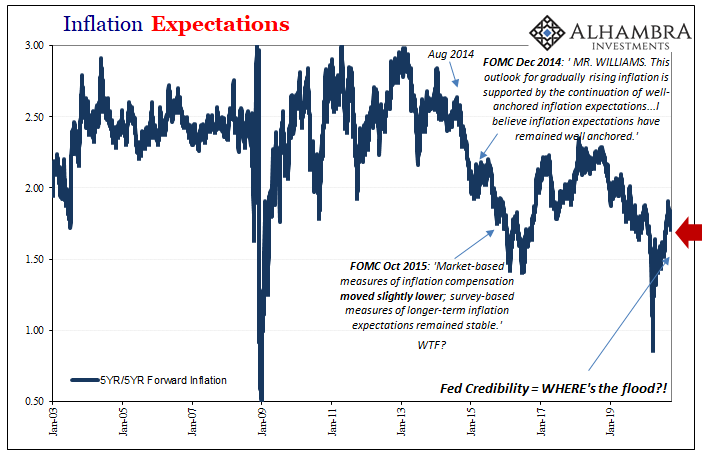

I missed it: did anyone ask Chairman Jay Powell how in the world he’s going to be able to create this “hot” inflation he already needs to balance out a decade without it (meaning: recovery and growth) in order to satisfy this newfangled average inflation target? And though he makes it sound like it’s a new thing, especially adding the word “flexible” before the term, it’s actually not new at all. But it sounds better if you think that it is.

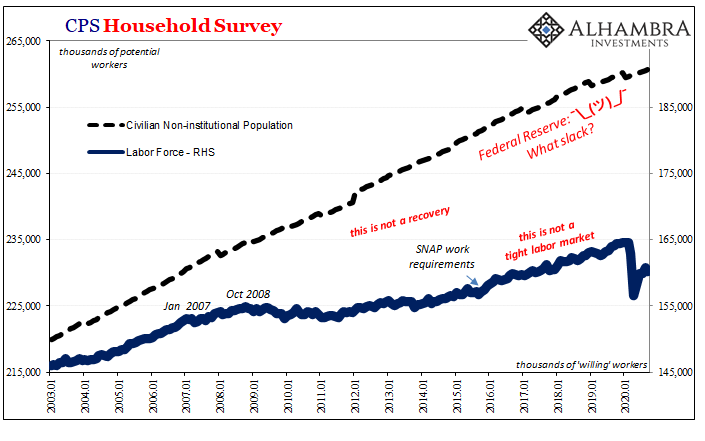

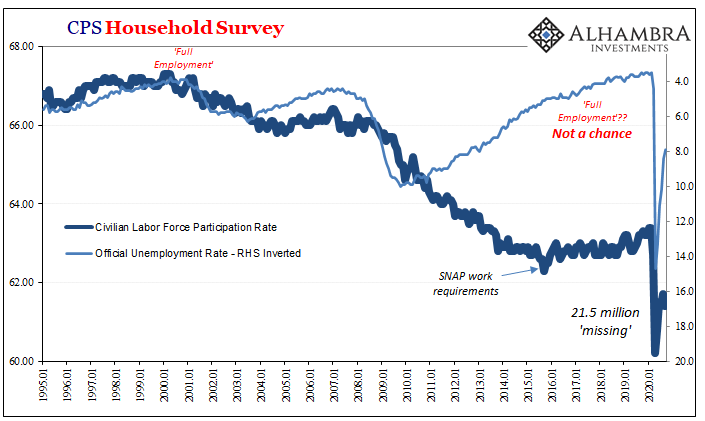

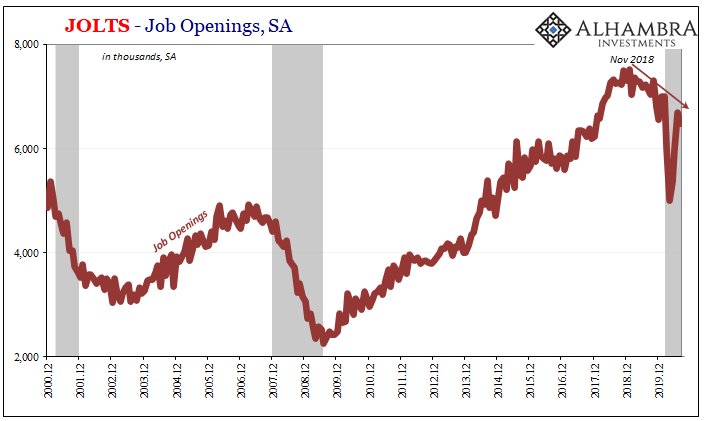

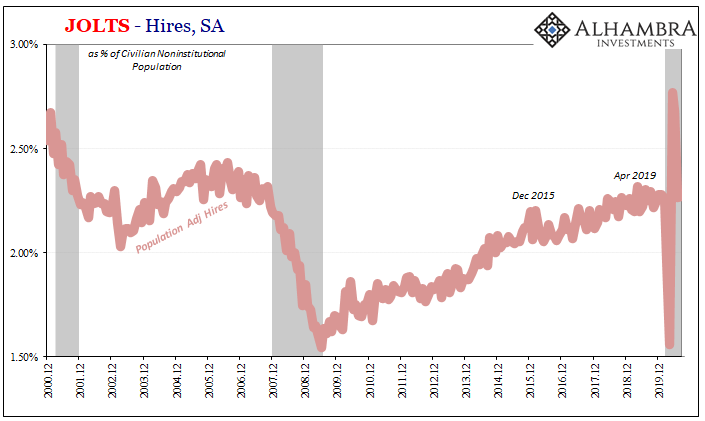

To have any chance the Fed will first have to close the output gap. Yep, slack. That’s what’s been missing since 2008, in that we haven’t actually missed slack – it’s been persistent slack all along. Economists and the Fed (same thing) have tried to come up with all kinds of ways to explain away the participation problem in the labor market.

Those were just overly academic means of avoiding what’s really quite obvious. What was it that happened around, say, October 2008?

In public as well as in private discussions, it never dawned on these people to connect the dots: how the constant need to attend to the global monetary system might have been the very reason for the lack of recovery energy.

Deprive any animal of oxygen and watch how it doesn’t move very fast.

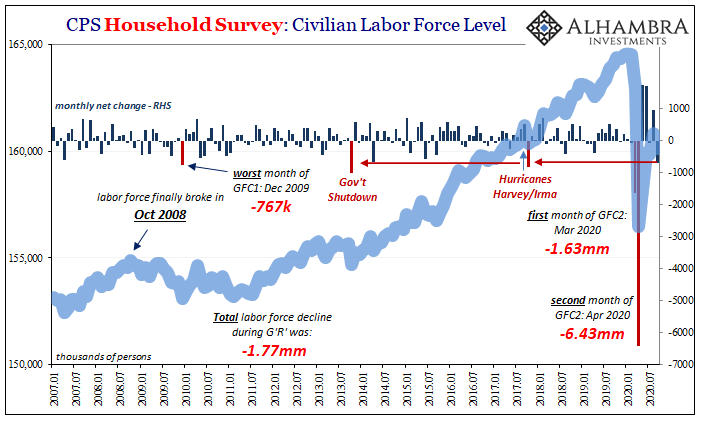

For the first time in modern economic history, the labor force actually shrunk during recession. The economy wasn’t just suffering an enormous, temporary setback, what’s called the Great “Recession.” For all its monetary evils up and down the line it was being broken – just like that same monetary system breaking everything down.

As Janet Yellen tried to say a few years ago, GFC1 should have been a once-in-a-lifetime proposition. But it wasn’t; March 2020 showed up and showed yet again how the people like her holding these positions of influence and authority refuse to learn even the most basic and obvious lessons.

The same consequences are now again staring right back at us right now from within the labor market.

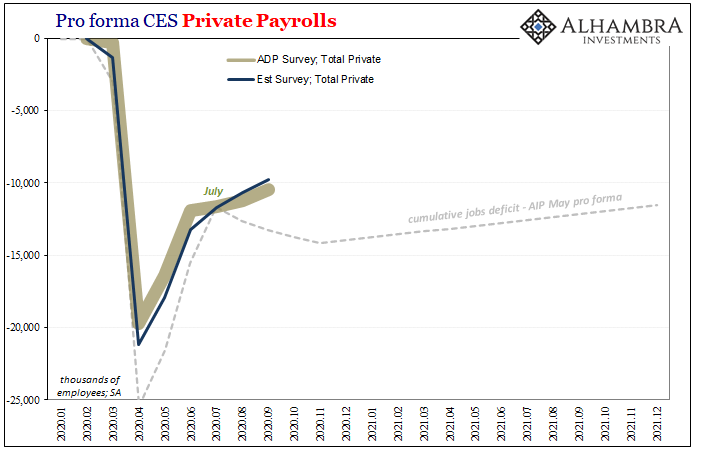

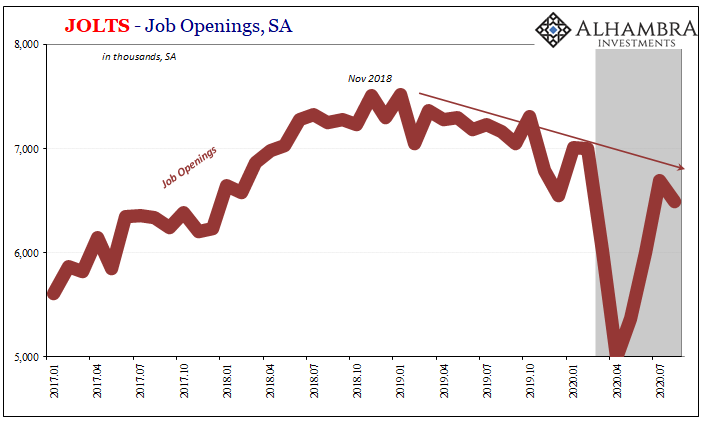

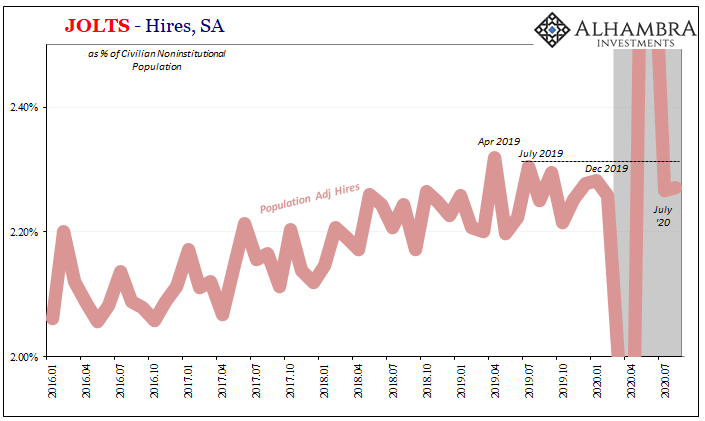

Not just payroll data, either. The JOLTS data also keeps backing up this idea of a slowdown forming in the trajectory of both the CES and CPS series. More and more it looks like the economy is running out of momentum well short of the finish line. Again.

As I’ve said, survivor’s euphoria – but then what? Once the sugar rush of making it past March and April with the cash flowing from the federal government (instead of work, earnings, and wealth), once this artificiality subsides, then we might begin to better able picture the economic damage suffered from this unnecessary disaster.

And if there is economic damage, well, we’ve been there before.

We just can’t have ten million Americans or more out of work for a prolonged period. How do I know this? Because we never even got that many during the absolute worst of GFC1 and it became, as I wrote above, a total breakdown. Before COVID, there was still 2008’s leftover slack to deal with (see: below).

What CPS, CES, and now JOLTS are suggesting is that the labor market is slowing down – maybe way down – far, far short of even minimal recovery.

So, I ask again, where is Jay’s overheated inflation supposed to come from? No wonder he’s up in Congress begging for assistance. Some people love that this might mean more “stimulus” without ever considering just how dangerous this situation must be that the Fed Chairman is so (openly) desperate for it.

I call it QE2 syndrome; misunderstanding the significance, many cheered in 2010 when QE was repeated when they should’ve been horrified realizing how the first one obviously hadn’t worked. If you need more, the problems are only just beginning.

Stay In Touch