What connects March 2020 with February 2008 as well as the Crash of ’87 all then with the Great Contraction which initiated the Great Depression? If you said economic and financial chaos, you’d be partly right. There wasn’t really much or any of that in 1987, though there was with the other three.

People including politicians and central bankers don’t seem to be aware of the difference. For those who grew up on the old Sesame Street cartoons, one of these things is not like the others. But why?

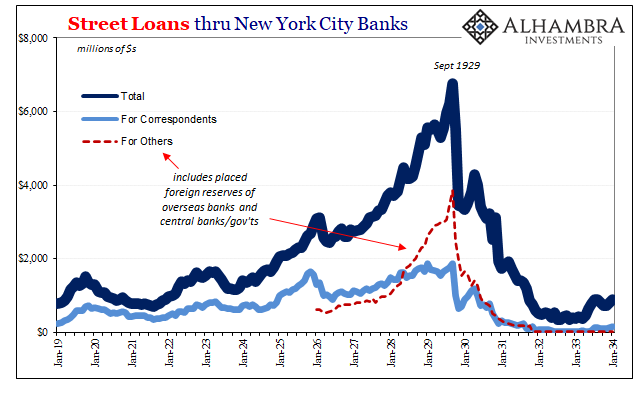

The Great Depression wasn’t caused by the stock market crash beginning October 1929, it was how the banking system had closely connected the monetary system with high-flying equity shares as a form of collateral behind loose money speculation. Called call money or street loans, this largely disappeared in the early thirties before the government (rightly) cracked down hard.

And when it did, owing to the conditions of the early Great Depression, a new way of thinking about money arose. The idea of currency elasticity was raised using the central bank as the main axis. Not only would the regular operations of the Fed need to be reformed, this would also require the granting of some kind of emergency authority beyond what officials had already tried to exercise (and failed).

So, the old Fed (meaning before the 1935 Banking Act reformed the central bank still further, which immediate led to another deflationary disaster) was amped up by new monetary powers. The Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932 amended the original Federal Reserve Act by adding a third paragraph to its thirteenth section (Section 13-3).

Departing from the real bills doctrine which had governed its earlier discounting operations, 13-3 authorized the Fed to discount any notes issued by any “individual, partnership, or corporation” that is ““indorsed or otherwise secured to the satisfaction of the Federal Reserve Bank.”

Subjected to the Crash of ’87, linking the possibility of that stock market hiccup with 1929’s, the government provoked and panicked into sending more leeway in the Fed’s direction. Though the danger to the economy was minimal, as history proved, Congress wanted the central bank to be able to bail out securities firms, too, just in case.

Senator Chris Dodd later stated his purpose here in working to broaden 13-3:

It also includes a provision I offered to give the Federal Reserve greater flexibility to respond in instances in which the overall financial system threatens to collapse. My provision allows the Fed more power to provide liquidity, by enabling it to make fully secured loans to securities firms in instances similar to the 1987 stock market crash.

The Fed didn’t know the system wasn’t in danger of collapse, so let’s give them more power in the case it ever does happen?

And so many of the alphabet soup of the ad hoc, on-the-spot invented market “rescues” of 2008, including the one made up for Bear Stearns (financing given to JP Morgan to undertake the deal), fell under the authority of this broader 13-3. Unlike 1987, the monetary system this time was at stake – and these idiots thought it was all about subprime mortgages.

The fact that authorities can’t really tell the difference when it is or isn’t should be quite alarming. For them financial problems = something to do with the Fed. Shouldn’t the Fed instead know even a little something ahead of time? You really only need such emergency measures when you’re really bad at your job.

That about sums up the difference: Alan Greenspan lucking out the eurodollar system was on his side in the eighties compared to it only beginning to stack up against Ben Bernanke. Banks, not central banks, are that difference.

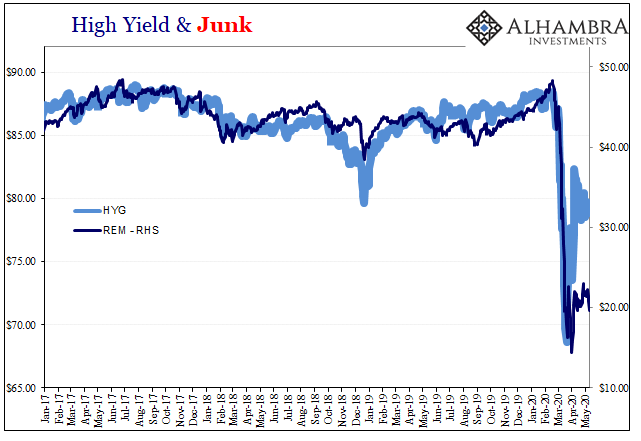

Which brings us to March 2020 when wide swaths of the corporate credit markets went totally lights out. Jay Powell’s group brought back most and maybe all (has anyone kept track?) of the 2008 abbreviations once more on the power granted under 13-3. There was one addition to the list, something called the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF).

This is what the big fuss has been about this week. Why? Because the program had been announced way back on March 23 but the Fed hadn’t bought a single asset using it until now.

And yet, magic of magic, the rout ended.

Which means, essentially, Jay Powell’s taking a(nother) premature victory lap drunk on his own presumed power of mere words and statements. He said yesterday (thanks C. Lavers):

We frankly have helped already through the announcement effect. Markets have really loosened up and started to function much better than they were just a couple of months ago at the early part of the crisis when markets were not functioning well. So we see that. And that has enabled many companies to finance themselves now. And that’s a good thing. And it may mean that we actually aren’t needed.

Because the corporate market hasn’t fallen further apart than it had during the first half of March, the Fed Chairman is claiming this is due to the financial press writing endless stories about the central bank “taking over” the bond market with purchases it hadn’t even made.

If Section 13-3, then, holds such magical properties then its mere adoption and subsequent amendments should have been sufficient. Why bother with all the hassles of buying anything when just the possibility is all it takes? As stupid as it sounds, this is what we’re being asked to believe.

I don’t know the man, of course, and it’s always a little dangerous to read someone else’s mind. But in these kinds of circumstances it isn’t all that difficult to do.

The Fed Chair is being disingenuous, extremely so. The real reason there haven’t been any purchases, leaving him to try to stake some claim on this “announcement effect”, is that the Fed wasn’t prepared until now! They’d have been buying ETF’s all this time except they just weren’t ready, having to first hire an investment consultant (BlackRock) and then go through all the bureaucratic processes to come up with a predetermined list of securities and at what amounts.

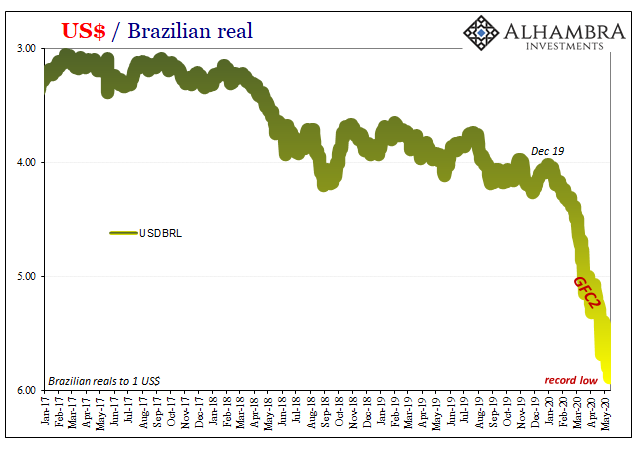

Would anything have been different if BlackRock had been retained weeks earlier and the purchases begun during GFC2? More to the point, why wasn’t BlackRock retained at least by February 20 when everything really started to turn?

We know the answer(s) because Powell’s also being coy about the condition of the marketplace right now. It stopped getting worse (right at the end of the March bottleneck) but that’s not at all the same as getting better. He’s simultaneously pumping up the level of improvement while also saying the Fed’s the reason for it.

What about the fact that this happened in the first place? Section 13-3 should be renamed for how the central bank comes in too late and celebrates way too soon. In other words, it’s March (to May) 2008 all over again.

The way you hear it told, yes, that’s what we are supposed to believe. That policymakers cutting through their own desperation finally arrived at the exact right combination of “liquidity” programs. It had to be that otherwise if the difference turned out to be instead nothing more than getting past some mid-March calendar bottleneck there’d be Hell to pay later on.

No one wanted to think about that.

In the case of 2020 and corporate bonds, the “right combination” of “liquidity” programs apparently includes a healthy dose of liquidity in the form of nothing more than an announcement. Just spoken words. Sure. Let’s bank on that, literally. Magic words are all the support any market will ever need!

The Fed’s an empty bowl; always eager to claim credit for the smallest upturns but never, ever seeing the big picture. Not in 2008; not in 1987; definitely not in the 1930’s. But 2020’s going to go just right from here? And it’s these guys who are going to make sure?

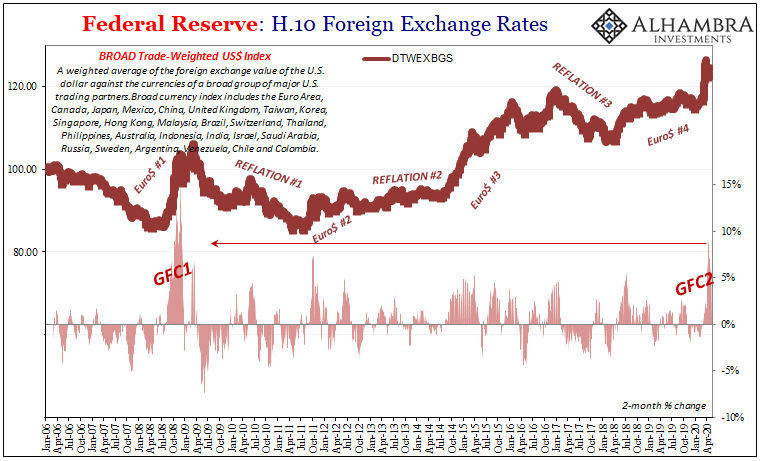

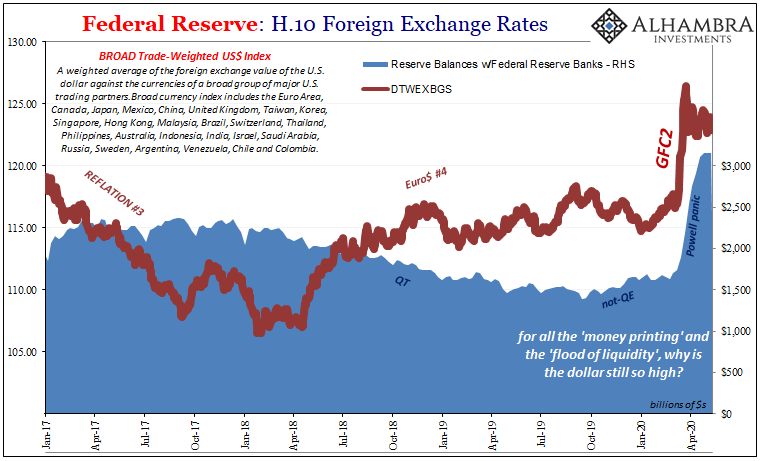

Well, Jay Powell has announced it. But who, actually, is really listening? Not nearly as many as you’re led to believe (see charts above and below).

Stay In Touch