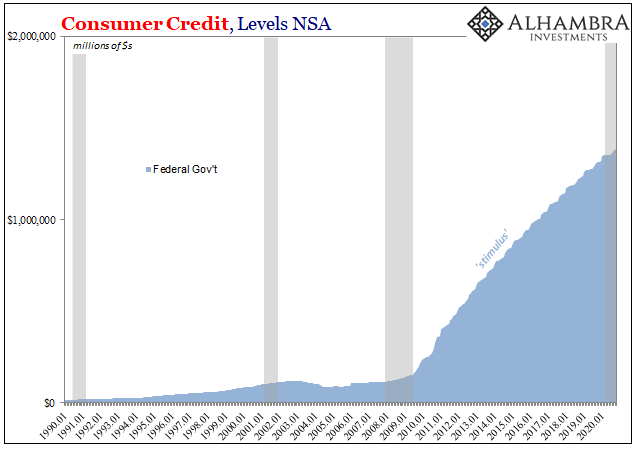

If anything is going to be charged off, it might be student loans. All the rage nowadays, the government, approximately half of it, is busily working out how it “should” be done and by just how much. A matter of economic stimulus, loan cancellation proponents are correct that students have burdened themselves with unprofitable college “education” investments. Without any jobs, let alone enough good jobs, an entire generation of Americans has been hamstrung, absolutely holding back legitimate economic growth.

In this area, at least, too much debt has been a very clear sign of unproductive finance. Not banking, however; government.

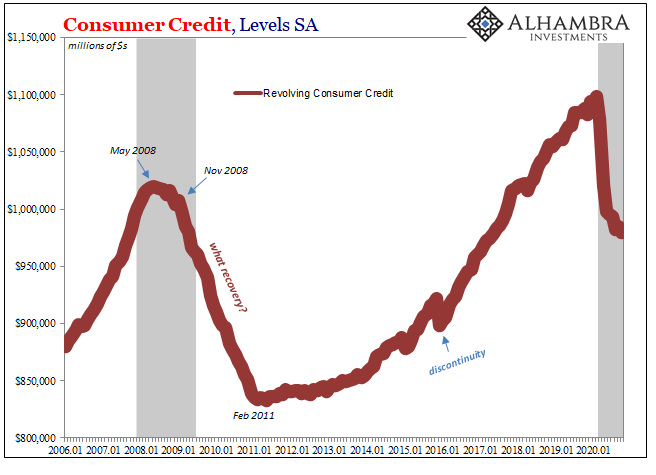

On the opposite end of consumer credit from student loans, suddenly there’s now too little credit being extended – for the same reasons. A mixture of supply side contraction, banks and other financial firms becoming reluctant to make loans, while demand for credit has waned for these troubling economic perceptions.

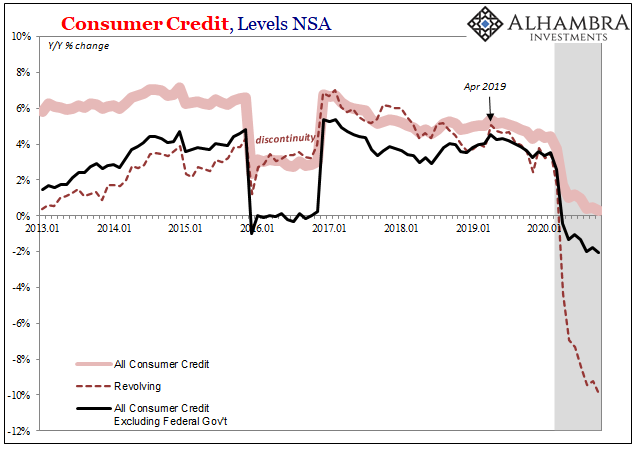

Aggregate declines in outstanding credit card balances are pretty clear signs that consumers in the upper ends of the income spectrum are uncertain – at best – about their own near and intermediate-term prospects. Credit cards at times like these get paid down rather than charged-off, widespread repayment of non-discretionary revolving loans a defensive measure, a sign of prudence and risk-aversion.

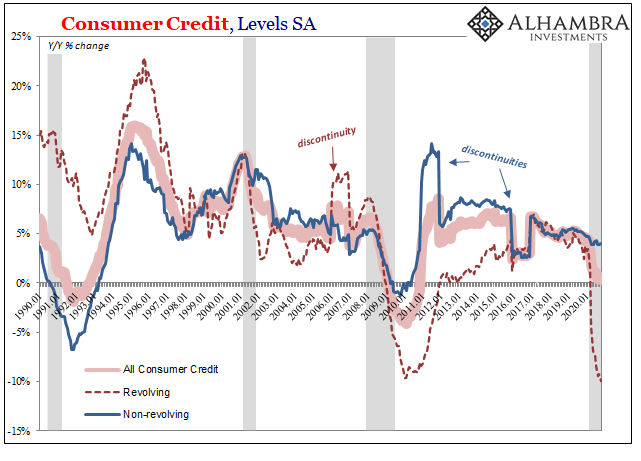

According to the most recent data compiled by the Federal Reserve, the latter, revolving, keeps declining while, forever upward, student loans are newly minted by the federal government at a near-constant rate no matter what (thus, this loan “crisis”). Total revolving credit declined by more than $5 billion during October 2020 from September, a rather steep monthly contribution to the seasonally-adjusted estimates already illustrating seven months of the same to this point.

As we’ve noted several times before, this despite the Federal Reserve’s best efforts to turn these rather dour perceptions around. Monetary policy, especially as it might influence the sentiments of fund managers, seeks to reassure consumers (and businesses) by supposedly raising inflation expectations and reinforcing them with concurrent increases in share prices bid higher by those fund managers comforted in Jay Powell’s mythical “put” (no matter how many times discredited).

Consumers are then meant to act on these signals. Declining balances in revolving credit show that monetary policy, while clearly having the intended effect on Wall Street, the message isn’t being fully received on Main Street. No exuberance, caution reigns here.

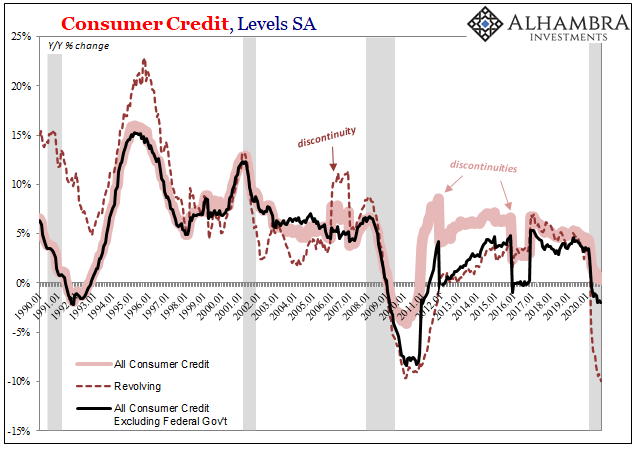

This is no new development, however; only the rate has changed recently. In truth, consumers have been careful about consumer credit since around May 2008. Though levels have risen in the post-crisis era in absolute terms, like everything else credit-wise around the world in the dollar shortage domain it still represents a categorical change in condition before and after GFC1.

Once you account for the non-economic artificiality of the federal government.

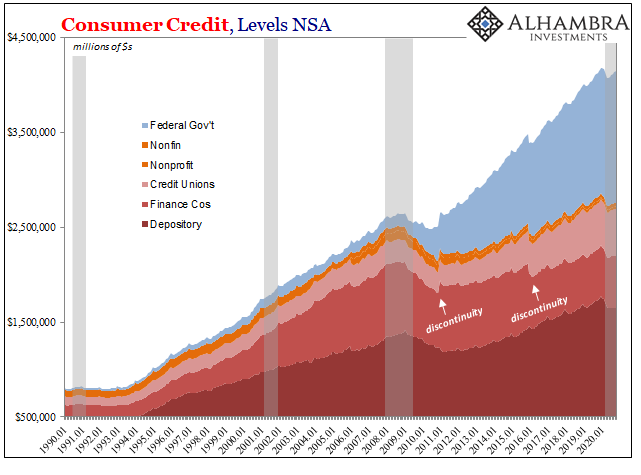

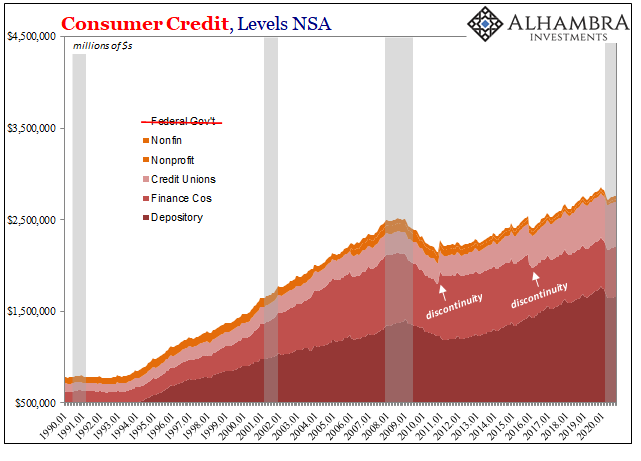

Overall, consumer credit had expanded by about 60% from the 2008 peak until February 2020. The vast majority of that increase, as you can see above, was in the form of student loans handed out regardless of any economic factors by the bureaucrats still dealing in leftover “stimulus” from the 2008-09 takeover of this part of the debt market.

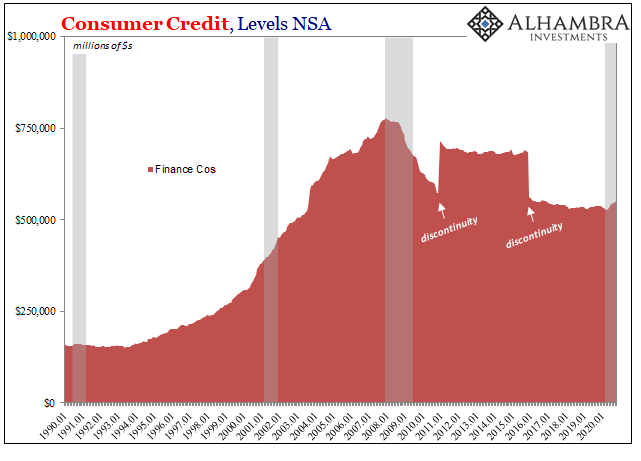

Excluding exploding college loans, total consumer credit gained just 13% total in the same time frame. After 2008, American borrowers as well as American (and foreign) financial firms have viewed the risks of borrowing/lending very differently than they had before. On the supply side, liquidity risk, especially at the wholesale level (where funding companies find the cash for their packaged loan activities), has reduced lending capacities substantially.

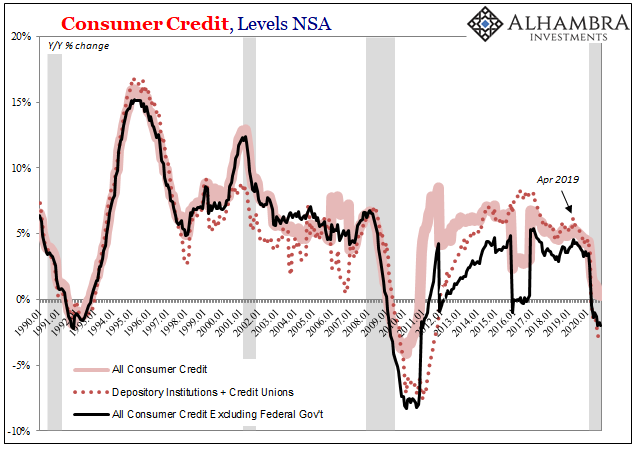

And all that was before we got to 2019. Early on in 2019 (2018 landmine), consumer credit growth outside the federal government had already begun to wane. Even depository institutions, including credit unions, were rethinking their risk strategies; and depositories are always the last to figure these things out.

Even with the federal government’s influence, non-revolving consumer credit growth has slowed since the beginning of last year – because the economy notwithstanding Uncle Sam’s redistribution schemes was suffering a downturn despite the Federal Reserve’s prior efforts aimed at Main Street sentiment with rate cuts and such.

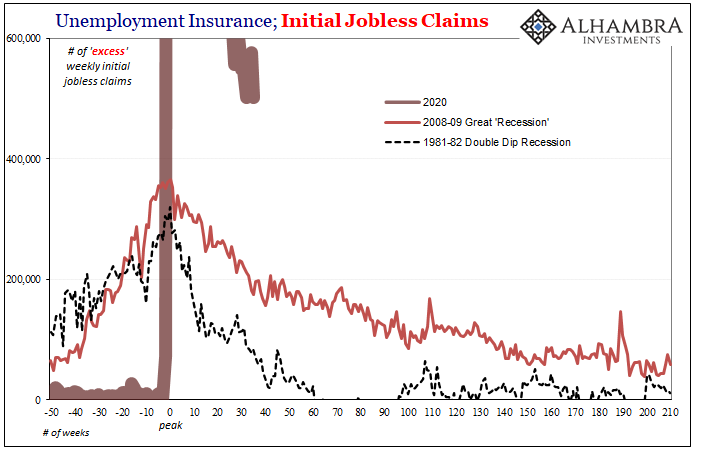

The COVID shock merely amplified the already negative pressures to the point that consumer credit growth outside student debt is declining in all categories to a degree not seen since the depths of the last financial crisis. Total consumer loans excluding those made by the federal government were 2% less in October 2020 than they had been in October 2019. That’s the same rate of decline as March 2009.

Consumer credit held by depositories and credit unions, including both revolving and non-revolving types, was down by more than 3% year-over-year. These kinds of financial firms weren’t cutting this class of loans at that rate until October 2009 – four months after the Great “Recession” was declared (by the NBER) at an end. Unlike then, banks and credit unions seem to have figured out what workers (as consumers) knew back then and know right now.

There absolutely has been too much student debt because the government pays no attention to any factors other than demand. On the flipside, there’s been “too little” of these other kinds of credit which before 2008, at least, had been economically useful in the sense of economic demand (whether it was sustainable is another question). True before 2020, there’s now substantially less consumer credit all the way through October.

And the slump shows no signs of ending.

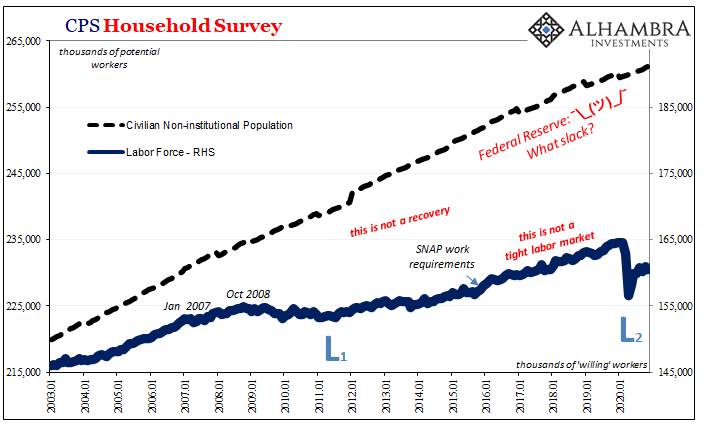

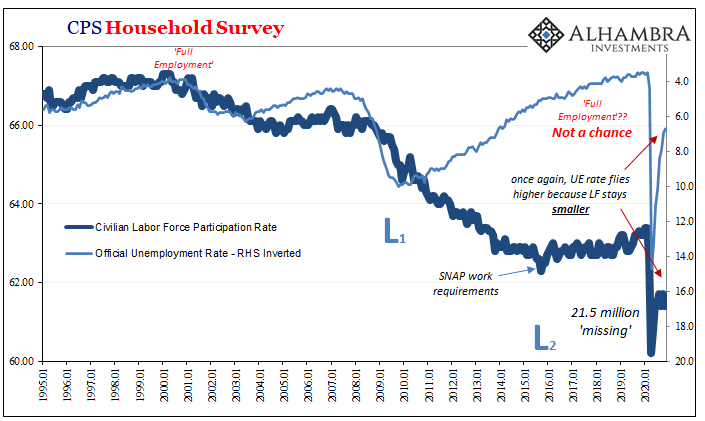

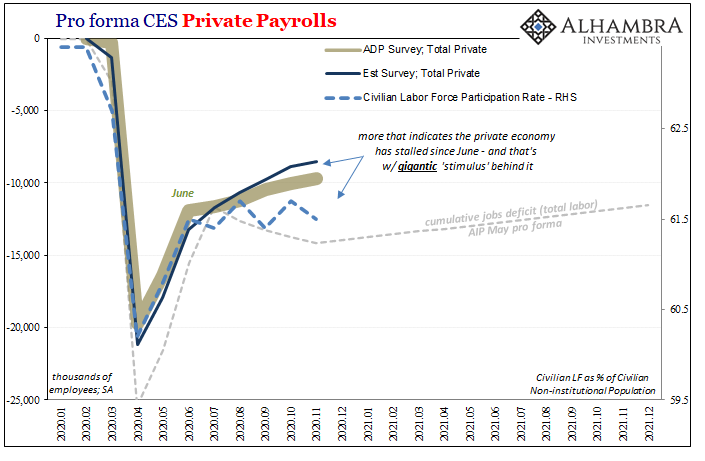

While politicians try to rebalance the equation on the education side of consumer lending, promising to forgive as much as they might be able to get away with, does vaccine-aphoria upend the reticence of economic borrowers and get them borrowing (therefore spending) freely again? Perhaps, but it doesn’t really seem all that likely especially since risk aversion (on both sides of consumer credit, supply and demand) is predicated almost entirely on the labor market as it actually is – not as a few people hope it could be maybe by the end of next year if everything goes just perfectly.

In the end, these polar opposites in consumer credit are saying something important about the state of the economy. The same thing. Jobs.

Stay In Touch