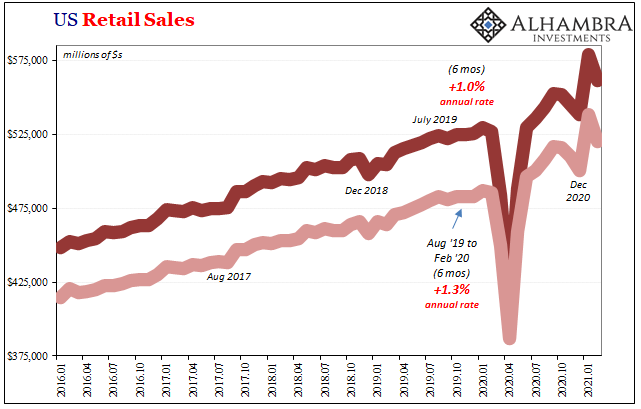

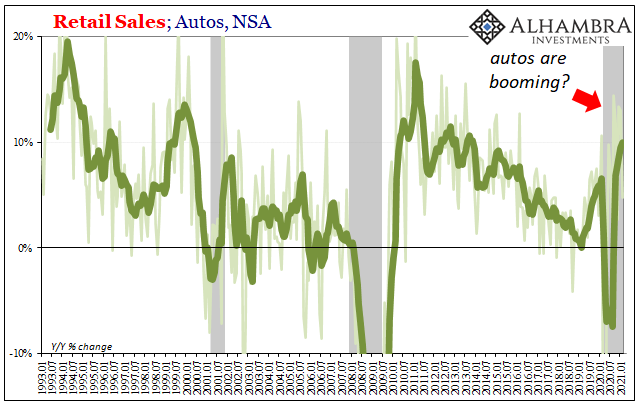

While the global inflation picture remains fixed at firmly normal (as in, disinflationary), US retail sales by contrast have been highly abnormal. You’d think given that, the consumer price part of the economic equation would, well, equate eventually price-wise. Consumers are spending, prices should be heading upward at a noticeable rate.

To begin with, consumer spending – as pictured by the Census Bureau – was obviously boosted during January by the previous infusion of Uncle Sam’s beneficence (he’s your “uncle” and he has the cash). By how much, though? According to preliminary estimates released last month, for the month of January it must have been a lot. The latest update for February, which includes revisions to January, maybe it had been even more.

But then a lot less.

Meanwhile, December and the all-important Christmas shopping peak continues to go downward.

Wild swings in both the data as well as revisions to it are not normal.

Let’s back up a minute first to go through the numbers: last month Census pegged total retail sales at a seasonally-adjusted $568 billion for the month of January 2021. That was up an enormous 5.5% from (first revised) December 2019. Right now, however, the government thinks sales in December were ~$2 billion less than that but in January they had been $579 billion rather than $568 billion (an incredibly absurd 7.6% monthly gain).

Following, though, in February, total retail sales are now back down to $562 billion, an uncharacteristic month-over-month decrease of more than 3% from January’s revised number.

In other words, not only are retail sales all over the place, the Census Bureau is seemingly having trouble keeping up with so much spending volatility. And this level of instability, particularly predicated on non-economic factors such as Congress, is highly abnormal.

Sales that were falling rather sharply to end 2020 suddenly surge to start 2021 if only because the previous federal administration left a parting gift for the public only to drop sharply yet again as the same public can only bide its time (and its wallet) until the succeeding federal administration tries to outdo its predecessor. Come to think of it, the lack of consumer price inflation – even in the goods sector – actually does make sense.

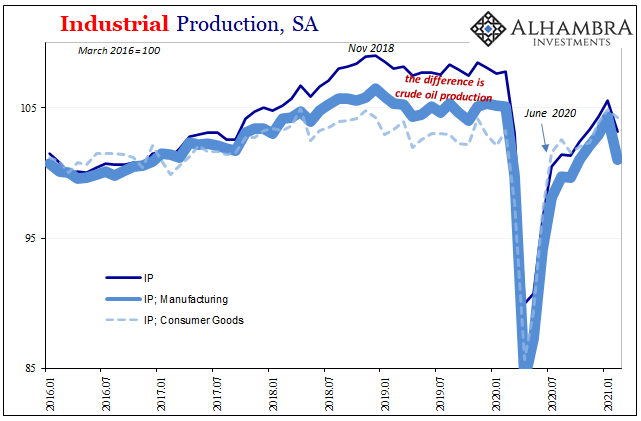

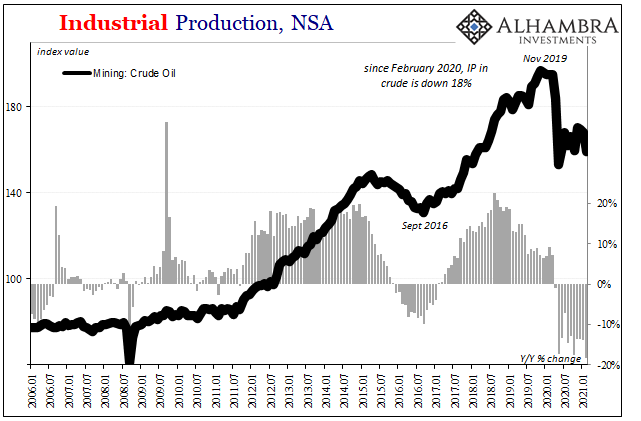

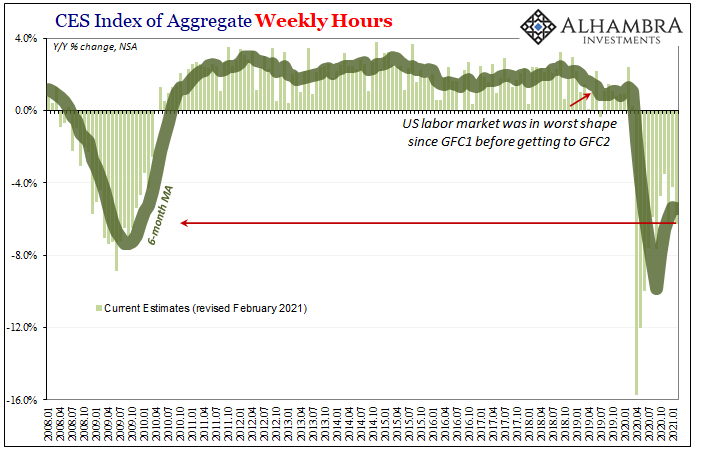

As would what’s shaping up on the production side of the economy. Contrary to many mainstream assessments declaring the US system to be “blistering” or “scorching”, actual producers and their production levels linger instead as subdued, constrained, and depressed (in every sense of the term).

Perhaps because of the wild swings on the consumer side, maybe in spite of them instead looking longer-term, according to the Federal Reserve’s estimates for Industrial Production the goods economy took February off, too. Having only rebounded modestly (like employment) since last summer, production levels also fell sharply last month.

Overall IP was down 2.2% in February 2021 when compared to January, which represented a recession-like 4.2% lower level versus February 2020. And it was domestic manufacturing which brought down total industry; IP Manufacturing dropped 3.1% month-over-month as US goods producers backed way off even though production levels still haven’t normalized to pre-COVID times (which were already significantly less than the peak all the way back in late 2018).

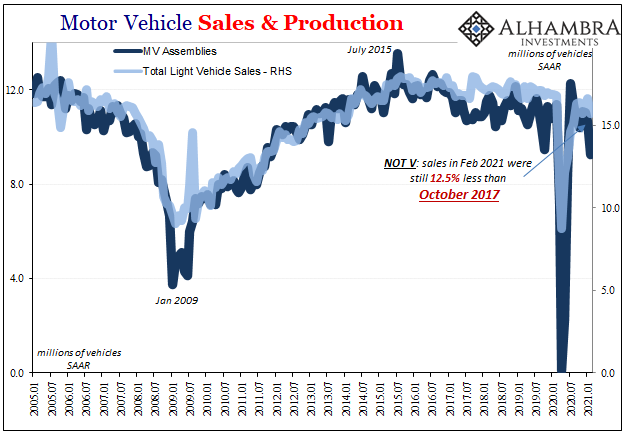

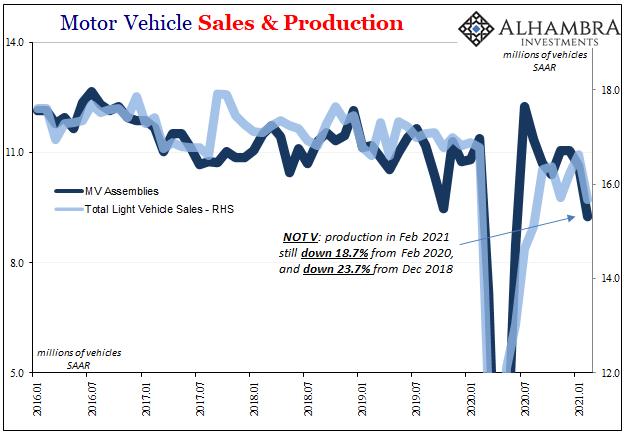

Of manufacturers, the weakness again had been attributable largely to automobiles. Domestic motor vehicle assemblies apparently crashed during February; down an enormous 13% from January, this translated to a seasonally-adjusted annual rate of only 9.2 million. Not only was that the lowest output level since last June, it was nearly 19% less than February 2020 (and down nearly one-quarter from December 2018!)

This is supposed to be a robust, inflationary recovery being led full-tilt by “stimulus”-fueled consumers especially in the auto sector. Why aren’t producers, literally, buying it?

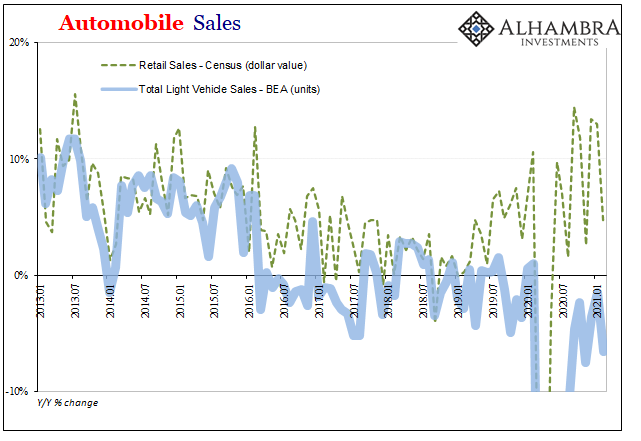

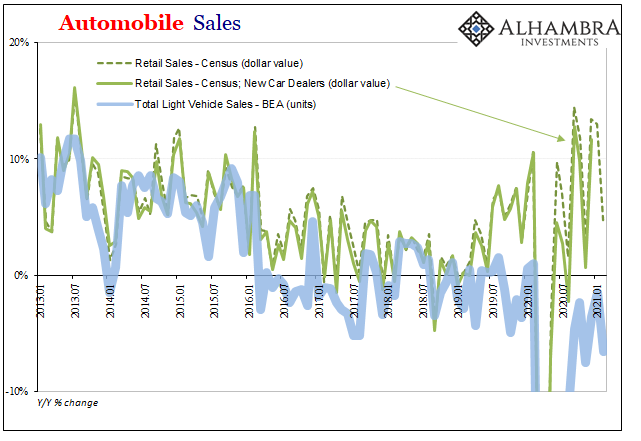

Instead, we find again how there remains this enormous discrepancy between what the Census Bureau says is a truly robust recovery in auto sales and what other agencies in the government think of the same exact part of the economy. As we’ve noted for some time, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA; the folks who put together the GDP data often using Census’ figures) calculates falling not rising sales activity.

While the one, Census, estimates dollar values of autos sold (and includes used vehicle sales), and the other, BEA, counts only new units, the difference between their approximations has never been wider. Neither used vehicle sales (you can see below that retail sales of new car dealers matches the trend for the overall total) nor per unit price hikes can account for what is now a huge chasm between what should be, and had been up to the “recession scare” in mid-2019, corroborating datapoints.

Census (retail sales) believes the dollar value of auto sales were up 4.7% year-over-year in February, which was actually the lowest in some time given the 6-month average is now 10% (including February). The BEA, by contrast, figures there were 6.6% fewer units sold year-over-year in that same month, February, dropping its 6-month average to -4.3%. One says robust recovery, the other languishing in deep recession.

The BEA’s series seems far more consistent with the Fed’s data on production.

And if that is true in just the vehicle segment, might it also be true in more widespread fashion given 1. CPI or PCE Deflator inflation numbers that continue to be historically low; 2. Commodity prices rising only because supply stays restricted or curtailed (suppliers don’t seem to be in any hurry to chase rapidly rising prices; see: below, IP crude oil); 3. The Census Bureau seems to be having an awful lot of trouble figuring out just how much retail sales are and have been, so you can imagine that maybe producers are having trouble with what they think, see, and plan; 4. Volatility in consumer spending regardless of the government’s inability to pin it down accurately isn’t conducive to producer-led recovery processes – if you can’t count on consumers because they’re counting mostly on the government (at the margins), that’s a whole other set of risks keeping a lid on the rebound/recovery.

This is not an indictment of the Census Bureau, nor does it any way indicate some conspiracy to inflate estimates on behalf of whichever postulated political beneficiary (especially since the auto discrepancy, at the very least, has crossed over administrations). My point is simply this: these are and remain abnormal times. That is why retail sales estimates are wildly all over the map, and why very likely consumer spending really is, too.

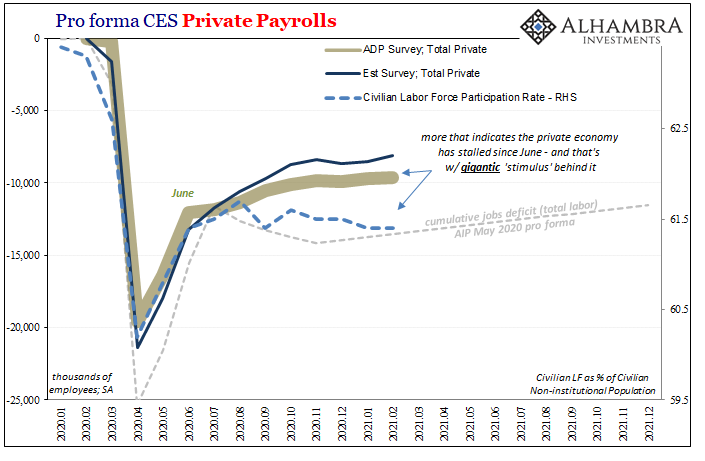

Recoveries, real recoveries, aren’t like this. Thus, the further you pull back away from the marginal volatility where it logically manifests (given the labor market’s huge setback and how it is government spending attempting to bluntly offset it) the more economic (not COVID) factors related to depressed levels of overall economy make sense.

Producers have certainly noticed the abnormality, and what’s driving it, left to judge the (high) risks of being caught overextended betting on renewed normalcy at some point that even after a year has clearly been elusive – both in data as well as in a very real, real-world sense. Governments can try to offset this hole, but they can never really fill it in.

Stay In Touch