Bill Dudley was a key guy at the Fed for a very long time. It is very important to point this out. Not only did he hold two of the central bank’s most crucial positions, he held them during the institution’s most critical moments.

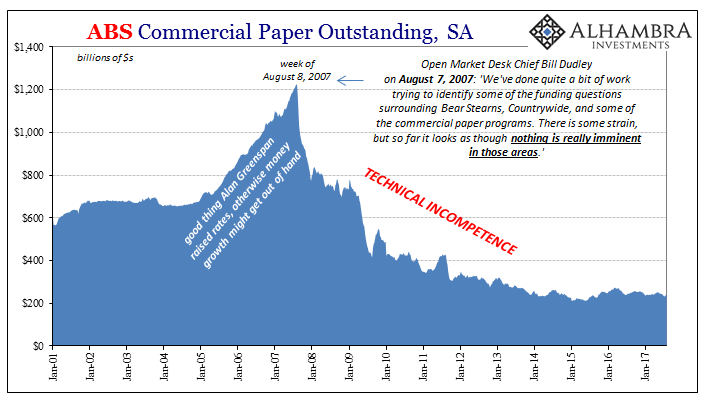

Dudley was Manager of the system’s Open Market Account in August 2007. On the seventh of that particular month, as Desk manager, Bill relayed to the assembled Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) members and their gargantuan staff how “nothing is really imminent” in the area of subprime and specifically commercial paper.

Two days later, on August 9, the entire commercial paper market began to collapse. It still hasn’t recovered.

In October 2008, as the worst of GFC1 was setting alight the world all around, still at the Open Market Desk, Bill Dudley bragged to the FOMC how IOER would put a floor under the fed funds rate which had been too low at the time. A floor was needed, Dudley reasoned, because this would help relax the devastating crisis conditions. IOER did no such thing, of course, and as the crisis only worsened the fed funds rate sank even lower (how’s that for an interest rate fallacy!)

These were no small things and I could actually go on and on with poor Bill. In time, Dudley himself would go on after all these major failures, failing himself upstairs to the top job at FRBNY (where the Open Market Desk is operated) – you see what I mean about the Fed. You might even begin to get the impression these people don’t seem to know much about how the monetary system actually works.

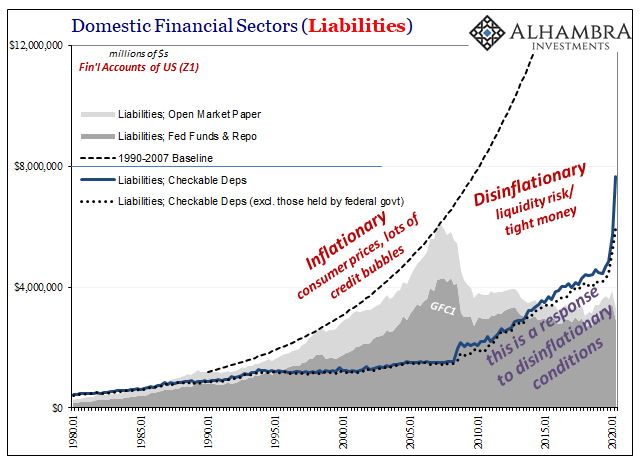

The story of his time in that place was the QE story; the Open Market Desk doing most of the QE work. Trillions in bank reserves were created under his watch which was, many people kept saying, money printing. Nope. Nor sir.

As I’ve pointed out many, many times, if you actually ask a central banker this question directly, they will admit to you it’s not (though you’d probably have to point a gun at one to get them to answer the question honestly and directly). QE isn’t money printing.

But if it’s not money printing, what the hell is it?

There’s a ton of academic literature on this very topic. And in terms of describing what QE is supposed to do – not money printing – it’s incredibly straight-forward. Does it work? The Economists do their absolute best to stretch the meaning of “work” and even then their results are at most inconclusive.

Before getting to those, first what QE actually is: just two things (again, neither one is money printing). By removing largely riskless assets from the hands of the banking system, monetary officials hope those same banks will by choice or lack of other options replace those assets with risky securities or, best, lending into the real economy.

This is called rebalancing, or portfolio effects.

The second reality of QE is…purposeful use of the myth of money printing. Economists and central bankers don’t call it lying, obviously, instead this is branded as signaling. And with QE, as opposed to something like simple rate cuts, there is the byproduct of bank reserves which aids in the lying (I mean signal).

Understanding its two, and only two, channels, let’s go back to Bill Dudley this time in January 2014 for his assessment of QE’s performance to that point:

We don’t understand fully how large-scale asset purchase programs work to ease financial market conditions, there’s still a lot of debate …Is it the effect of the purchases on the portfolios of private investors, or alternatively is the major channel one of signaling?”

Since there had been four of them by then, two still ongoing, the fact that Dudley, of all people, couldn’t say with any sort of certainty should have been a huge red flag. Four QE’s in, and they still don’t really know? This was, after all, the guy who had always said the Fed’s things always work.

There has never been a more confident man in Federal Reserve policies than Bill Dudley. How do you think the guy really got himself promoted all those times?

There was also a third option for evaluating QE, though – the real reason no one, not just Dudley, could say much definitive about effectiveness was because it doesn’t work at all through either channel. Bigger things and all that.

But what would have been bigger than four massive Fed QE’s (and, as noted earlier this week, an overgrowth of checkable deposits in the commercial banking system seemingly accompanying them)?

At the very same time Bill Dudley was uncertain about the lack of portfolio rebalancing (just as the Japanese had warned) as well as wondering how a fairy tale spun around bank reserves might not be able to resolve a real-world money shortage, there began an outbreak of, you know, real-world money shortage. In dollars.

Furthermore, its main target seemed to be China. But since monetary understanding was, and remains, so primitive, at that moment while the world fixated on worthless QE’s and the legends spun about them, what was happening real-world dollar-wise to the Chinese was totally incomprehensible.

A bedrock assumption had always been made about CNY forever rising. Here it was falling. And it would go on to fall further, and further, and further. No one could make any sense of it – thanks, in large part, to mistaken assumptions about QE and the real role of bank reserves.

I wrote just two months after Dudley, in March 2014:

What all this data shows, as opposed to conjecture about the supernatural powers of central banks, is that yuan’s devaluation may be directly tied to dollar shortages. In fact, as I argue here, it is far more plausible that a dollar shortage (showing up as a rising dollar, or depreciating yuan) is forcing the PBOC to allow a wider band in order that Chinese banks can more “aggressively” obtain dollars they desperately need. Worse than that, the PBOC itself cannot meet that need with its own “reserve” actions without further upsetting the entire fragile system.

That passage, however, only makes sense once you properly understand QE isn’t money printing – just as Bill Dudley was struggling to understand why, for yet another time, the Fed’s genius lying, I mean “signaling”, wasn’t producing the predicted, intended results.

Far from the end of the story, even the Chinese version of it, early 2014 and CNY only began to raise more questions and spawn more terrifying consequences. Forget QE altogether, why would dollars suddenly become scarce for Chinese hands? Where did China get those dollars in the first place?

Questions no central banker even knows – to this day – should be asked.

During this same period, financial circles used to talk about something called the “yen carry trade.” It was so common that like QE it was accepted without challenging any of its premises.

The mainstream version had been this: because there was so much yen due to the Bank of Japan’s efforts, foreigners could borrow yen cheaply in Japan and then convert into dollars in order to purchase much higher yielding assets. In the conventional telling, this indicated that interest rate differentials, and perceptions about them in the future, therefore would explain at least JPY’s movements.

Always a small kernel of truth in these things, in terms of this carry trade there had been more truth than not for once. Just one key difference. I wrote all the way back in 2015:

Finally, there was the largest yen “safety” bid so far, a huge spike that began August 19 as the “dollar” system was run further toward its ultimate global liquidation point. Was that the carry trade unwinding? Most assuredly, but not for or of itself and certainly not because of factors in Japan. In other words, in these specific episodes at least, the carry trade was likely just one method of expressing broader uncertainty and then fear against US assets. To my view, that is an enormous statement itself given the rather deserved disdain for the yen.

This was August 2015, which you might remember was likely the first month anyone had ever paid much attention to China’s currency; the monster CNY “devaluation” which stunned a world unable to adequately characterize, let alone explain, it.

So, if the common view of the yen carry trade was incomplete, what was the real thing? What was the crucial difference which might also explain QE’s impotence, China’s falling currency, and Japan’s rising? Where are the dollars in all this?

From 2017:

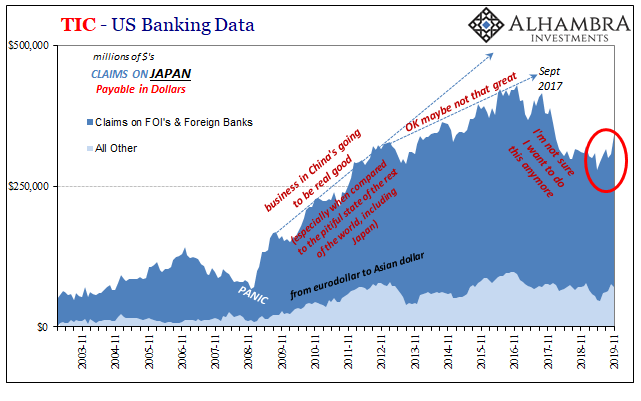

Yet, the carry trade is vastly more dynamic, therefore matching more closely the real world not limited to the need for simple regressions. Japanese banks have yen; all the yen they could ever need or want. Like bank reserves in the US, those created by the BoJ in its various QE’s do nothing but sit idle, as do the newest reserves now penalized by NIRP over the past year. Structurally, then, Japanese banks are the one side of the carry trade being short “dollars.” They are so because the world needs “dollars” and they need Japanese banks to redistribute them (how they obtained is another question entirely, and one that stretches back with a rich and complex history to the very origins of the eurodollar system; in short, a digression best left for another day).

The carry trade was never foreigners borrowing yen and then swapping into dollar assets, it was Japanese banks putting up yen reserves (an asset) as well as ST JGB’s as collateral against mostly basis and currency swaps in order to then redistribute dollars across Asia and, you know what’s coming, China.

Back to March 2017:

Of late, the need for “dollars” has meant China as the Chinese need as many if not more than anyone else. China’s economic “miracle” was financed by them, and to some unknown but surely high degree via Japan. The “rising dollar”, which is euphemism for a “dollar shortage” which is itself a symptom of systemic instability, has robbed a great many places of flexible and fluid “dollar” flow.

If CNY is falling, that’s dollar shortage for China. And if there’s a dollar shortage for China, then you can (literally) bet Japan’s in the middle. How can you literally bet? Here’s what I wrote in 2016:

The negative yen basis swap acts like leverage where even yields on the interim “investment” are negative. Any speculator or bank with spare “dollars” could lend them in a yen basis swap meaning an exchange into yen. Because you end up with yen you are forced into some really bad investment choices such as slightly negative 5-year government bonds, but that is just part of the cost of keeping risk on your yen side low. Instead, the real money is made in the basis swap itself since it now trades so highly negative. The very fact of that basis swap spread means a huge premium on spare dollars; which is another way of saying there is a “dollar” shortage.

And since that massively profitable negative basis lasted month after month after month (at times for years on end), chronic dollar shortage. Even with so many QE’s.

That’s why you could make a fortune in basis swaps against the yen; Japanese banks had created for themselves an enormous synthetic dollar short position which linked them closely to conditions in China.

If questions were suddenly raised about China, as they had been from early 2012, growing more serious by late 2013, then Japanese banks’ exposure becomes fair (eurodollar) game. And once it becomes so expensive to keep funding the real yen carry trade, there becomes so much less of the real yen carry trade. Bad for Japan, worse for China.

And nothing good for the eurodollar system as a whole, the global economy suffers another squeeze of its hidden, shadow monetary noose.

My intended point in going through this long review exercise is this: while the world was told to fixate on QE’s and bank reserves like they were some magic elixir, for reasons no one could adequately explain, all this other stuff had been going on in the shadows causing all kinds of real world consequences that regular folks (and even most “experts”) could never come to understand.

What QE and bank reserves had really done, in many ways, they had elongated these shadows of monetary ignorance.

But today we are going to end on a more positive note. Here it is:

The Japanese government bond market is rarely considered interesting. With yields literally pinned at zero, and trading practically nonexistent, it has limited appeal for discussion even among the most cerebral international investors.

But beneath the placid surface, the trade in short-term Japanese government bills and deposits conceals a thriving world of dollar funding, which offers hints about developments in China’s banking system too.

From today’s Wall Street Journal, the yen carry trade – the real one! – finds some badly needed mainstream light. I won’t even linger on how the article says this process is “thriving”; no, I’ll instead report what really is a solid sign of progress. Baby steps, for sure, illumination nonetheless.

Building upon our work about bank reserves this week, the overriding message is simply this: this monetary system is far, far more complex than you’ve ever been led to believe. QE, and bank reserves, was designed instead to keep you in the dark, to make everything seem so easy and simple simply because central bankers are just as much in the dark about money as you are (were?) Bill Dudley, sadly, was no outlier.

Understanding and appreciating these complexities, even just witnessing their contours, as we are doing here, this is an important broad step toward being able to understand what’s really going on. In small ways like the real yen carry trade as well as much bigger stuff like CNY, thirteen years of no global growth, and all the social political consequences.

More light, not less.

Bank reserves aren’t money – and they aren’t neutral, either. In this context, and what it has meant for global developments across more than a half a decade of recent history, bank reserves might only be classified as anti-money for how they aim to destroy curiosity about how this modern eurodollar system actually does work, especially these more frequent times when it doesn’t.

Stay In Touch