Foreigners are dumping their Treasuries! The Fed is monetizing the debt! The federal government has gone insane! Mass fiscal hysteria!

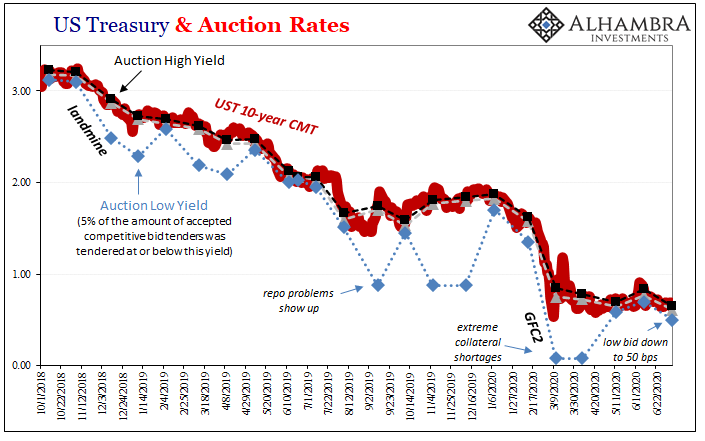

Yet, yields on these things are comfortably within sight of their record lows as prices have never been higher. Supply is very obviously off-the-charts, but so, too, must be demand. Every time we hear about “too many” Treasuries the market yet again proves it nothing more than fallacy, a myth that just won’t die.

The demand comes first. That’s the thing. So long as it does, supply can’t be an issue.

In other words, the federal government’s fiscal insanity is a secondary (if not tertiary) factor in all this. What governs the whole dynamic is that demand for the safest, most liquid instruments. And if you stop and think about it, truly and honestly think about it, then supply makes sense, too.

Why has the federal government gone crazy in the first place? To try to combat the very problem that has supercharged demand for its debt. Rather than being inconsistent or contradictory, supply and demand are, in this way, perfectly complementary.

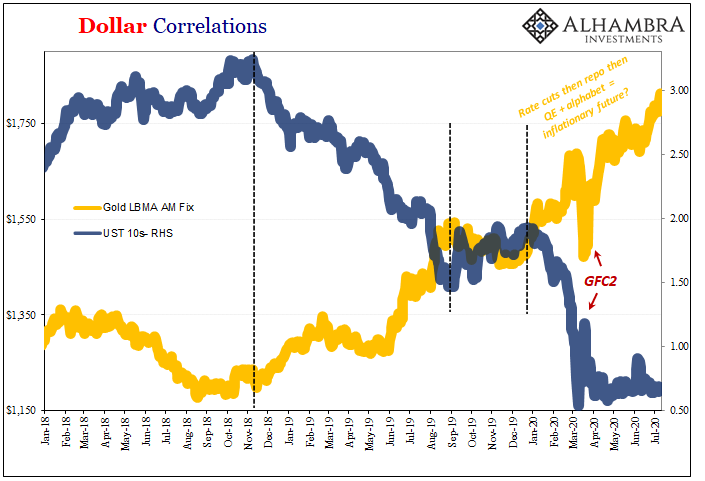

The only wrinkle, if you let it be one, is the Fed. Jay Powell sees his job as getting you to believe that he’s done an awesome job, therefore inflation must be right around the corner. The bond market, this constant demand for safe, liquid instruments, strenuously disagrees; it has the enviable track record on its side, too.

Part of his spin is his own role in these supply and demand dynamics. The Treasury market was broken back in March, he’ll say, so if it hadn’t been for the “timely” upsize in QE6 then rates would be disastrously skyrocketing right now. The Chairman will trade the current criticism over his “monetizing” the government’s debt in exchange for the implicit inflationary expectations embedded within that criticism.

Add gold to that list.

But are either of those things true? First, did the Fed actually monetize the debt? Second, does monetizing lead to inflation?

These are another set of myths which go unchallenged especially in the media. After all, if Jay Powell says it, or even just refuses to deny it, then it must be true. Even when it isn’t:

American money-market funds — a harbor for the assets of retirees and companies — have bought the brunt of the roughly $2.2 trillion in bills the government has sold to raise cash for economic stimulus amid the pandemic. The Fed has bought almost none…

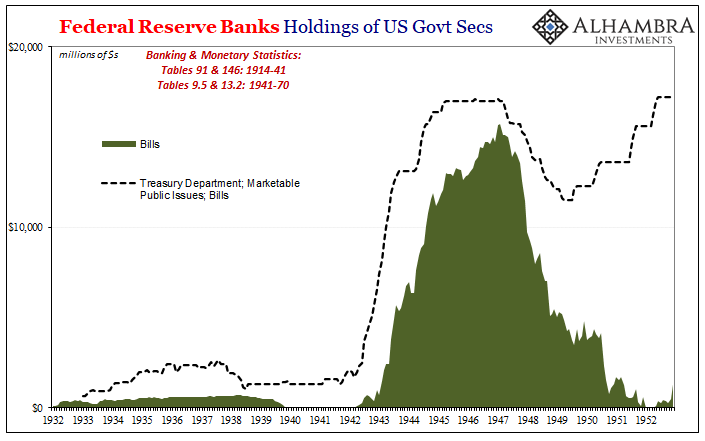

It’s the bills where most of this borrowing insanity has gotten done. Flipping the script from last year when not-QE purposefully stayed away from bond-buying (because that would signal inflationary policy) in favor of bills exclusively, QE6 has been almost entirely notes and bonds as if the Fed noticed something peculiar about that selloff in March.

While not understanding the significance, it was impossible not to notice at least the specifics:

The FOMC minutes [March 2020 meeting] just described a situation that was so bad, collateral-wise, financial participants (which we know were largely foreign official entities) were forced to sell whatever they could, including UST’s, choosing only those which were OFR. At the same time, everyone had to pile into the OTR stuff, including all the bills, because that’s all that was left as acceptable. A true funnel or bottleneck.

When even OFR UST’s are no longer as acceptable in repo, and the collateral system begins to break down along OTR and OFR lines within the UST side of that market, when the functioning collateral list gets pared down to just OTR UST’s and nothing else (I’m overstating this, but not that much), it should go without saying that this would be an enormously bad situation.

The Fed believes that it should stay out of bills because of the possibility for more of a broken Treasury market (liquidity in it) when the actual data, all the evidence says it was broken repo (collateral) further breaking down the whole global liquidity system (GFC2) since the Fed is so bad at what it supposedly does.

And in the end, the US central bank ends up doing the right thing (staying out of bills) for the wrong reasons.

That’s not inflationary. As the prices at the long end also demonstrate, with or without Powell’s QE, there’s no shortage of demand anywhere on the Treasury curve. The Chairman is picking his spots arbitrarily as if at random (or by default).

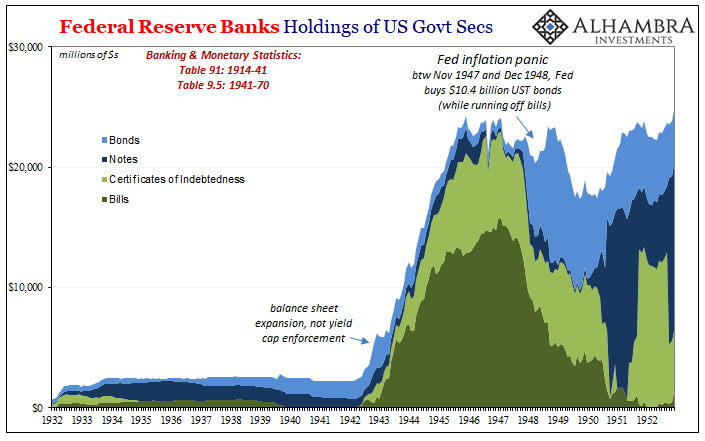

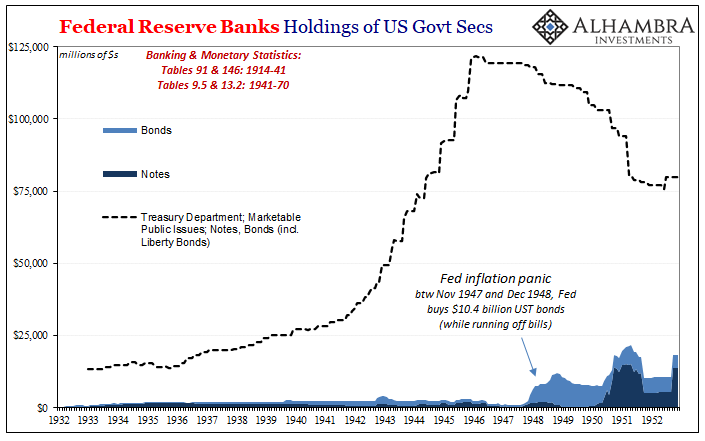

Going back to the World War II era, it was much the same (financial) situation as we find ourselves with today. In 1942, federal government deficits exploded leaving Treasury to finance it by issuing massive amounts of short-term debt – which the Fed bought by the bushelful.

Back then, it wasn’t “quantitative” but rather rate pegged. And in the end, it wasn’t much for “easing”, either.

The Federal Reserve purchased the vast majority of all the bills issued during and immediately after the war. Inflationary? Not even slightly. The reason was the same; the background behind these things continued to be deflationary (total war plus lingering depression will do that) and that’s what really mattered.

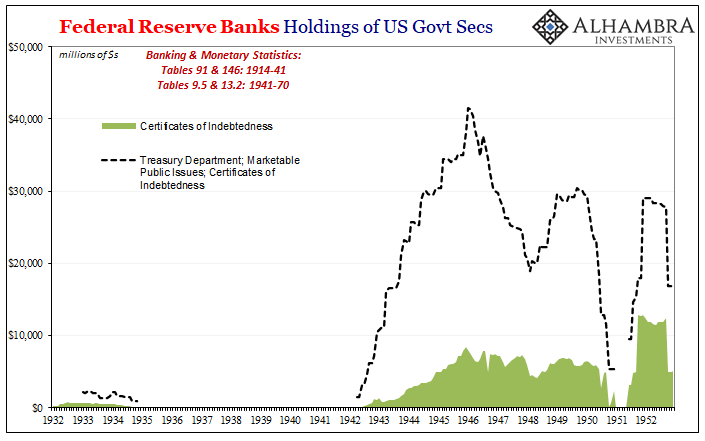

While the central bank leaned heavily in the bill market, there was no shortage of demand for other forms of Treasury debt. From certificates of indebtedness still at the short end of the curve to notes and bonds (including special Liberty Bond issues), the public snapped up what was back then an even larger expansion of the government’s reach (by proportion).

Like the 1947-48 bond buying episode (the Fed’s inflation panic), we’re supposed to believe that the central bank played the pivotal role in keeping the financial situation orderly, trading off that priority by risking an inflationary breakout. Bullshit. That’s the myth that has been conjured, hardly in keeping with the reality of the situation.

Sure, the Fed monetized the bills during WWII, but so what? The depressionary conditions rampant throughout the markets and economy led the private system to easily monetize everything else, the vast majority. Even the Fed’s inflation panic in bond buying was a tiny drop in the bucket.

Yields said so.

Like today, the Federal Reserve’s role was limited to projecting stability – even when it wasn’t really needed. But because you can’t observe the private market’s unstoppable demand, you’re left only with the Fed’s balance sheet and the impression that it is impressive when it really isn’t.

Back then, the Fed bought all the bills and almost nothing else. Today, the Fed buys some bonds and hardly any bills. In both cases, the American people were and are led to believe this was and is inflationary (especially in 1947). Balance sheet expansion like this could be, but only under the right circumstances.

The low yields are your clue. The Fed is a bystander, not a powerful, central agent to dictate terms. That especially goes for what happened in March 2020, the mess in repo/T-bills a perfect example of how today’s officials have no idea what they are doing. They just do things and let the financial media write them up as wise and meaningful, as if monetary policy is the only thing that matters.

It’s not that there is huge, persistent, unquenchable demand for the safest, most liquid assets around, it’s why there is such demand in the first place (shadow money destruction you don’t see). When you realize the central bank isn’t central and doesn’t do much as far as actual liquidity, such demand makes perfect sense. Therefore, so, too, does supply.

When the bucket is full of holes (deflationary background) adding a little bit of bank reserves won’t ever fill it up, let alone overflow (inflation) the thing. But you can understand why monetary authorities would try to make it seem like what they are pouring in to the leaky pail (the monetary system) is the only thing that you should factor. They really believe that if you believe in them belief is all it takes to cork the holes.

History conclusively demonstrates you need more than a puppet show to plug real holes. And that’s just another way of writing the interest rate fallacy.

Stay In Touch