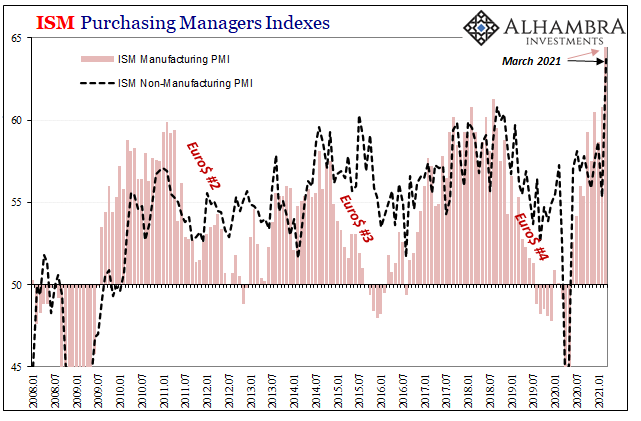

The sound of economic sizzle finally within earshot, though perhaps nearly a year too late. PMI’s for the month of March 2021 were of the sort which should have come about in May and June 2020. The “V”-shaped recovery was much talked about at that earlier time, though in PMI terms (as well as regular “hard” data) the numbers fell way, way short of it.

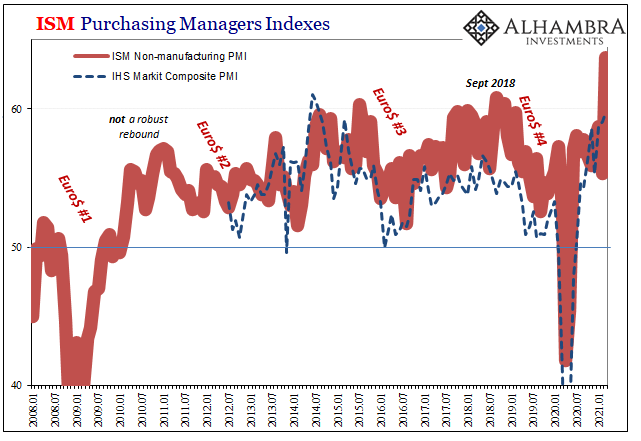

I and others had pointed out repeatedly that to be consistent with an actual recovery, given the depths from where the recession began, the indices really needed to get up into the high 60s if not low 70s. Both sets – manufacturing and non-manufacturing – for both of data providers – ISM and Markit – started out moving in that direction before falling off well short.

With (further) reopening back on the schedule again, plus Uncle Joe’s Uncle Sam $1400, US sentiment surveys finally soared last month – at least in the ISM versions. According to the latter, manufacturing pumped up to 64.7, rising just less than 4 pts; non-manufacturing soared 8.4 pts in March, reaching a similarly gaudy, just nearly V-like 63.7.

Markit’s take was hardly subdued, it just didn’t change all that much in March 2021 from February: manufacturing headline up to 59.7 from 59.5, though still a bit lower than the 60.5 in December; services rising to 60.4 from 59.8, the highest in nearly seven years.

These plus the near-million March payroll number, the US economy seems set finally to reach into that whole inflationary acceleration trajectory the world’s been hearing about – and counting on – for just about a year. Better late than never?

That’s the thing; as noted earlier today, everything seems to be lined up just perfectly. Vaccinations are rolling out, more states (even California) loosen themselves up, and the government continues to throw cash around to anyone who can breathe (and quite a few, apparently, who aren’t taking breaths). Trillions upon trillions before then Jay Powell and the Fed’s similar-sized puppet shows.

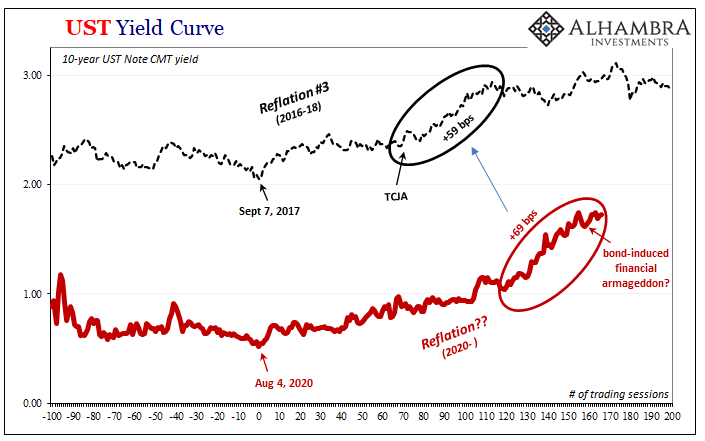

For a few months, there, even the bond market imagined how great this could turn out to be. Reflation, the more noticeable kind, materialized early in January and for almost two months it didn’t look back. As usual, the rise in rates triggered the hyper-response of BOND ROUT!!!! which, during this, again seemed plausibly plodding toward the long-promised inflationary (recovery) condition.

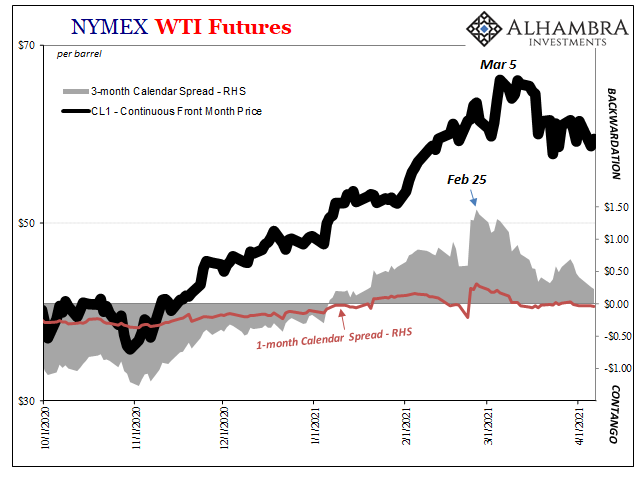

Funny thing, though, even as some of the data starts to obtain more “V”-ish properties for the first time, the reflationary markets may have gotten themselves out of it. This didn’t start in crude oil but the analysis of it really does.

There’s now contango in the front, the 1-month spread, and backwardation is nearly up at the very important 3-month interval (the most liquid contracts). Revisiting this theme earlier, I illustrated how those front contracts have been distancing intraday recently even more than indicated by closing levels.

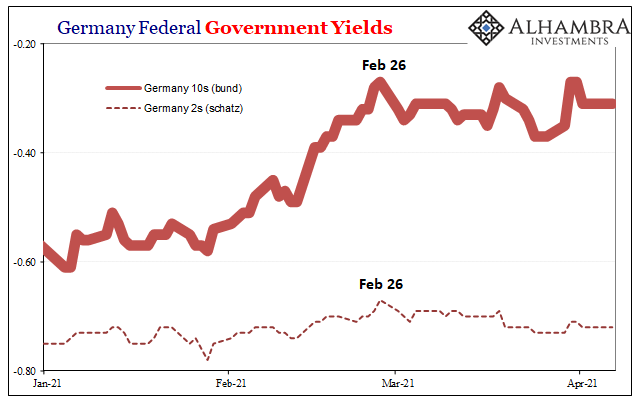

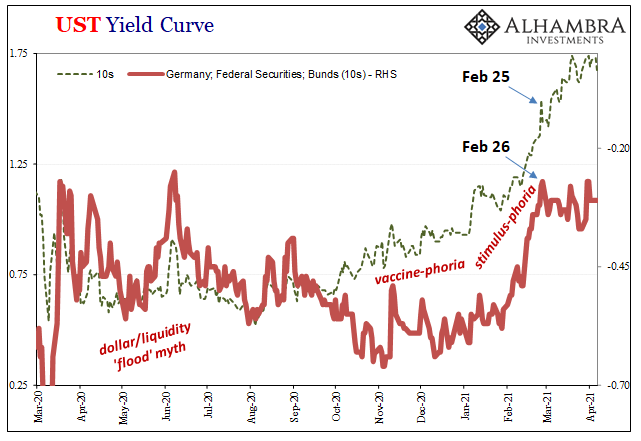

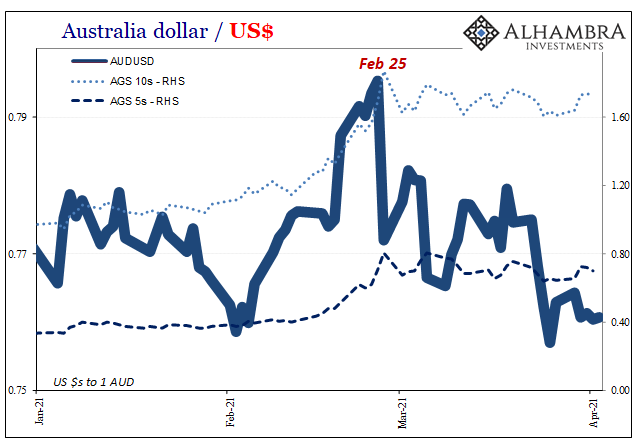

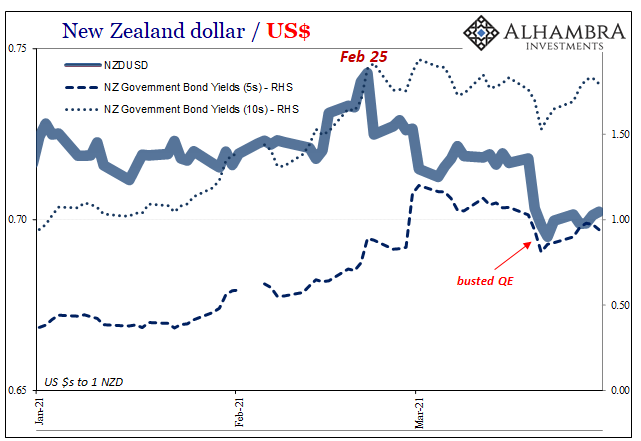

It’s not just WTI or even American/dollar markets; this late February shift has been almost universal. Go to Germany/Europe, bunds and schatzes break down (and out of reflation) at the same time (if a day later). They’ve been basically unmoved for six weeks now just as the data comes up more auspicious.

This seems to have represented another “decoupling” point from counterpart US Treasuries; bunds halted their selling while UST’s did not.

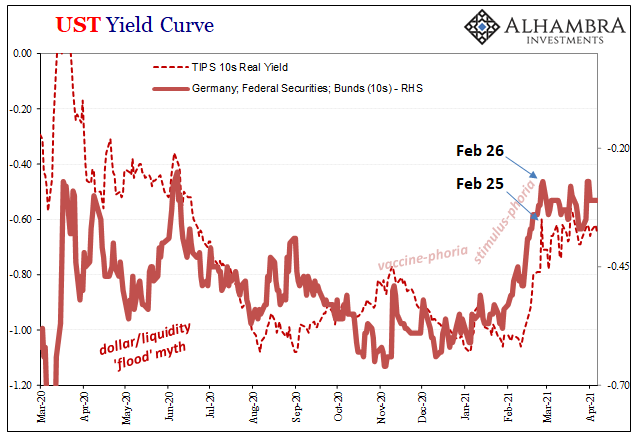

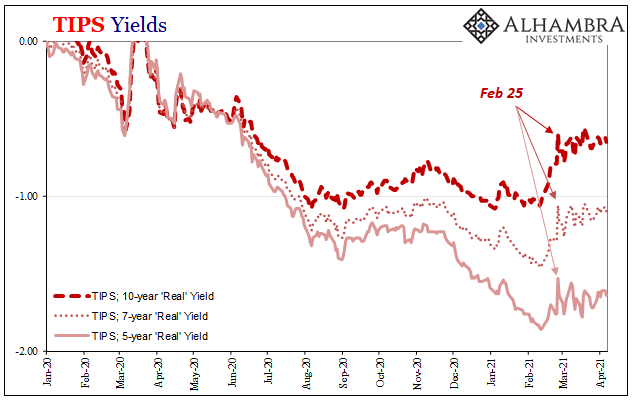

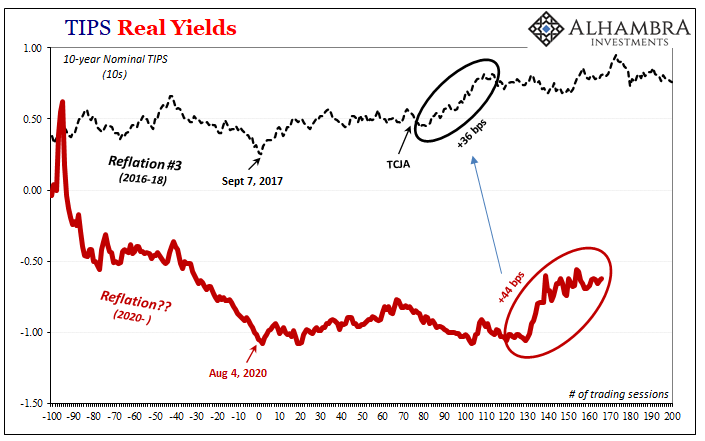

Or, at least part of the Treasury market did not. Nominally, yields continued to rise (though pausing now), while other segments have, in fact, matched Germany near perfectly. Which segment? Prominently, it’s the real yields (TIPS).

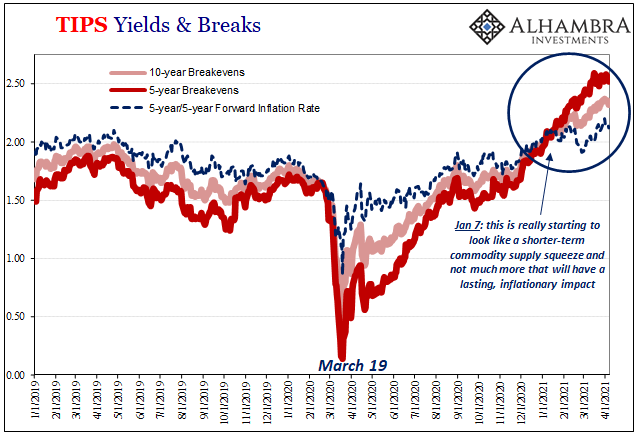

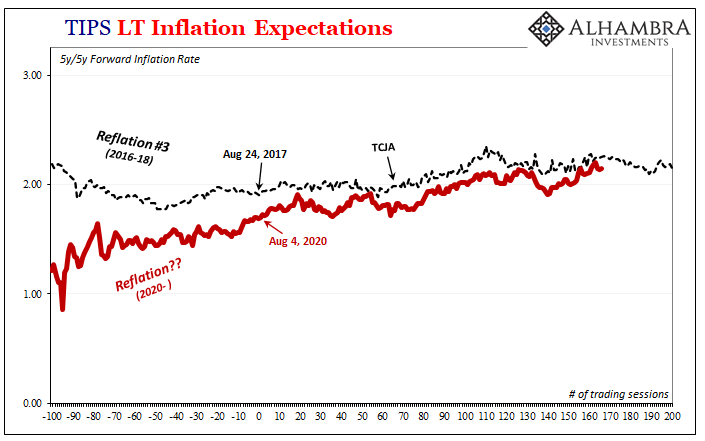

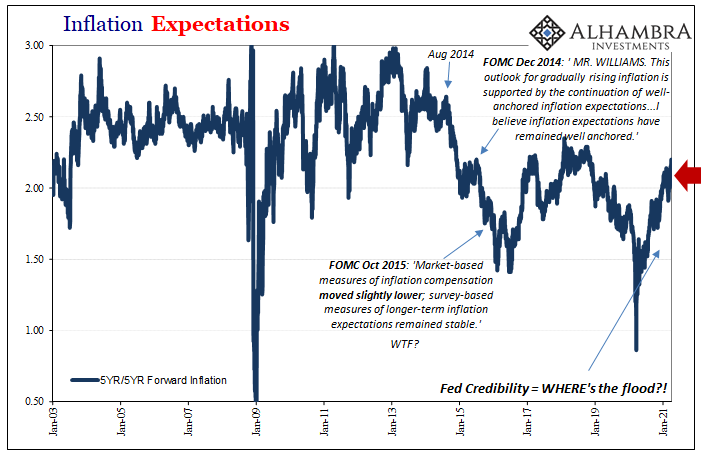

Now it starts to make more sense, especially when you pull up inflation breakevens derived from the difference between nominal UST’s and these TIPS rates. What I mean is, the inflation expectations part had sniffed out from the very beginning (of this reflation pulse) in early January the difference between short and long run impacts of whatever it is behind the general improving outlook.

Whether Jay’s puppets of Uncle Joe’s checkbook, vaccines and reopening 2, what that’s going to get us is a short run leap. But then what?

When real rates had been rising, too, along with nominal UST yields (or German bunds and the like) and therefore inflation expectations, that was the bond market in its entirety lifting its collective probability for the long run to something significantly less awful than it had been coming out of 2020. Big things in the short-term maybe could have had some lasting impact on the beyond.

The inflation expectations part of the market was more skeptical from the start.

Then February 24-26 seems to have triggered reconsideration. This is where it gets back to something like early 2018. Curves were up to that time pricing in a slightly better probability that the global economy would be able to soar; not a large probability or even all that much, but greater than near zero as had been the outlook closer to the start of Reflation #3 way back in the middle of 2016.

It was always priced for a far higher probability of souring even at the apex of inflation hysteria in early ’18; that there was too much of an ongoing risk of accumulating dollar problems which would end up derailing the entire global trajectory (globally synchronized growth) before it had a real chance to really dig in and get going.

Despite whatever attributed short run positives just then, including and especially the TCJA, bigger, structural, more meaningful negatives were in every likelihood too much to be overcome. Thus, rising nominal and real yields early in 2018 were together the whole market pricing a little more soar and a little less sour – only to turn back around later in the year with no chance for soar after having been completely overwhelmed by the increasingly sour (full-blown Euro$ #4’s globally synchronized downturn).

The transition between a little more soar and only sour was marked by a series of warnings and negative indications throughout the early and middle months of that year – from the dollar suddenly rising rather than falling to curves reshaping the wrong way, including May 29, 2018’s major outburst of collateral.

To put this into 2021 timing, from early January to around February 24, the market was near uniform in again repricing a little more toward soar, less sour. Then “something” happened at that moment which hasn’t yet moved the whole market back in favor of sour, but it has stopped the trend toward higher chances of soar across so many different markets – including the TIPS part of UST’s.

One of those warnings?

Two things immediately stand out about those particular days; violent Treasury selloff on the 25th, preceded by a Fedwire disruption on the 24th. Even if you don’t think the Fedwire trip would have been enough of a monetary disturbance, as I do, then the Treasury selloff would be remarkable for its own suggestiveness; if rising yields were what got the global market’s attention, higher rates being a problem, then what would this also say about the state of the global economy that it recoils at the mere sight of 1.75% or so long UST rates?

Either way, Fedwire or higher interest costs, both explanations lead to the same conclusion: a fragile system highly unlikely to weather some version of reality.

In other words, the market was shifting a bit toward longer run soaring on the promises (and now data) of short run factors like helicopter payments and such making for uninterrupted contributions, but then a possible financial warning around February 24 or 25 reminded it of the underlying baseline fragility which, if still material, would limit those factors (like in 2018 or 2014) to only the short run.

Thus, balance of probabilities, whatever happens positively near-term the chances of it lasting long and far we are reminded cannot be very good. The chances of, I believe, more (too many) eurodollar discontinuities over time.

The ISM’s figures may be “V”-like at last, now the world and its many markets appear to be seriously considering just how long it might last. More importantly, then what?

Stay In Touch