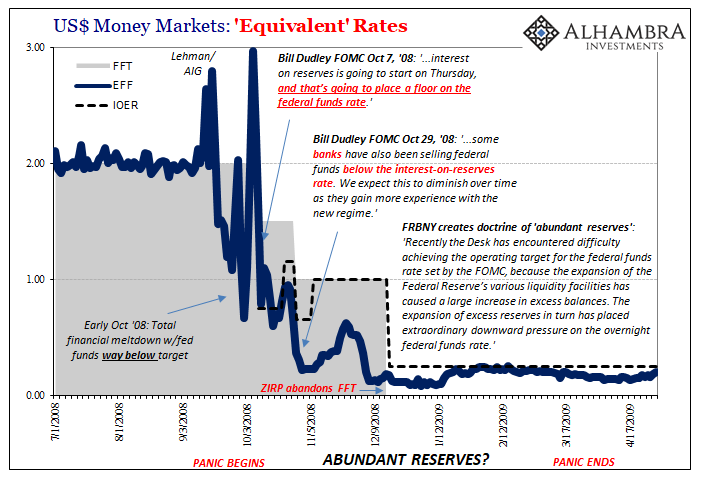

When you focus exclusively on bank reserves, even when the answer is staring you in the face you just can’t appreciate it or decipher the implications. Nearly six months later, they still don’t know what happened in the repo market last September. By “they” I mean, of course, the Federal Reserve including all the presumably technically proficient operators at its New York branch.

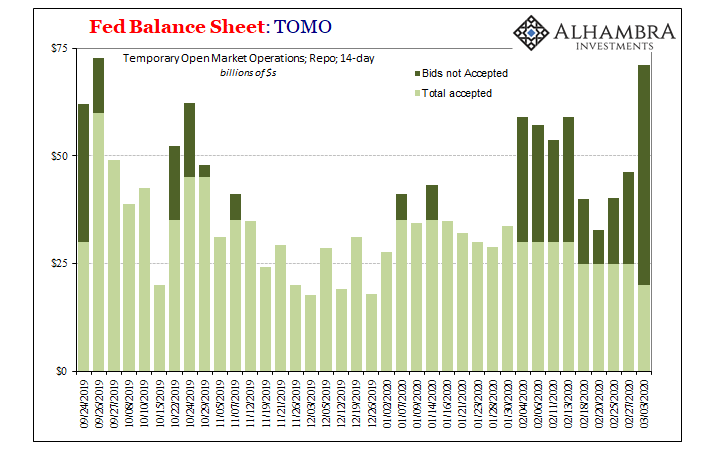

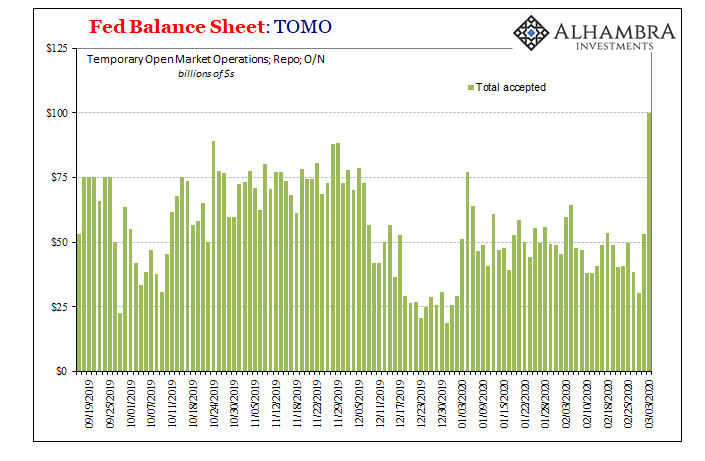

Going back to early February, this year, FRBNY’s repo operators have been busy again. The market, meaning the primary dealers, are in demand for these supposedly excess funds the central bank puts on offer.

These busier days, especially term, contrast with policymakers’ view of the situation. They’ve been attempting to wean the primary dealers off of their so-called generosity. The amount allotted (at term) has been pushed lower even as demand grows (see below).

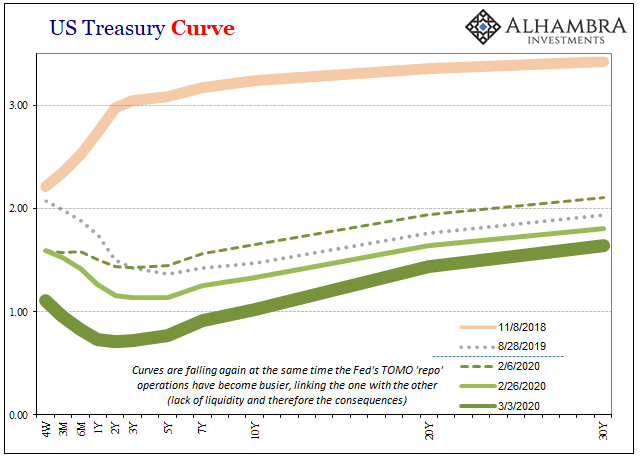

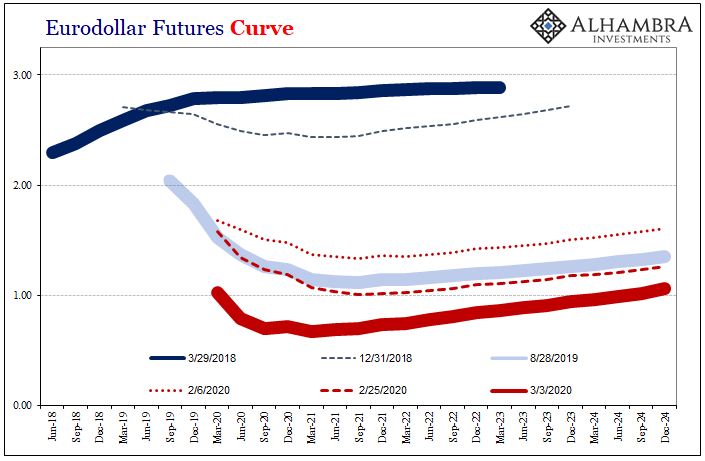

While officials are blind to the correlation we are not; that is, what curves have been doing since early February. At the same time dealers have stepped up their demand for the Fed’s funds (not to be confused with fed funds) the yield and eurodollar futures curves have utterly collapsed (huge liquidity indications).

I’m not saying the one causes the other, rather how both of these things are pointing at the same thing. Risk aversion is akin to tightness in the monetary system, therefore balance sheet capacities. That goes especially for dealers, who are that system’s central redistribution point, not the Fed, as well as for other lesser known and smaller quantity players.

But if we can so easily establish the connection, why doesn’t it register where it should?

Several staff members at FRBNY have just published a paper on last September’s repo rumble. There are, actually, several good points contained within it starting at the top with the very problem everyone should have been lasered-in on all along:

Moreover, frictions in the interbank market may have prevented the efficient allocation of reserves across institutions, so that although aggregate reserves may have been higher than the sum of reserves demanded by each institution, they were still scarce given the market’s inability to allocate reserves efficiently.

It’s the official way of asking the question I asked from the very beginning: WHERE ARE THE DEALERS?!

First, though, the good parts of the paper. As anyone who is or might have become familiar with the repo market has heard, most of the “explanations” offered for September (as well as the general tightness which was perfectly apparent well beforehand) offer up regulatory restrictions as their primary suspected culprit.

Basel 3’s LCR and whatnot, perhaps something to do with a G-SIB designation.

As I’ve pointed out, those never made much sense for the very reason FRBNY’s people finally get around to admitting:

Since Basel III regulation had been in place for some time, it is not clear why its effects on money markets would have been exacerbated in mid-September.

So, in the authors’ (there are six of them) view, what was the cause of the “market’s inability to allocate reserves efficiently?”

Well, they don’t actually provide much of a direct answer to that question. It’s as if they admit dealers were absent and leave it at that; as if pointing to their absence is enough of an answer.

That doesn’t mean they don’t deliver some substantial discussion on the topic, it’s just that the discussion ends up with mere conjecture. More assumptions that are based upon a bank reserve, Federal Reserve-centered perspective.

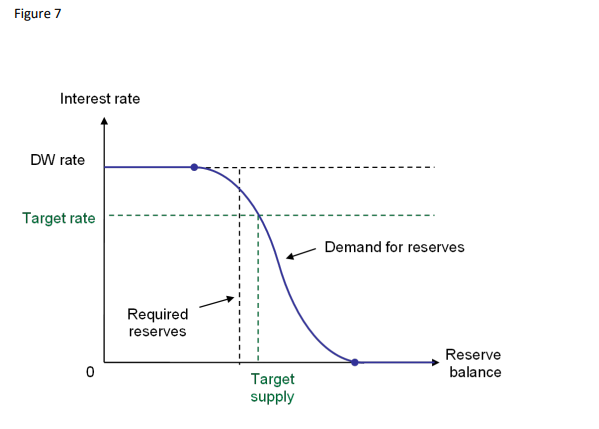

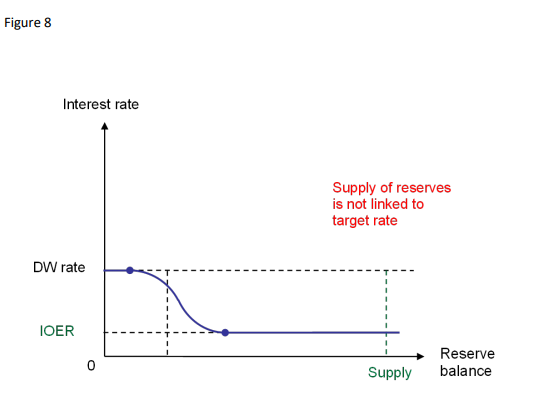

It all begins with the absurd and demonstrably fallacious doctrine of “abundant” reserves. Because this is taken very seriously, staff Economists (and not just these six nor just those at FRBNY) have developed a model (attempting) to understand how money markets must work when the Fed’s balance sheet is so large.

Here it is:

Given what happened in September, a sharp rise in rates, more so in repo than fed funds, starting from the model you see above you are forced to assume that conditions on those days were in the steeper part of Figure 8’s S-curve. Since the supply of reserves no longer determines the interest rate, abundant reserves, the “demand curve becomes flat around the level of the IOER rate” as the authors write.

The difference between Figure 7 (pre-crisis) and Figure 8 has to do with that steep part; in the pre-crisis era where bank reserves were minimal the steep part was, everyone claims, well-known and easy to define. That’s what supposedly made Alan Greenspan’s job so effective.

In the post-crisis era it is much harder to determine.

And since repo rates skyrocketed in September with QT having drawn reserves down to their lowest levels in years, the staff therefore claim the two must be related – that clearly money markets had entered the steep part of the curve which just so happened to coincide with lower systemic levels of bank reserves.

They make this leap even though banks have consistently told FRBNY and the FOMC that they weren’t close to individual minimum levels.

Thus, the authors have more explaining to do in terms of why dealers, in particular, failed to intermediate in repo despite this fact.

Instead, they are blaming sponsored repo and specifically money market funds, for reasons that aren’t very clear, pulling out of it leaving dealers who might’ve been able to intervene unable to do so.

The retrenchment of MMF funding from the sponsored repo program likely increased the average intermediation costs faced by institutions lending in the interdealer market. Indeed, as explained in section 1.2, funds borrowed through the sponsored program can be netted against fund lent in the FICC cleared interdealer market. In contrast, funds obtained from other sources typically cannot. As a result, the MMF pull back likely increased the average intermediation costs of US GSIBs; that is, the additional regulatory cost of lending due to a loss in the ability to net. Put differently, the rate required for US GSIBs to increase their net lending in the repo market likely rose.

This gets a bit complicated, and I’m summarizing several pages of text and argument here. Still, the idea is that by removing a source of possible netting in sponsored repo it made it more expensive for dealers, who, by the way, did actually step in during the September event, to redistribute funding.

If costs go up then the return, or spread, must as well. While true, it doesn’t really give us any insight into why “costs” must have gone up so far.

It is wholly unconvincing. What the paragraph above describes, when you step outside the “abundant reserves” worldview, is nothing more than risk-averse behavior – which just doesn’t compute in an abundant reserve, economy-is-awesome set of circumstances.

Not reserve scarcity; dealers who felt they required a huge spread in order to release funding in a market that had grown uncertain – signaled to them by the initial burst of higher rates, which then caused dealers to pause and pull back, allowing the rate to go higher still, stoking even more risk-aversion, and so on. Classic self-reinforcing spiral.

In that sense, FRBNY has sponsored repo all backward. I wrote a few months ago:

Sponsored repo wasn’t trying to fix a problem in repo, it was invented as one possible way to do repo better under this questionable monetary environment of balance sheet, not bank reserve, scarcity. In a strange but very real way, DTCC was actually doing the Fed’s job! To get more (usable) money into the system by trying to squeeze blood (funding) from a stone (balance sheet capacity).

That’s the problem with treating bank reserves in this conventional way. You start by assuming there is and must be plenty of liquidity without ever stopping to wonder if that is true. And then when something happens you’re off reverse engineering a solution to a problem you have all backward.

Even after blaming sponsored repo the paper admits that leaves them with even more questions.

While the MMF pullback from the sponsored repo program can help explain why repo rates increased more than expected, particularly in a context of scarce reserves, it is unlikely that these facts alone are enough to explain why the repo rates increased as much as they did.

The MMF activities don’t really help much at all to figure out September. What happened in repo was, again, classic risk-averse behavior, just like we’ve seen all across the bond market (again) recently. Dealers know, unlike FRBNY staff, that FRBNY is of little help to them whenever things turn ugly. At the slightest little hiccup in September, a dress rehearsal, they pulled their limited, precious balance sheet capacities out of the repo market – at almost any price.

In February and now March 2020, the same thing is disappearing. Except, it’s not just or even much repo. It’s disappearing from everywhere at the moment. Liquidations galore. The very thing September’s repo dress rehearsal was rehearsing.

The level of bank reserves? Substantially higher than September, of course. Then again, the next FRBNY paper will have to tackle why rate cuts didn’t ease, either.

Stay In Touch