Why do we care so much about inflation targeting in any form? Ask that question of a central banker and they will merely state the answer is self-evident before calling the police to have you arrested and thrown in jail for daring to query. Inflation targeting is central to this version of the central bank, so much so it has tossed the very idea of “full employment” into the garbage just so it can continue on with the program.

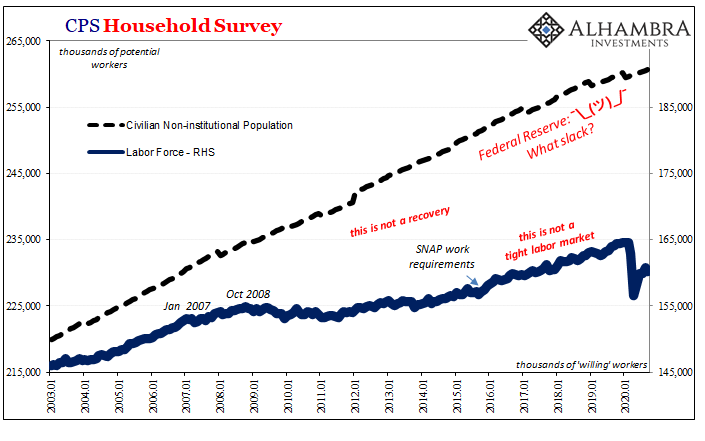

For everyone else, the issue is more practical. Think about Jay Powell’s task as he sees it: the economy is a huge mess and in order to get out of it the Federal Reserve can only offer a highly glossed, refined vision of a very hopeful and fruitful future. Fret not about today, dear laborer (and tens of millions of former laborers), there’s so much better to come – you just can’t see it now.

Take Jay’s word for it. Not only better to come, he’s saying he’s going to allow it to be downright overheated on the other side of things.

The original “V” used to be about how easy it was to turn everything back on. This new “V” is about how useful “stimulus” will be now that the first narrative has fallen apart. So great, overheated!

Essentially, you and I are being asked (demanded?) that we forget about today and put all our faith, eggs, and cash flow in Jay’s inflation targeting future basket. Averaged out, he’ll only do you right.

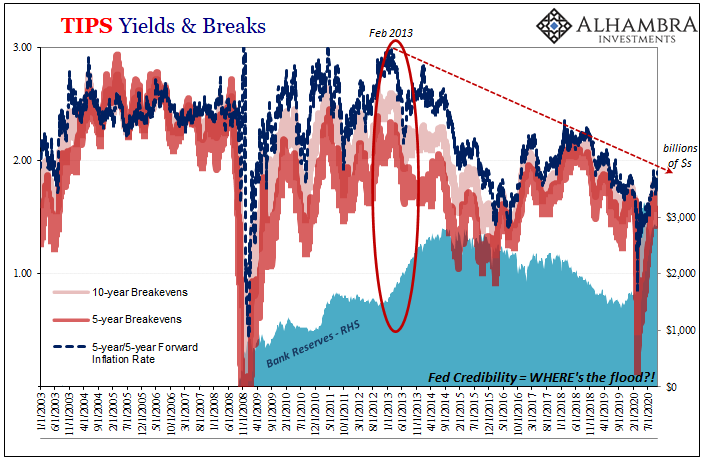

The combination of this higher implied level of forward inflation plus the massive QE undertaken to clear the path to this future is something we’ve seen before. As always, it’s already been done and if it’s QE-related it’s already been done (to death) in Japan. We keep repeating Japanese experience with these very same methods if only following up from seven years behind them.

So, in order to properly inform our views of inflation targeting plus massive QE we need only turn the calendar back just a little more than seven years to the first months of 2013. Did that already yesterday in examining the practical applications of the US repo market and eurodollar context as they related to future inflation (meaning meaningful economic growth) prospects. Here today we’ll go over to Japan to explore the theoretical background and years more of additional practice.

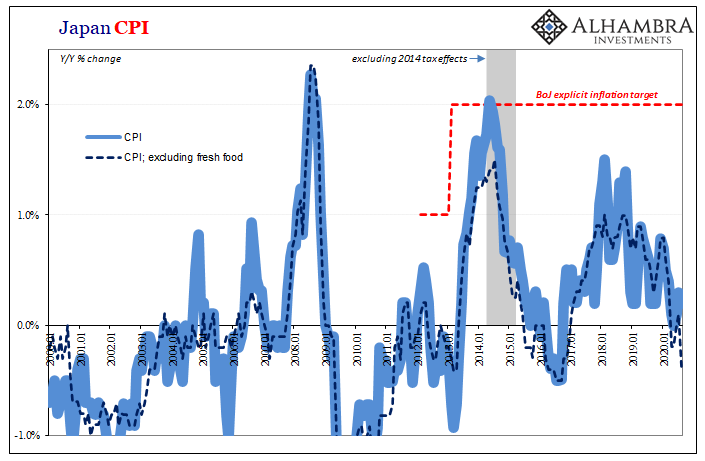

It begins with the introduction of an explicit inflation target. Like the Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan waited until early 2012 to establish one. In February of that year, BoJ announced that it in order to make its intentions even more plain (what Bernanke had earlier called a “modest bit of additional transparency”) as if its desire for more inflation wasn’t already, the prior generalized statement of considering inflation between 0 to 2% as ideal got whittled down into a more specific goal.

Japanese central bankers still wanted to use the range of 0 to 2%, which had only implied a 1% midpoint goal, so now in February 2012 they declared that 1% level to be the explicit target. Why? Because officials in having trouble 2009-11 thought they might want to reinforce this message to the public, that the BoJ would continue to do whatever needed to make sure inflation reached 1%.

Not for a single month, either, or a few at a time here or there. No, an inflation target means general consumer prices advance by around that much month after month consistently. Some months it might be a little more, some a little less. Over the long run, however, the target’s the level inflation should dependably revolve around with only minor variations (massive variations, like a decade of undershooting, well, that’s average inflation targeting).

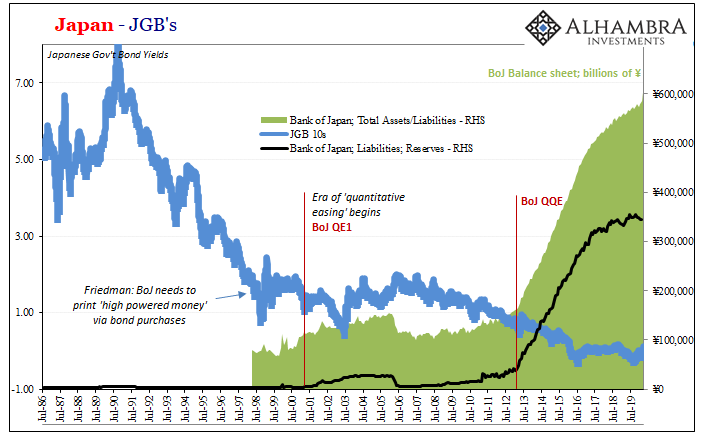

The introduction of Abenomics later in 2012 upped the ante. Before it assigned the central bank an even greater role in Japan’s promised recovery, the Bank first took the step of raising the inflation target to 2% from 1%. In January 2013, Haruhiko Kuroda announced the raised target as well as the first outlines for what would become QQE – the radical increase in recklessness being urged by all the conventional Economists.

Their guiding principle was still the same one espoused by Paul Krugman in the nineties: credibly promise to be irresponsible. On the one hand, QQE sure seemed like reckless, irresponsible money printing to any layperson (as intended). On the other, an inflation target moved up to 2% which meant to reflect both the central bank’s tolerance for the consequences of that irresponsibility as well as its commitment to “overheating.”

And it never happened.

Instead, QQE remains ongoing now well into its eighth year while the Bank of Japan reached its 2% target just one time, one single month (not counting the effects of 2014’s VAT tax hike) out of the ninety-one since the target was raised – eighty-nine of those accompanied by QQE. In fact, BoJ wouldn’t have even been able to hit the prior 1% target the vast majority of the time since QQE.

In January of this year, the Federal Reserve – maybe looking ahead? – discussed some of these Japan, err, lessons.

First, the Japanese experience shows that an announcement of a higher inflation target does not guarantee that inflation will increase to the new target level, even if the announcement is accompanied by a historically unprecedented degree of monetary accommodation. One could argue that the BOJ could have provided more accommodative monetary policy by even more aggressive asset purchase programs, interest rates at more negative levels, and better communication strategies. However, although such additional actions might have helped raise inflation to the new target level, it is highly uncertain whether these additional actions would have led to substantially higher inflation in Japan. In particular, there is a high degree of uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of asset purchase programs, especially when the size of the central bank’s balance sheet is already large, as well as regarding the effectiveness of negative interest rate policy…

Thus, in thinking about whether to raise the inflation target to a certain level, central banks need to take into account whether they are able to raise inflation to the new target level. If a new inflation target is too ambitious, and the central bank fails to attain it, the central bank may lose its credibility, which may render less effective any other policies it pursues. [emphasis added]

Hear that, Jay? From your own central bank’s research. Bloomberg? CNBC? Anyone out there in the financial media? Bond Kings? Bueller?

A key reason why is simply because central banks have been designed since the Great Inflation to be inflation fighters. Inflation targeting was meant for an era when the risks were always tilted upward (though because of eurodollar money growth central banks know little to nothing about instead of the random good luck they described).

Always looking backward, policy orientation is never prepared for the opposite possibility. The real history of the modern central bank is far, far more comedy of error than mythically precise technocracy.

As I stated on one of our recent Making Sense podcast, for decades after 1929 the Federal Reserve like all central banks was focused entirely on preventing deflation – because that was the big issue it had been rightly chastised (and reformed) for failing to prevent – costing the country, and the world, several decades.

And while engrossed in deflation-fighting, the Fed (and other central banks) following the Great Depression allowed instead inflation to get loose on the economy while they were looking entirely the other way.

After seventeen years (1965-82) of it being wrecked by the polar opposite monetary condition central bankers never saw coming, central banking was again turned upside down to forget entirely about monetary shortages in order to refocus all its efforts based on what was already in the past; fighting today’s battle with tools (poorly) designed for the last one.

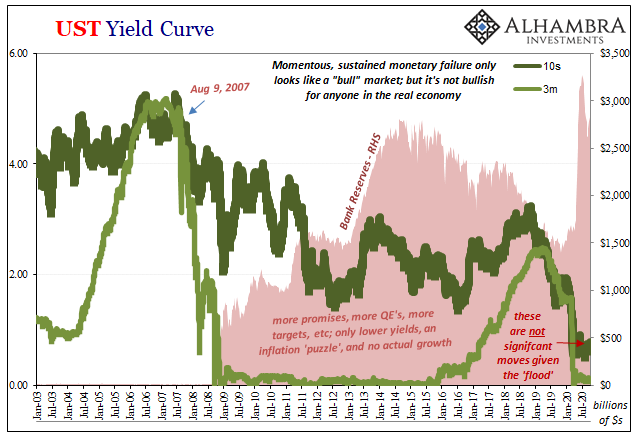

What happened starting in August 2007 was therefore predictable; looking out for only inflation, officials totally missed the deflation creeping up while they were again caught looking the wrong way.

So, what specifically went wrong in Japan with 2% plus QQE? You would never know it from mainstream media coverage, but there is a mountain of even mainstream academic scholarship, pardon me, crapping all over QE’s, QQE’s, inflation targeting, etc. The most charitable of these, like the one above, say the benefits of these programs are “highly uncertain.” A more realistic qualification would be “failed in every way.”

Yet, in the current financial media you are led to believe these things always work, work well, maybe even too well.

Here’s one written by and for the Bank of Japan in July 2017 which attempted to explain why after three years of QQE plus 2%, the “irresponsible money printing” hadn’t achieved much (or anything).

Specifically, we provide empirical evidence for what factors caused the actual CPI inflation rate to fall short of the BOJ’s original forecast made in April 2013, by using historical decomposition technique of simple VAR analysis. The empirical results show that among the deviation of the CPI inflation rate for fiscal 2015 from the original forecast of minus 1.9 percentage points – the difference between the forecast of 1.9 percent and the actual result of 0.0 percent – about 50 percent (minus 1.0 percentage points) can be attributed to the unexpected decline in oil prices. A little more than 10 percent (minus 0.3 percentage points) can be explained by the unexpected slump in output gap and a little more than 30 percent (minus 0.7 percentage points) by inflation-specific negative shocks. [emphasis added]

Yeah, to start with, a full 100% miss. Supposed to have been one point nine and inflation in 2015 had turned out instead all of zero.

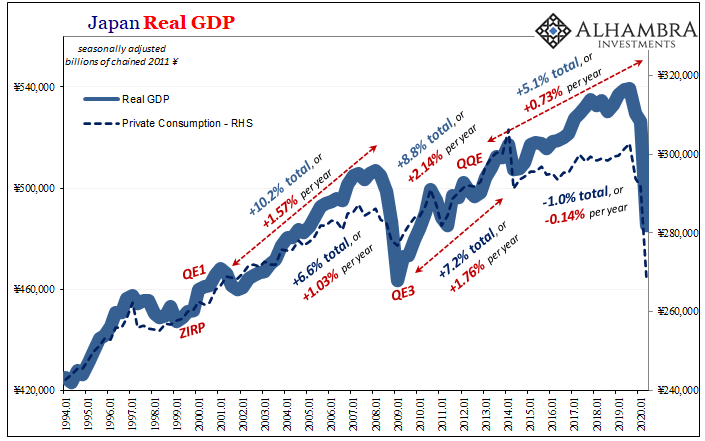

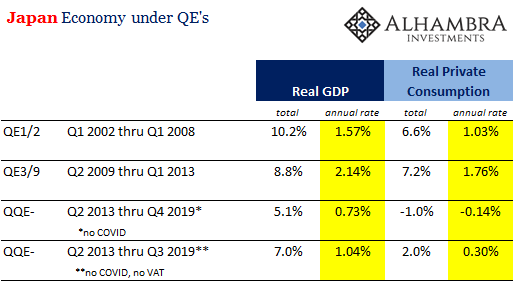

Again, it’s not really about just inflation. Even taking out each of the recessionary declines, QE’s – particularly QQE – come up short in every possible respect:

To put this into context, real GDP in Japan during Q3 2019 – despite all the QE’s and inflation targets – was just 6.4% more than it had been in Q1 2008 at the prior peak. Six point four total, not per year.

Seasoned eurodollar observers will notice how in the second half of the quote above all of the reasons given for this shortfall sound exactly like what a eurodollar squeeze produces: declines in oil, unexpected of course; economic growth, or output gap, coming up short, unexpectedly; and the ubiquitous negative shocks always associated with global downturns produced by any Euro$ #n.

Central bankers can see, but don’t yet know, we live in the eurodollar’s world.

In short, there is absolutely nothing legitimate upon which to base the Fed’s late 2020 more optimistic inflationary forecasts. Nothing. It’s all smoke and mirrors, a tired puppet show increasingly lacking the slightest originality. The entire monetary toolkit consists of uncritical stories written up in Bloomberg and for CNBC. That’s all it ever was.

The “yeah, but we won’t screw up like the Japanese did” excuse doesn’t even fly anymore – since everything has turned out the same way anyway.

These are not central bankers, but they do play them on TV.

As I keep writing, these are not serious people – but these are serious times to have such unserious officials officially clueless about the most serious issues. It might as well still be February 2013.

We absolutely need a real recovery here after a decade already of not getting one, and in order to get one now these are the only people available to us. This is what the new “V” narrative is predicated on. How is this supposed to be a happy thing?

You absolutely need to know this. Bond yields, like inflation and inflation expectations, are incredibly easy to understand.

Stay In Touch