Global factors. Both for inflation as well as money, in fact money therefore inflation. Only recently, yesterday, in fact, has the Federal Reserve pulled back the official curtain of silence and illiteracy if only a little to admit there’s so much more than what you’ve ever been told. Bank reserves aren’t the end of the story, especially in light of goings-on in repo and collateral.

Both those things have global components, too, which is already outside the Fed’s jurisdiction.

So, if bank reserves don’t actually sit as the lodestar of the monetary system, effective money in it being something more and so far unknown, what else is open for (renewed) questioning? Pretty much everything that follows, from finance into economy which only begin with interest rates and inflation.

No wonder policymakers have been so reluctant to acknowledge the mountain of evidence – including much gathered on their part – against QE and its misunderstood byproduct of bank reserves. Once you pry off the lid of this particular rabbit hole, sticking your head only partway inside, you quickly surmise an incomprehensible depth inside.

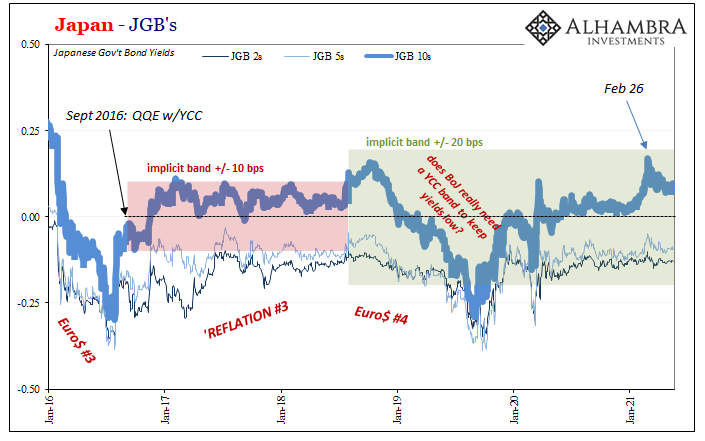

Back in 2018, Haruhiko Kuroda’s outfit, the Bank of Japan, was holding steady to his recovery/inflation gambit. On its last legs, in July that year the Japanese Governor sought to give it one final boost in the form of YCC, or yield curve control.

Invented two Septembers prior, in 2016, this alongside “overshooting” inflation targeting was supposed to raise inflation expectations via a combination of words and actions; the words being “overshooting”, as in the central bank claiming to tolerate higher and above-target inflation, whereby the actions would have been not “allowing” interest rates (bond yields) to rise prematurely thereby thwarting (in theory) the process.

All textbook stuff if being conducted using non-standard methods.

That never happened, of course. But, 2018’s last gasp, Kuroda’s Bank publicly declared how they’d let JGB’s go up more than previously; expanding the “limit” on the 10-year JGB to zero + or – 20 bps rather than the original 10. The vague idea practiced then was to signal – what monetary policy actually does – such central bank confidence that inflation and growth were so close and so near certain policymakers wouldn’t mind an extra 10 bps in yields.

Initially, JGB’s sold on the news and the 10-year rate moved above its prior “ceiling” if for a couple of months. By October, down yields went all over again only and in 2019 they didn’t stop falling at the zero lower bound. Within half a year, back at the 2016 lows.

No inflation and, relatedly, no yield curve control. More bank reserves, though.

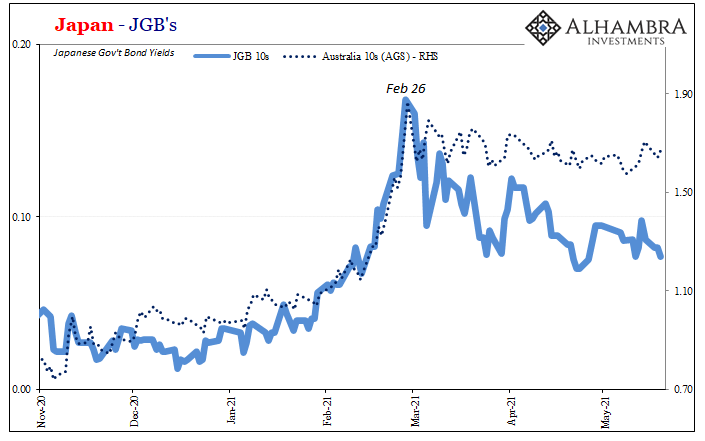

Reflation caught the JGB market again in early 2021 alongside pretty much everywhere else around the world including, for instance, Australia. There’s good reason to lump those two together given each’s proximity and trade/finance relationship with a particular other country whose five-letter name begins with “c” and ends with “a.”

In other words, when JGB reflation surrendered at practically the same moment (a day off) that Australian reflation had this made sense. Definitely not YCC, and if not global factors then certainly Asian or Asia-Oceania factors in common.

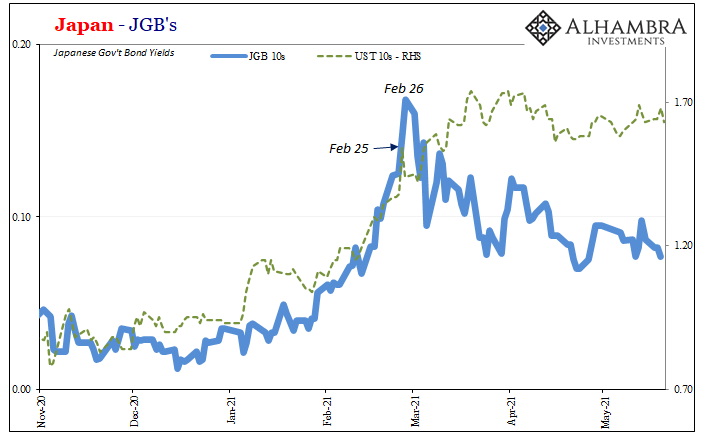

But then around the rest of the world, too, reflation-on giving up to reflation-off or at the very least this ubiquitous reflation-pause (though European markets have added a little more recently). Absolutely not YCC, possibly still China, but what else beyond? Truly global factors, after all.

Of course, as we’ve been repeatedly stressing since all this began the timing couldn’t have been more obvious at least so far as coincidence and raw correlation. Given how only the one US Treasury auction fared differently, that specific one, this provides a solid, compelling layer of evidence arriving at causation.

I’m (still) talking about Fedwire on Feb 24 (because three months later it’s still the most prominent chart point) and its immediate aftermath first in Treasury liquidity (centered on dealers) and then the pretty obvious global factors driving yields worldwide (or in enough places). None of it should’ve happened if “abundant reserves” meant anything meaningful money-wise.

Not only that, in yesterday’s sanitized FOMC minutes the Committee possessed enough sudden saneness to connect and include what’s lacking about “abundant reserves” to possible Treasury market issues very much like a few months ago:

Nearly all participants commented that a standing repo facility, by acting as a backstop, could help address pressures in the markets for U.S. Treasury securities and Treasury repo that could spill over to other funding markets and impair the implementation and transmission of monetary policy. In this regard, a number of participants noted the potential for pressures in short-term funding markets to arise from time to time, even with monetary policy operating in an ample-reserves regime. [emphasis added]

With all these things linked vitally together – even the empty suits at the FOMC can no longer deny it – from UST’s to the inert uselessness of bank reserves (my characterization, and after, say, another decade it will end up becoming the mainstream view, too) to transitory American inflation as suggested by everything else as well as all these things, I have to reiterate that the inflation case thrown around in the mainstream remains the outlier.

Not just outlier, far outlying outlier.

Why did the Bank of Japan’s YCC end up being irrelevant in 2018, and again so far in 2021? The same reason we connect Fedwire to anti-reflation in global markets and now the FOMC’s statement. Effective global money has pretty much nothing to do with what everyone has been focused on.

That’s only where the rabbit hole, like the inflation “puzzle”, begins.

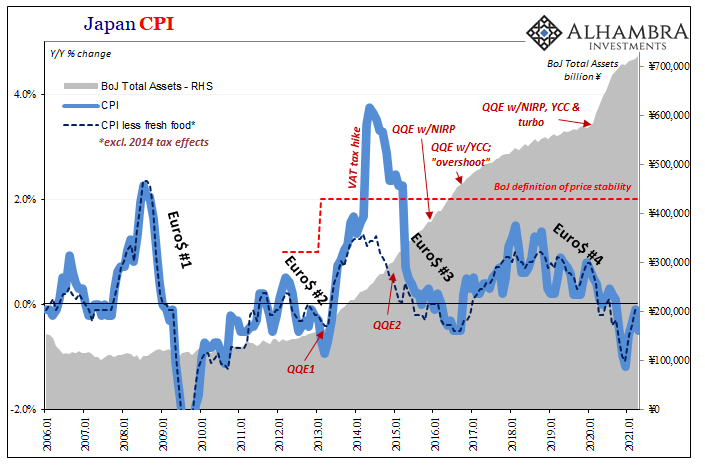

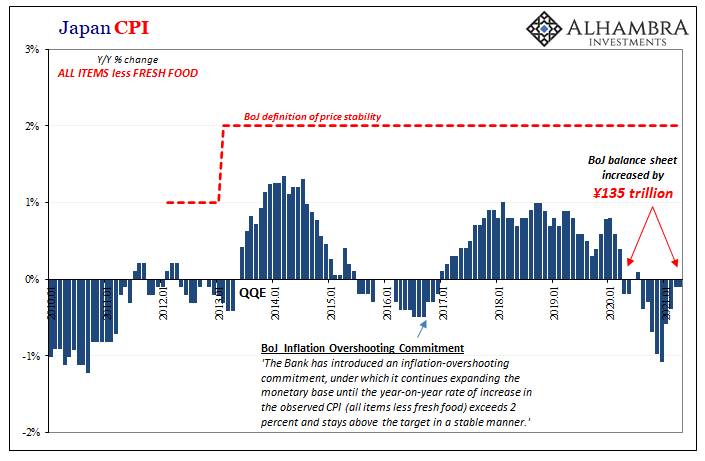

And just to drive this point home, mere minutes ago, while I was writing this, Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications released its April estimates for that nation’s CPI. Despite (yet another) radical expansion of the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet over the past thirteen months (up to the end of April), inflation once again missed (badly) to expectations while coming in even more negative (-0.5% year-over-year) than March.

The core rate, which is where the overshooting stuff applies, likewise another minus (-0.1%). Deflation here for the ninth straight month.

Is it really that much in any way probably, let alone likely, given the actual status of bank reserves, the US goes its own inflationary way or that, even more unlikely, Japan and Europe plus Australia along with the rest of the world snap out of this and suddenly shoot up to become more like the American CPI?

Or, like bond yields globally, the common factor behind them has already put the probability of continuous US inflation outperformance in its proper, transitory place. For now, anyway, this seems to be the majority, the vast majority case.

Stay In Touch