They were never very specific to begin with, even in Ben Bernanke’s infamous November 2010 Post op-ed covering the start of QE2. Officials like to keep it purposefully vague as a kind of dry powder, a margin for error. If bureaucrats become too specific, the public would reasonably hold them to their own standard being laid out. The point behind Alan Greenspan’s infamous fedspeak was, most of all, wiggle room.

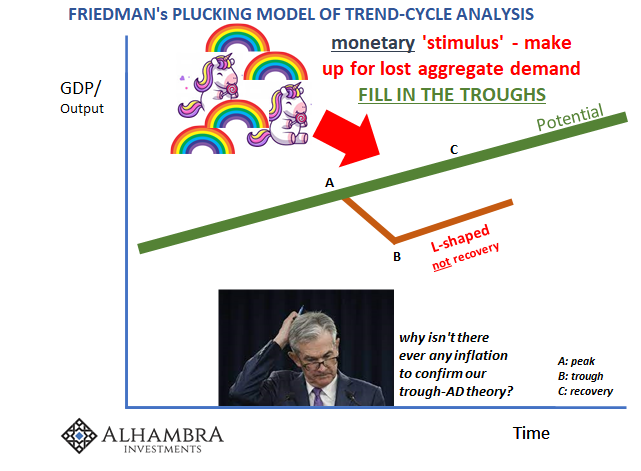

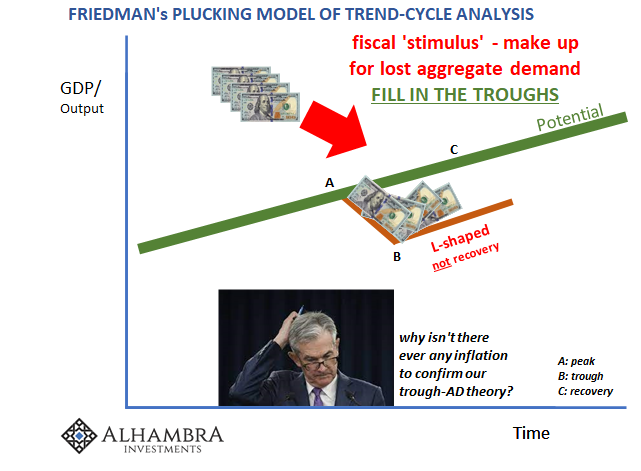

QE is going to help boost the economy. How, you naturally ask? Don’t say. Keep it ambiguous. At most point to the “financial system” and claim “accommodation” will make things “loose” and “easier.” None of those terms, you’ll notice, really answer your question.

How, exactly, do these things work?

More than a decade of this in the Western world, there’s only more of it on the horizon. In Britain, Silvana Tenreyro, an outside member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, endorsed negative interest rates (NIRP) just yesterday. Giving a speech at a seminar in Bristol, Tenreyo said studies show NIRP has “worked effectively” while “some of the evidence point[s] to more powerful effects.”

This view is supported, according to the BOE, by “strong evidence of transmission into looser bank lending conditions.”

What’s omitted from these situations is the only thing which matters. Monetary authorities worldwide should have made this incredibly simple: we do QE, full recovery follows. End of story. Happy ending, no less.

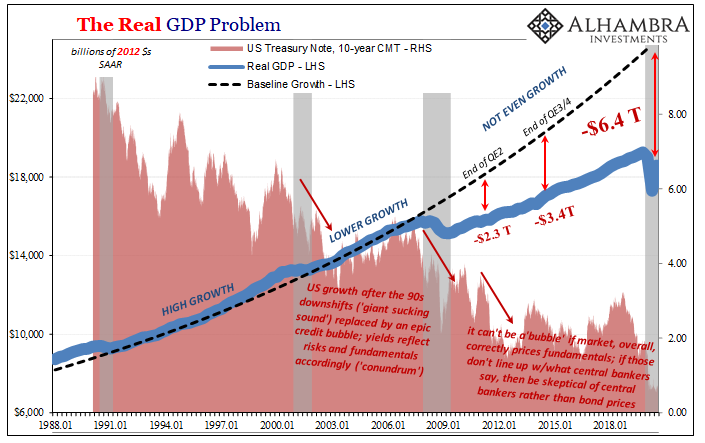

Instead, this is what central bankers time and again hint at and then watch helpless as the economy always falls short. In the meantime, interest rates – over time – only fall, too, because…

Why do they decline, exactly? If they do, why don’t they ever seem to come back up apart from small, temporary bursts?

According to the same nebulous doctrine utilized in the conventional narrative, interest rates follow along with whatever central bankers are doing; even if no one really knows what that is. Either way, low rates are “stimulus” in the Economics textbook, and no monetary authority will deny themselves the chance at such easy if incorrect correlation.

Since this intellectual vacuum has continued unchallenged for such a long time without needed correction (derived from an honest analysis of the evidence itself), it has led to a pretty widely held idea that bonds in particular have experienced an unnecessary and unhealthy “bull” market to the proportions of being in a bubble. A bond bubble.

From this perch, all the Bond Kings.

What is a bond bubble, anyway? Employing that specific term can only lead to a specific meaning. And that is any asset class or market which must be experiencing some kind of price imbalance beyond all reasonable thresholds. The stock market of the dot-com era provides a recent and near perfect example easily understood by everyone. Prices that outrun all fundamental prospects and reductions into rational valuations.

Given this, it may not be perfectly clear what that could mean insofar as bonds are concerned. Fundamentals and price imbalances, all most of the public really believes is that interest rates are low because central bankers and the media (same thing) have said they want rates that way. Officials seem to even want them to be negative, claiming it helpful (without being too precise about how).

The fundamentals for bonds – really meaning safe and highly liquid instruments, such as sovereign issues of the highest quality – are simply whatever factors which highlight these underlying characteristics. In terms of any potential bubble, whatever conditions when the safest and most liquid instruments could be priced at enormous premiums when there doesn’t seem to be any rational reason for them to have achieved such (extreme) over-valuation.

We know without a doubt from historical examples what those look like; when times are good, or inflationary, there’s no fundamental reason to overpay for safe and liquid. During heightened inflationary conditions, even less so. Fundamentally, over the intermediate and long run, the idea of a bond bubble is just that straightforward.

And let’s use one prime historical example: Japan.

This one is also incredibly easy to understand, requiring no fedspeak to color or off-color what is otherwise perfectly candid, rational analysis; and this is why you don’t hear much about what’s been going on in Japan for such a very long time.

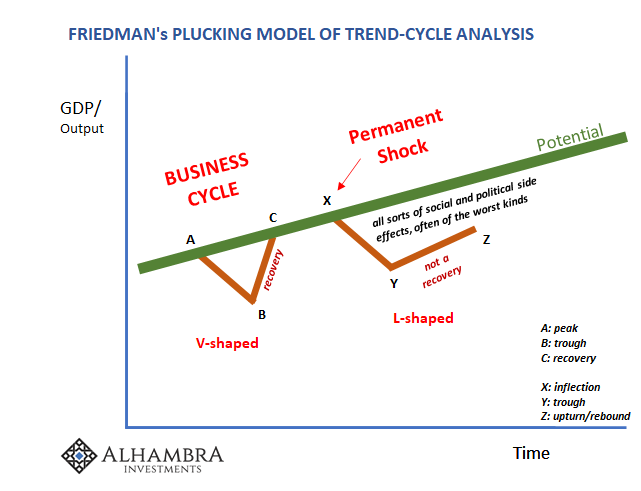

Time appears to play a huge role in this element of confusion. There is an idea that fundamental conditions like growth and inflation cannot remain undesirable for prolonged stretches (no unit roots or permanent shocks are allowed in econometrics; whether econometrics is an accurate depiction of reality is really the question); therefore, it is merely assumed, if bond yields remain low (meaning prices high) for a very long time it must be due to some artificial intervention or intrusion which has created a bubble that must necessarily end badly at some point.

Not just a BOND ROUT!!!! or even an actual bond rout, a true massacre.

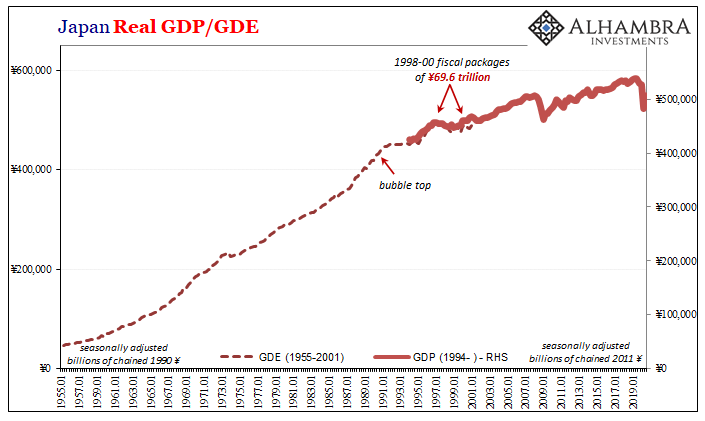

The Japanese example, on the other hand, neatly dispels this very notion. Start with Japan’s economic condition (note: Japanese economic statistics were reworked in 2000-01, meaning that older GDE figures aren’t directly comparable to the modern GDP estimates consistent with the way data is calculated around the rest of the world; for our purposes here, they are certainly within a reasonable range).

In the early 1990’s, the Japanese economy dramatically, obviously downshifted; you can plainly observe it (above and below). Before the epic bubble collapse which began in 1989, Japan Inc. had managed a miracle of massive growth from basically nothing (up to the seventies) and then sustained mature growth through the eighties.

More to the point, whatever growth had been “lost” in that final decade of the 20th century continued unfound in the 21st – right up to the current COVID-quarters.

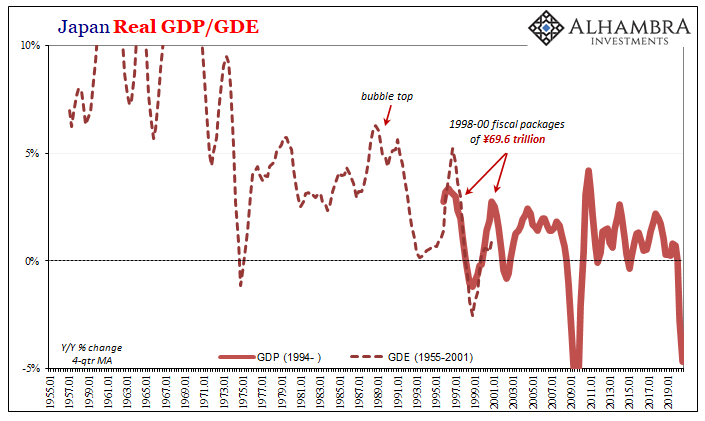

In terms of growth rates, there’s an absolutely enormous difference between an economy growing consistently between 3% and 5% per year, as in the late seventies and throughout the eighties, and one that gets stuck between 0% and 2 maybe 2.5% in its best quarters. Whatever you want to believe happened around 1990 that changed everything, the point is it changed everything for the Japanese economy in an inarguably permanent way.

From that time forward, growth hasn’t been much like growth at all – and it shows up like this across any number of related factors (social as well as financial or economic).

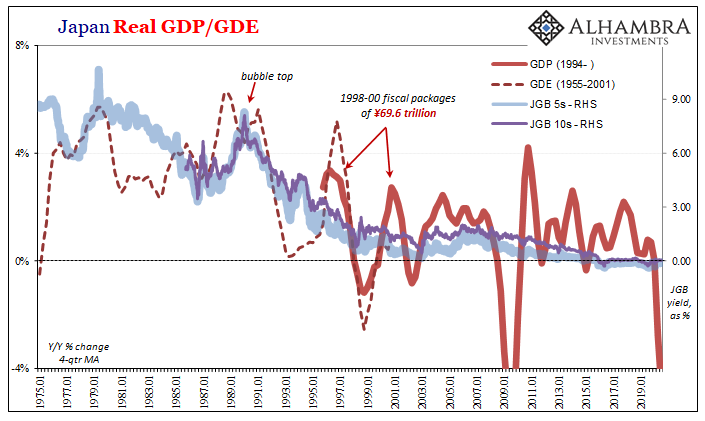

But as to the potential for any bond “bubble”, no, this is all just fundamental backing for a reasonable and rational basis behind persistently low interest rates. The fact that the Bank of Japan hasn’t been able to alter the underlying condition only establishes that the Bank of Japan cannot alter the underlying condition.

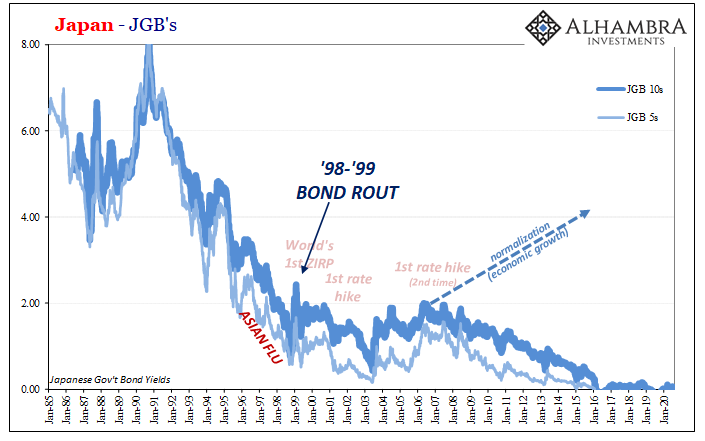

As real economic growth downshifted from the bubble peak throughout the lost decade of the nineties, interest rates quite reasonably declined – not because the BoJ wanted it that way (it didn’t, by the way, resisting first LIRP and then ZIRP), rather due to the fact the fundamental proposition of the Japanese system would only continue to favor risk aversion and therefore ongoing heightened demand for the safest, most liquid instruments.

Instruments the central government became only too happy to supply.

No fundamental imbalance, therefore no bond bubble. So far as time has been concerned, that’s only because – and this is the whole ball of wax right here – nothing fundamentally changed about Japan’s economy despite the passage of now three full decades. On the contrary, interest rates there seem to have properly priced the situation during all of it.

There never was a bond “bubble” in Japan. There still isn’t one right now.

It only seems unclear, perhaps preposterous when coming at it from the mainstream perspective which simply assumes central bankers know what they are doing. If they did, they wouldn’t need the constant stream of speechified ambiguities.

Monetary authorities (who don’t actually do money) are using, and even counting on, vagueness to sell you on a fiction, all the while believing that fiction will fix the situation already priced correctly by the safest and most liquid bonds yielding what little they do. In other words, low yields derived from a pitiful fundamental condition are the same thing as what drives central bankers to keep doing this over and over.

These two things naturally coincide; both are evidence of fundamentally failing.

This doesn’t mean rates won’t fluctuate and at times seemingly do so in seemingly large, concentrated moves (such as 1998-99 in JGBs), but they never represent, they certainly haven’t yet, this always-called-for end of the bond bull or the promised pin finally moved close at hand to begin popping the bond bubble. Time isn’t the factor you’re made to think it is. So long as the fundamental economic situation remains uncorrected, there can be no bubble. And it sure as hell isn’t all that bullish.

Japan, sadly, hasn’t been an outlier. Thus, neither has the “bond bubble” in JGB’s.

Stay In Touch