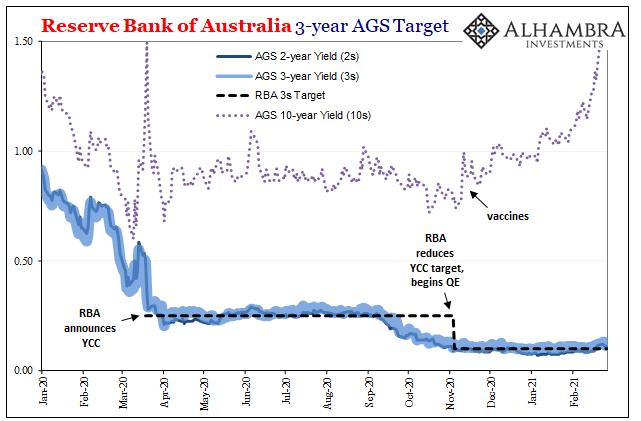

Australia, by contrast, now that’s becoming a proper bond rout. While the country’s central bank clings to its yield curve “control” fantasy, the long end of the AGS curve has gone true vertical. Yielding as little as 1.04% just four weeks ago on January 28, the rate for that country’s 10-year government bond has added an impressive 83 bps in the 21 trading days since.

More impressive still is how the market really hasn’t budged all that much so far as interpretation might be concerned. This was a universal problem especially back in 2017 and 2018 (like 2013) when the so-called Bond Kings were reported to have been speaking for the market as a whole; they never did. While they may have been – as they always are – bearish, globally sovereign markets didn’t really shift perception all that much.

In the media, rising nominal rates were spliced together with Bond King pronouncements to make what seemed a compelling case – that didn’t really exist.

This is also true right now; while much of the mainstream has been hysterical surrounding the past few months in bonds, even in Australia “the market” has kept its head.

“The markets are wrong” about inflation expectations, said Sicilia, chief investment officer of the A$56 billion ($43 billion) Host-Plus Pty pension fund in Melbourne. “Deflationary forces are bigger. Interest rates are going to stay at effectively zero.”

I think that’s a bit too harsh, too conclusive, and therefore too much like convention which likes to make this bond business into an exclusive binary: when yields rise, we’re told that can only mean the market is getting onboard with inflation; when yields don’t rise, they’re just waiting for the day until they do.

In other words, apologies to Sicilia, they are not “wrong” now even if you believe that inflation has little to no chance. The selloff in Australia’s long end is a good example; out of any national system’s, Down Under would benefit most from what commodity prices are managing right now. That’s why the AGS 10s are underperforming pretty much everywhere else.

And yet, despite this big move up in long yields it only rearranges the picture somewhat. The market hasn’t become conclusive about inflation and growth, the probability spectrum has become less pessimistic when compared to the end of last year, even the end of January this year. This isn’t the same thing, and therefore it’s not that the market is “wrong” or potentially so, rather a small change in probability that is being interpreted like a Bond King might.

One key reason for why this difference, “deflationary forces are bigger.” This view applies not just to Australia’s piece of the sovereign action, even more so elsewhere where the bond “rout” so far deserves every bit the quotation marks. Unlike the often-hysterical certainty about inflation, bonds have seen all these things before – repeatedly.

It always ends up in the same way, too; which isn’t the preferred central bank way. Yields can be interpreted best in this manner: in late January, AGS rates suggested a high degree of skepticism about the RBA’s policies as well as monetary and fiscal interventions around the world. During February, with commodity prices screaming higher, the long end AGS shifted to become somewhat less skeptical and mostly due to COVID vaccines.

That’s it.

The bond market globally knows central banks are all smoke and mirrors, but as to what really thwarts them, what is it that is and has been really deflationary, this much remains a mystery for anyone on the outside to attempt to explain. Economics as a discipline has left the public and even most participants entirely illiterate.

Like Sicilia, [Michael] Clavin [head of fixed-income at the A$140 billion Aware Super] points to technology advancements as the biggest damper on long-term price growth.

Economists have struggled for years to quantify technology’s deflationary impact on everything from supply chains to wage growth — Clavin’s wind vane for price pressures — but the overall effect has been to stifle price increases. And that’s not including the increased unemployment from the pandemic.

Can the “good” deflation of productive advancement really be the reason “monetary inflation” hasn’t been seen anywhere since 2008? Of course not; had it been that way, economic growth over the period in between wouldn’t have been so uneven (at best) to nonexistent (more accurate). You have to have legitimate growth to have produced good deflation.

So, in this instance, we’re at least halfway there; for once, admitting that the overall bond market – even in Australia where the latest selloff has been strongest – continues to be highly skeptical about all this global inflation certainty. History and the evidence demand nothing else.

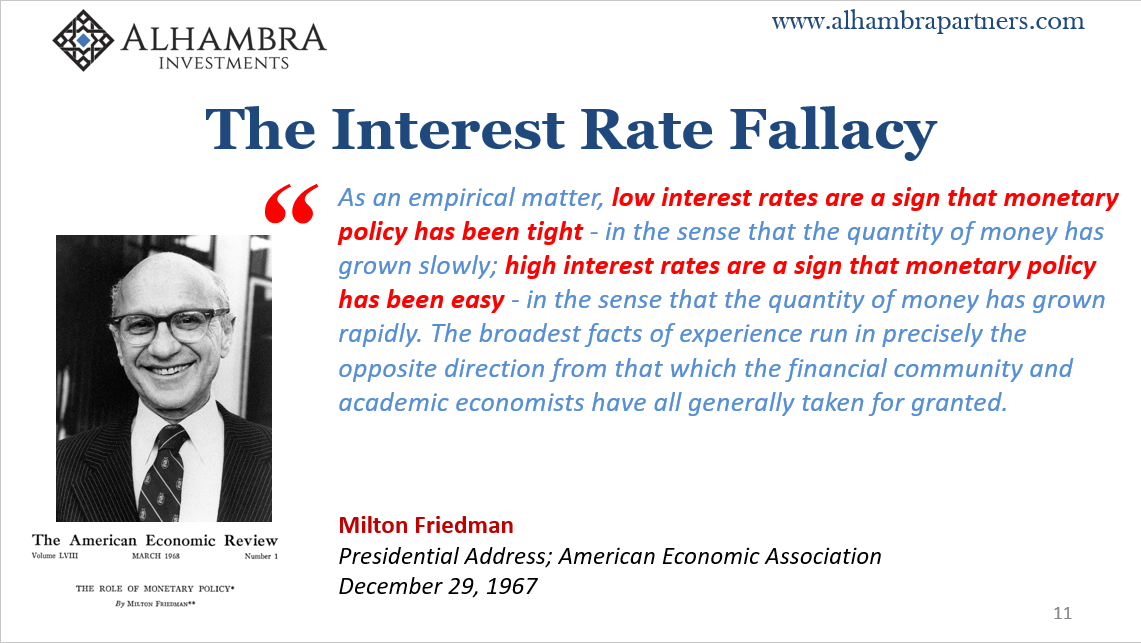

But why this has been, and likely will be, the problem remains with Economics; as in, how mainstream convention about interest rates that’s where it has been all wrong in its binary outlook.

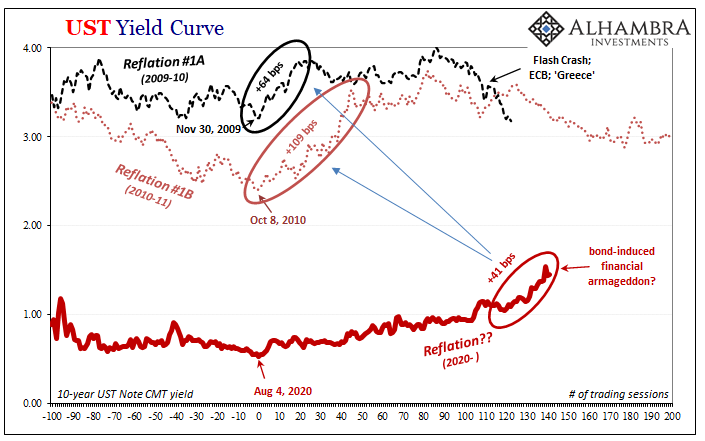

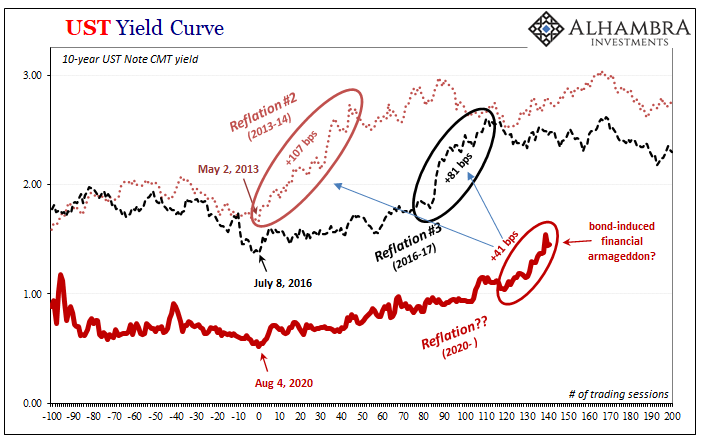

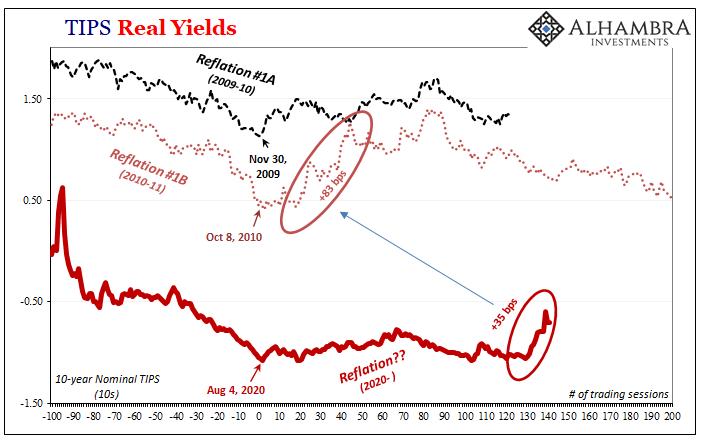

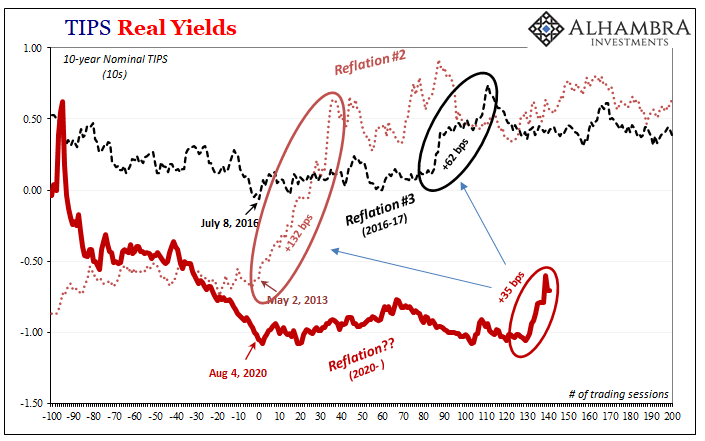

The problem hasn’t been “good” deflation, or good anything, just deflation. Both parts of the Australian bond market, even during this selloff, are unwittingly highlighting the key suspect; the central bank doesn’t control what it claims to control because it central banks don’t actually do what they say they do. If you’re wondering why there hasn’t been inflation and why bonds, even Treasuries (look at the current situation when compared to prior reflationary periods; not even close to those), right now aren’t really convinced (nor convincing) about all this “money printing”, look no further than rates themselves.

Stay In Touch