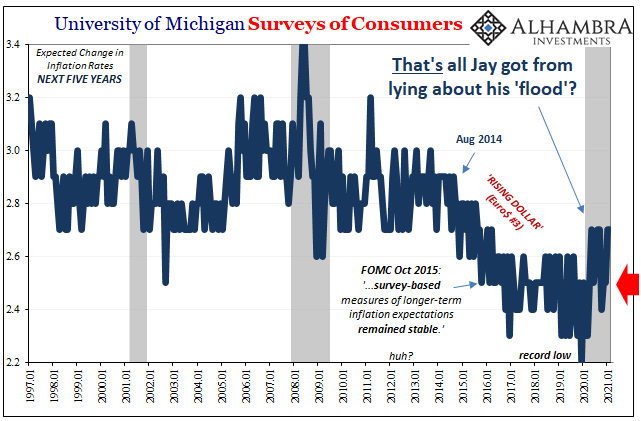

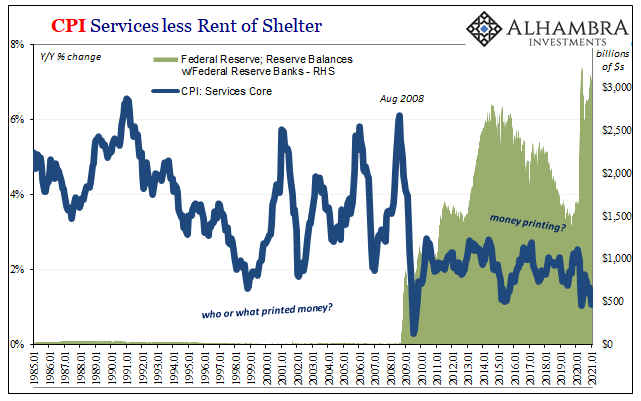

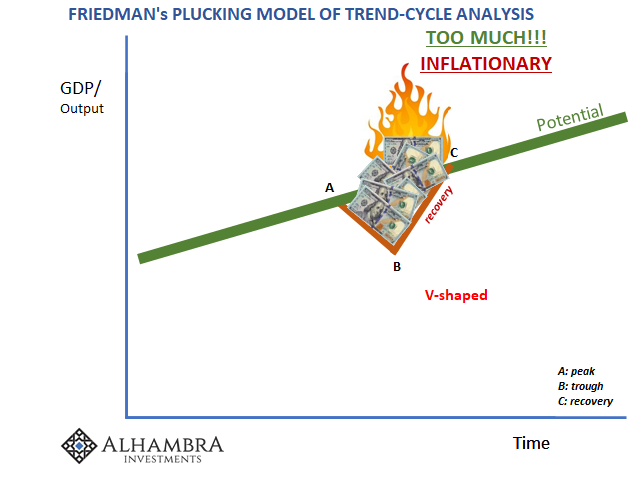

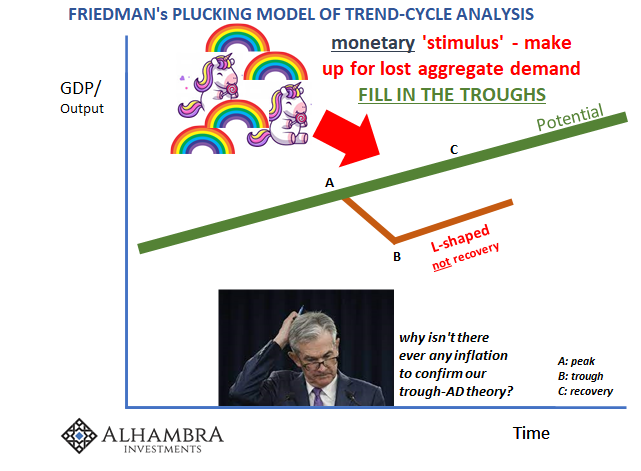

For Jay Powell’s inflation case, the University of Michigan provided it with some badly needed support. Telling the world he “flooded” it with “digital money printing” three-quarters of a year ago, actual inflation rates have instead fallen down to or near historic lows. No biggie, those in Powell’s corner say, just a matter of time before this changes (commodities!), possibly a lagged response to the overabundance of US currency.

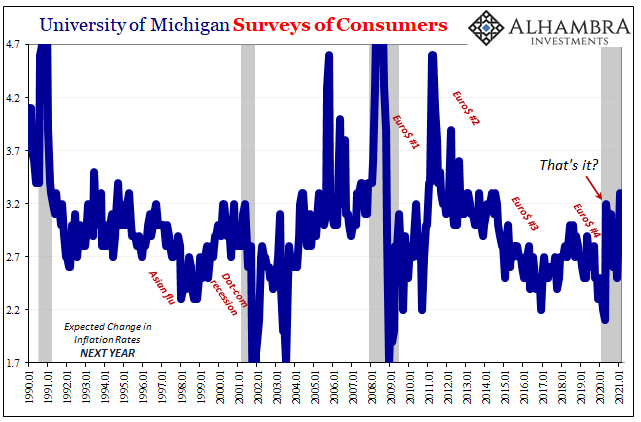

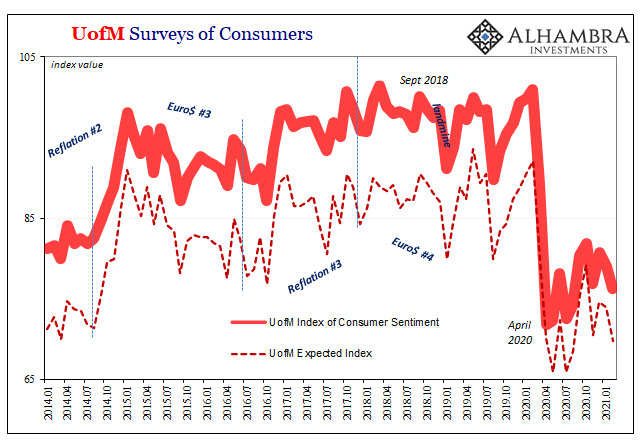

UofM reported today that the short run inflation expectations of consumers looking ahead one year from February 2021 perked up to 3.3%. That’s the highest in many years, nearly seven. You’d have to go all the way back in this particular data set to the average for the month of July 2014 to find an equivalent level.

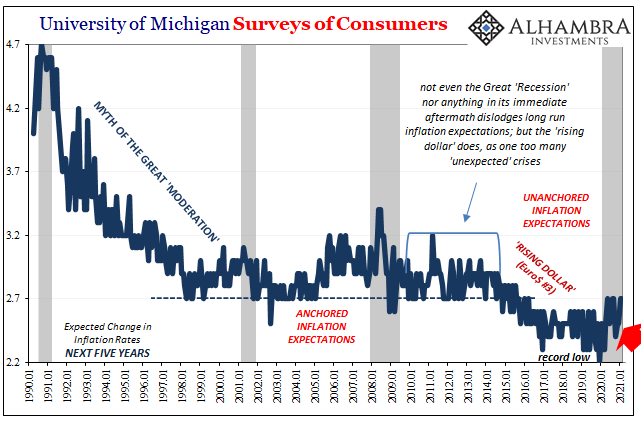

And even then, not as definitive nor impressive as “highest in years” might otherwise make it seem. Longer run expectations, those derived from the same UofM survey, stuck at 2.7%. In other words, those picturing inflationary conditions for these college-based researchers can easily tell them that gasoline prices are rising now but might not stick around very long at the same rates of change.

The inflation Powell and the Economists who follow him seek isn’t this; rather, it would be sustained accelerating consumer prices including but by no means limited to oil. This would have to be broadly, not narrowly, based and it would be accompanied by dramatic labor market improvement required underneath to create it and make it widespread enough to take up so much remaining slack.

It is, for now, at least the one datapoint better than the alternative indicated by the CPI and PCE Deflator. And the interpretation it might offer is not being shared by these same surveyed consumers. When it comes to their overall economic expectations, which include their views on consumer price pressures in the future, Americans aren’t in a very positive mood whatsoever.

The UofM index of sentiment dropped slightly in its updated figure for this month, falling to 76.2 from a revised 79.0 in January. Looking ahead, the index for consumer expectations fell more, down to 69.8 from 74.0. Both February readings are the lowest since last August. In truth, they aren’t much or any different despite all that’s “gone right” over the many months in between.

And that includes, of course, not just vaccines but also one round of further “stimulus” ($600) in addition to Powell’s (forever) ongoing QE6. With the promise of yet more Uncle Sam payments in the near future, the UofM is somehow puzzled to find fewer consumers thinking positively about so much massive support.

Consumer sentiment edged downward in early February, with the entire loss concentrated in the Expectation Index and among households with incomes below $75,000. Households with incomes in the bottom third reported significant setbacks in their current finances, with fewer of these households mentioning recent income gains than any time since 2014. More surprising was the finding that consumers, despite the expected passage of a massive stimulus bill, viewed prospects for the national economy less favorably in early February than last month. [emphasis added]

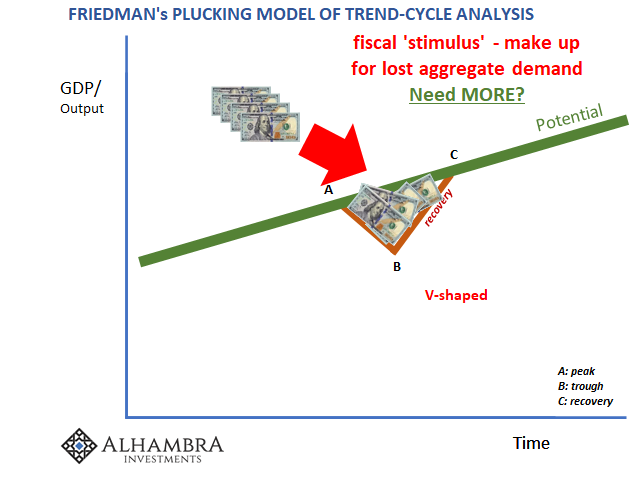

Surprising to whom? Economists, surely, who view the economic situation as nearly recovered (unemployment rate view, again) thanks to QE’s highly “accommodative” stance so more so in danger of overheating.

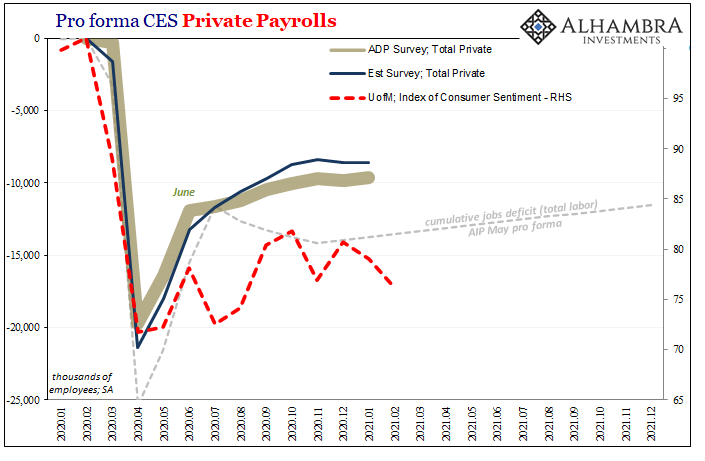

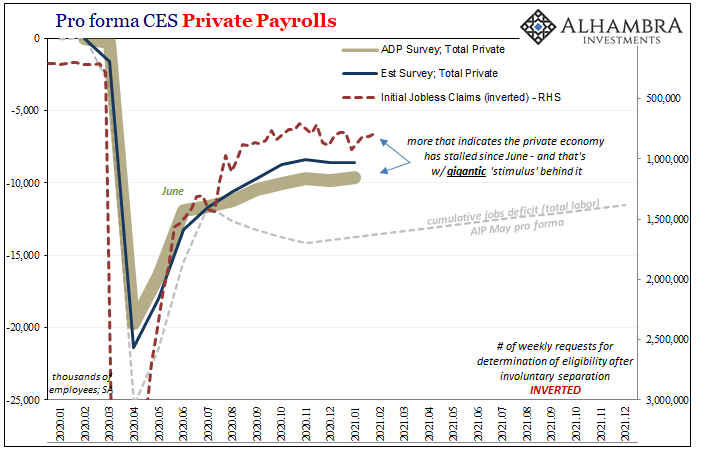

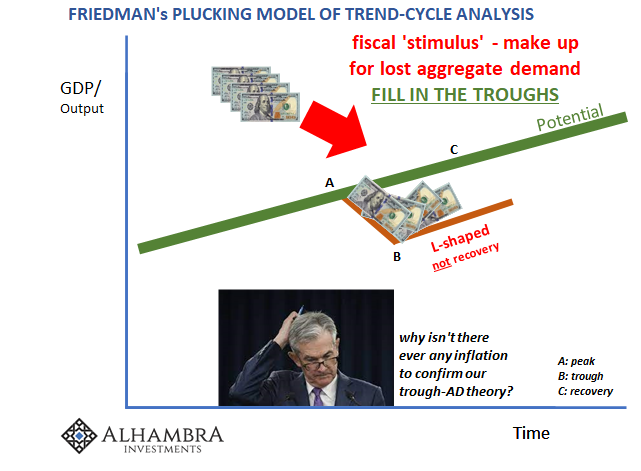

Outside academia and chalkboard equations, consumers are – quite rightly – setting aside gift horse Biden rather much more concerned about the very real, very disastrous employment situation which was not, despite last year’s promised “V”, considerably different. Sure, reopening in May and June led to a significant number of jobs coming back, but then…

While the mainstream inflationary view dismisses the permanent income hypothesis, treating all fiscal spending as if the perfect substitute “aggregate demand”, consumers outright stated at least to aspiring Michigan student economists they don’t agree. Stipends are something, perhaps necessary, but nowhere near sufficient.

Jobs. Jobs. Jobs.

The Treasury Department can send everyone huge checks and electronic deposits out of its TGA (while refunding T-bills in deflationary fashion), these tens of millions of concerned workers and former workers understand very well that transfer payments don’t equate to solid employment. That is what matters – in reality as well as the inflationary check on what reality must actually be.

Not forgetting like most conventional forecasts, “stimulus” in 2020 only left the employment market in this awful shape – a more than legit employment crisis that has now spanned almost an entire year and remains the most significant challenge since the Great Depression. Stocks at record highs mean nothing in this state (except fueling further resentment over class divisions, exacerbated by the Fed which appears to be bailing out a protected class of the wealthy).

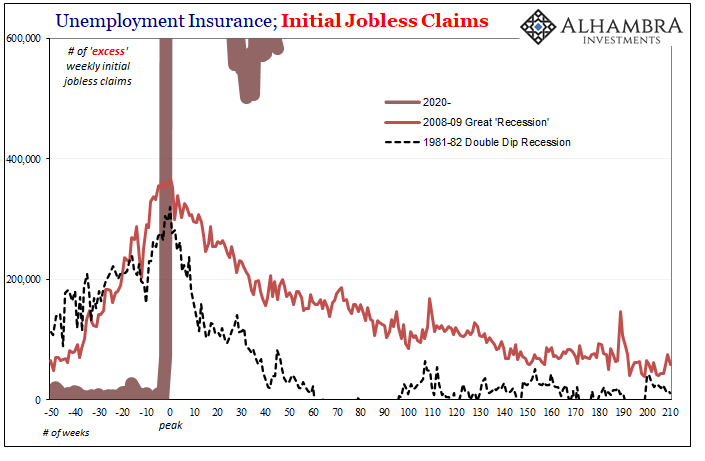

Would anyone have ever believed back in March 2020 that for the next forty-seven weeks initial jobless claims would remain, each and every week, at tallies greater than any other week in history before then? Forty-seven straight weeks – and counting.

Jobless claims last week, the week of February 6, were still just shy of 800,000 (and barely show up on the chart above). We’d never even had so much as 700,000 in any single week before last year.

The government can offer significant aid to alleviate some of the damage done by this level of employment crisis, but, no matter how forcefully the media and Economists claim otherwise, it cannot erase it. The more time passes, the more this becomes true. That much had been proven and established, for the second time in recent memory, during 2020.

Jay Powell’s inflation claim is staked on the idea that we’re almost there, almost back to recovery. Consumers/workers absolutely know better, and aren’t looking at gasoline prices for some positive signal of better days ahead. More like making it harder than it already is. While there had been some government-fueled gigantic positives in the middle of last year, the only thing gigantic at its end, and six weeks into the next year, continues to be slack.

Stay In Touch