On December 3, 2015, Europe’s central bank, the ECB, supposedly disappointed markets especially those trading European equities. Losses were large because Mario Draghi’s gang of policymakers merely extended its first QE rather than accelerating the pace of purchases. Investors, such as they were, had been told to expect more than that.

To make matters worse, according to the mainstream narrative, the central bank also chose to take it easy on the banking sector. The money rate floor, the ECB’s deposit rate, was reduced but only by 10 bps, making NIRP only a little more NIRP-y at -30 bps. It had been hoped officials would take a more “accommodative” stance with “money printing” first and then being more aggressive in punishing the banking sector until it did more lending with said “money.”

None of those things were true, of course, but for the puppet’s show audience who all buy tickets based on the unbreakable myth the central bank actually matters, it all sounded disappointingly splendid.

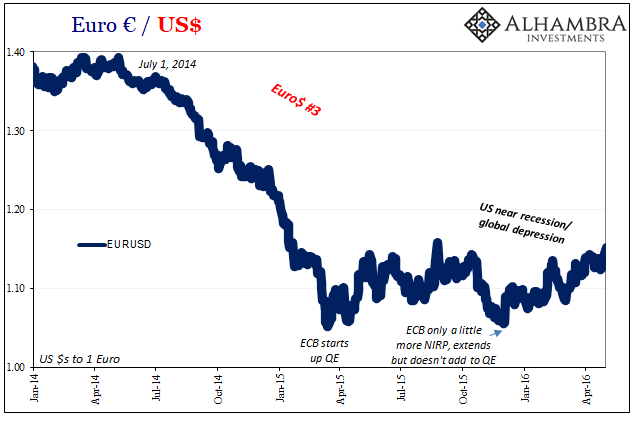

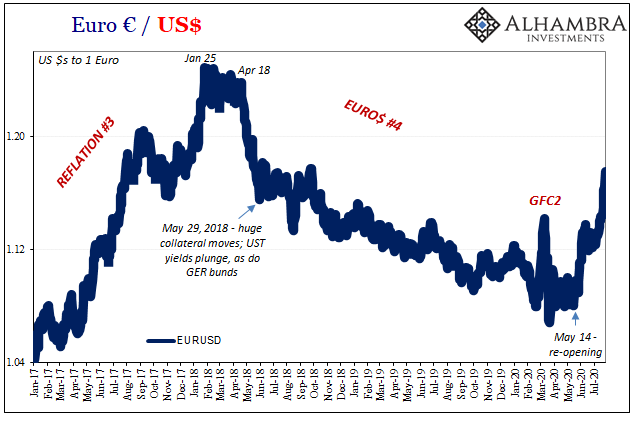

It didn’t really seem so bad at least where Europe’s currency had been concerned. The euro began a rally on that December day which ended up lasting for months. A rising euro is, allegedly, a positive risk-on signal that obviously corresponds on the other side of the ledger to the more commonly pleasing falling dollar.

And yet, that’s not how it went. Globally, anyway, December 2015 and January, February 2016 were some of the worst months since 2008-09. Market upheaval was widespread consistent with the funding, liquidity mechanisms that make the dollar rise more broadly even if it had been falling against the euro. The global economy, especially as it related to emerging markets, was absolutely pummeled leaving no doubt as to which kind of active dollar condition was in effect regardless of whatever direction the euro might have taken.

As you’ll also note on the chart above, this wasn’t even the first time during that particular year when this sort of backward paradigm had been spotted. In March 2015, coincident to the ECB launching its first (of several) QE, the euro had risen then with the dollar falling against it throughout most of the year even though, again, a global dollar shortage was unmistakable – the stuff behind a rising dollar.

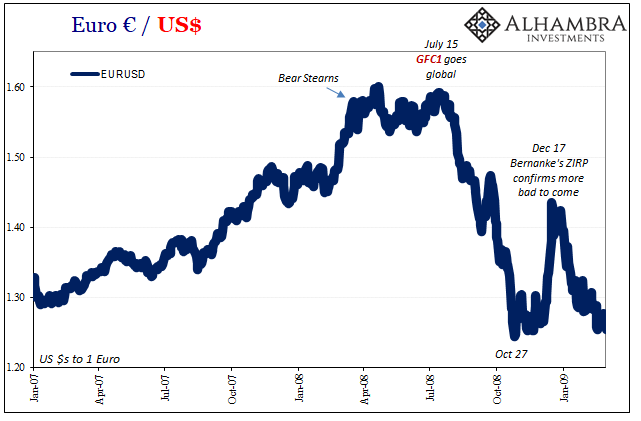

Dating back to the first global dollar shortage in 2008 and 2009, you’ll find a few more instances where the European common currency defied these general impressions. On several key occasions, a rebounding euro had been premature to the eventual resolution to the otherwise still-rising dollar system (just not against the euro).

Back in 2008, at the end of October (as the Fed unleashed its commercial paper program which was consistent with the dollar shortage growing worse and moving onward to devastate non-financial markets, too), the euro would stabilize after tanking since July consistent with that background.

It had then surged higher early in December 2008 on hopes GFC1 had finally run its course, only to be flattened once more while ZIRP in the US was announced confirming that even Bernanke understood he’d failed to contain the contagion which continued to rage – a rising dollar trend which wouldn’t fully exhaust itself until March 2009.

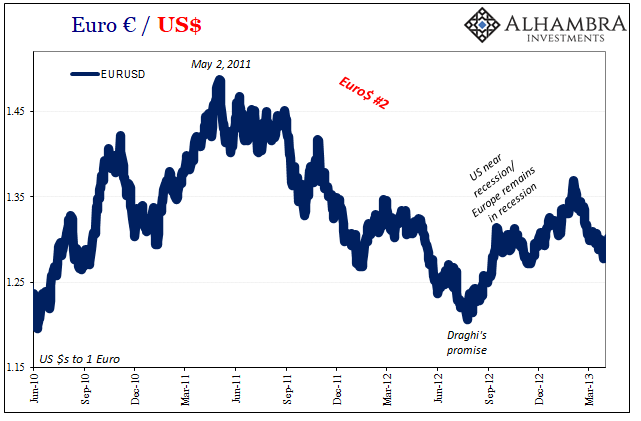

A few years later on, during 2011-12’s devastating shortage (Euro$ #2), one that hit Europe particularly hard, once again the euro rallies on something some central bank did (Draghi’s promise, in that case) premature to the actual end of the actual rising dollar baseline behind it all.

Like Euro$ #3, the euro was moving higher during the worst of this one, too. Maybe that means early to some people, getting in on reflation months before such a thing is even possible, but realistically it’s a nod to the euro as not being particularly helpful providing clarity during these situations.

The initial downtrend in the European currency certainly is, as it is always consistent with the rising dollar “stuff” we typically find across more than just currency exchange rates, but then once the eurodollar squeeze takes hold something else takes hold of the specific dollar to euro translation.

It becomes susceptible to “stimulus” interference; not actual stimulative measures, of course, but perceptions of one central bank (or fiscal government) doing something that could, in theory, positively impact Europe – even if there’s no real effect in all the rest of the vastly more important dollar shortage, rising dollar “stuff.”

There’s no real consistency to it, either. At the back end of Euro$ #3, for example, you could argue the higher euro was Europe’s system being largely left out of the rising dollar/dollar shortage wrecking most everything, real and financial, everywhere else.

But during those countermoves in Euro$ #1 and then again in Euro$ #2, this certainly hadn’t been the case; GFC1 arguably trampled Europe’s economy worse than the US economy, as it inarguably did in the back half of #2 in 2012, Draghi’s promise notwithstanding.

In other words, late-eurodollar squeeze rallies in the European currency against the dollar has yet to signal a meaningful change in the dollar’s otherwise jumpy and destructively rising tendency. It’s a canard.

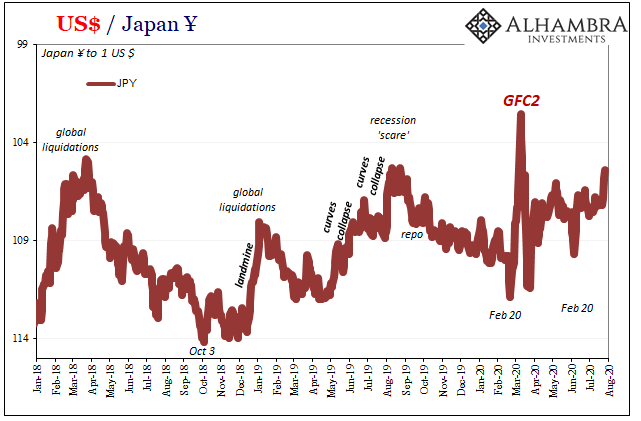

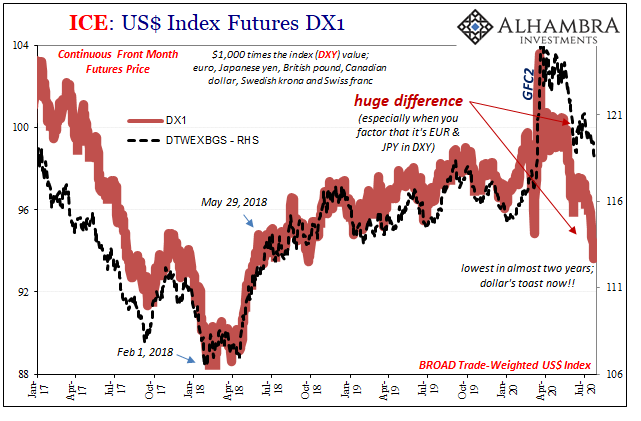

That’s one reason to look upon the current wave of “dollar destruction” guarantees being promulgated widely right now predicated on the DXY dollar index with grave suspicion. This specific view of the dollar is, at times like these, unduly influenced by EUR – as well as the backward convention for JPY.

Opposing the common perception of an upward bound euro, a rising yen is actually really bad news, so we’re already starting off in confusing fashion. Combine the two, upward moves in JPY and EUR, and while DXY is being pummeled there’s not much “weak dollar” to infer from that index’s downturn. On the contrary, you’ve got the often mis-moved euro which, as shown above, falsely signals risk-on while at the same time the “strong” yen which most often correlates to the rising dollar “stuff” of risk-off.

Over the last couple trading session here in the GFC2 era of July 2020, JPY has broken out of its recent range in the “weak” dollar direction that instead indicates more of the same rising dollar background. Add in the post-COVID re-opening euro, and it’s a recipe for reading into DXY what’s not actually contained in its movement.

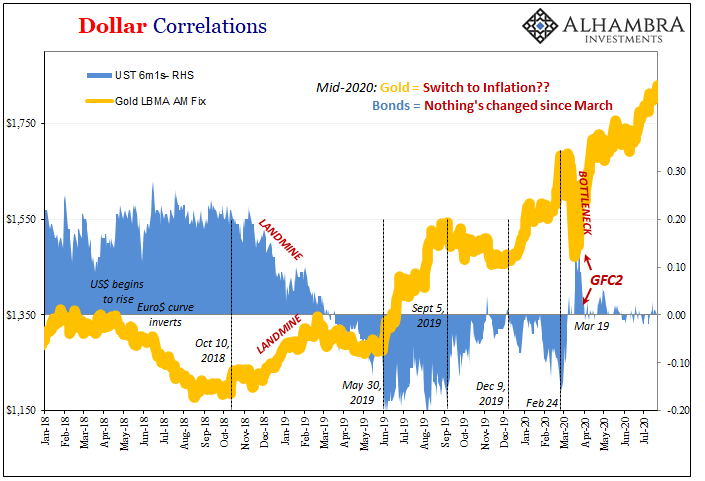

The dollar’s going down! Yes, against the euro (doesn’t mean much) as well as the yen (which actually means the same thing as when the dollar’s up against everyone else). Then you add to this mix gold’s remarkable run of late, which convention also interprets in the same backward fashion, and, oh boy, so much mainstream projections of certainty predicated instead on an entire ocean of gross confusion.

It’s enough to make Jay Powell and Christine Lagarde smile. And that’s as far as this “good” news goes.

A broader dollar index such as the Trade-Weighted one suggests that things haven’t really changed much at all since late February. Down a bit since the peak, but still remarkably high and dangerous in true post-GFC fashion.

Huge difference (below). But since “money printing” and the Fed’s inflationary objective (along with dollar and Treasury bears) are mainstream goals, you’ll only hear about the one so long as it continues on this track – just like you once had recently with the 5s30s that you don’t hear about anymore, that piece of the curve now conspicuously absent from this very discussion.

If the bond market and curves were actually moving in the same way to corroborate DXY, then there’d be something to this (and more likely just mild, 2017-style reflation than this hyped up nonsense). Instead, bonds and curves look very much like continued rising or high dollar stuff far better demonstrated by this other trade-weighted index.

Stay In Touch