China’s Cultural Revolution itself was, after all, an attempt to reconcile against factions threatening from within the ailing country’s rudderless position of that time. Red Guards were formed especially from young students who were as equally zealous ideologues as well as frightened being exposed and left on the wrong side of unfolding history.

It’s always students in these Communist “peasant” uprisings and backlashes.

Mao Zedong had practically ruined the country during its utterly disastrous and chaotic Great Leap Forward genocide. So utterly stupid and destructive, its aftermath threatened to immediately undermine the entire socialist project. If Mao’s gang contained China’s highest hopes for a scientifically-determined utopian future like they said, but which led to the starvation (and political repression) deaths of tens upon tens of millions, maybe these people didn’t have a clue what they were really doing.

The Cultural Revolution which followed was the backlash against the backlash; one which re-established Mao on top and his way of thinking as perhaps inevitable. It was easy enough to blame the Russians and the Leninist mistakes of having imported and overlayed Soviet culture onto a Chinese set of circumstances.

Still, answers would have to be given for that turbulent period. They wouldn’t really be offered until 1980 and 1981, long after Mao’s death and with Deng Xiaoping nestled more comfortably as his successor. Deng wanted the Party to come up with some way of admitting Mao screwed up without it undermining the whole system.

In June 1981, at the Sixth Plenary Session of the Party’s Eleventh Central Committee, Deng issued his thoughts on this historical reconciliation process.

Mao Zedong Thought was set as the guiding thought for our whole Party at its Seventh National Congress. The Party educated an entire generation in Mao Zedong Thought, and that is what enabled us to win the revolutionary war and found the People’s Republic of China. The “Cultural Revolution” was really a gross error. However, our Party was able to smash the counter-revolutionary cliques of Lin Biao and the Gang of Four and put an end to the “Cultural Revolution” and it has continued to advance ever since. Who achieved all this? Is it not the generation educated in Mao Zedong Thought?

But, Deng admitted, Mao made a lot of mistakes, a lot, including some really big ones. The challenge was to diminish them enough without too much blatant whitewashing so that in the end Mao Zedong Thought could be essentially purified as more than some anodyne historical retelling. It was still very convenient to a country still very much caught up in the cult of Mao.

This time, as we intend to give a correct evaluation of Mao Zedong Thought and scientifically establish its guiding role, we have to expound its main contents in general terms, especially those elements which we shall continue to implement in the future. Comrade Mao Zedong made mistakes during the decade of the “cultural revolution” [1966-76]. In our appraisal of him and of Mao Zedong Thought, we must analyse those mistakes in the spirit of seeking truth from facts.

For what Deng wanted to achieve, modernizing an economy that had been put backward for more than twenty years by this Maoist claptrap, it required a coherent and homogenized popular spirit. That much Mao did right, the politically useful outgrowth of the Cultural Revolution.

So, Deng would clean up the economics, so to speak, while leaving the enthusiasm of Maoism steeped in Sino culture in place if stripped of its most extreme format – the cult of Mao.

This worked for much of the last forty years because the economics hadn’t just succeeded – meaning China’s clear-cut embrace of a limited capitalism and free markets. This wasn’t some admission Communism was all wrong; on the contrary, the Communists deep-down know they don’t create wealth and it’s not really their purpose. In fact, Mao’s Great Leap Forward was another abject lesson in the dangers of Communists trying to do something they can’t do.

That paradigm of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics had lasted for decades if only until around 2011 or so. By then, it became more ruthlessly clear to especially Xi Jinping something would have to change. That period of Chinese growth was really one of global prosperity fed by a system increasingly unlikely to survive the 2008 crisis (it didn’t).

What to do in its absence?

Less global, more China (rebalancing). But if that doesn’t work in economics, and it hasn’t, then more China meaning culture, too. In many respects, Xi has purposefully gone back to Mao – even if Xi’s own father and half-sister had been political victims of the Red Guard during the Cultural Revolution. Whatever the economic chaos of the time, the Party stood unchallenged because of its ruthless herd thinning.

Over the past year, Xi’s Communist regime has upped its propaganda aimed at students and those even younger. “Passing on red genes”, the nation has been told (and issued guidelines) to adhere even more closely to Xi Jinping Thought. Communist Party youth organizations are making regular weekly efforts to combat any even the slightest hints of “historical nihilism.”

This phrase has been key to Xi’s tightening grip. Less economy, more crackdowns. “Historical nihilism” is the current catch-all to any deviation from the official Party history.

Wang Binglin lectured his audience on controversial subjects, such as the party’s iron grip on history ever since Mao Zedong seized power 72 years ago. In particular, he warned the scholars in attendance to be careful when speaking and writing about the party’s violent land redistribution campaign in the early 1950s that claimed the lives of as many as 2m people.

“Playing up [the attack on landlords] is historical nihilism,” Wang said, referring to the term used by President Xi Jinping to criticise anyone who deviates from the party’s official historical narrative.

Instead, the Party has focused on…schlock. The government has choreographed flash mobs, groups mostly students who sing and profess their love for Xi and his Communist government. There have been rap songs (seriously), new films (a ton of them) and even a new history museum – Communist Party history museum.

Flash mobs are breaking out across China as citizens sing the praises of the Communist Party in the run-up to the centennial of its founding. "I will always listen to the Party and follow its guidance." https://t.co/4I04ntVYbR

— Jonathan Cheng (@JChengWSJ) June 22, 2021

Behind it all, China’s already-ubiquitous social credit system that gains more intrusiveness by the day. Love your Xi because he loves you back whether you like it or not!

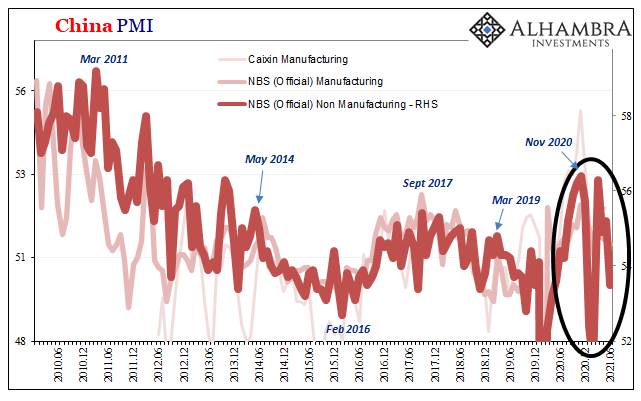

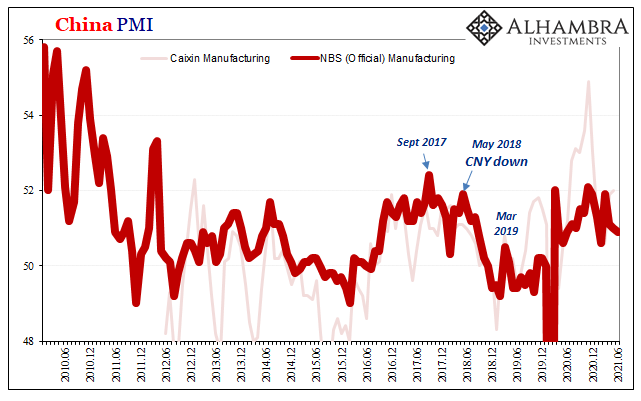

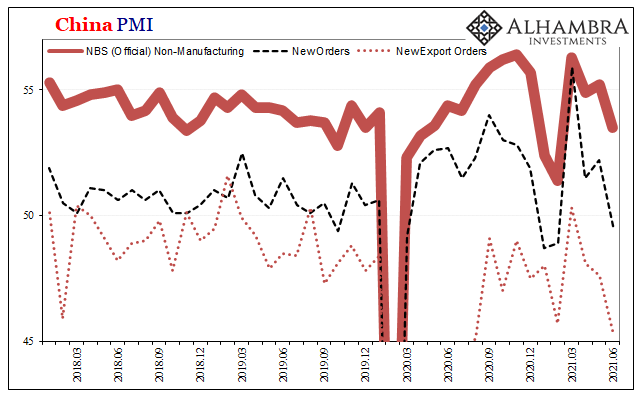

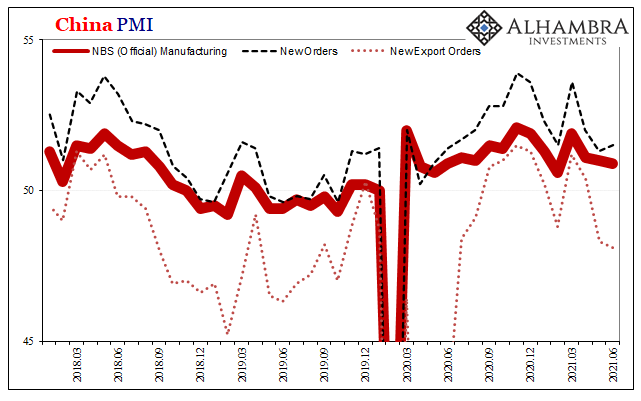

One thing’s for certain as China’s Communist Party reaches the end of its first century (it actually did back a week ago, but an ancient mistake has kept July 1 as the official date anyway), there’s even less economic growth on the horizon (see: below). The Chinese economy continues to struggle even if the songs, the flash mobs, and ghosts of Mao make it seem like China is a giant monolith of health and contentment.

Maybe that’s the whole point.

The emphasis on the red gene is as history, too. Coming full circle, the economy of Deng is long gone and fading. What’s left is Xi looking like Mao because that’s what China really does, and nowadays it has much less economics to do otherwise. Not good:

Stay In Touch