Why the big deal about the Fed’s new grand strategy? For one thing, as noted yesterday, there’s that whole lost decade which policymakers finally have acknowledged. They’ve quite a lot of catching up to do, but have waited for the most inopportune moment to…basically do more of the same things that hadn’t accomplished anything other than lose an entire decade.

Already questions and it hasn’t even begun. The urgency of today is plainly obvious. You start out with a decade’s worth of a hole and then enlarge it with a March 2020.

Why is the Fed so intent upon increasing inflation when so many Americans (and others around the world who depend on dollars) are hurting so badly? Powell in his virtual Jackson Hole appearance spent virtually more time on trying to explain this than he did explaining what was being done to accomplish the task.

It’s not really about inflation and consumer prices. Those would be the symptoms of success, meaning actual economic growth. A booming economy throws off some price pressures which are easily absorbed and “paid for” (redistributed) by that booming economy. Faced with the choice between another lost decade of disinflation, or actual growth with high levels of inflation, you’d be foolish not to sign up for the latter.

The question, the only question, is whether the Fed can actually do it – can they reignite the economy via some, any, inflationary channel? The last decade, the very reason behind the central bank’s grand strategy review, says, literally, not to bet on it (and now you know bond yields; they’re just that simple).

In our latest podcast (the first segment to be published on Monday), my co-host Emil Kalinowski and I go through the ultimate guiding principle behind all this mess; including this Jackson Hole Strategy Update (for lack of a more useful description; A Central Bankers’ Guide To Losing Two Decades, perhaps?)

It all comes down to a single phrase, one first constructed by Paul Krugman in 1999: credibly promise to be irresponsible. Its meaning may not be quite what you think, though you’ll have to wait for the podcast to hear about why and how this two-decade old expression is the basis behind average inflation targeting (or 2018’s symmetry) as well as increasingly bizarre thoughts on future QE’s.

For now, understand that Jay Powell’s under doubly intense pressure to get this inflation thing started. The clearest path to more recession under these conditions is for American consumers to further tune out his inflation-mongering.

Monetary policy under an expectations-based regime believes in the power of signals; the Fed says it’s going to be printing a lot of money (actually, the Fed never comes out and says this because those working at the Fed understand this doesn’t happen, it’s the financial media who say this on behalf of the Fed to which the Fed is ever-grateful for not being caught out in a blatant lie; well, most of the time) which is supposed to lead consumers (as well as employers, business leaders, and market participants) to get to work today front-running the consequences.

If you think the Fed’s going to be irresponsible, and irresponsible money always leads to inflation, then right now you better start buying goods and services before their prices start going up. The central bank has induced you to undertake economic activity you wouldn’t have otherwise – because its Economists (using econometric models) assume a whole bunch of things that lead them to believe this is a much better outcome for everyone.

As you and all your neighbors spend more today getting ahead of the promised inflationary wave, the faster the economy roars back to life fulfilling this overriding expectation; the more consumers spend, the more businesses have to hire (back) workers to keep up, leading to more spending and more hiring. The virtuous circle.

But what if consumers don’t believe the inflation story? What if they believe it, maybe, but can’t do much about it?

If you’re Jay Powell and this is your brilliant plan (which, again, is basically the same old plan which lost the world economy an entire decade it couldn’t afford; see: flaming cities), then any serious lag in consumer spending puts a huge dent in it; puts a complete stop to it, really.

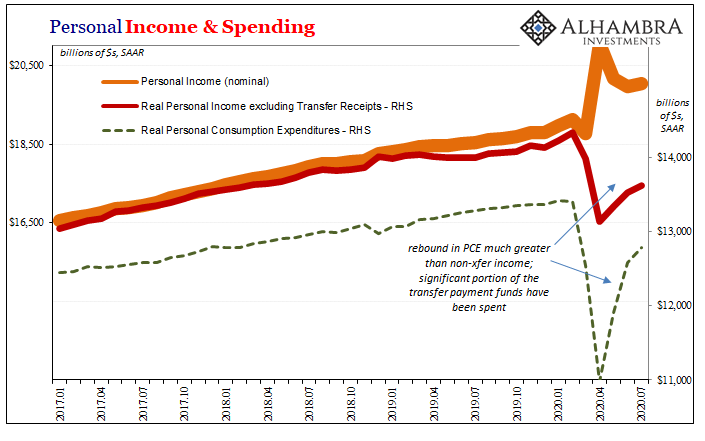

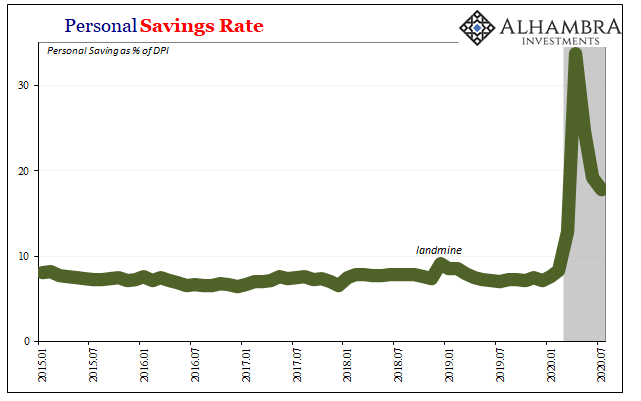

The latest monthly income and spending data (July 2020) from the Bureau of Economic Activity (BEA; the government folks who do the GDP tabulating) shows that Americans have cash but are not spending in the way Powell needs them. The savings rate remains ridiculously high because of government transfer payments, because otherwise outlays continue well below the prior peak despite this.

Private income, i.e., the labor market, continues to lag seriously behind. Therefore, consumer behavior is no mystery. Jay is trying to convince them there’s inflation coming, and while many might believe him, they’re clearly more concerned about the real state of the labor market and refusing to act.

If you think the prices of goods and services are going to rise at the same time you perceive real uncertainty about your job situation, it may not matter one bit the first part because you’ll focus your spending habits exclusively on the second; save for the real possibility you don’t have any income, rather than spend for inflation they always promise but never shows up (why inflation expectations in markets and surveys is at and near lows).

The uncertainty in the labor market isn’t difficult to understand, either. I’ve written about the possibility employers hadn’t actually fired near enough workers during the non-economic dislocation (shutdown). And that makes sense, too; if you think the economy’s only temporarily closed and that it will open back up soon putting everyone right back on their feet quickly, keeping a few idle workers on the books during the worst of it would seem the prudent option.

Better to be up and ready for the reopening flood than have to scramble at the last minute and risk missing out.

The problem with doing so is, what if there isn’t the level of reopening flood everyone had been made to anticipate? Then those idle workers become a drag as revenue, and therefore required work, continues to lag even as more and more is reopened.

But can we find some evidence for this idle-now-increasingly-costly labor “reserve?” Anecdotally, stories abound of paid furloughs and businesses (not just airlines) pleading for help before they’re forced to undertake a second round of layoffs.

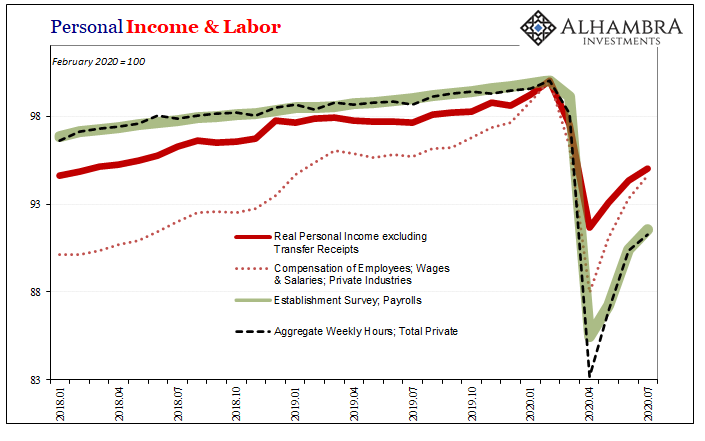

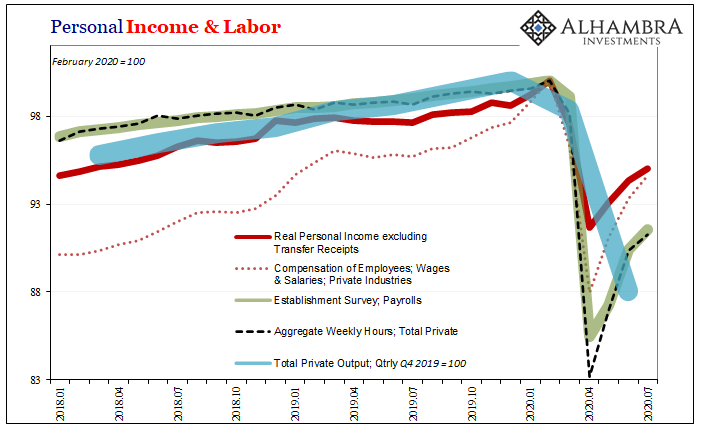

I think yes, there is data – though it needs to be qualified. I’ve committed a few no-no’s by splicing together different data series and trying to normalize them with each other so as to come close to comparing apples-to-apples. The purpose isn’t to prove this idea of a labor reserve, which isn’t going to be possible, rather to simply see if this rough comparison even takes that sort of shape – meaning it hasn’t been completely ruled out.

What we find is what we would expect to find; the aggregate (private) level of pay fell significantly less than the aggregate number of (private) payrolls, the decline in which was substantially less than aggregate (private) hours. Idle workers working fewer hours while still getting paid, basically.

And then on top, total aggregate (private) output even lower still, suggesting businesses were intentionally cutting into short run profits by keeping in reserve these idle workers. In terms of the data, it’s at least in the right order and takes that kind of shape.

These may not look like huge therefore significant gaps, but in the context of even the nastier recessions a 1% or 2% margin like these is all it really takes.

Again, all sorts of caveats must be applied; the income data is skewed upward by the fact layoffs tilted heavily toward lower income jobs; the output numbers are quarterly rather than monthly, meaning that we can only extrapolate what these might have been under like terms (all monthly, or all quarterly); hours are biased by the differences between full-time and part-time which don’t get broken down in the Establishment Survey. And so on.

As I wrote above, these figures don’t prove anything. Our goal here was mainly to see if there was at least some minimal validity behind the idea so as to begin explaining something that is absolutely happening, and doesn’t seem to want to stop:

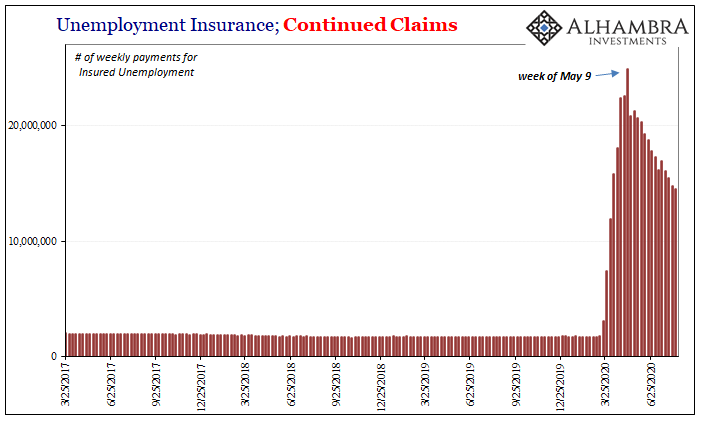

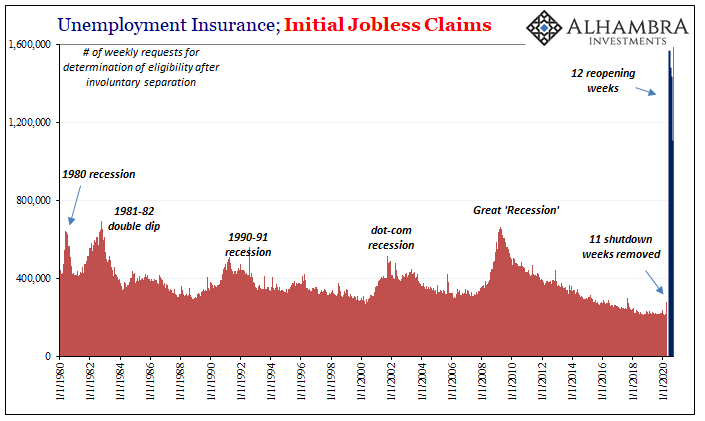

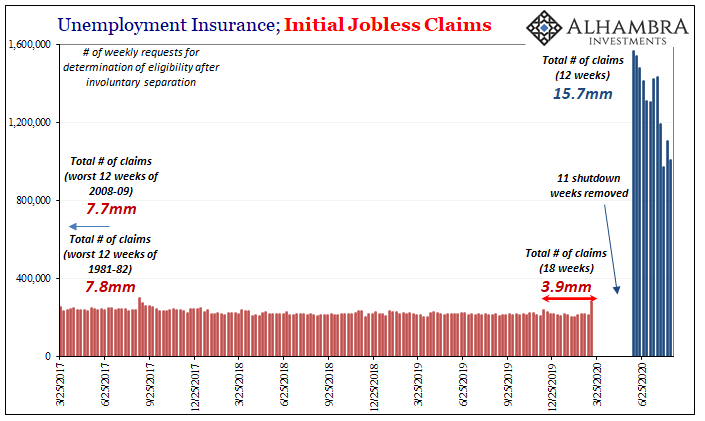

For reasons that aren’t fully apparent (yet), the labor market is being decimated to a degree we’ve never seen before in modern times. There has to be something serious going on, and this isn’t shutdowns, pauses in reopening, nor social distancing.

It’s pure deflationary economics (small “e”).

And it would explain the spending and saving figures quite easily. Consumers fear this sort of labor market, the destructive sort, far more than they might theoretically fear Jay Powell talking about average inflation targets after a lost decade spent being unable to meet any of them. For all the modern complications, and the modern belief in all things central bank, really simple stuff.

With preliminary data on sentiment for August, business and consumer, it would put an exclamation behind the urgency of Jay Powell’s (absurd) performance (and the media’s overhyping what really was the same policy as implemented in May 2018). It doesn’t matter that more inflation is bad, this other is worse. Way worse.

Stay In Touch