A crucial component of many commodity futures markets is a concept called roll yield. It relates to the shape of the curve and therefore how the market is discounting the three fundamental factors of supply, demand, and financing. Contango versus backwardation, there’s a lot to consider and even more at stake.

Back in late October 2018, the WTI curve flipped to contango warning everyone not mesmerized by Jay Powell how serious danger wasn’t just approaching it had already arrived. I wrote at the time:

For commodity investors, a roll yield opportunity can be everything. By rolling over a short-term contract into a longer dated one, speculators can profit off the futures curve regardless of short-term movements in the spot price. It helps police the curve, an arbitrage that aids good function. But only so long as the futures curve remains in backwardation.

In theory, it’s pretty simple. As you get closer to the front month futures contract’s expiration, you sell it and buy the next one in line. When the curve is in backwardation, the one immediately following is lower in price than the current, expiring contract you just sold. The result is you make a little money while remaining invested in the oil market.

That’s the roll yield.

You have to do this unless you want a tanker truck to show up in Cushing, Oklahoma with your name on the delivery sheet.

Unlike financial products like eurodollar futures which are cash settled, a commodity future such as WTI gives you the right to oil but also demands an obligation from you to take delivery of the stuff. Couple that with a curve in steep contango, meaning a hugely negative roll yield, and it’s a recipe for big trouble.

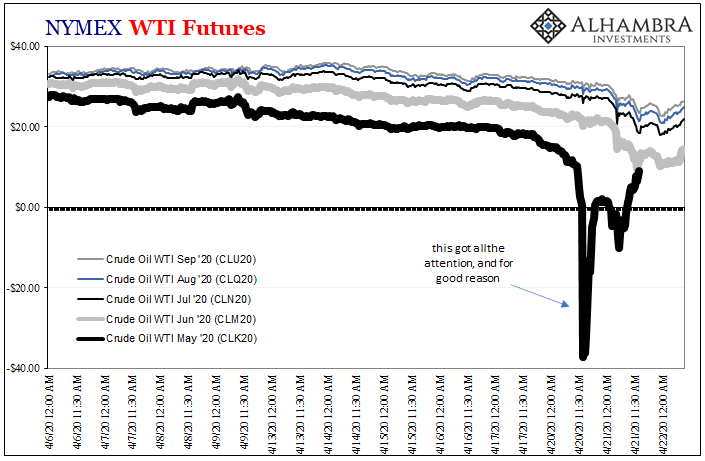

That’s essentially what happened on Monday. The May contract, the one obligating delivery of crude oil in May, was approaching expiration (yesterday was its final day of trading). With an epic negative roll yield, what were speculators to do?

Contango means that you’re either going to pay someone a nice premium to remove the delivery obligation, or you have to pay for storage. But what if all the tanks and spare pipeline space are used up, and at the same time no one wants to roll you into the future at almost any spread?

A deeply negative oil contract price.

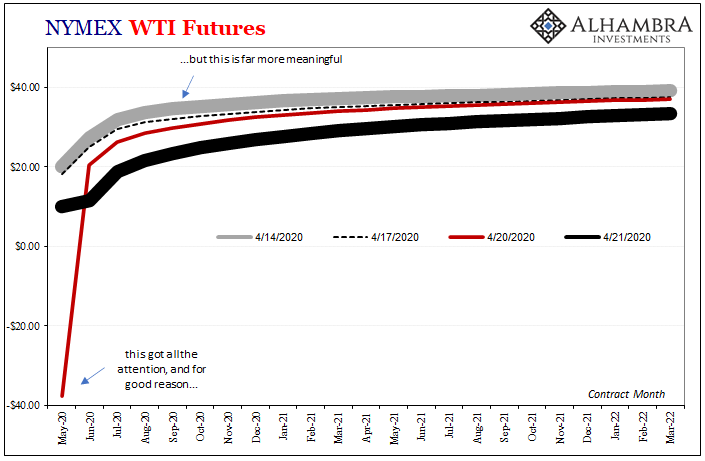

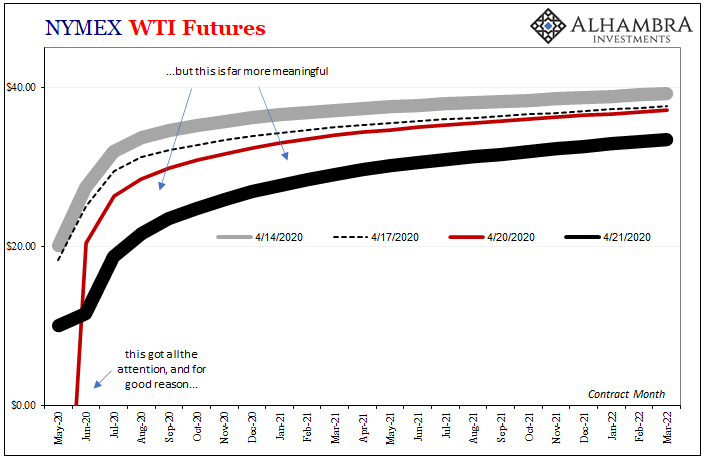

As important as this troubling result was, it still wasn’t the most impactful statement the oil market has been making. The more meaningful action has been playing out a little further down the curve, just as me and my Making Sense pod-cast co-host Emil Kalinowski had discussed just prior to Monday happening.

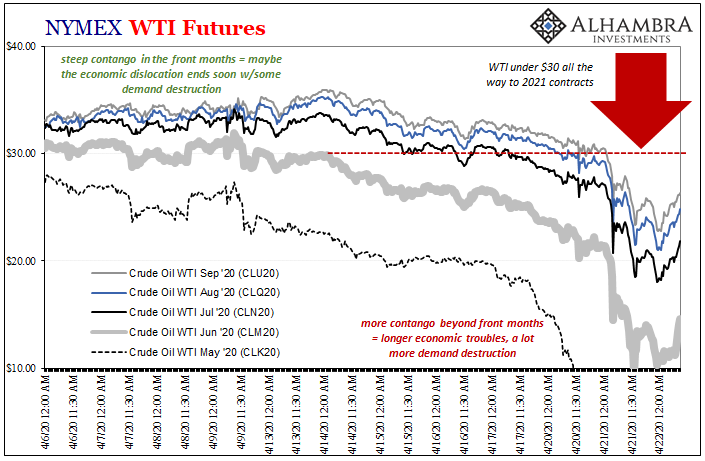

The more meaningful twists and distortions in future roll yield potential were being transmitted from the later contracts for this year – and beginning to affect those trading for next year delivery.

In the wake of Monday’s disaster, the WTI curve in the near-front plummeted, too. These contracts out to around October 2020 delivery didn’t see a negative number, of course, but their price did fall substantially below $30 a barrel.

There were many, factoring more optimistic outcomes for COVID-19, who thought everything would be back near normal by late summer if not early autumn at the latest. The same people were led to believe such a thing by their faith in massive “stimulus” in both its forms: the latest version of fiscal helicopter payments as well as Jay Powell’s mythical magic-ness.

How many of them were hanging around the May 2020 contract on the belief for a quick, V-shaped recovery? Like the Bond Kings, anyone listening to Jay Powell at crucial moments in economic and financial history can find it to be deeply painful.

I think Emil said it best; the ridiculous contango in the very front of the curve is really about near-term chaos. But if that contango peels off later contracts further down the curve, that can only mean the chaos is either lingering into the future at best or, sorry, Jay, spreading.

Monday’s negative oil price wasn’t nothing, literally less than nothing, but Tuesday’s curve collapse was the real earthquake. That’s the one that should have you thinking so much less about Jay Powell’s unsubstantiated, historically disproved quick “V.” The contango in the oil curve before this week showed how the majority were already skeptical, and now the few speculators who were taking his advice have just been taken out on a stretcher in a way that will long be remembered.

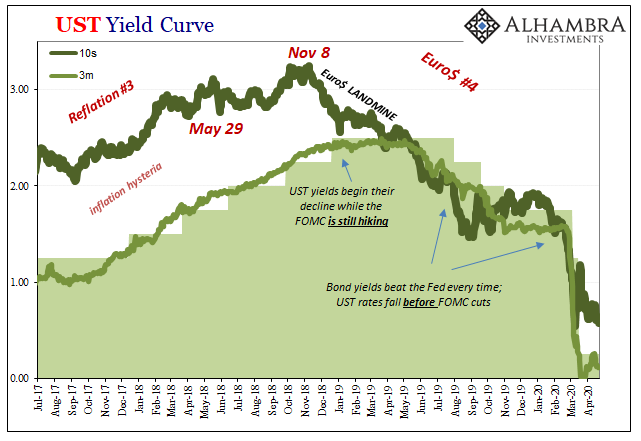

Back to what I wrote in November 2018, a time when the Fed Chairman was in the midst of hiking rates and thinking 2019 would be filled with even more of them:

Jay Powell is still hawkish, but the computerized commodity pits in taking away the speculator roll yield should more than anything else to this point make him rethink his position. He won’t. None of them will. Not only has the economy failed to materially change out of its wretched eurodollar-driven baseline, central bankers have shown time and again they aren’t capable of evolving with actual data.

But suddenly the FOMC has been transformed into a master of crisis management? If anything, after what happened in March, the central bank has proven all over again that its performance is directly proportional to how bad things get. The worse the crisis, the less you can expect from policymakers. In that way, negative Monday May 2020 oil and its roll fiasco are most relevant and poignant.

And now the next “L” looms larger and it stands for Lesson and Long-run; as in, learn demand destruction.

Stay In Touch