Back in late July, the government of Ecuador opened negotiations with a particular set of what it called institutional bondholders. Like so many other nations, every other nation, Ecuador needs dollars and borrows them from global markets. Eurodollars, as in directly bank loans, those have been harder to come by post-2013.

Eurobonds, however, they’ve been somewhat of a different story especially during 2016-17’s globally synchronized growth nonsense and the tainted repo backing behind it.

Having leaned heavily on the Eurobond market, Ecuador in 2020 has fallen on hard times forcing it to seek concessions. That’s what the July talks were about; threading a very fine needle between threatening bondholders with outright losses in order to bring them to the table while at the same time not going overboard with the threats which might then threaten Ecuador’s ability to operate in those same bond markets in the future.

What they came up with was a complex debt swap – including, like dealing with some street-level loan shark, tacking on any missed interest payments to the $17.4 billion in principle the tiny nation already owed. In dollars it doesn’t have and has no real way of getting them with the global economy in the shape it is truly in.

The newly-created Eurobond securities (though they aren’t technically those since these are non-market paper) allow Ecuador to skip principal repayments at least until January 31, 2026; and that’s just the first ~third of the whole amount. Another third gets deferred until January 2031 before the final third which won’t start any repayments until January 2036.

The final agreement was signed at the end of August, supported by a reported 98.5% participation in the swap. Ecuador’s finance minister was thoroughly pleased, telling reporters how it, “allows us to maintain access to international finance and focus on reactivating the economy, generating employment and social protection.”

About that “maintain access” bit. Mere weeks later, in late September:

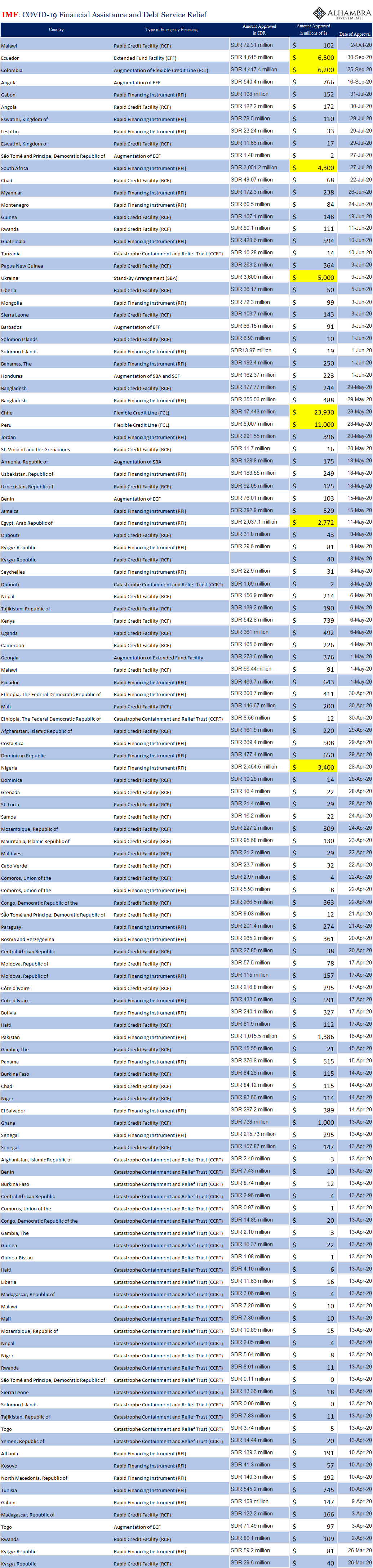

The Executive Board of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved today a 27-month extended arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) for Ecuador, with access equivalent to SDR 4.615 billion (661 percent of quota, equivalent of US$6.5 billion). The Board’s approval allows for an immediate disbursement equivalent to US$2 billion, available to the budget.

Nearly seven hundred percent of the country’s IMF quota is, to put it mildly, an extreme amount. On August 31, Ecuador had successfully restructured its Eurobond debt and then by the end of September, one of the busiest months on the calendar for all Eurobond issuance, its finance officials are at the IMF pulling in one of the largest post-March dollar bailouts.

So, did the swap really allow the country to “maintain access to international finance?” Maybe not. But why not?

They weren’t alone. Just five days prior, on September 25, Colombia had negotiated access to the IMF’s Flexible Credit Line (FCL). Not only big dollars, this was a big deal because it was the first time anyone anywhere had ever used this program even though the FCL had been set up during the first Global Financial Crisis – thereafter having sat dormant until September of 2020 six months into the world’s latest “recovery.”

Both Ecuador’s and Colombia’s rescues were greater than $6 billion each.

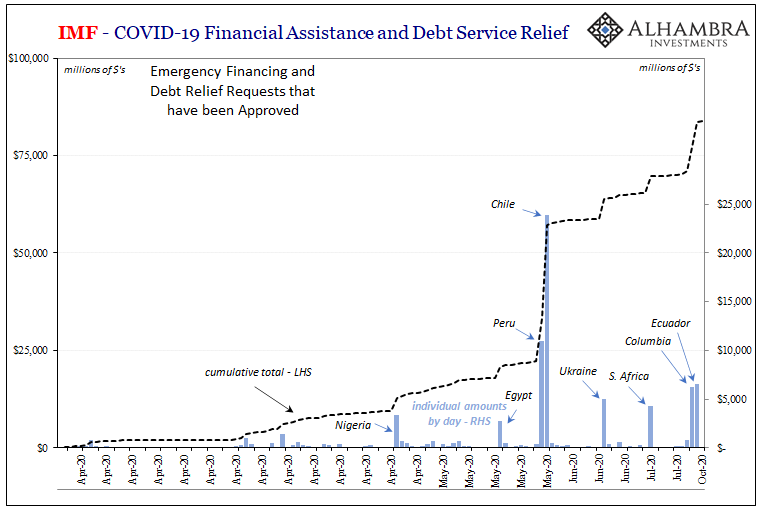

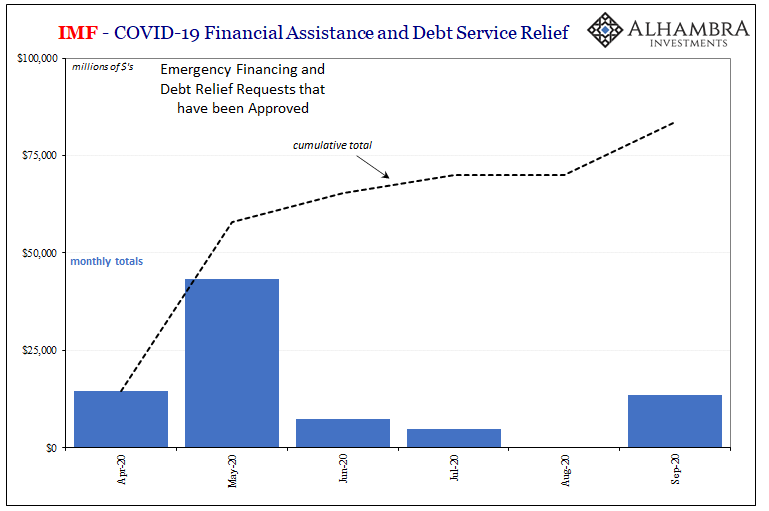

The IMF, like the global marketplace, seemed to be having a good run throughout the summer. Gigantic positives in nearly every global economic account almost regardless of which country it might have been associated with. Q3 2020 was, from the narrowest standpoint, a rip-roaring success which was also reflected in the lack of business at the IMF.

Global dollar bailouts had tailed off in July, and then in August there hadn’t been any at all. Something happened in September, late September specifically, which seems to have triggered renewed urgency in some of these weaker eurodollar (and Eurobond) situations.

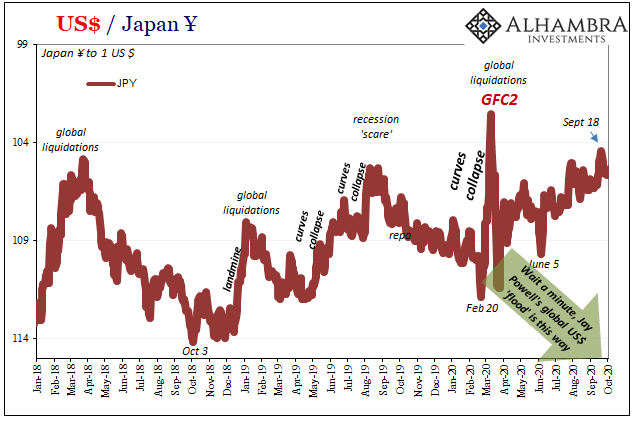

Again, September is a hugely important month on the issuance calendar. Might it have had something to do with the dollar’s sudden bid? Why was the dollar suddenly bid? As we well know, an upside dollar is little more than the downside funding/money supply issues behind it.

Not long after Jay Powell’s ridiculously absurd average inflation targeting stunt at Jackson Hole at the end of August, first India’s rupee then China’s yuan followed by quite a few others (including, as noted, a noticeable bump in credit spreads).

Rather than dollar-crash as advertised all during this wonderfully gigantic summer, the season ended with major handouts at the IMF.

The Fund’s justification for its Colombian action, activating the FCL for the first time, is actually a warning about what’s really going on here, a stark reminder that Q3 2020 wasn’t – by itself – significant to the overall economic story.

At the time of the [liquidity line for Colombia] renewal, the extent of the pandemic fallout was unknown, and the economic contraction turned to be deeper and more protracted than expected in May…External risks are higher, given the substantial uncertainty about the pandemic’s future course. At the time of renewal, we projected GDP to shrink by 2.5 percent; now, our growth forecast is -8.2 percent.

Abundance of caution, the organization claims. The real situation in Colombia, as the rest of the world, isn’t yet known. The world suffered a huge setback, and then it rebounded. That’s really all we know thus far.

Rebound isn’t necessarily recovery, a more than likely possibility that our collective experience since 2008 has universally demonstrated. And in places like Colombia, where the government has acted in the textbook manner, the textbook approach hasn’t been anything like a guarantee of stability let alone staying long-term damage-free. You do have to love how they try to spin it:

Combined with Colombia’s comfortable level of international reserves, it provides the added insurance against heightened external risks.

September’s dollar bid, meaning heightened dollar shortage, was just a little blip; a minor reminder that not everything is proceeding swimmingly in a “V.” It wasn’t hardly anything disruptive and yet, Ecuador and Colombia ended up at the IMF anyway for big bucks.

Because they are confident in the way things are progressing, knowing they’ve got a “comfortable level of international reserves” in hand? Absolutely not. It’s a wonderful phrase for a dispassionate press release intended to be read by a hardly interested public who still might give these people any benefit of the doubt.

In truth, in the eurodollar and Eurobond markets, the words that were actually acted out last month weren’t those, instead the relevant phrase was this one: “heightened external risks.” Dollars, in other words. In September, after an entirely uneventful summer of gigantic positives.

Q3 2020 wasn’t the fairy tale upside bookend to Q2’s monster decline. It was hugely positive, sure. Q4, however, begins the real deal, and, truthfully, most of the second and third order stuff we won’t really know about until next year starts.

If only Ecuador like Colombia could count on Jay Powell’s inflation nonsense for once, some truly inflationary currency spiking commodity prices to provide them and so many other places around the world with dollar (crash) relief. But, like Eurobond investors in 2017, betting on central bankers has been proven time and again fool’s gold.

Stay In Touch