The Federal Reserve conducts reverse repo operations (RRP) daily, and has for more than half a decade. These are very different from the “liquidity” operations the central bank has been deploying since last year’s rumble in the repo market; the latter merely mimic a repo transaction and are intended to push bank reserves the Fed creates on the spot out into the Primary Dealer network.

A reverse repo, as the name implies, is the reverse of that transaction. Its purpose therefore is not bank reserve-type liquidity but to establish a floor for depository institutions. Those who are cash rich have the option of “lending” that cash to the Fed receiving in return SOMA holdings as collateral.

Given that option, who in their right mind would ever lend into money markets at a rate less than the RRP? That’s the floor. As far as risk goes, you’re never going to do better than lending cash to the central bank on pristine collateral.

This goes for money markets and money equivalents alike. A 4-week T-bill, for instance, is a money equivalent in this sense. Why would anyone lend to the US government at a return less than what they would get at the RRP? These are near equivalent transactions; in the former you are left holding a 4-week bill while in the latter you’ve received government debt as collateral.

And if the RRP is set to zero, as it is now, you’d have to be crazy to hold anything at a negative yield. Especially short-term bills. Why bother paying the federal government to borrow from you when, if you have the cash, you can just go over the to Fed and at least park that cash safely collateralized at zero.

Negative bill yields are further clarifying and demonstrating the usefulness of those instruments beyond any investment or carry trade function. They have a separate utility that is, at times, of enormous value. Financial counterparties during those times are willing to pay a penalty, either the negative yield or the opportunity cost of not using the RRP, this week both, in order to secure and hold on to bills.

I’m obviously talking about collateral for use in repo markets. T-bills are the most pristine of pristine collateral; always on-the-run therefore liquid beyond anything else, and containing very little interest rate let alone credit risk because of their short-term nature. It doesn’t get any better as far as any repo counterparty will ever be concerned.

Negative yields below the RRP cannot be anything else. And it’s just the starting point for the collateral case.

Before getting to the rest, we’ve documented the string of evidence pointing in that direction for longer than I care to remember. May 29, 2018, the “strong worldwide demand for safe assets” that first flattened and then ran over the yield curve, inverting and twisting that thing into a grotesque shape the implications of which only a central banker could misinterpret.

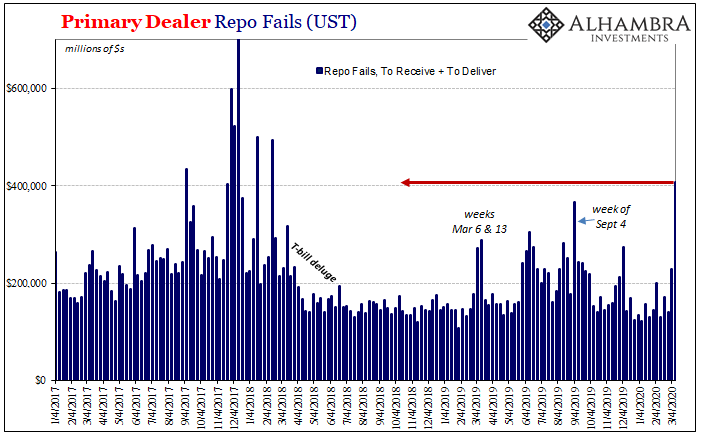

There’s also been repo fails, a clear but definitely fickle sign of the collateral shortage. It’s never one-to-one with fails, as you might expect. They show up quite often as confirmation before or during, but not always consistently.

Still, it wasn’t surprising to find that FRBNY reported late yesterday how fails during last week (3/9 to 3/13), a particularly momentous week in markets, surged to the highest level since the early stages of Euro$ #4. We’ll have to wait until next Thursday to see how high they might have reached this week.

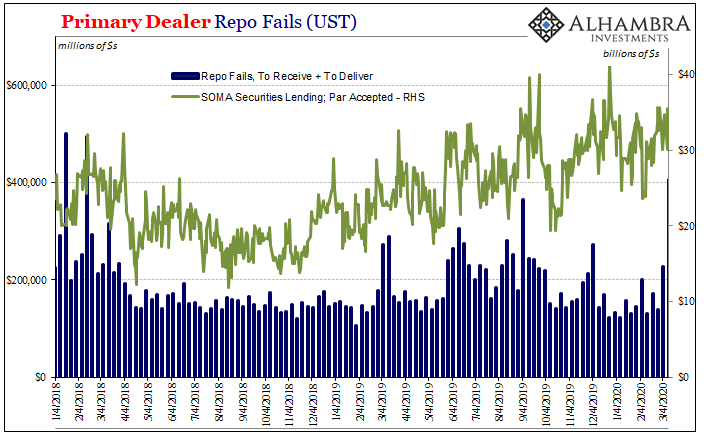

Not only that, the general rise in fails during 2019 correlates rather well with FRBNY’s other data on Primary Dealer demand for collateral. Dealers are eligible to “rent” securities out of the SOMA portfolio via the FOMC-authorized securities lending procedure.

A data limitation for both is that they only capture what gets reported to FRBNY by the dealer banks. Any collateral issues beyond them in the incomprehensibly expansive system outside of this one visible part of global US$ repo go unreported – but not unnoticed.

It is entirely possible, I would argue a certainty, that the real collateral conditions out there in the rest of the repo piece of the shadow money system aren’t being properly represented by these dealer-centered statistics. They seem to be portraying only what shows up at their doorstep – which is still considerable.

Unlike during GFC1, in this GFC2 the dealers, at least, are far better prepared including having built up collateral reserves the whole time the yield curve was collapsing. It’s one key reason why I’ve said that I don’t think we’ll see another Lehman or Bear Stearns this time around.

But what about everyone else?

Instead of fortifying the system, these “fortress” balance sheets (as JP Morgan’s came to be known) have simply moved the bogey further into the shadows. Sure, JP Morgan might make out fine liquidity-wise but what about the rest of the system that depends on JPM as well as its peers taking on risk? Sitting on the sidelines creates islands when the world needs a contiguous ocean.

Those risky dealer activities include collateral factors which expand the chains or streams of collateral flowing through repo markets. There’s a crucial multiplication process at work here, one that can enlarge the overall systemic stock of collateral and then contract it when dealers are more content to sit on the sidelines counting up their own stock of collateral reserves damn the systemic consequences.

In other words, fails and SOMA securities lending are good enough hints at global offshore shadow repo shortages in collateral, giving us a sense of what has made it thus far inward into the daylight, and therefore only a good place from which to start. If we’re seeing a collateral shortage show up in fails and SOMA, what’s it like further back in those shadows?

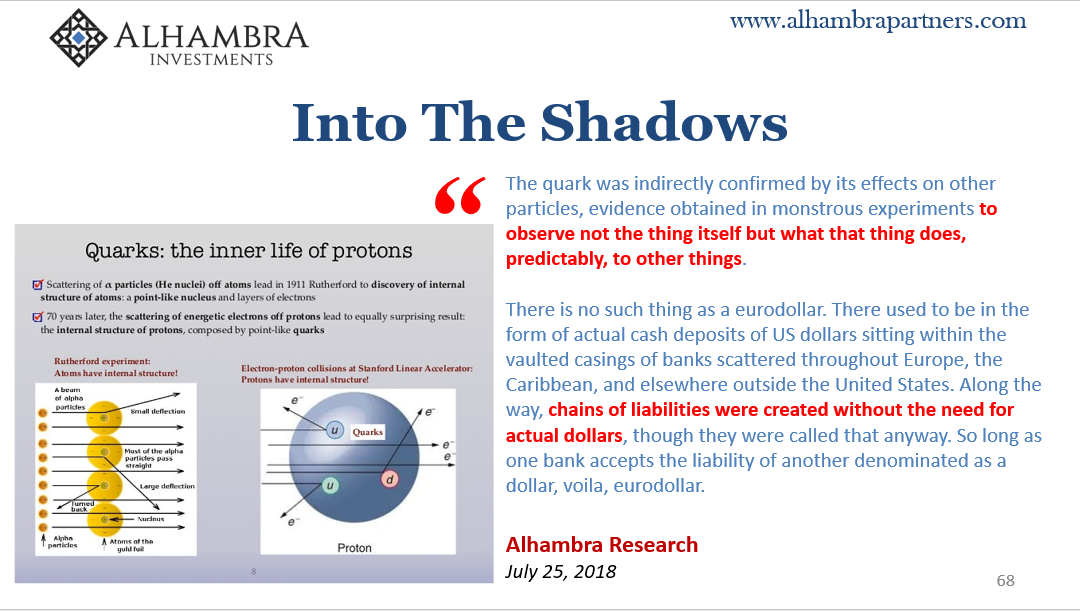

Since that’s really the way this money system is, opaque to put it charitably, we’re left to infer; chasing hidden monetary phenomenon means being able to properly analyze behaviors. Cause versus effect.

This is actually proper science; physicists have never been able to observe a quark, one of the most fundamental particles of nature, yet they know with certainty quarks must exist by the manner in which these things disturb the matter around them.

In this collateral case, we’re doing something similar. We theorize a collateral shortage starting with yield curves and repo fails, and then take to markets to observe how that shortage might be disturbing, well, pretty much everything.

This is actually pretty easy to do, and the case is overwhelming at this point. That’s the thing about these GFC’s, they are like high energy particle colliders physicists use to smash open the tiny, hidden secrets of the universe. In the monetary world, at high enough energies the same thing happens; everything collides and for a time the hidden shadow money world becomes briefly illuminated.

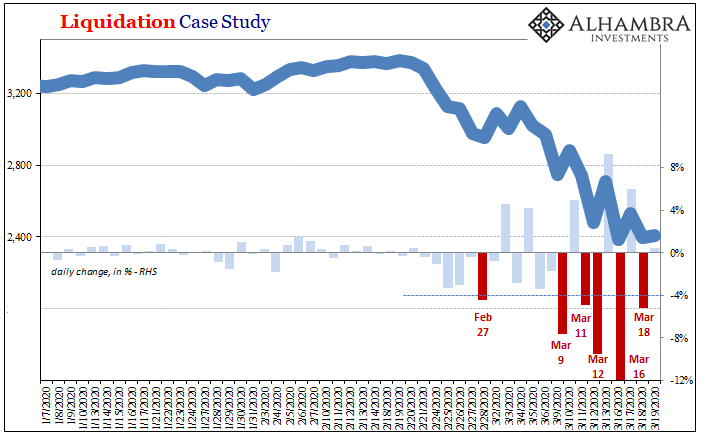

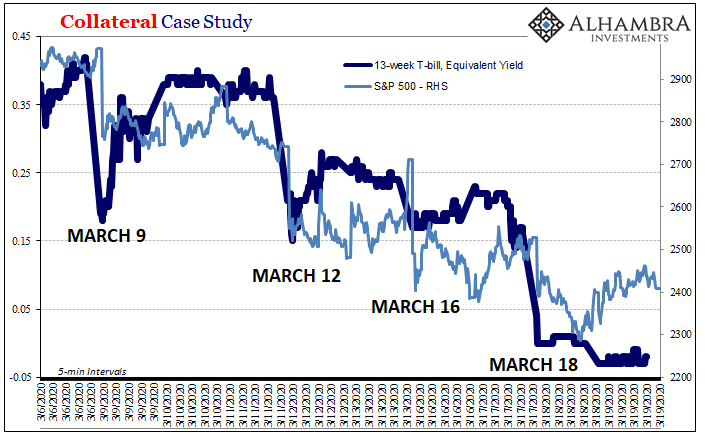

During this part of GFC2, it’s pretty easy to see what makes a modern market crash. Unlike maybe conventional wisdom, a crash isn’t a single day nor a straight line down; rather, it is a series of awful days strung together though not always consecutively. There’s a cumulative effect, an unsettling violence, the true sort of volatility in the wild swings up and down.

But more so the down. The selling adds up because of how and when it is done; liquidations, or fire sales. Three of the worst single days in stock market history happened in the space of one week, the last (so far) and deepest hitting the markets this past Monday. Nothing like it since ’87.

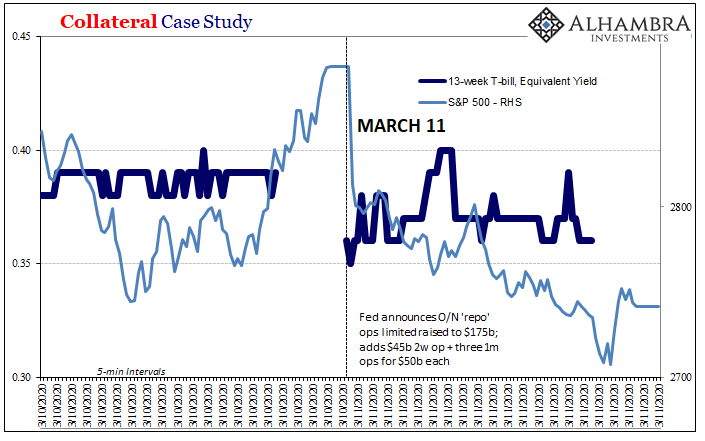

And during it all, the Federal Reserve completely helpless. Bazooka after bazooka, nothing. The fire sales only blistered hotter, currency, whatever may get defined within the term, near total inelastic.

In addition to fails and yield curves, we’ve also got the fact that central bankers and all their “liquidity” tools amount to nothing; less than nothing. They are most definitely missing something, too, otherwise currency elasticity wouldn’t be so hard to manage.

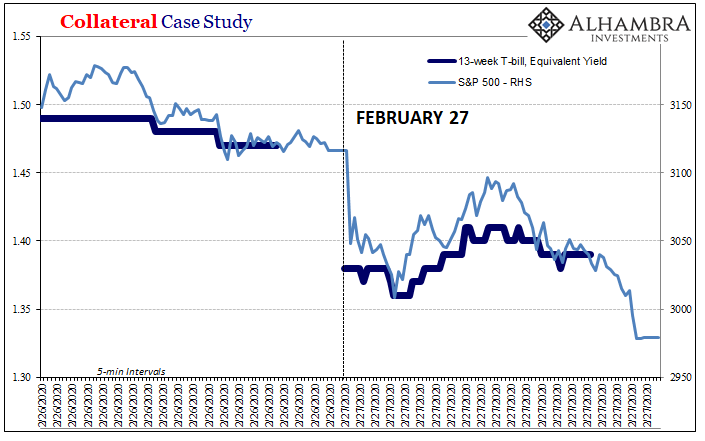

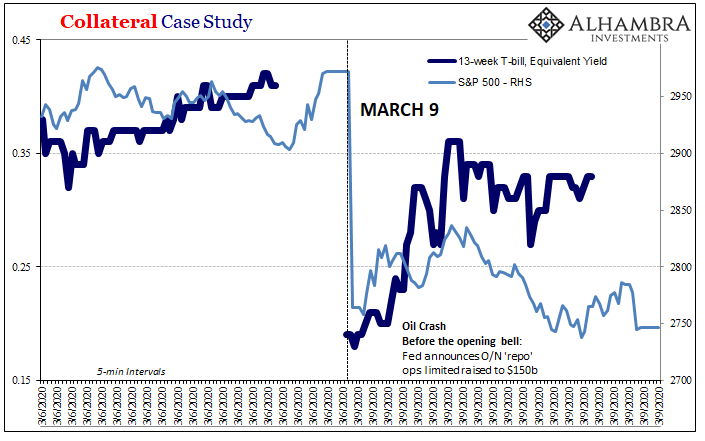

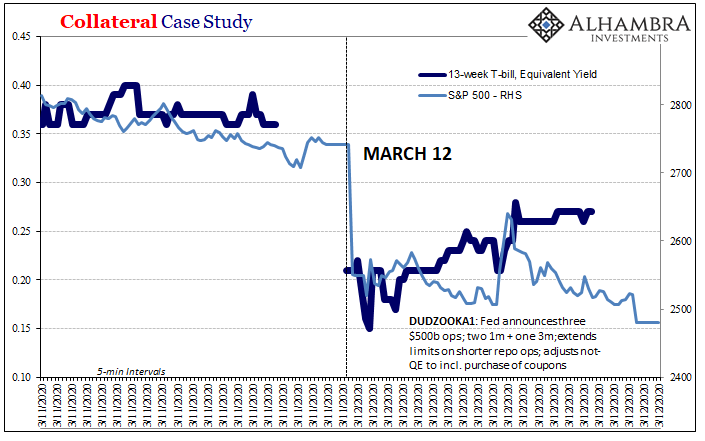

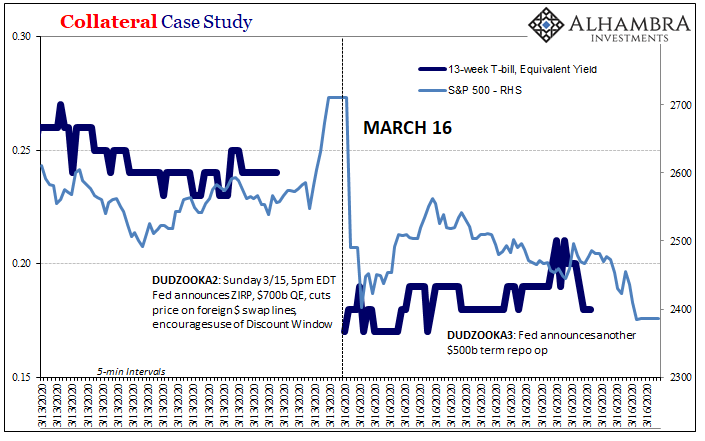

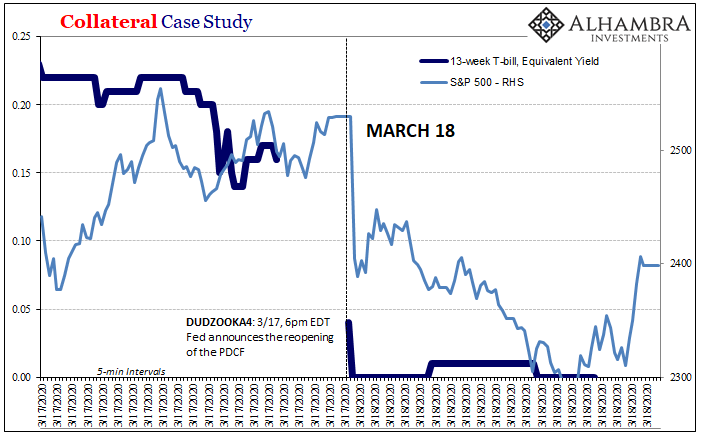

On each of these major liquidation days in the stock market we observe the unusual correlated behavior in Treasury bills. In the early morning hours, beginning before markets open for the day session, bill prices are bid sky high (therefore the equivalent yields, shown here, plummet way, way below the RRP – and this week below that and zero).

Day after day of these stock market liquidations it works out the same way. The hidden shadow collateral shortage can be the only thing which can so disturb these markets in these ways at these times.

Collateral calls mean in some cases using gold as a last resort (which gets dumped immediately) and in others the buying of pristine collateral at any price. Gold is slammed while T-bill prices skyrocket, their yields plummet. For those unlucky enough to have neither option in front of them, fire sales of assets including stocks and other risk credits.

Here’s the proof:

While repo books are being squared each of these days, the time when collateral calls are being issued (whether haircuts or demands for pristine as replacement of junk-y), bills are bid through the roof and stocks are liquidated into the morning session. You can add gold to these charts, too, though for clarity I elected to leave it off of this set.

We cannot directly observe the collateral shortage, but we can see very clearly how it has disturbed the markets unfortunately in the most destructive way. Some of the worst days in stock market history and some of the biggest downdrafts in bill yields, both taking place during the repo window.

What can be done about this? I’ll have more to say about that later.

Meanwhile, are central banks doing anything about collateral? Not really. The PDCF is at least aimed in that direction, but if you think it will be an effective tool just wait until you read how Fed officials view it. Blows my mind.

Is it over? In the short run, who knows. Over the intermediate term, not likely. Unless someone gets to Jay Powell by Monday, or he and the entire regime at the Fed rightfully fired over the weekend, they’re going to keep doing what they always do because as a bureaucracy routine rather than results are what matters.

Even when the case, and the proof, is overwhelming.

Stay In Touch