In theory, it goes like this: QE or any sort of large-scale asset purchase (LSAP) undertaken by a central bank is needed during times of trouble in order to reduce interest rates in general. Buying bonds seems like it would lower yields, and lower yields mean more accommodative credit, therefore a boost to the real economy.

So simple, straightforward, and intuitive, who could possibly argue otherwise?

And the theory has been studied (to death). Ever since the Bank of Japan pioneered this quantitative method of monetary policy, there’s now two full decades of experience with it being employed (since 2008) in wide a variety of global jurisdictions. The cumulative evidence does point to the conclusion that this technique does appear to reduce interest rates.

Sort of. Here’s what, oh, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) has to say about LSAP effectiveness:

When we buy assets, this increases their price and so reduces their yield. That means the interest rate, in this case on government bonds, fall. This has the effect of ‘lowering the tide’ on other interest rates in the economy, particularly longer-term interest rates of two years or more. It also reduces the cost of borrowing for households and businesses…

LSAP programmes have been conducted in the euro area, Japan, Sweden, the United Kingdom and United States.

The evidence shows LSAP proved effective in providing much needed support, lowering long-term interest rates and exchange rates, and underpinning economic growth and inflation.

Studies found the government bond purchases worth 10 percent of GDP have, on average, lowered 10-year government bond yields by around 50 basis points. [emphasis added]

It’s true; many academic studies from around the world focusing on different program types in different places have come to similar conclusions using all kinds of regression analysis. They find that QE programs do correlate with falling interest rates; maybe even “around 50 bps” (the “around” part means rounding up).

Even if we take them at their numbers, and presume correlation equals causation (because, they’ll tell you, they do account for the difference when regressing variables), you should still end up wondering why they even bother with this stuff.

Purchase bonds equivalent to ten percent of GDP, and rates are at most half a percent lower?

Talk about underwhelming; not exactly the powerful printer, the massive “accommodation” and “easing” told about in every mainstream media article on the subject. In fact, you’re probably already putting those 50 bps into context of, say, the United States’ experience; the 10-year UST yield had been “around” 4% when Ben Bernanke’s Fed cranked up QE1 in December 2008 (down from around 5% as things really got started the year before) and are today less than 1.75% today (and that’s being talked about as some ginormous financial hurdle).

Of that ~225 bps decline over the years, a lot less than 50 bps of it is QE (the Fed just reaching the 10% threshold recently, and that’s cumulative for all the years of it). And it’s really more like 325 bps since 2007, and top to bottom just about 450 bps. Barely much of it comes out in the most favorably set up mathematics to be arguably “caused” by the Fed’s LSAPs.

In short, the market itself has done far, far, far more where interest rates going lower have been concerned. That seems pretty important, don’t you think?

The official response – in public – is that, yes, rates have dropped on their own but QE made them go (a relatively tiny bit) lower than they otherwise might have. This is the monetary policy equivalent of “jobs saved”, a manufactured counterfactual attempting to salvage something more relatable (to the average person) than the even-more-made-up term premium argument.

In private, even authorities know this doesn’t really fly. Cue up Richard Fisher (of all people):

MR. FISHER. In summary, I want to mention that, as I said earlier, most of these variations that have been suggested are very un-Bagehot-like. And what I mean by that is, twisting [or QE and yield caps] entails purchasing assets that investors are fleeing toward, not assets that they are fleeing from. [emphasis added]

This is no mere trivia, figuring out who, what, and, most important of all, how bond yields and interest rates are actually determined therefore what they really mean means the whole ballgame – that part the central bankers got right. What they get wrong is, basically, everything else. Who: market; What: rising not falling liquidity risk; How: things like repo and global money.

The central bank and its QE’s are pure fiction; a puppet show for your amusement to distract you (and everyone else) from the fact there’s no real money in monetary policy. Furthermore, it is the market driving down market interest rates which proves this point!

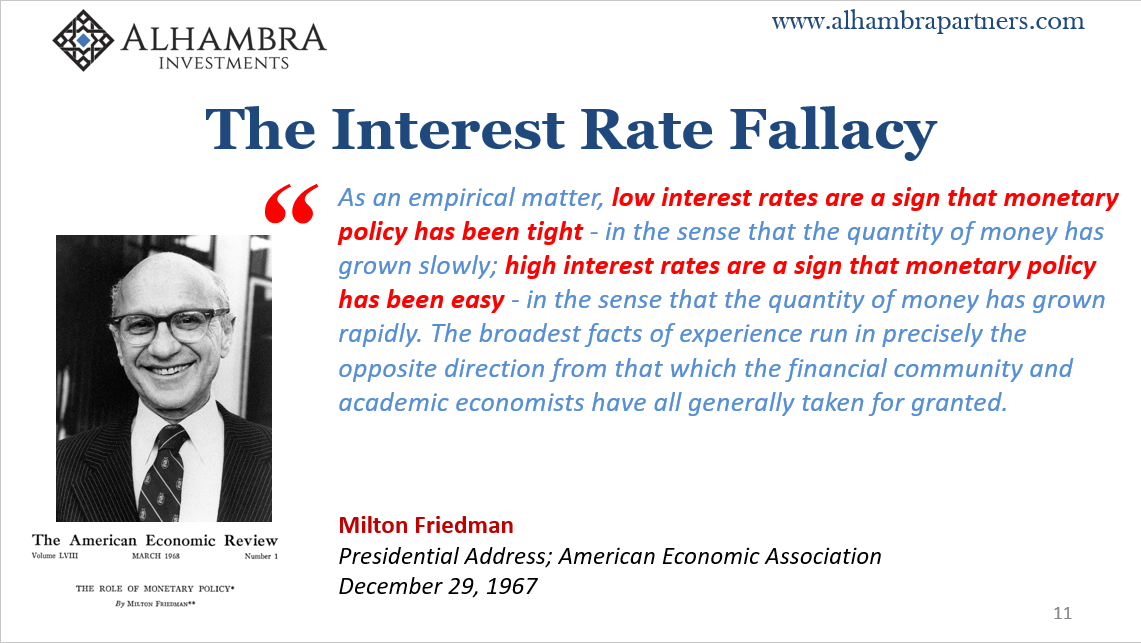

The interest rate fallacy may be the closest thing to immutable truth what little of value is left of Economics.

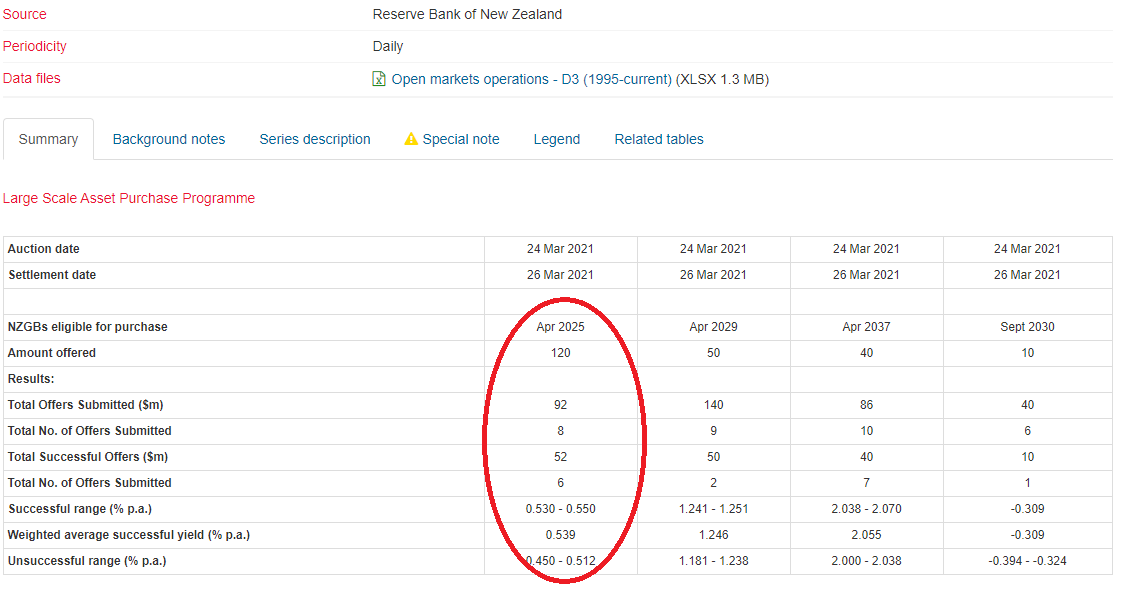

Choosing RBNZ’s choice words on the QE matter wasn’t random on my part. Earlier today (h/t Zerohedge), the country’s central bank published details of its latest LSAP transactions which included a very “busted” operation; the bank declared its intention to buy NZ$ 120 million government bonds (April 2025) from domestic banks only to find NZ$92 million in offers, of which only NZ$ 52 million were accepted.

You’d think a “busted” QE might allude to exploding yields in New Zealand’s government debt market, but quite the opposite. Rates across that country’s curve plummeted in today’s trading. They’ve been moving lower for weeks.

Yet, according to the mainstream, conventional view, this is where QE is supposed to show its true value. For several months now, yields in NZ like those around the world have been gripped by reflationary optimism – which each global central bank is forced to mischaracterize by its determination to hold steady to the QE theory that gets everything backward.

So, conventional thinking, rising rates and QE are right now in NZ needed most to keep them in check otherwise they spoil the recovery. In this case, however, QE is demonstrably superfluous because the market has been buying and doing this for several weeks already – to the point that, in one operation, banks don’t want to sell to the central bank. They’d rather keep the assets for their own purposes. Even inflation-ist Richard Fisher understood this.

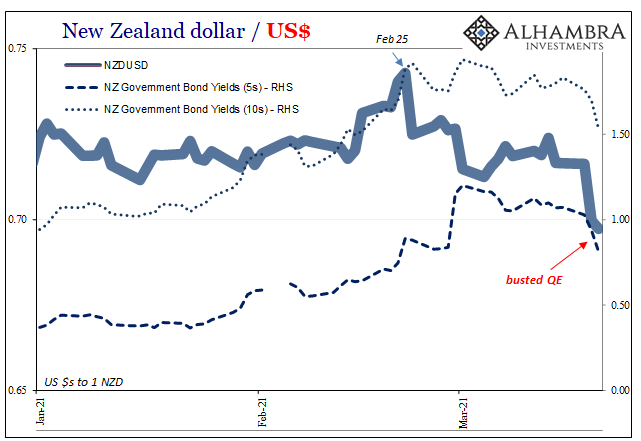

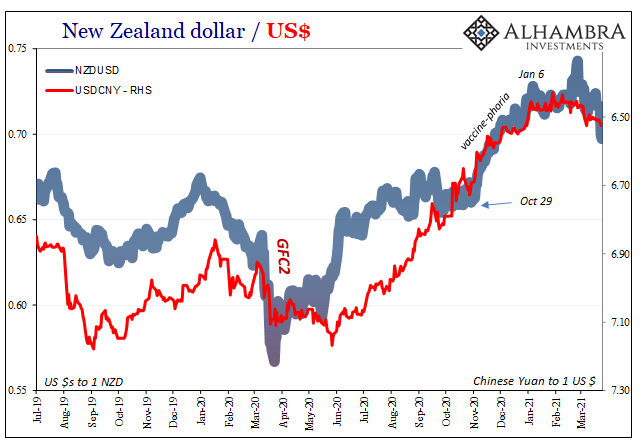

While a worthwhile review to further expose these QE fallacies, there’s more to it; a lot more potentially. New Zealand, like Australia and other parts of Oceania, is tied closely to the fortunes of the Chinese economy. What we find of interest rates in NZ is similar to the currency’s recent tendencies; reflationary for several months, but noticeably less so recently (since February 25).

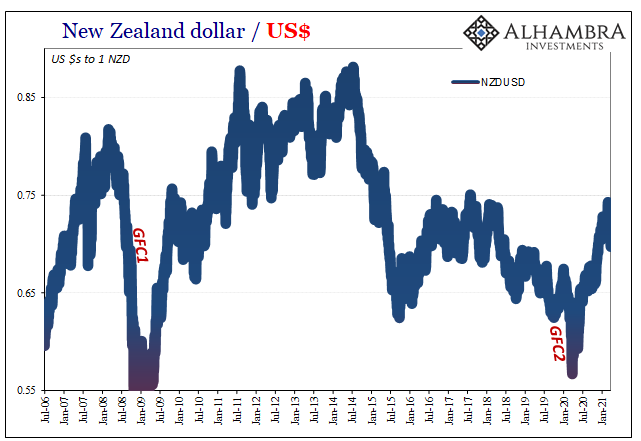

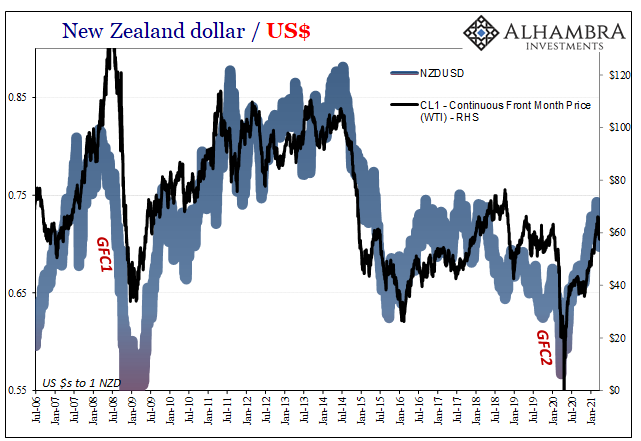

More than that, when you look at the longer-term (and even short run) chart of NZD against the US$, it should seem very familiar.

The generalized correlation between US$ oil prices and US$ exchange into NZD isn’t surprising given the connection to China via resources. Dollar financing, the dollar’s contribution to oil, and the eurodollar putting all the pieces together worldwide with the Chinese economy providing the planet’s central pivot for all those factors.

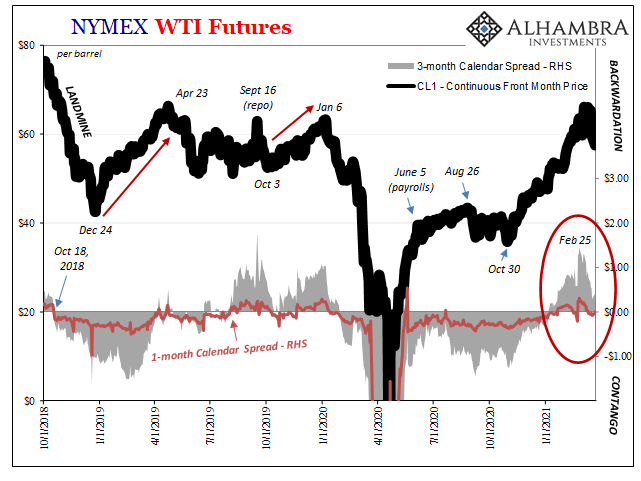

As noted yesterday and last week, “something” of late seems to have spooked the oil market which might also be attributed to negatives (rising perceived risks) in global money. Perhaps even more interesting, in a correlation kind of way, is that the level of (3m) contango in the WTI futures curve, a measure of reflation optimism in the physical as well as money realm, reach its absolute peak on…February 25.

Just like NZD.

It has been reflation-off in both ever since – even though New Zealand is hardly one of the world’s largest crude oil producers. If there’s a connection, it must be that “other” thing, the same factor which actually drives interest rates globally.

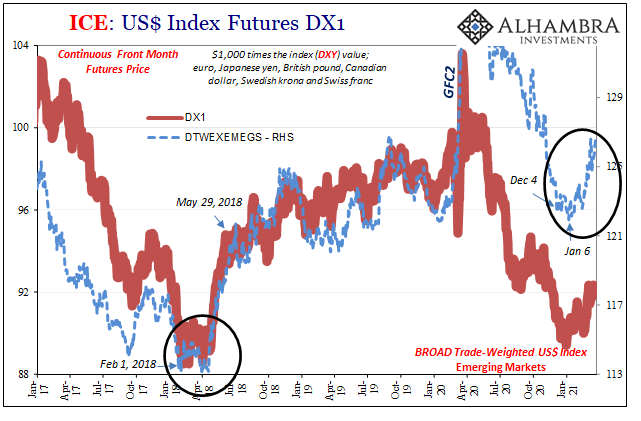

Eurodollars and the initial downside drag leading to havoc they often cause.

In this case, the other side of them showing up in China’s currency:

To build a little further on the growing theme at NYMEX with crude prices, there’s a growing sense of quite a bit more going on beside maybe profit-taking after oil’s huge runup. These are, right now, slightly more audible than whispers, but growing evidence of the possibility the eurodollar world is shifting. A, so far, small accumulation of small warning signs.

And China would be, for me, the big reason why. The world was told (by the QE people, so there you go) to expect big things from the Chinese while the Communists shook their heads back in bewilderment. Their economy isn’t doing all that well and authorities aren’t going to do anything about it because, and this is the whole point, it’s been proven to be pointless.

The eurodollar, global dollar shortage has demonstrated time and again to be unassailable through any means – especially QE. Instead, falling interest rates are both the curse and the proof.

At some point, Euro$ #5. Is this that point? Might February prove to have been the inflection point, a la February 2018? There’s not nearly enough time nor evidence to make that determination, though the sounds are becoming more familiar to that ear. Stay tuned to all the eurodollar channels, including those that might not immediately spring to mind. Kiwi QE relating to reflation, for one.

Stay In Touch