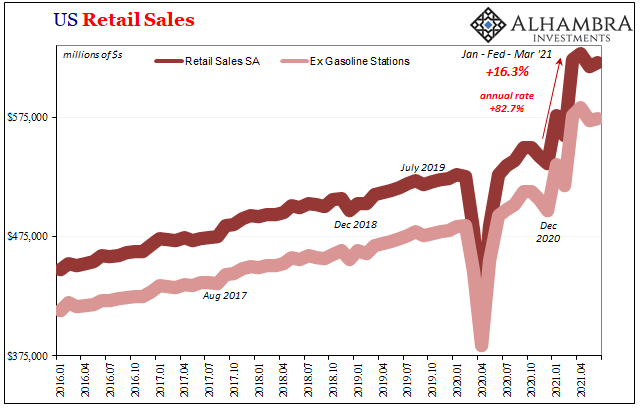

Count retail sales (US) among the dead data. Like recent CPI’s and PPI’s, consumer spending on goods continues to be sky high – and yet markets (even stocks) don’t seem to care. For the month of June 2021, the Census Bureau believes total sales were up when compared to May, though not much as May’s estimate was revised lower.

At $621 billion during last month, this was 0.55% more than the prior one but significantly lower than April (and less than January). While Americans keep splurging, the nagging sense of the splurge being tied mostly to the federal government’s influence wasn’t reduced by this monthly retail sales report.

And then there’s services – a completely separate data series and even more nagging issue.

If the retails sales binge has indeed seen its best days, and those best days didn’t quite offset the ongoing dearth of services spending, the seemingly one bright spot for the entire global economy finds this light rather dimmed by future implication.

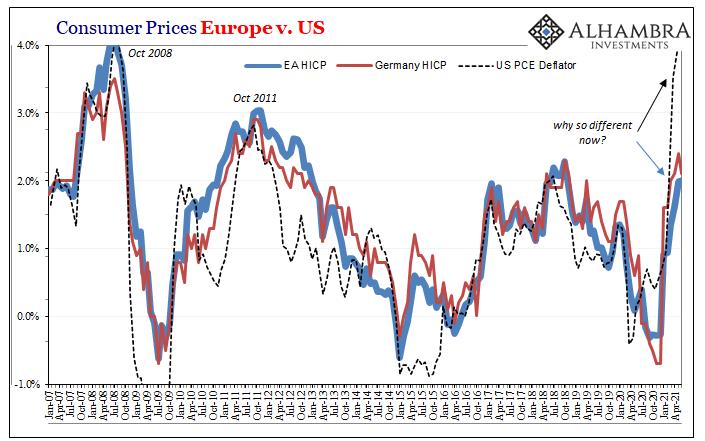

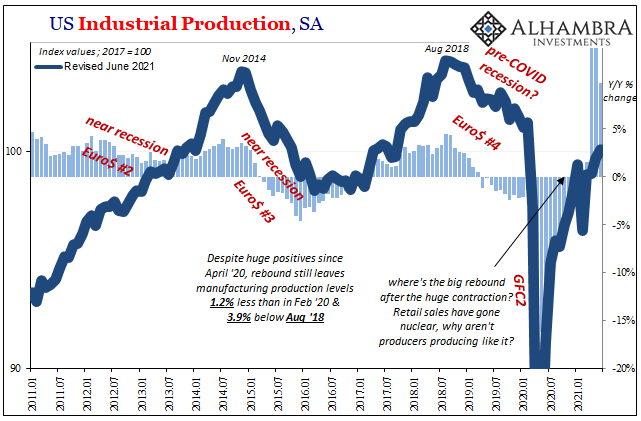

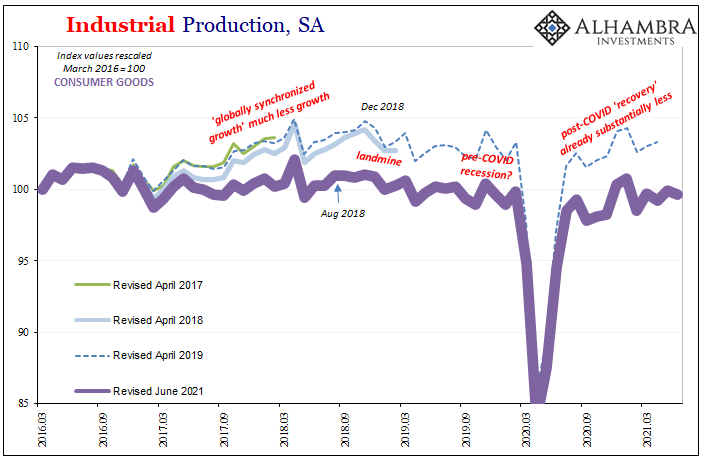

However, what’s pretty clear is the “inflation” ongoing at the same time. As we’ve been chronicling all along, the difference between sales and production certainly explains much probably most of the rise in prices. Demand for goods up in the stratosphere while production of goods (and more) remains severely depressed.

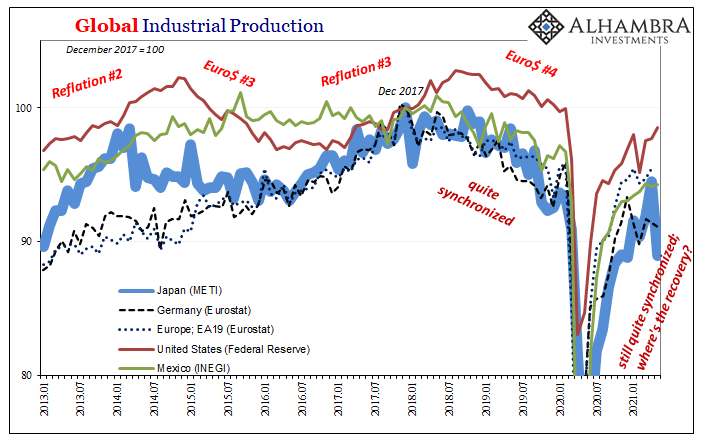

Prices have adjusted to this imbalance. The oppressive presence of the US federal government, therefore, in the economic behavior of consumers, especially, explains the huge difference between American inflation estimates and those around the rest of the world which are nowhere near as high. And this is all the more important given that industrial production is quite uniform in all these same countries – including the US.

What everyone really wants to know is in which direction will this all converge? To answer that question, you have to begin by figuring out first why production hasn’t rebounded much at all. Most people seem to believe, and what you’re told uniformly in the financial media, is supply bottlenecks and input shortages.

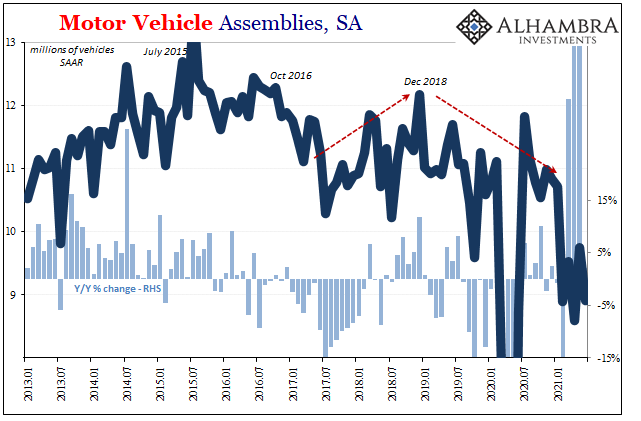

Producers would produce more, supposedly, if they had more component parts available to put into their final products (this problem most starkly restrictive in the auto sector). Yet, in other industries that cannot be the case even as output near across-the-board is very much like it is for vehicle production.

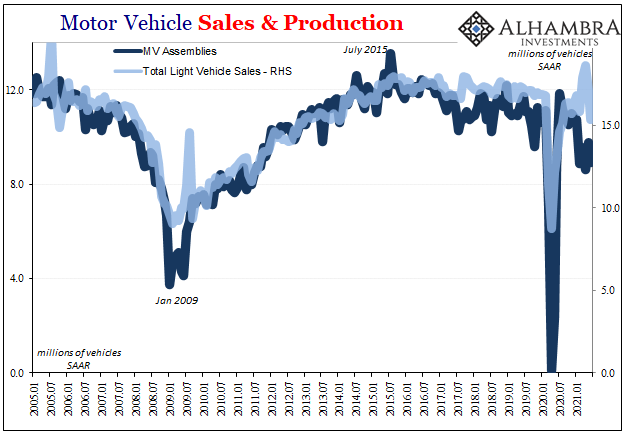

There absolutely are supply problems in exceedingly low automobile manufacturing output (motor vehicle assemblies, for the IP data), but that isn’t the whole story. The same debate has been revisited again on the sales side after (according to BEA estimates, in contrast to Census and retail sales) total auto sales slid sharply in June following just two months of Uncle Sam-fueled mania.

Was it because of this lack of inventory supply bottlenecks have forced into the wholesale and retail channels? Again, most say, yes.

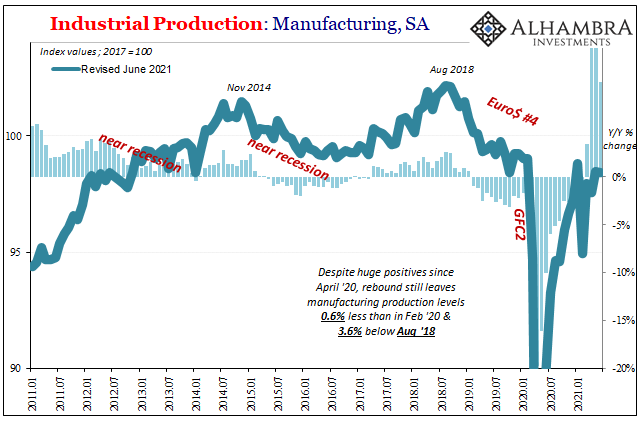

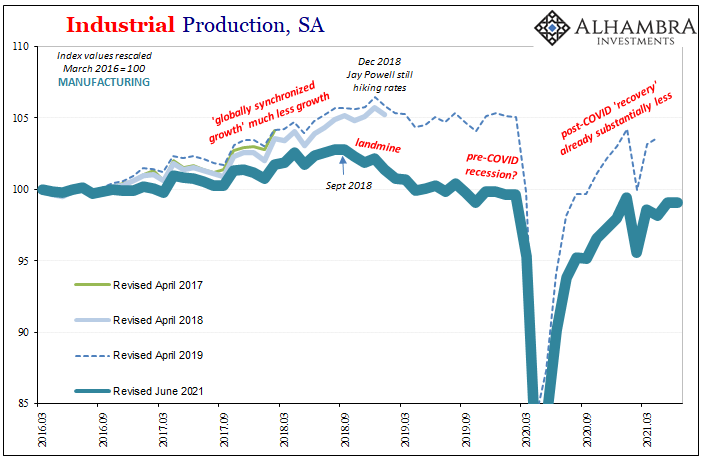

The entire manufacturing sector, though? The full space of American industry? No. According to the Federal Reserve’s latest estimates through June 2021 (released yesterday), total manufacturing output – despite the retail sales numbers you see above – was still 0.6% less than it had been in February 2020. Even more eye-opening, a small decline in last month’s output (compared to May) put the same as 3.6% below August 2018.

The entire sector hasn’t yet recovered the COVID recession let alone the pre-COVID recession-like downturn which preceded it. This can’t all be due to supply problems and/or a(nother) presumed labor shortage. There is willfulness in these figures which are found similar all throughout.

Instead, producers are willing to sit mostly idle even as consumer (and producer) prices have jumped over the past few months. Unable, or unwilling?

If the former, supply issues, then production will surge at some point this year. It would have to considering half of it has already gone by. In this case, consumer price acceleration turns around once supply begins to catch up to demand (the potential for which has caught up to a bunch of commodities).

If the latter, then this would only be the case if producers are expecting the goods economy splurge to run its course; for retail sales to head back lower as the transitory impact of the government’s influence wanes (even as that same government is now paying monthly “child” stipends).

In other words, demand falls to converge with low supply. Inflation, therefore, also not inflation.

There is a third possible option being thrown around which takes supply bottlenecks to an even greater extreme by first coopting the macro idea of “sticky prices”, adding to it the expectation supply will stay low, demand high (if not higher) driving inflation more bonkers for quite some time. Even retail sales aren’t in that picture.

For the inflation case, well, that’s really the only case. In either of the other possibilities, supply catches up to demand, or demand falls back toward supply, consumer and producer price pressures would eventually turn out to have been temporary; transitory.

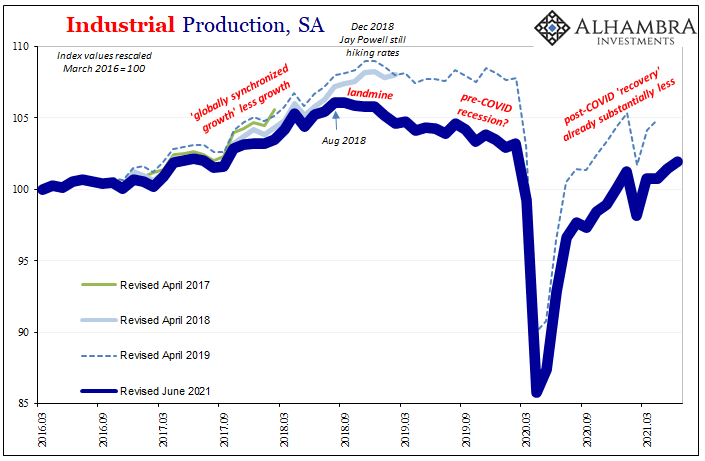

The key, it would seem, is the state of demand. High now (again, in only goods), but then what? And we also have to keep in mind that, quite possibly, production output could be even less than what’s figured right now (the benchmark revision fallacy).

Mainstream views are reluctant if not totally resistant to considering the very real possibility that demand will not make it. It is being accepted as a foregone conclusion even the spending upon goods can only stay at these extremes, even going past them.

Taking out the chip shortage and whatnot from supply, that leaves the very real (and consistent) possibility producers are producing like they expect the opposite. This rather than the other is consistent with history and current indications.

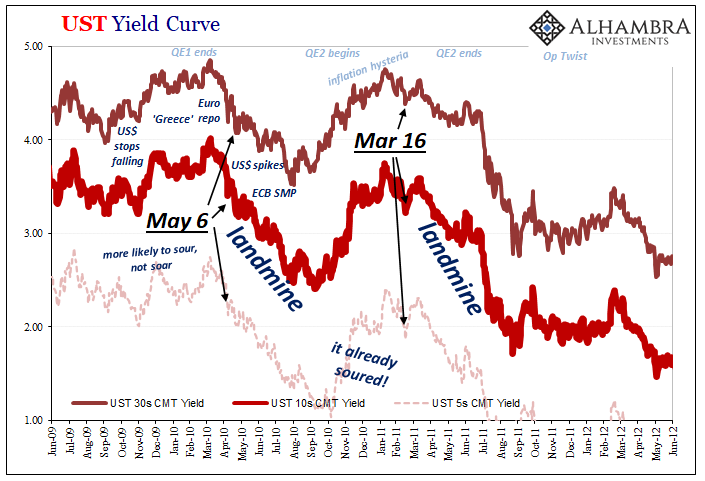

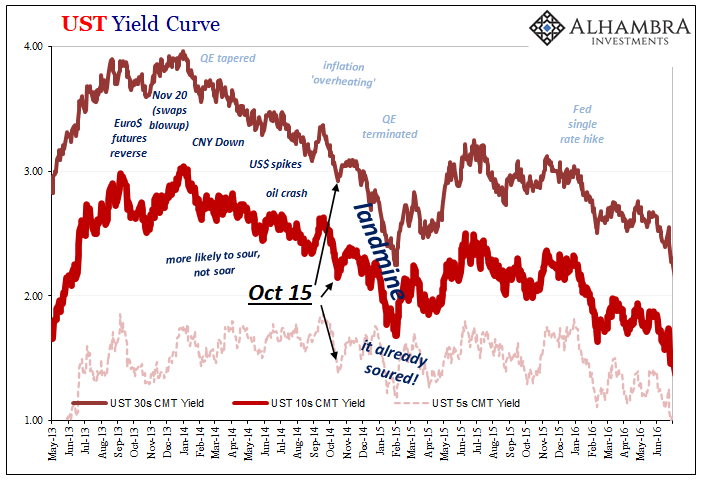

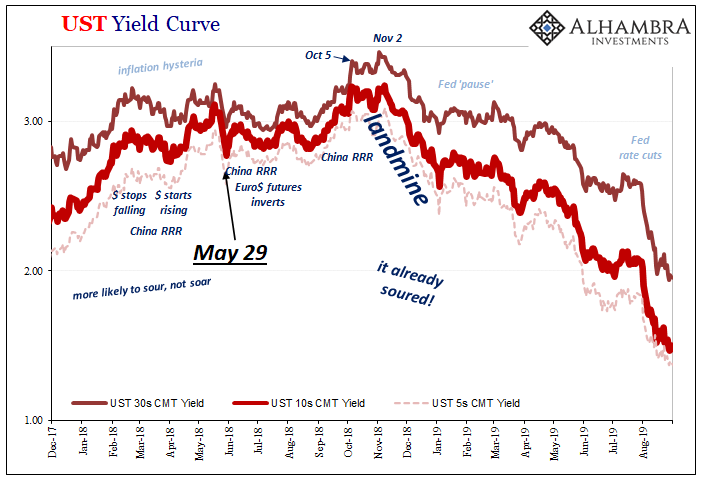

There is the real and very much growing probability of money/financial/global economy problems threatening to upset pretty much everything going. As we’ve been forced to witness – via incompetence – four times already, three recovery-like global “booms” everyone at the time is certain will only get better, each instead interrupted and quite easily overpowered by factors no one in the mainstream has yet explained.

We don’t need them to, of course, we’ve got all the warning signs and their repeating pattern. It may not have made the top of Bloomberg’s internet feed, but you can absolutely bet that manufacturing and industrial businesses have paid far closer attention to these ins and outs; maybe even preparing for this potential by not rapidly buying the inflation/recovery story much at all (a factor in those revisions; statisticians were much more positive than producers had even been during those times).

Not just US Treasuries, but global yields that have been sinking and sending off that same sinking feeling which in the past has every time correctly predicted demand sinking. At least failing to live up to the hype.

LOL

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) July 16, 2021

(Spoiler: deflationary money; collateral; we've done this four times already)https://t.co/p6AgaFreVR pic.twitter.com/L7kKqehrPq

The short version is simply this: retail sales and the CPI are dead data because they are only a small part, and clear outliers, given the vastly more relevant global whole. And unlike the past few months when it seemed like retail sales and US inflation data were the only things moving, there just may be a whole lot of hidden movement in the wrong direction as I type.

Stay In Touch