Why are Treasury bills the best of the best, the purest of the most pristine? The better part of the answer comes in the form of a mere three letters: O, T, and R. Those happen to stand for on-the-run which in repo simply means dependably liquid. OTR securities are those most recently auctioned thereby the specific securities which have under them the most robust and dependable (read: highly liquid) market.

This matters more than anything because as a repo cash lender all you care about is if you are able to sell the collateral tomorrow morning should the cash borrower – who gave you the right to seize and sell – default allowing you to exercise this last option and liquidate the asset to get back your cash.

As many repo MBS participants found out in the hot summer of 2007, having a dependable liquid market means the difference between repo being repo or facing potential serious losses (firesale) on what is otherwise supposed to be the safest funding arrangement.

T-bills are OTR; only handfuls of notes and bonds are also. Big advantage to the bills (as the world rediscovered in horror in March 2020).

There are other risks to consider, too. Price risk to the cash borrower, for one. Posting, say, a longer-term instrument whether Treasury or some other kind exposes the funding transaction when rolled over repeatedly to potential adverse price factors. For debt instruments, this means largely inflation/growth risk when the bond market greets both those things negatively by lowering prices over time.

You start out with $100 10-year UST notes valued at $99 in repo, but then reflation hits and within a short while inflation potential reprices some of that collateral right out from under you. This can and does impact both the collateral owner as well as the cash lender who might wish to alter haircuts should reflationary selling strike any market, such as bonds in January and February.

The shortest forms of debt, on the other hand, these don’t exhibit much by the way of the same non-liquidity price factor risks like inflation. Treasury bills, in other words, again are in higher demand overall as their limited maturities (and near-constant OTR source, refreshing features like the discounting rate) likewise limit this risk. They are inherently price-steady.

Double advantage bills.

But what if there aren’t enough bills?

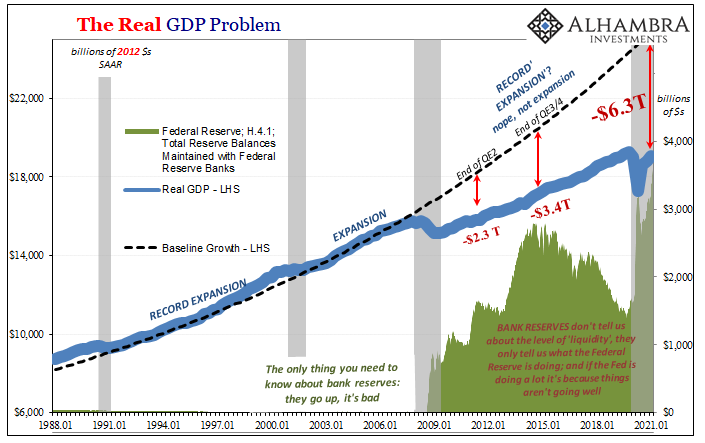

If that’s the case, we wouldn’t know it via any direct assessment or data. Even though repo and collateral (as well as collateral for derivatives) have been front and center in every major acknowledged and unacknowledged monetary shortage since Summer 2007, these have yet to make much way into official and mainstream assessments which continue monolithic focus on bank reserves.

As we pointed out just recently, the FOMC only a few weeks ago issued a partial, half-hearted confession about how Treasury repo can make waves in the monetary realm no matter the level of bank reserves. Nearly fourteen years later, the central bank world has only now begun to ponder these implications more seriously – and once they do so more completely, it will rock monetary policies to their very core (accounting for so much time wasted to try to explain reality, their inflation “puzzle”, for one, any other way).

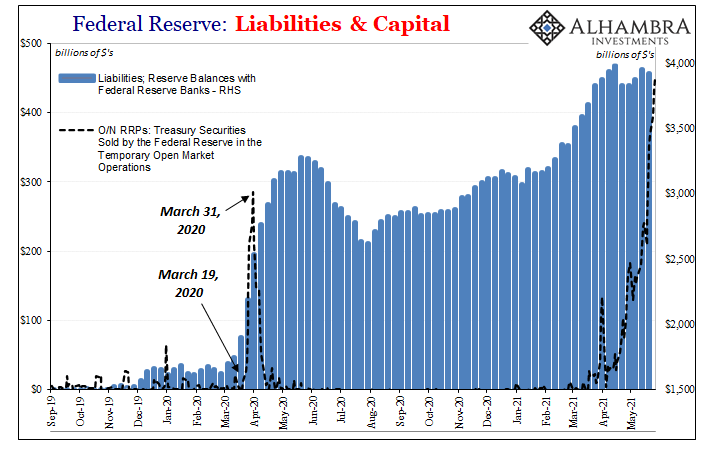

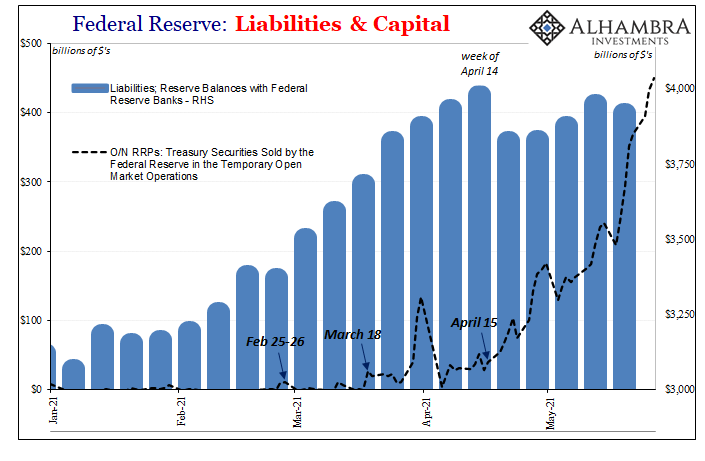

This the state of affairs, there is again no way to directly determine the systemic collateral condition. Yesterday, we examined this possibility from perhaps an unusual angle – the Fed’s reverse repo facility (RRP). Today, the window saw another bump higher in usage, bringing the afternoon total to more than $450 billion.

To those who remain fixed to the Fed-centric monetary model where bank reserves are worshipped supreme, that has to be what all this reverse repo fuss has been about. Big increase in reserves, meaning allegedly spare money, therefore seeking an outlet for this “flood” money market participants turn to the RRP as one alternative as it was designed.

Too much money (an allegation made, not randomly, often by the very same people who for years have been claiming too many Treasuries).

Why the level of bank reserves reached in the middle of April happened to trigger the almost parabolic rise in RRP demand isn’t discernable – because it doesn’t actually make much sense.

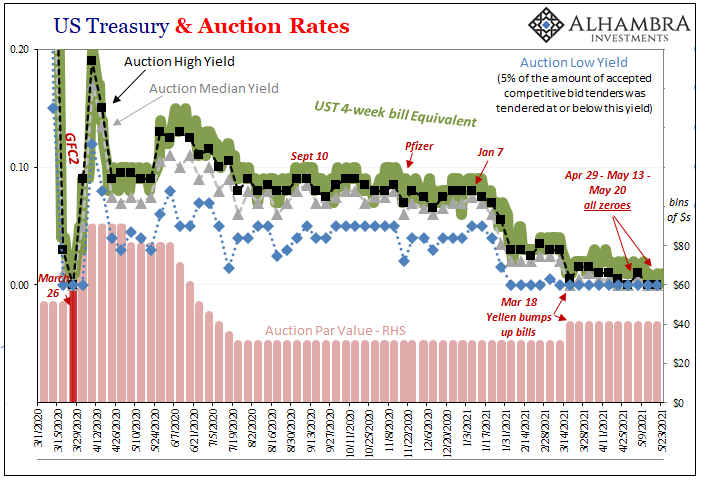

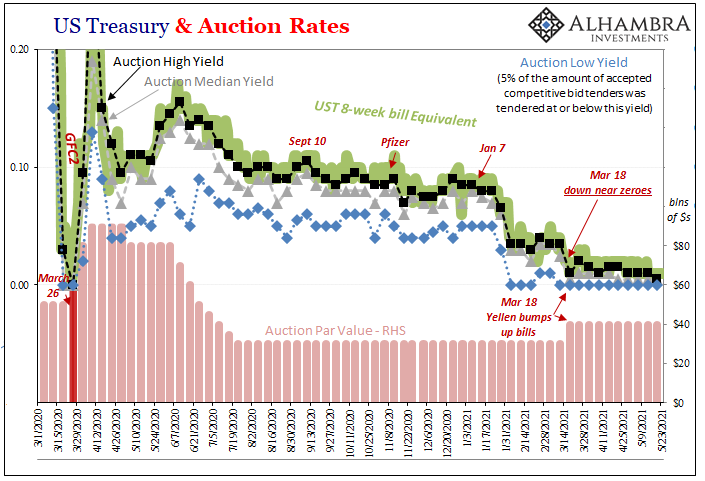

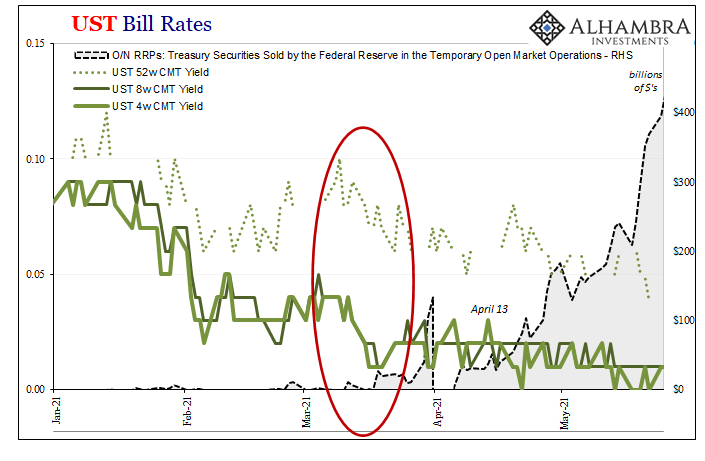

In fact, as we pointed out yesterday, the more obvious trend in reverse repo began beforehand back in the middle of March which instead was consistent with a noticeably sharp drop in bill yields even as Janet Yellen’s Treasury Department tried to supply more of the major issues.

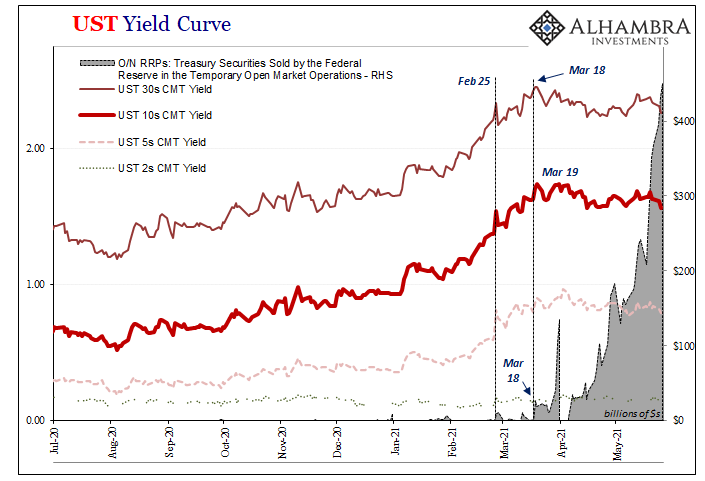

While that was where we left off, it only gets more interesting. The first, more serious bump in RRP usage, that second one on the chart above, just so happens to have occurred on, hold on to your hat, February 25 and 26. Yes, those particular days again (I’ve made sure to mark it on the chart below).

Three months after Fedwire, what should have been a minor footnote instead remains as a significant point or inflection in not just UST yields and indications more importantly for those across the entire world’s bond market. From Japan to Australia, New Zealand into metals and crude, this was a very small issue having been turned into something, now something more serious that has lasted a quarter of a year.

Reflation pause which, in a sense, is anti-reflation given just how much has purportedly been going the right way (for the recovery case) since around the start of 2021.

Yet, it had been nominal Treasury yields, for one, which sort of defied that global anti-reflation turn. Over the next few weeks following Feb 25’s major selloff on into mid-March, while TIPS real yields took the same direction as JGB’s and the like, nominal UST’s continued upward (yields) holding to the reflationary trajectory.

But only until mid-March which just so happens (another “fluke”) to coincide with both that sharp drop in bill yields along with the beginning of this more serious RRP fascination. The chances of this being some random accident is, like T-bill yields, just about zero.

Not only that, to our point, how does “too much money” get translated by long-term and inflation-sensitive Treasuries into anti-reflation? It had been, quite contrarily, this “money printing” flood story which had been responsible for much if not most of the inflation hysteria thus far.

No sir, this is collateral contributing even more to the deflationary pressures already visible since Feb 24-26. If we view the RRP – explained yesterday – as a possible, even decent indication of collateral constraint or scarcity, then what you see above actually makes perfect sense. Reflation is and has been real, but like all those (three) which came before this latest one it already is being undercut by deflationary, anti-growth monetary deficiencies only starting in the world’s collateral streams.

Bill prices fell (again) sharply mid-March, meaning higher than usual collateral demand. This appears to have led cash-rich non-banks like MMF’s to scale up at the Fed’s RRP unable to find collateral-rich cash borrowers. Because of this condition, not only are bills in high demand eventually LT UST’s are sought out and bid up as a slightly lesser replacement for sky-high bills.

The RRP isn’t directly related to LT UST yields, one causing the other, rather both are reactions to almost certainly the same thing. Highly complementary results, even more compelling as they are taken/derived from very different parts of this same system.

The global money system has a reflation problem, but it’s actually the one the FOMC backed into almost inadvertently in its last published statement (minutes). This was the very piece of text that practically the entire world ignored and didn’t realize was the only thing worthwhile in it. I’ll repeat it here for good measure:

Nearly all participants commented that a standing repo facility, by acting as a backstop, could help address pressures in the markets for U.S. Treasury securities and Treasury repo that could spill over to other funding markets and impair the implementation and transmission of monetary policy. In this regard, a number of participants noted the potential for pressures in short-term funding markets to arise from time to time, even with monetary policy operating in an ample-reserves regime. [emphasis added]

While this is somewhat like news to policymakers and would be a shocking development to the mainstream textbook view, it is neither of those to market participants who have been aware of, as well as prone to, collateral problems going all the way back these nearly fourteen years regardless as to whether the Fed acknowledges them or not (up to now, not).

And in that soon-to-be decade and a half, all we’ve ever heard was abundant reserves, too much money, and too many Treasuries. All these things at first sound incredibly complicated and dense, and maybe they are, but putting these pieces together and understanding how they fit – with each other as well as with the rest of the world’s continuously “unexpected” negative developments – actually isn’t all that difficult once you ditch the conventional Fed-centered worldview.

Stay In Touch