A lot of American workers still quit their jobs in May, just fewer than the huge burst who had during April. We don’t know why, of course, and the BLS JOLTS data isn’t going to tell us. Nor will it say anything about why companies aren’t hiring at a much more rapid frequency.

Some say it is a labor shortage, generous government benefits that pay better than work. A school system that remains shuttered in many places or at best in “hybrid” mode requiring parents to refrain from working. COVID fears. Etc. Companies are in huge demand for labor, they can’t find near enough.

On the other hand, maybe companies just can’t pay – either the wage rate which would pull potential laborers back into the employment market, or pay anything at all for any workers because business has been harmed and contrary to conventional assessments of a booming economy the harm hasn’t really been assuaged nearly enough by Uncle Sam’s various forms of check writing.

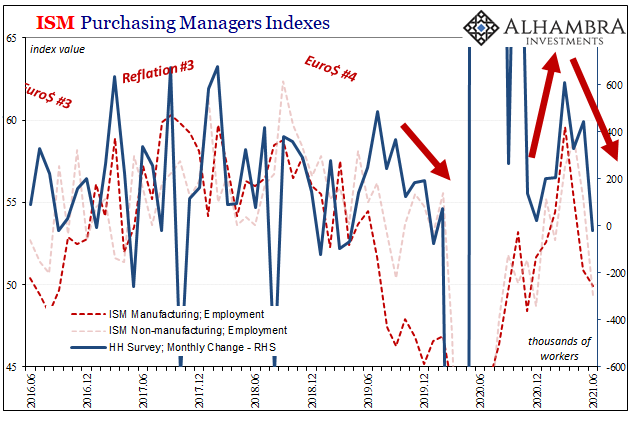

Two very different viewpoints: one leading to runaway inflation, or perhaps just a realistic possibility for this; the other the same dichotomy in all the same places as we’ve seen this twice before and neither proved to be in any way inflationary.

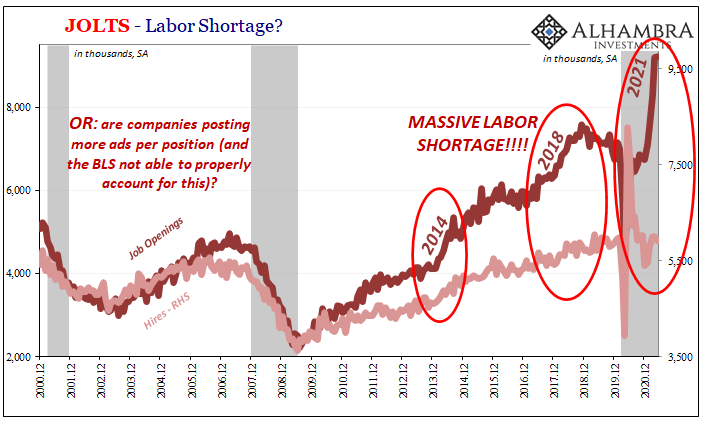

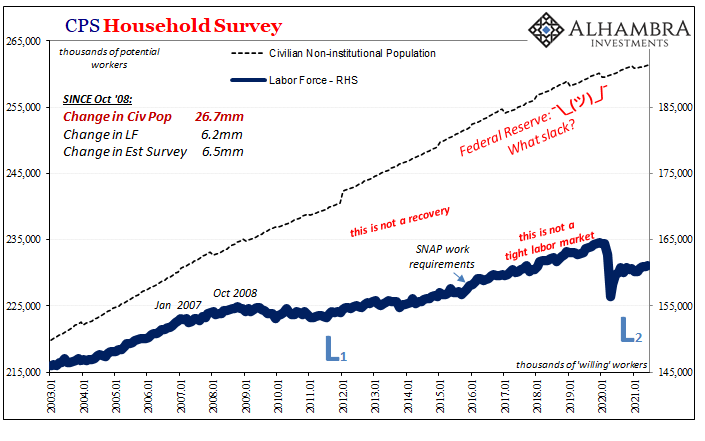

JOLTS has been Ground Zero for this debate ever since the data on Job Openings surged right from the get-go of 2014. But as purported demand for labor skyrocketed, the actual procurement of workers did not. The economic pace of hiring increased, along with the major labor data like the Establishment Survey, but each was blown way out of proportion (oftentimes purposefully) even if the moniker “best jobs market in decades” was technically true (economically meaningless).

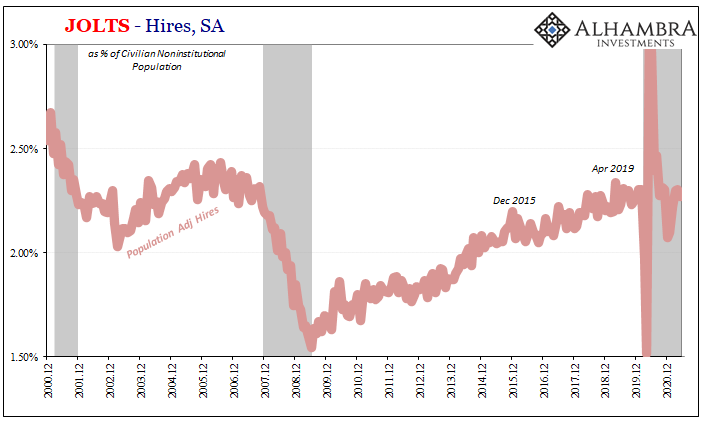

This problem – never once answered – only grew worse during 2018’s Inflation Hysteria #1. Again, Job Openings went in one direction while the rate of hiring failed to follow; only modest increase though stuck at a level still significantly below the precrisis period, which wasn’t exactly robust itself.

Since inflation was the projection from the Federal Reserve models on down, HI was ignored while JO was interpreted and accepted widely as definitive outside of markets as having correctly outlined the situation.

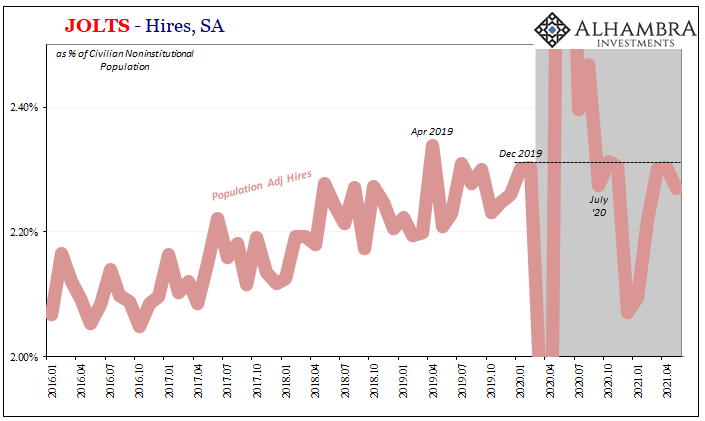

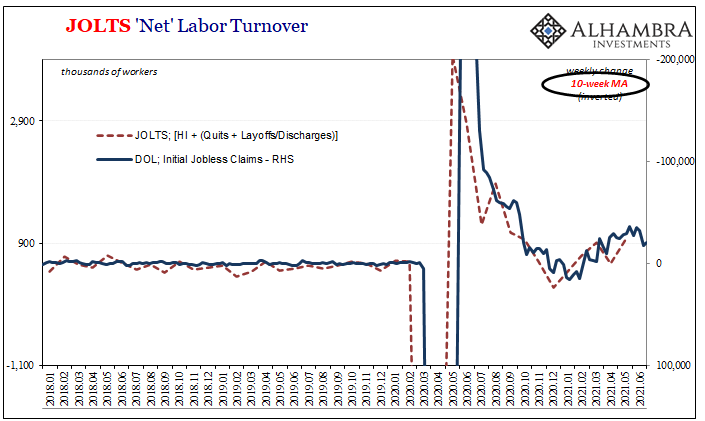

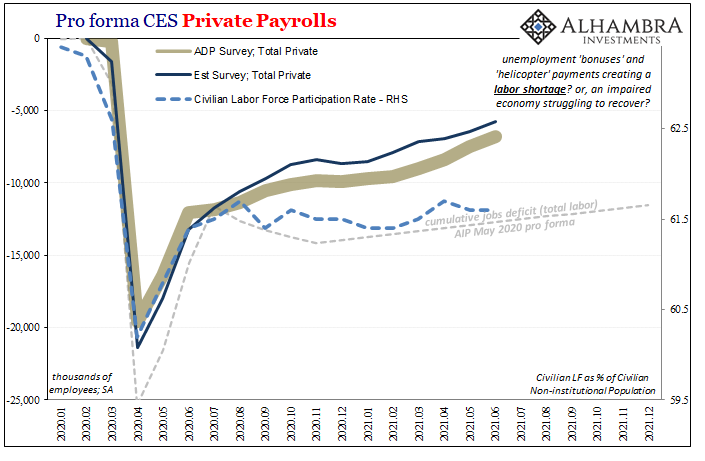

Here we are all over again only with the distance between purported demand for labor (JO) even greater than at any time in the data history. Yet, despite the massive layoffs and subsequent incredible creation of slack last year, the rate of hiring is barely equal to late 2019 levels; hardly the sort of desperation you’d associate with the inflationary fires of conventional thinking.

Prevented from hiring, yes, but by what? Lack of willing workers, or lack of economy?

In 2014 as again in 2018, bonds were decisive. Nominal yields had been falling all throughout that “best jobs market in decades” which proved to be the correct position on US inflation (which is actually determined by a synchronized global economy tied tightly together by a singular monetary system already by then moving steadily in the wrong direction; never “decoupling”). Once the dollar joined the dysfunction (eurodollar shortage) it was as clear a signal of which economy was actually happening as you’ll ever get.

Economists remained confused despite such clarity worldwide.

So much so, they missed the same signals in 2018; preferring the JO figures (as well as the unemployment rate), a LABOR SHORTAGE!!!! was fashioned to reverse engineer a predetermined conclusion (Jay Powell said it was inflation!) First flattening and then inverting, yield and money curves (esp. eurodollar futures) didn’t just express skepticism about the labor shortage possibilities and therefore inflation, they downright traded against them.

You know where I’m going with all this; in this third instance of JO vs. HI, now with JO pushed ever farther into the stratosphere and giving hope to this next LABOR SHORTAGE!!!! and its even stronger Inflation Hysteria #2, bonds aren’t just trading (right now) on skepticism they are (worldwide) once more betting directly against it.

Falling yields (though not yet complete rising dollar) are squarely on the side of a negative, pessimistic HI, interpreting this (along with an actual wealth of other global data) as sourced from more-than-temporary economic harm revealing itself as the tide of artificial fiscal influence predictably recedes.

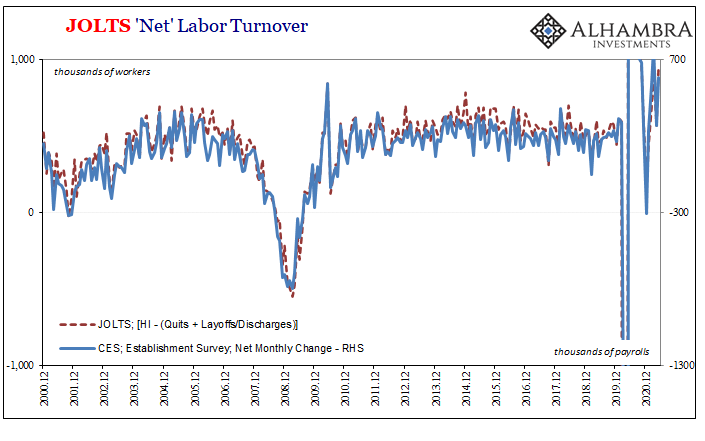

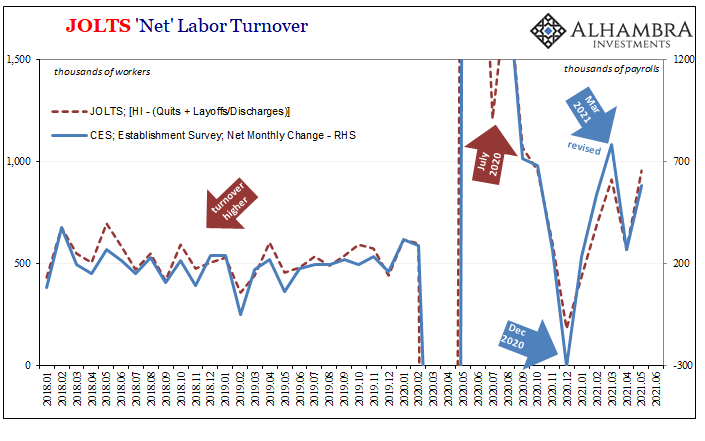

As to the housekeeping aspects of JOLTS, the numbers are almost exact to the Establishment Survey (through May 2021; JOLTS is one month further in arrears than the CES). There had been ~90,000 fewer layoffs/discharges during May when compared to the disappointing payroll month of April, but also nearly 400,000 fewer voluntary quits.

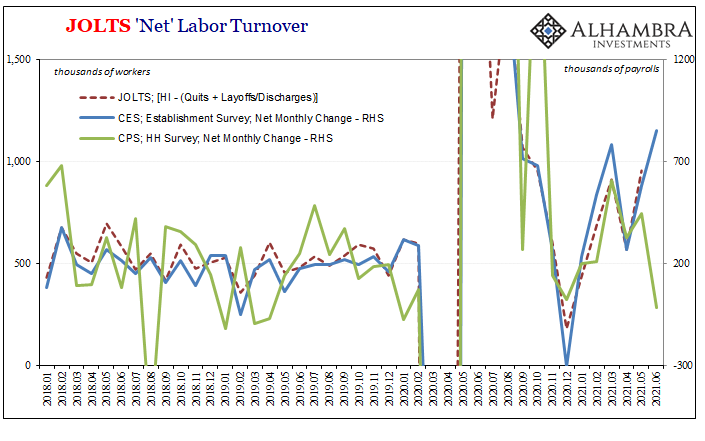

It had been the latter which, according to JOLTS, had spoiled the headline April Establishment Survey (again, for reasons not known). Together with about 100,000 fewer hires, the net turnover increased from 570,000 previous to 955,000 for May. This was pretty much right on the (revised) dot to the Establishment Survey (583,000, accounting for the statistical factor between JOLTS turnover and CES payrolls).

Of course, this only raises more questions creating, as it does, still another potential labor data discrepancy; in this case between JOLTS turnover, the CES Establishment Survey and now the CPS Household Survey. As mentioned yesterday (and last week), the last has dropped considerably over the past few months which corresponds quite closely with outside labor market data (the two ISM’s, in this case).

The burden of proof, so to speak, was already on the inflation case after two previous (and still unexplained) failed predictions, the last one specifically described as the same exact type of labor shortage (demand for labor through the roof, hiring lackluster because Economists need to believe Americans are just lazy). For inflationary labor to be even possible, this would require at the very least unambiguous signals across a wide variety of just jobs market data let alone economic data in general.

Instead, here we are again with more than inconsistencies to the point of outright contradictions. Is it more likely American companies are so desperate for workers only to be unable to find them even as millions upon millions (labor force) self-report to the BLS they aren’t bothering looking for work? Or, balance of probabilities, is it a higher probability that some companies might be looking for workers but aren’t able to pay the market-clearing wage while far too many other businesses can’t even pay a single penny because, yes, the gigantic 2020 recession (and lasting effects of GFC2) had caused, in fact, enormous, not-easily-fixable economic destruction?

The BLS data won’t be able to tell you, giving you, as it does, evidence for either answer. Again. And the very idea of long run problems have been dismissed if only to make the inflation story seem plausible even as the world’s experience with 2008 and its aftermath proved the concept (and then some).

This is the one big reason why we look to the bond market (across all its facets) because unlike stocks those operating in it are closely associated with what’s really going on in the real economy in real time. Its verdict is, for a third time, loud and clear. Inflation, and the recovery/economy which would foster it, remain an extremely slim prospect.

Unless something meaningful changes soon, which obviously does not count “infrastructure”, those recovery prospects are perceived as less by the day with each new data point. Including Job Openings.

Stay In Touch