Silver linings have been hard to come by lately, especially last year. Twenty-twenty was a total washout in almost every way imaginable; and that’s an understatement. Still, there were some small signs of genuine progress such as Jay Powell’s thorough contribution to QE debunking. Bank reserves went sky high while practically nothing else did (other than equities), certainly not inflation.

No, if there is to be a breakthrough on that front it is widely understood to be Uncle Sam’s doing. All that bond buying by the Federal Reserve and the correlations all line up with direct aid to the economy, including helicopters. Fiscal has been the dominating factor at least so far as “stimulus” has been concerned. Aside from reopening itself, the details leave little doubt as to who’s really doing what.

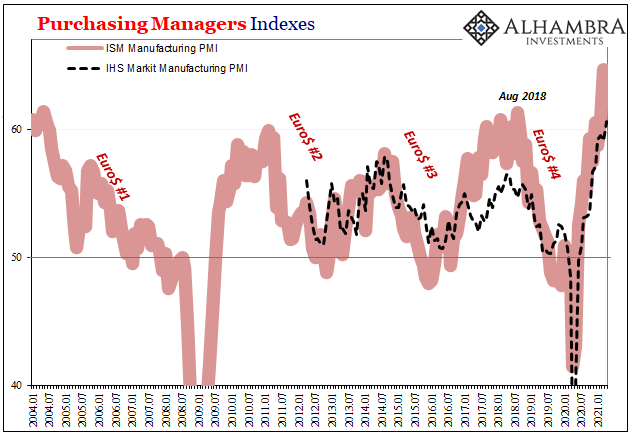

When IHS Markit reported its flash Manufacturing PMI estimate for April 2021 last Friday, at a record high of 60.6 its elevation as well as the way it achieved it could not have been QE-driven. Reopening plus Biden, these had been the impetus driving Markit’s big top (as well as the ISM’s for March reported earlier in the month).

Backed up by separate spending estimates, more so the volatility and when these ups and downs have occurred, it’s very consistent with the fiscal side rather than monetary.

Everyone’s big hopes, pinned in the form of inflation confirming them, reside inside the US Treasury. This is not to say Jay Powell is bitter; far from it, he still has the stock market with which to play “money printer” where unshakable belief is never in short supply. Here the Fed views its own contributions as indirect (record share prices, in theory, boosting consumer and employer feelings).

Given these facts, the Chairman like the Committee he leads has been both restrained as well as resolute on the inflation question. They keep using the word “transitory” and for the right reasons this time (unlike 2013-19; but very much like when former Chairman Bernanke used the same in 2011-12).

For one thing, maybe manufacturing really is booming, but why is it so incredibly robust? Record manufacturing PMI’s follow an insanely ridiculous burst of spending – quite evidently on Uncle Sam’s nickel.

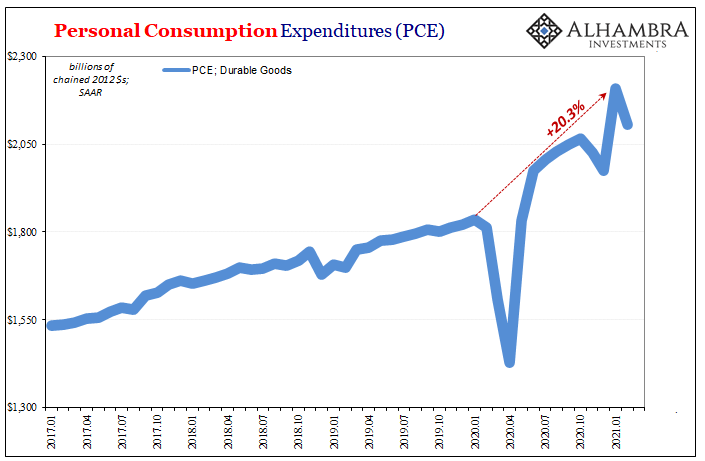

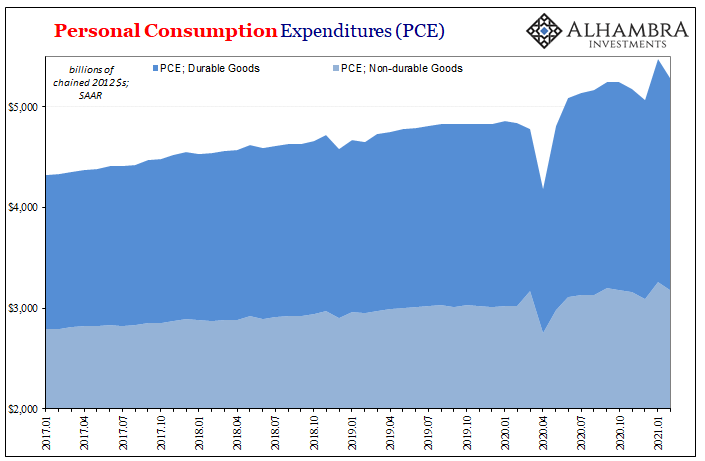

According to last month’s figures, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) indicates that consumer spending on durable goods, for instance, in January 2021 (Trump’s final boost) totaled a whopping 20% more than in January 2020. In February, the free-for-all (almost literally) declined somewhat but is expected to resurge even bigger in March (estimates to be released on Friday after the GDP numbers tomorrow). Some analysts think the monthly gain over February will have been 4% maybe even 5%.

Fiscal, not monetary. But, inflation question, is it really this easy?

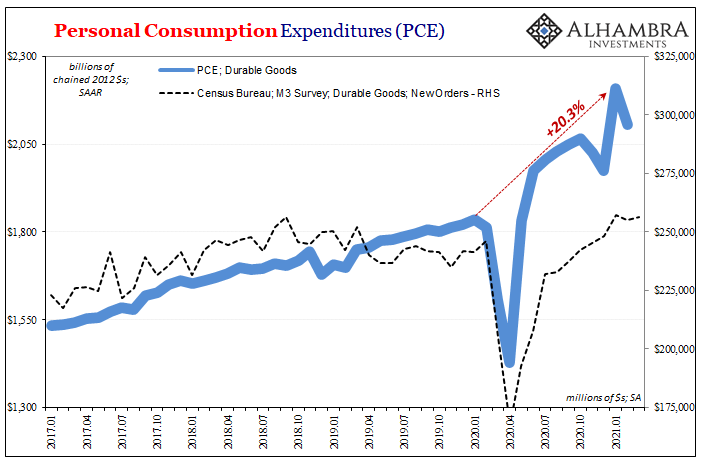

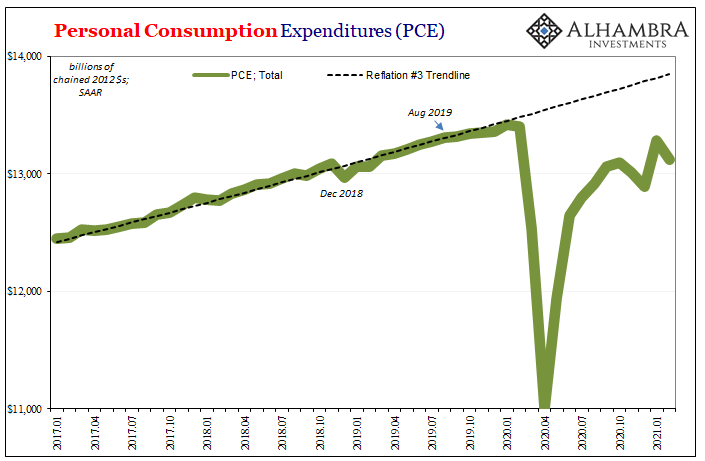

As we’ve been documenting since the reopening started, producers aren’t nearly so sure and that’s one key measure of uncertainty. The other side of transitory is “sustainable.” We’re mixing data series below (which you shouldn’t do) but just for illustrative purposes you can see the divergence (even if we don’t know precisely how big it might be):

Spending is way up but orders for new durable goods production are…not. They’re certainly up from the lows and at these levels are consistent with low to mid-60s PMIs but neither of them really with +20% spending. Unless that spending is also, like inflation in Powell’s mind, transitory.

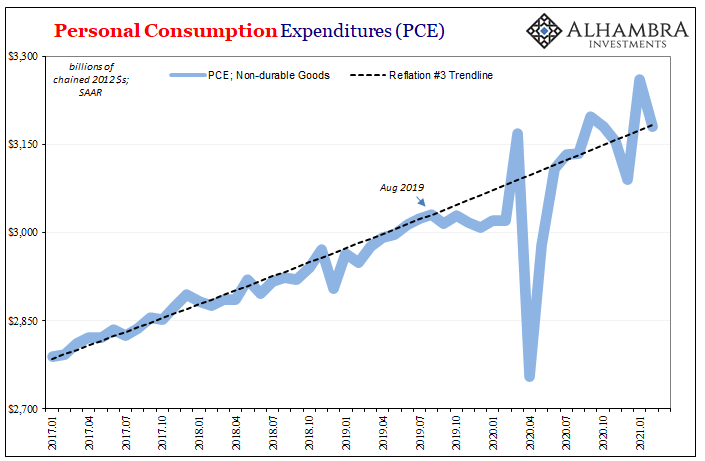

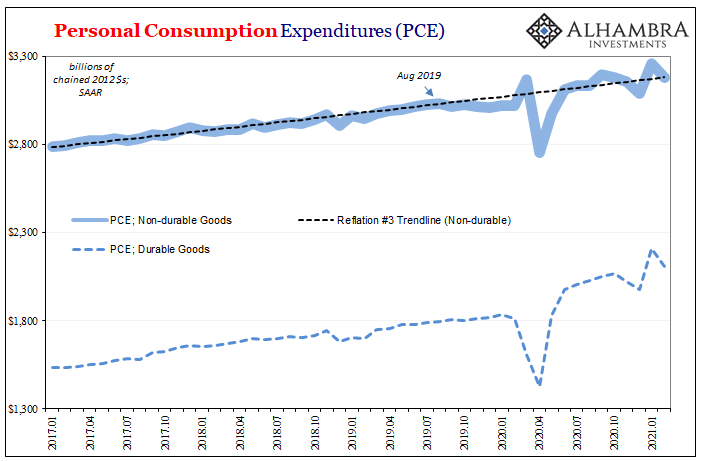

Durable goods are just one segment of the overall consumer marketplace, and the smallest one of the three headline components. Non-durable goods spending has been OK at times and then underwhelming at others; trending depending upon Treasury check writing. The net result of the resultant volatility is that consumers remain on track with the 2016-19 trend (Reflation #3) which wasn’t exactly all that great to begin with (therefore why there had been an inflation “puzzle”).

In short, Treasury’s cash is all over the data but it hadn’t been enough to elicit a bigger binge in the non-durable space than what had become pre-recession “normal.” Combined, total spending on goods is still a huge 9% better than January 2020 (up to February 2021; again, this number will be larger in March 2021).

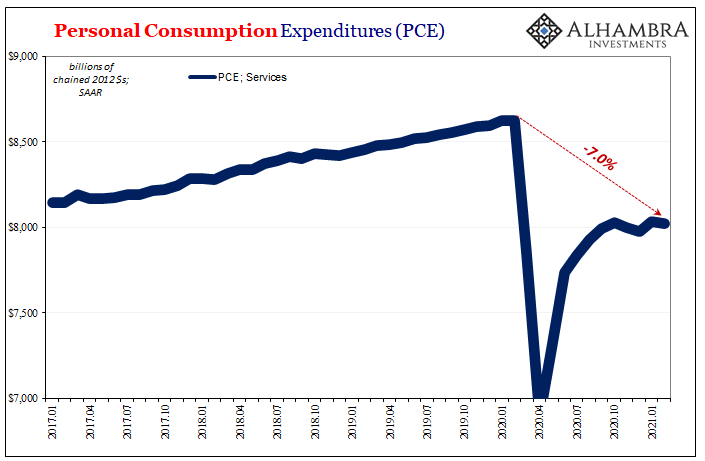

All that’s left is consumer spending on services – which is where the problems only begin. Not only is the service sector nearly twice the size (in PCE terms) of total goods, here is the epicenter where all the big economic factors have combined to hinder and destroy activity and capacity.

Restrictions plus some plain gone-out-of-business, what’s left is a decimated services industry that going back to the bottom of the last employment trough in early 2010 had been the only real area of job growth (waiters and bartenders who now find themselves on the wrong end of it). Small wonder the labor force never regained its pre-2008 numbers, Americans were never thrilled with what small gains the “recovery” primarily in this sector had been able to produce.

Whereas durable goods spending is through the roof, services outlays were an astounding 7% lower in February 2021 than the previous January (which will be a smaller negative in March).

What that reveals is another angle to the transitory twist; some segments of consumers are spending on goods what they’d otherwise have spent on services. Can’t go out, buy something online in lieu. The introduction of “free” cash from the government especially to those who haven’t been harmed by this recession has induced what amounts to an enormous distortion.

Ironically, then, as the economy continues to rebound and try to heal there’s a very good chance services spending comes back up at the expense of goods. Those opposing trends meet somewhere in the near future which leaves overall consumer spending, balance of probabilities, somewhat less than where it otherwise “should” have been had governments the calm rationality to have avoided the recession in the first place.

Durable goods are way, way up and that’s feeding supply pressures/costs in addition to sentiment (PMIs), but due to temporary or transitory distortions and interventions. As things smooth out, these diminish including spending on goods and the artificial inflation-resembling picture dimly painted by them.

Along with the basics of Uncle Sam math, very real political constraints on his checkbook, there other substantial and important reasons why first producers have been reluctant to produce as if the economy is the way it might seem from manufacturing PMI’s and specific datapoints (not just PCE durable goods but also retail sales).

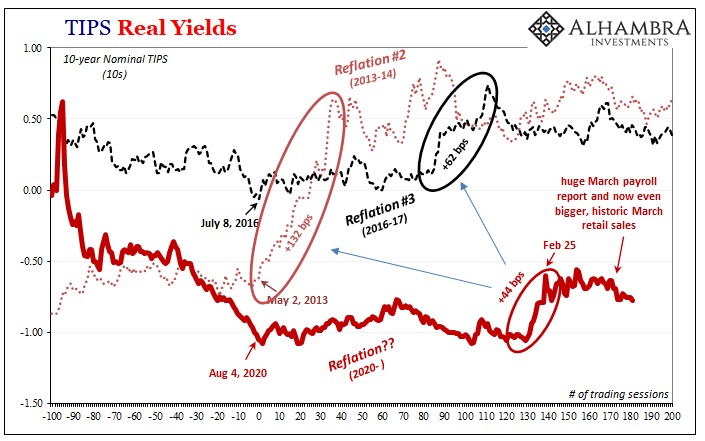

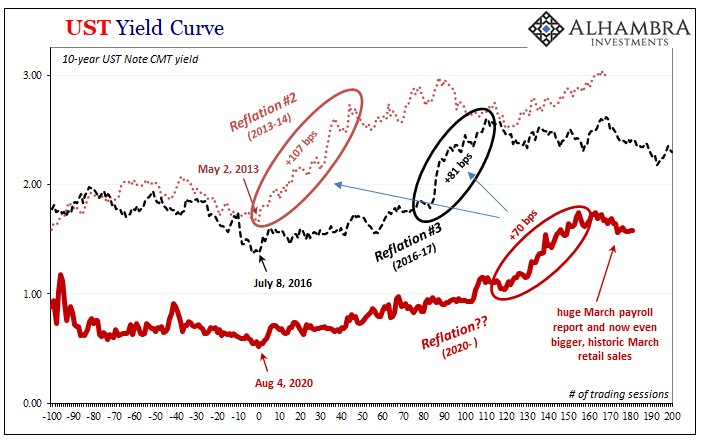

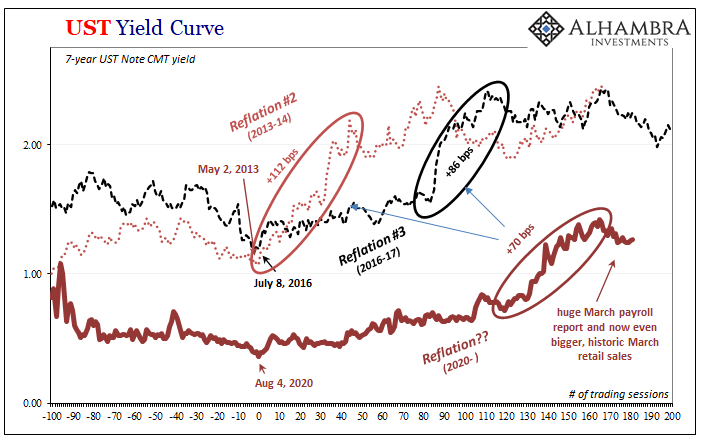

Beyond the production side, there’s also the entire global bond market where one smaller imbalance isn’t treated so dominant as it has been in the inflation narrative. This is nothing new, by the way. Where low rates and real rates have been concerned, the only thing that’s different is for once Jay Powell finds himself on the side of evidence, data, and markets (at least those not so easily swayed by the QE puppet show).

Stay In Touch