Mario Draghi was a very polarizing figure for him to be atop a central bank that has no natural constituency. Sure, there is a European Central Bank but there remain National Central Banks which had retained their own powers and influence following the monetary union. Draghi’s approach rubbed critics the wrong way, a growing legion of them, a lot of times because he simply refused to talk with anyone.

Mario would often run to the press to announce his position before even consulting the ECB’s Governing Council.

Christine Lagarde was hired to replace him largely because she was a politician who did what politicians do (effectiveness, nope, that isn’t part of the job). She negotiates and seeks consensus no matter how ill-suited the negotiated consensus. So long as everyone gets along, great.

Even Lagarde’s first major policy blunder hadn’t blunted her congenial reputation. Immediately following it was COVID which for a time, as happens during big crises, brought a spirit of unity and togetherness. At least that’s what was mostly reported. We’re all in this together, everyone keeps saying from their lofty perches of special privileges free from accountability.

That’s over now, though, as the old dividing lines have reappeared. Why? The same reason as always.

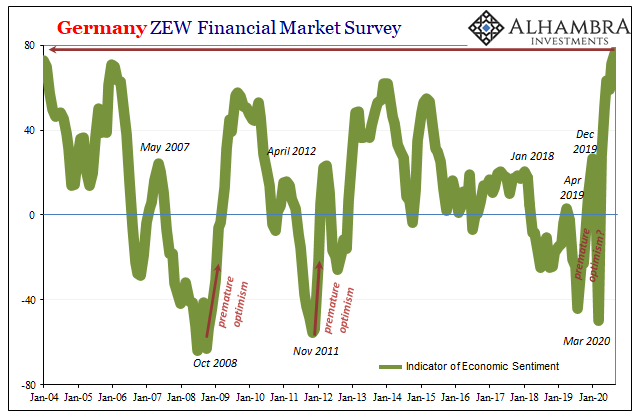

On the one side – the so-called hawks. Not just Germans, this group says the economy is (as always) doing really well. What recession, they questioned in 2019. Huge economic hole in 2020? Europe’s roaring back, baby! It’s always party time at hawk HQ, everyone drunk, they claim, on too much punch.

The other side, obviously, the usual doves who look at inflation and the other economic statistics and can’t make sense of either the data or the hawks. Monetary policy is awesome and powerful, yet these are forced to remain dovish year after year after year.

The hawks, therefore, always confident about a future that never shows up while the doves wondering why it never does. The doves want to join the hawks but after having gotten a whiff of the punchbowl they can’t but wonder why it smells like a combination of kerosene and the contents of a discarded baby diaper. Ironically, this leads them to the position it should never be taken away. Ever.

The ECB’s Governing Council had met on September 10, and all seemed well publicly. Perplexed mainly by a stronger euro, the ECB’s policymaking body had released their harmonious statement (and Lagarde managed not to screw it up) anyway.

Then Philip Lane.

The very next day, September 11, apparently unable to toe the ECB line Christine had negotiated, the ECB’s Chief Economist took to his blog to warn about the euro, yes, but basically everything else. A “stronger” currency exchange value Europe can’t afford, even if in historical context it really hasn’t been that big of a move.

Their carefully crafted more neutral statement thrown out the window with one swift stroke, igniting controversy all over again. Lane wrote:

Inflation remains far below the aim and there has been only partial progress in combating the negative impact [of the crisis]. Over the coming months, a richer information set will become available that will help to inform the calibration of monetary policy.

You see, as a central banker or a staff member you’re never supposed to admit this. The one big thing (the one wrong thing) all these central banks from the Fed to the ECB had taken as their preferred lesson from Japan’s failed QE experiments in the early part of this century was, in a word, confidence. Dammit, lie if you have to.

Never, ever admit it ain’t working.

Mr. KOHN. They were lurching from one policy to the next, each time saying that they didn’t think it would work. So I do believe it’s important that we decide before we get to the point where such policies need to be triggered…at least on a very rough sequence of what we will do and how we will talk to the public about it. We don’t need to be very specific; but before we begin to use nontraditional techniques, I think we need to talk about them publicly and create a sense of continuity and confidence in our policymaking, which I believe was absent in Japan.

Above was the consensus view FOMC members had expressed and agreed to where it came to these “nontraditional techniques” back in June 2003 after having studiously reviewed what everyone (in private) agreed at the time had been the Bank of Japan’s big failure. Their QE didn’t work because, mainly, they needed to tell the public over and over it was working.

We’re all morons, you see, easily dazzled and manipulated by shiny objects.

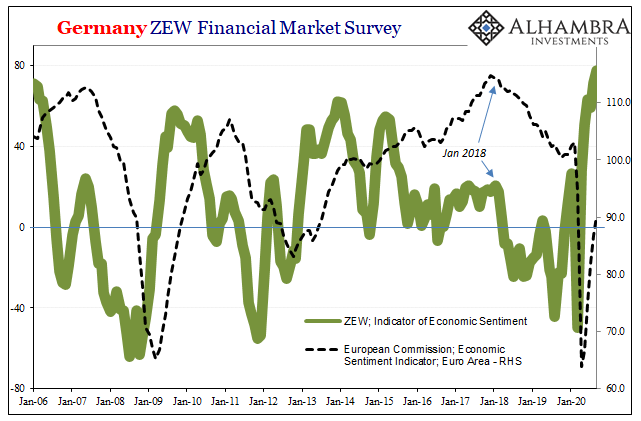

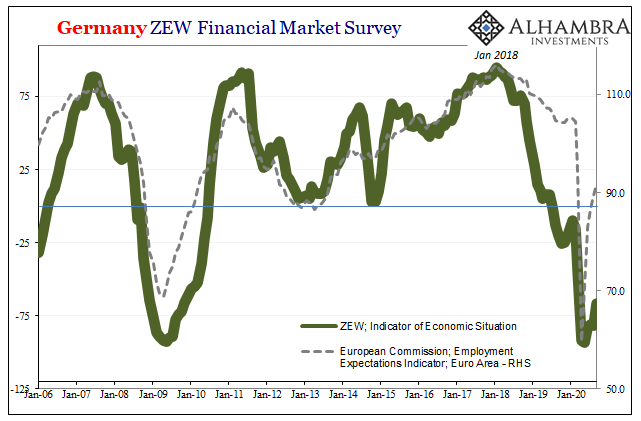

The problem for Philip Lane in 2020 is therefore obvious – he said the quiet part out loud. It isn’t working – to the extent even us morons can see it in everything except things like ZEW sentiment (where anything the ECB does tastes pure sugar). Like Mario Draghi’s policies and those of the Fed as well as Japan, they all keep hoping that time ends up the only missing ingredient.

Give these things enough time and they’ll work. Keep up the act until then. Two decades isn’t enough, apparently.

Lane was criticized by the hawks and doves alike, though maybe because so much time stuck in each respective corner has sapped what might be left of everyone’s sanity. Was everyone really mad at Philip Lane?

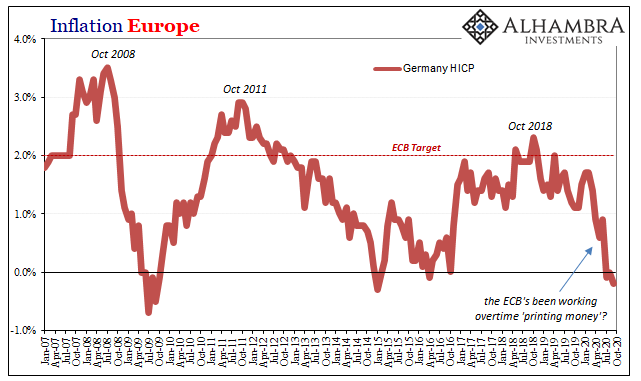

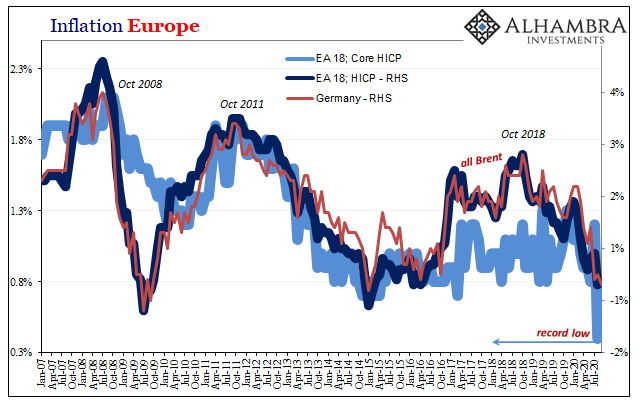

More bad news today. Germany reported its flash inflation estimate for the month of September 2020. Six months of massive monetary and fiscal “stimulus”, and in general German consumer prices continue to fall. Yep. Fall, as in go lower, discounting, minus sign (-0.2% y/y to be specific). The opposite of both hawks and doves’ expectations.

This follows August when the core European inflation rate had registered its lowest (by far) on record.

Policymakers – like the media which parrots their every word – have been quick to cite the VAT tax cut as the primary reason, but anyone who’s been paying attention the last two decades know European officials are, once again, mimicking their Japanese counterparts. Excuses like policies, it doesn’t matter the location since excuses after failing with their policies is always the one constant.

And what happens in Germany is what largely happens to the rest of Europe, meaning yet another month squandered waiting. For the record, much if not most of Europe has been in recession continuously since at least the third quarter of 2019, stuck with a persistent downturn that began two and three-quarters years ago. They just need more time!

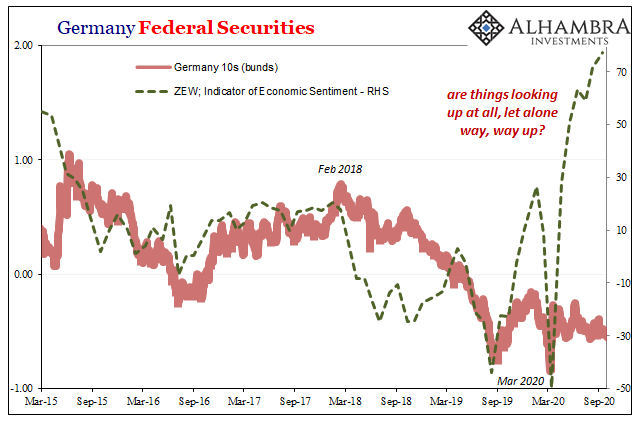

Why aren’t bond yields anywhere flying upward at all the money printing and fiscal insanity? This is a rhetorical question, by the way.

Not one of these central bankers is a serious person. None of them.

Stay In Touch