For awhile there, a few weeks anyway, the 30-year US Treasury long bond had become the star of the mainstream show. Showered with its 15 minutes of fame, everyone loved how, for once, it seemed to agree with Jay Powell and the preferred narrative about the effectiveness of his technocracy.

The idiocy of this attention was exposed by just how little these suddenly aware Treasury market watchers had said about the thing for the several years before then.

Like the yield curve, most people only pay attention when it suits – or when its so big that it can’t be easily ignored and dismissed (like yield curve inversion). That’s a shame because the 30-year is useful for interpreting the market’s internals about a range of often paramount issues, and at other times nowhere close to inverted curves.

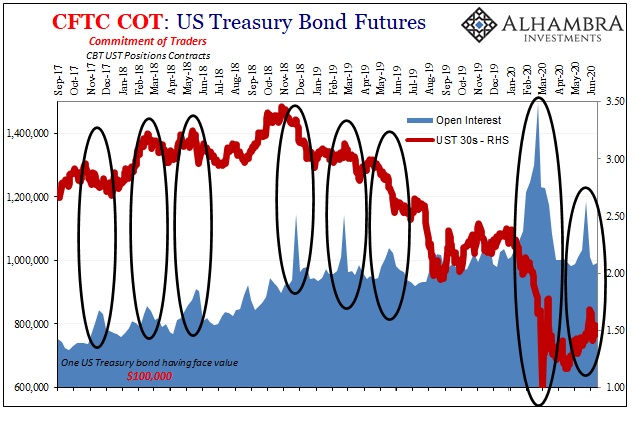

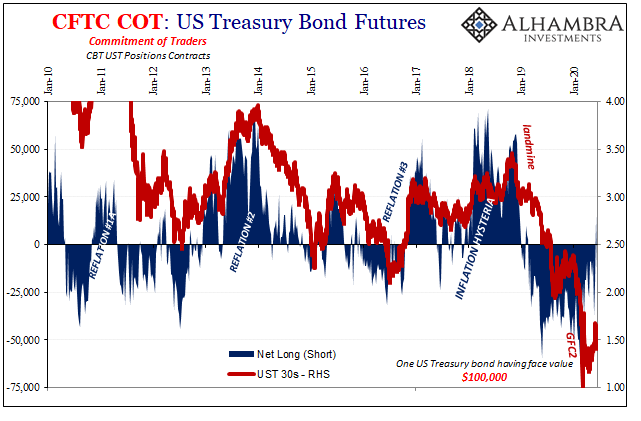

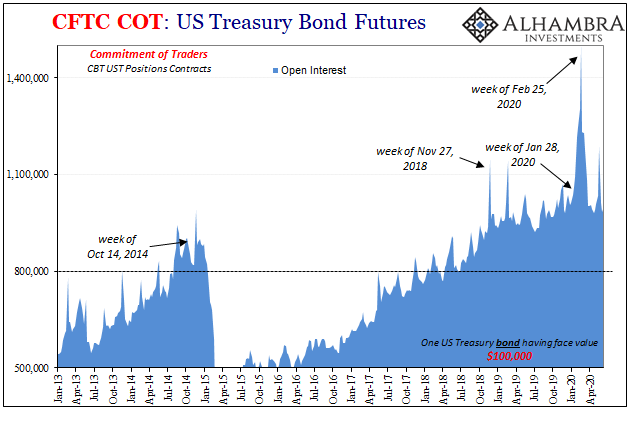

For one thing, long bond futures are extremely helpful, especially given their enviable track record (as opposed to the shameful performance of central bankers who talk at bonds rather listening to what bonds are telling them about what’s really happening on the inside). Mere open interest (OI) figures for this one category can be very, very interesting.

I explained the history years ago, back when recent 30s cheerleaders instead hated the thing for how it was ruining their preferred inflationary breakout scenario:

Compared to a lot that goes on in these kinds of markets, especially where derivatives like these are concerned, this one’s pretty simple and intuitive. Open interest goes up when markets aren’t very sure about what’s in the future. Since UST’s are the settlement product for a variety of shadow trades, especially derivative FX, what’s being hedged here isn’t really UST yields or the US government’s credit risk.

It’s not a perfect indication by any means, but whenever open interest hits above 800,000 across the Chicago platforms it’s been in the past a sign of something.

Sure enough, all throughout the last several years – even during the height of inflation hysteria in late 2017 and early 2018 – you could see the market disagreeing with first Janet Yellen and then Jay Powell about those paramount parameters. The history of long bond futures OI basically related to the instead very persistent liquidity perceptions and remaining, very real economic risks more broadly.

As I wrote back then:

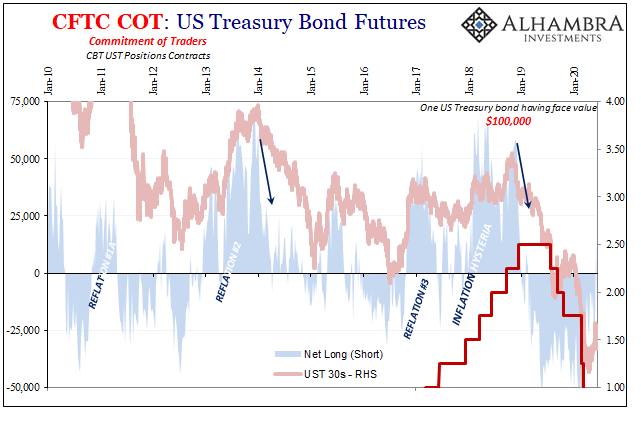

It’s a process we’ve seen repeat. In the months leading up to Bear Stearns’ ultimate demise, same pattern appears in the open interest for UST futures. There was huge demand for hedging against “some” great uncertainty that was at first palatable enough for dealers to take on, and then it wasn’t.

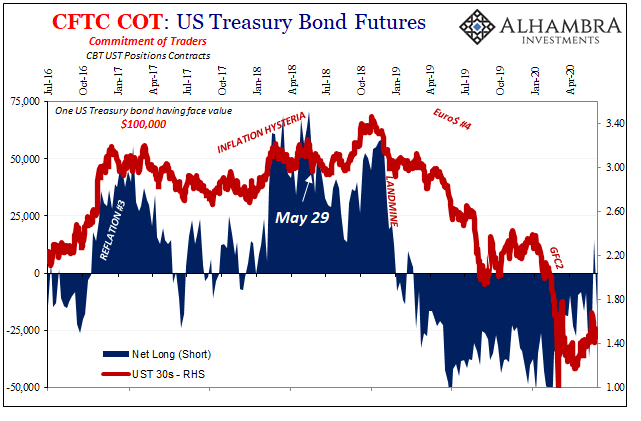

That last spike in open interest all the way on the right (above) took place while the mainstream was going on and on about the “massive” steepening in the curve, especially between the 5-year and the 30-year. Within a week, the yield curve stopped and, quite conspicuously, so did the love for the long end.

Working our way through the other pieces of the Commitment of Traders report, we find not much in the way of conviction for Jay Powell’s flood of inflation, a very curious omission. Net positions remain basically neutral and nowhere close (on the net long side) to what we would expect to find if there was widespread acceptance of a switch to even reflationary conditions.

With yields bouncing off record lows, there was, in theory, tremendous room for at least a selloff (more than the minor rebound). Instead, they remain within sight of them while markets, as I wrote above, have at best switched to neutral (after more than a year of being proven correct as to this hedging behavior).

Rather than attempt to laughably co-opt this pessimistic position via the preposterous yield caps being proposed, Jay Powell would serve the world much better and become far more effective (maybe) if he’d instead listen to what this market is saying. Try again, Jay. You’ve been led around by the bond market, futures especially, start appreciating the info and the aid no matter how much it might sting (and demonstrate to the rest of the world how irrelevant you are).

The 30-year long bond was, for only a brief moment, the object of so much affection – which showed why we’re always stuck in this predicament. The mainstream paid attention at the wrong time, rather than heeding the warning which, by more than a month (immediate above), predated GFC2 because it was inconvenient.

And then when little was going on out here, the 30s were hyped up over relatively very little – until that last inopportune spike in OI indicated something else going on at the end of May.

Like Economics, conventional commentary continues to get the bond market (therefore the monetary system and thereby the whole damn global economy) totally backwards. Some people believe this has to be a conspiracy, no one could possibly be this inept except on purpose.

No, central bankers really are that dense (see: Greenspan, Alan; series of one-year forwards) as incredible as it might otherwise seem. Several generations of the public as well as those in financial services who have little or no real training in bonds, yields, and curves – only left to what the Fed Chairman say, even when they admit they don’t know, either (see: Greenspan, Alan; conundrum).

The whole media system really is just this rigid (editorial standards demand fealty to those with pedigree, people like central bankers). Evidence simply doesn’t penetrate nor does it have any effect; we learned that much by GFC1 (subprime mortgages!) and nothing has changed so far as GFC2 has been concerned.

Instead of looking out for that inflation everyone’s talking about, look to the bond market for a badly needed dose of reality. Just be prepared for it to appear nothing like what they keep talking about in the media. Even during those very brief moments they claim to love the thing.

Stay In Touch