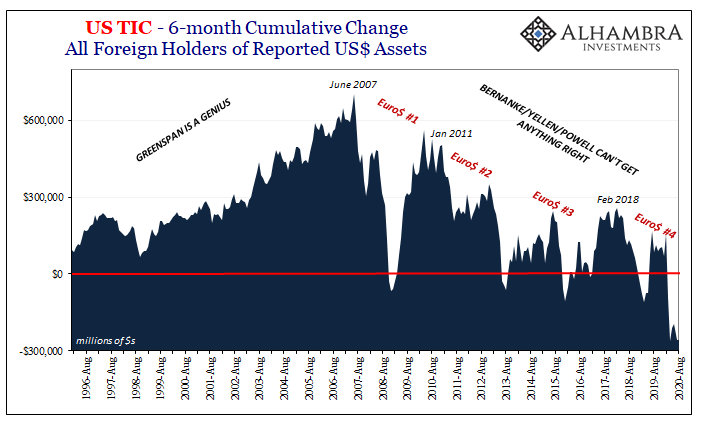

It does seem, at first, a huge contradiction. On the one hand, what we know so far of China’s 14th 5-year plan apparently will lean heavily on new technologies not-yet invented to rescue the country’s economy from the pit of de-globalization the eurodollar system had thrown it into years ago. If the global economy isn’t going to recover, and there’s absolutely no sign that it will, then the one seemingly logical (though far-fetched) way forward would be if the Chinese economy converted itself into an enormous self-sustaining island.

Geopolitical pressures related to COVID and what that did so far as getting global companies to rethink their supply chain weaknesses was simply the last straw (on both sides, apparently).

But to create a such an independent economy from scratch, the Communist Chinese will have to do what no true communist would ever think of trying. Thus, it would stand to reason that China’s high-flying tech sector, while behind the West in most ways, would be the necessary ingredient behind thinking up all these “unheard of” technologies so that this transformation has even the smallest chance of working out (not incidentally, thus why this next 5-year plan is really a 15-year pro forma for the first time).

Yet, Emperor Xi has unleashed his army of bureaucrats onto the tech sector anyway. This is how, short of actual guns, purges are conducted in the modern Socialist manner. You get accused of first being a corrupting influence before then eventually charges of “corruption” finish you off. Only now has this metaphorical authoritarian fist been extended in this conspicuous direction:

While Xi’s government has been steadily tightening its grip on the world’s second-largest economy, it has until recently taken a relatively hands off approach toward businesses that dominate China’s burgeoning internet, e-commerce and digital finance industries. Authorities are concerned the companies have become too powerful, according to Ma Chen, a Beijing-based partner at Han Kun Law Offices.

We can’t ever know for certain, but we might begin to suspect the Chinese tech sector (especially so-called fintec) may not be so enthusiastic about “unheard of” technologies and the new China being planned for in its 14th. Rather, existing successful companies (and their easy targets of billionaires in leadership roles) might be understandably reluctant to just climb aboard Xi’s preferred way forward, preferring instead to thrive alone as they can, as they have, in the broken, de-globalizing economy even if that can’t ever recover.

That’s the thing about the Communists and their “solidarity.” Collectivism requires that everyone share equally of what mostly works out to pain. When the eurodollar system was working and China was riding high on it, that rising monetary tide lifted everyone allowing for authorities to tolerate the widening inequality bottom to top. There’s not any room for such disparity anymore.

It’s Xi’s way or the highway (a very wide road leading straight to “corruption” trials), because even in the Communists’ China it remains today the eurodollar’s world.

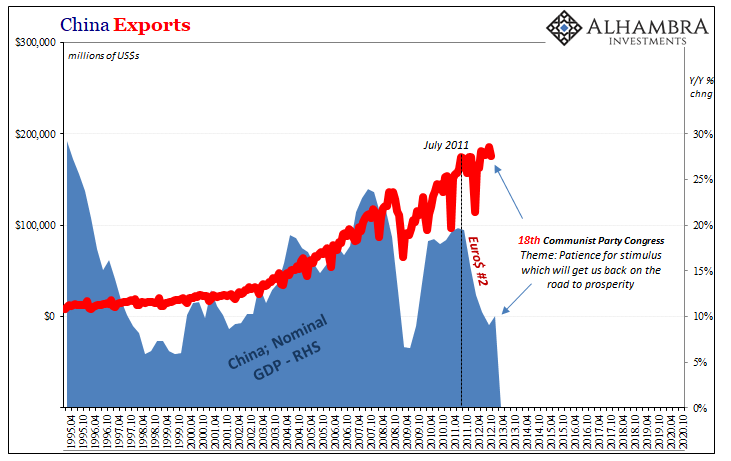

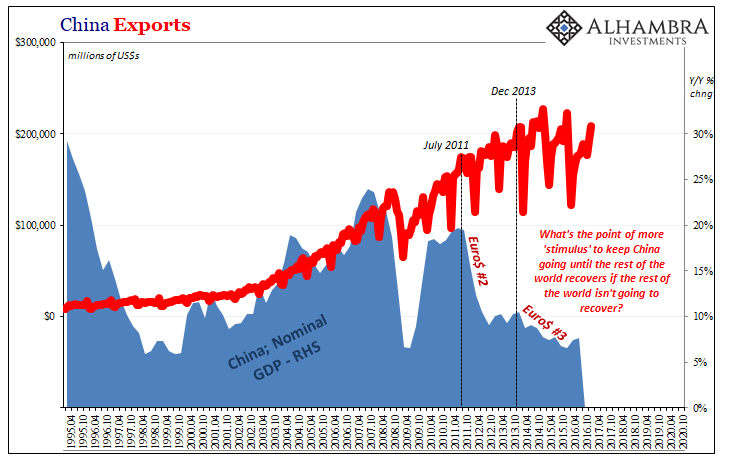

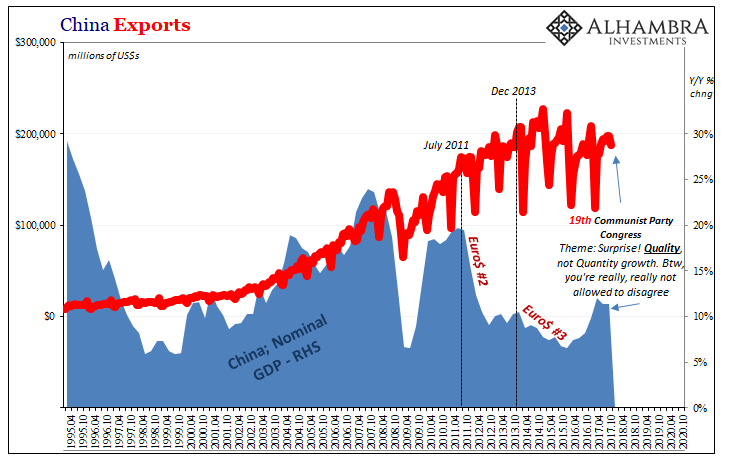

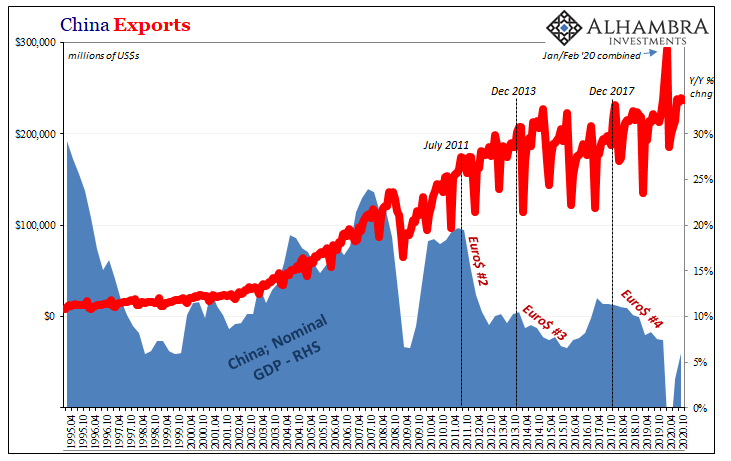

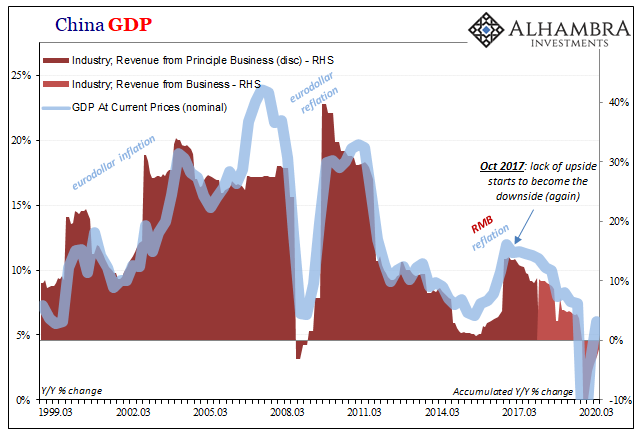

Late in 2020, while a mystery to most in the West who continue to think of China’s economy as a source for global strength – the same mistake they made in 2017 – Xi’s actions – like his in 2017 – suggest the opposite for which there is growing evidence he, not they, has got it right about where China stands and what that really means globally.

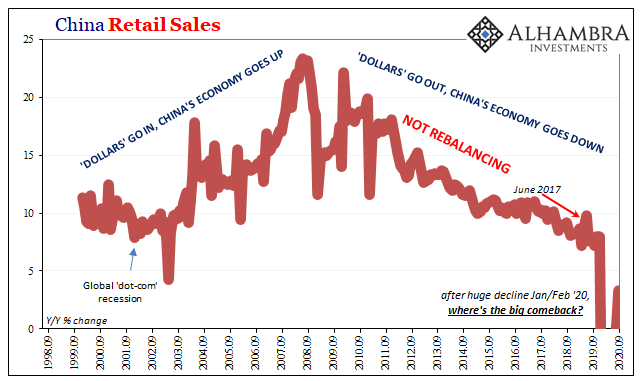

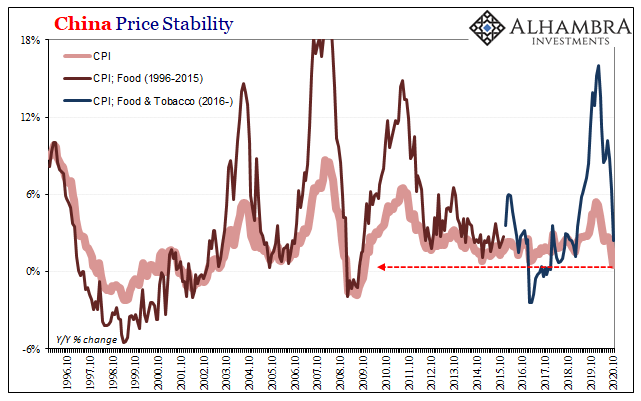

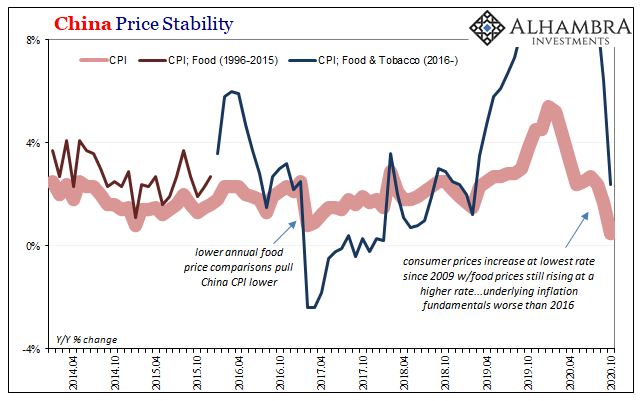

Not just the lack of sufficient rebound of already-insufficient global trade, internally there’s all sorts of continuing negative indications about demand at home. Consumer prices, China’s CPI, increased by only 0.5% year-over-year in October 2020. That was the lowest rate in eleven years, since October 2009.

As the Chinese pork problem comes under control, and food prices stop skyrocketing like they had last year, what that has revealed since the contraction hit in 2020 is just how sluggish the rebound from it has been. Like Europe, not just external demand problems, here in consumer prices is more evidence internal demand isn’t coming back far or fast enough, either (see: retail sales).

Since the 14th 5-year plan is also the first to codify “dual circulation”, which (like “rebalancing” had already tried to without achieving much of it) prioritizes this internal growth over the previous economic paradigm which depended upon mostly external means for progress, it’s not off to a good start (thus, the latest escalating crackdowns?)

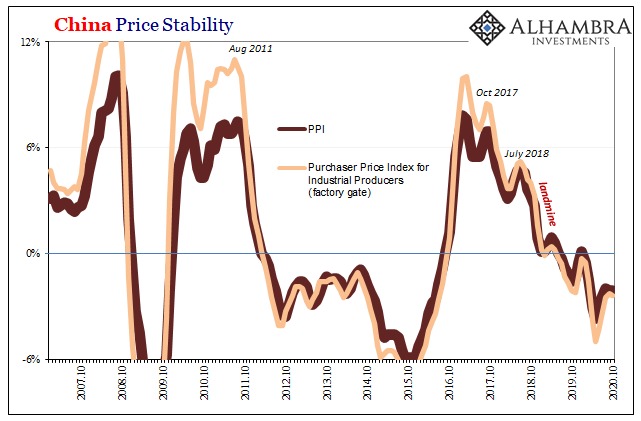

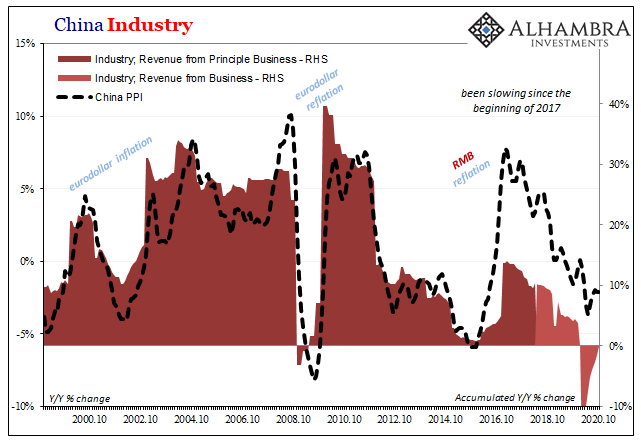

On the external side, again prices, there are rampant indications of continuing overcapacities. Having shown up last year under Euro$ #4’s globally synchronized downturn, producer prices have kept falling throughout 2020’s initial contraction right through also the rebound from it.

Producer and factory gate prices establish that even at lower levels of output (or growth in output) it’s still too much despite what should have been, if this global recession was entirely virus-related and non-economic in nature, a thorough and unambiguous upside showing up certainly before October 2020.

And while compelling in their own right, China’s PPI changes, along with those in factory gate prices, are unusually strong indications for how the Chinese economy overall will fare (below). While their next 5-year plan aims to rely more heavily on the internal piece of its “dual circulation” model, the system remains more so attached to external demand right now (again, “rebalancing” since 2012 didn’t achieve the separation).

Production is still China’s main engine, and producer prices keep saying it’s not coming back near fast enough; serious price discounting the result. Thus, both sides of “dual circulation” at the moment are projecting only the same sluggishness (in reality, as opposed to Western mainstream characterizations and colored interpretations) already presented across the broader, Big 3 economic accounts.

In other words, if it doesn’t seem like Xi is expecting big things from his economy this year and next, maybe even up to 2025, that’s why more and more we should expect it will become “his” economy. Despise the man and his system, but you absolutely have to pay attention to what he’s (still) doing – not what everyone else is saying about the situation.

Not just to put together a coherent and honest sense of what’s happening in China, but also what that means about what must really be happening in the rest of the global system. Doing so in 2017 would have had you prepared for what actually happened in 2018 and 2019 (not inflationary recovery and acceleration, in other words), and there’s little to suggest anything has changed since.

In fact, that’s the whole thing.

Stay In Touch