Conventional wisdom has said for a long time that a recession is two consecutive quarters of declining output. Where this idea came from, who knows. It’s a shorthand that was put together over time derived from the folks at the NBER. This latter group has claimed the responsibility for being the “official” arbiter of every recession, having become the go-to outfit for determining business cycles.

What the NBER actually says about recession is that it is a serious downturn lasting more than a few months. And since GDP is one important datapoint for analyzing downturns, voila, two straight quarters of falling GDP seems a close enough distillation of the concept.

According to the group’s Business Cycle Dating Committee this week, last year’s recession lasted not even two quarters but, by their determination, just two months. The peak was February 2020, and then just March and with a trough, or bottom, in April.

It’s hard to argue with the logic and the reasons given; by almost every account, the economy went straight down beginning right at the last edge of last February, but truly throughout March extending all the way into April. Beginning in May, however, the powers of reopening, the economy was back on the mend.

Who cares, case closed, right?

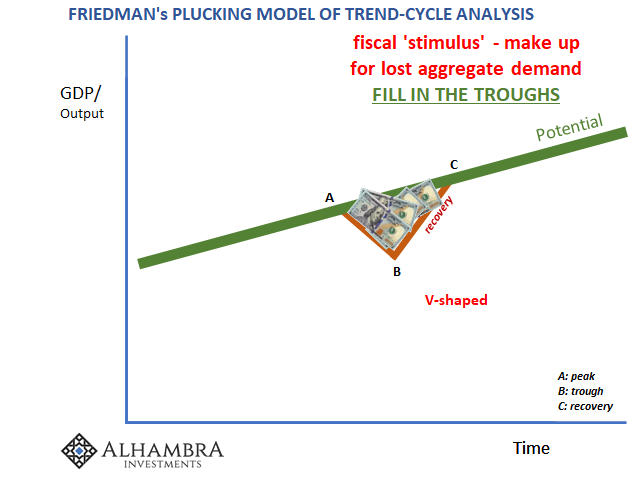

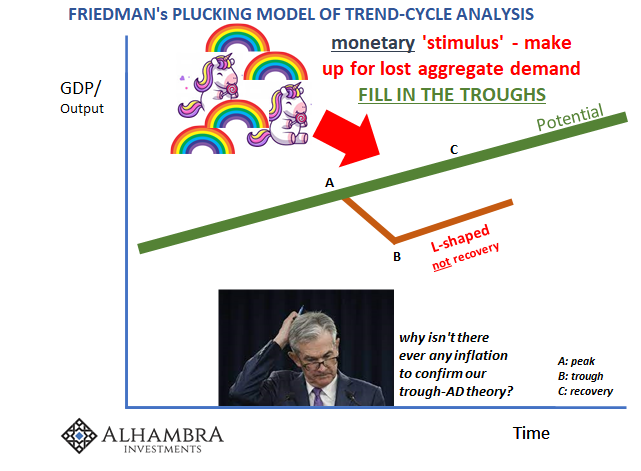

Well, there’s the issue about if this whole thing actually turns out to have been a recession at all. To the Economists at the NBER, there are only – and can only be – regular business cycles. By nothing more than subjective assumptions embedded deep within econometrics, they’ve all agreed there can be no other patterns; having banished unit roots, meaning they won’t even consider the possibility of a permanent shock.

And they’ve done so on the basis of also subjectively cleaving into a specific period in history that may not (and is proving very much not to have been) be representative of all such possibilities (ergodicity). Sure, the postwar era had been exclusively recession/recovery, but why had this been so?

To the econometrician, nothing more complicated (regressions need simplifying assumptions) than the modern stable economy with random good luck behind it (seriously, this somehow remains the consensus view).

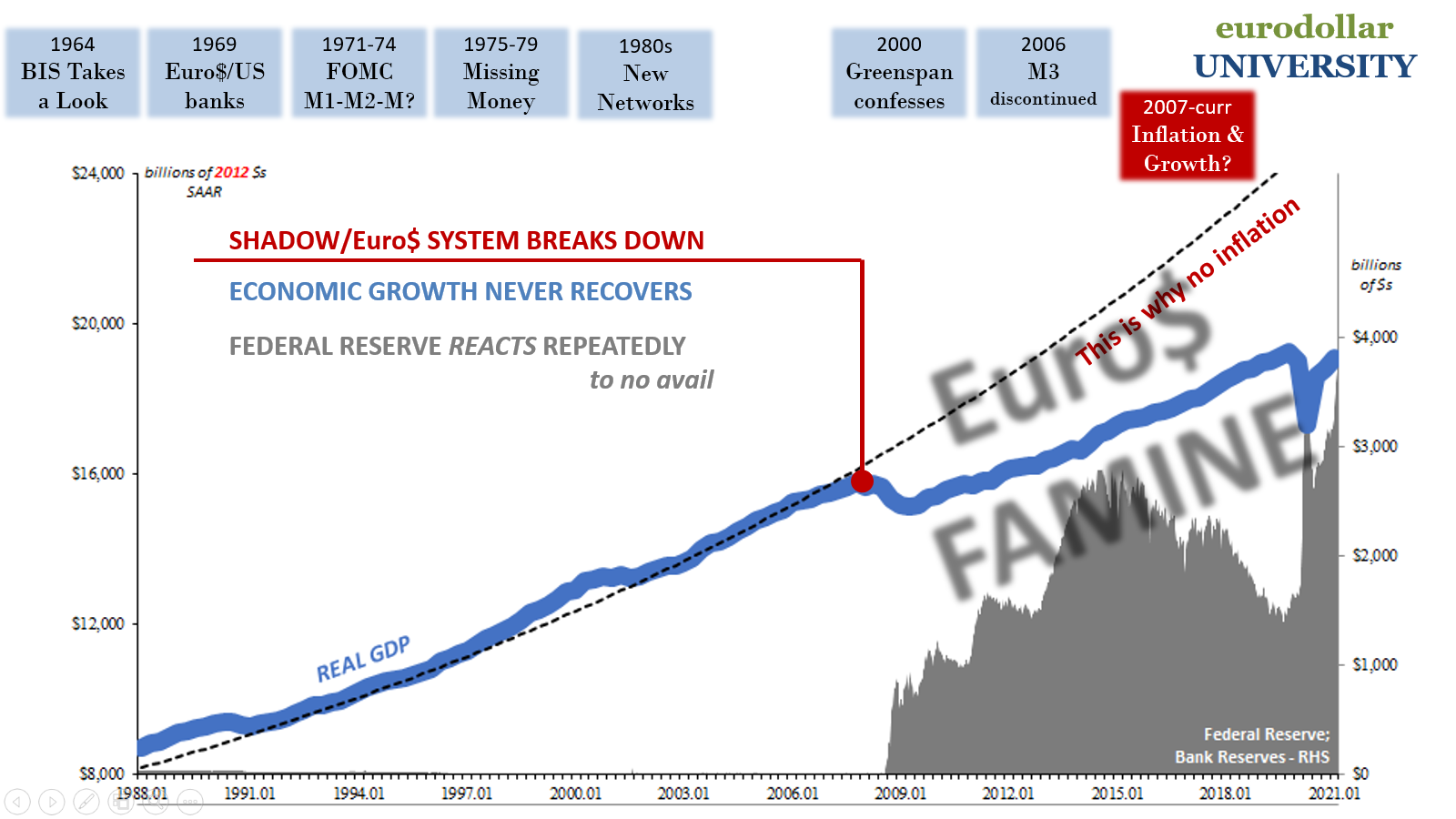

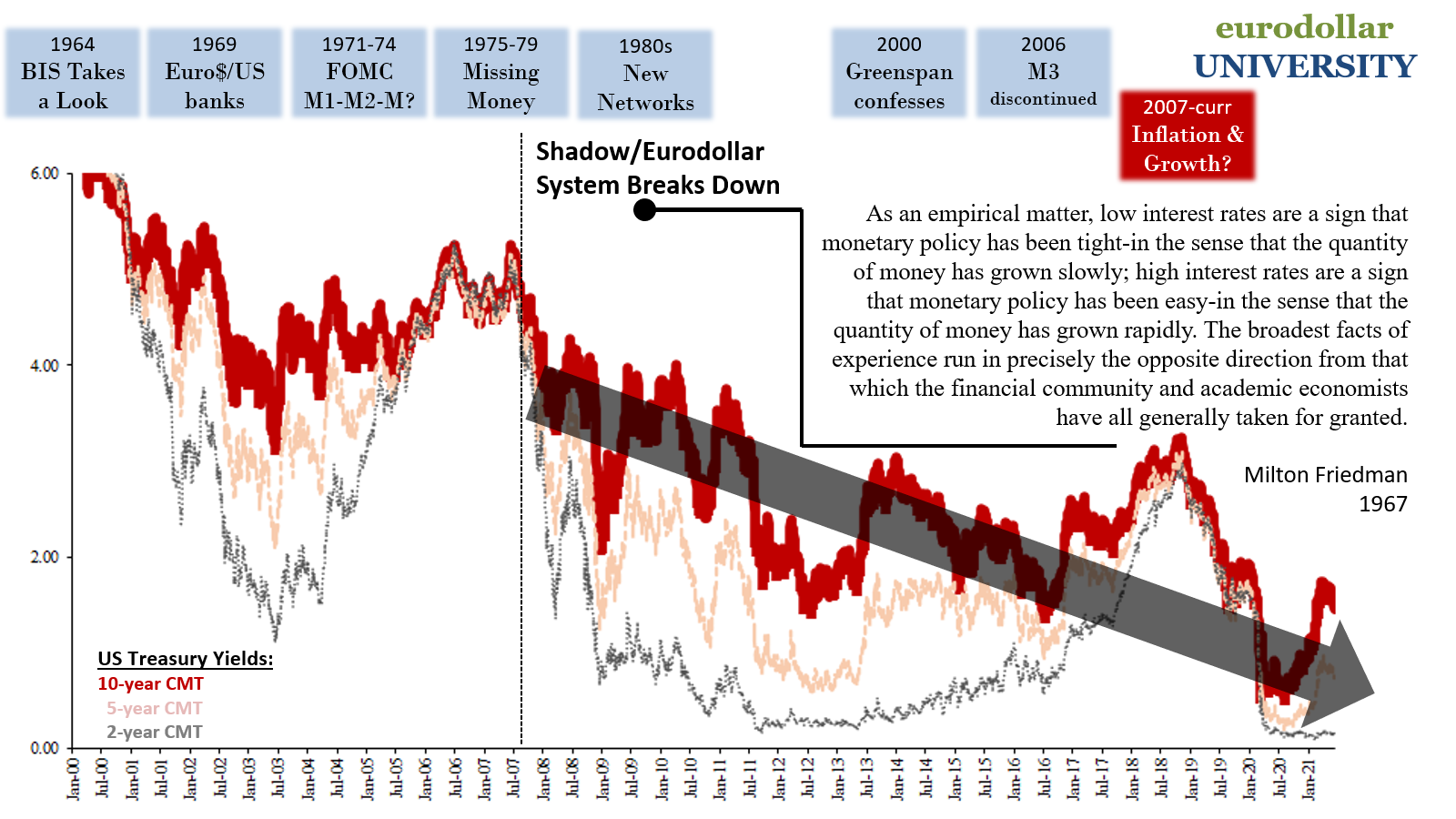

It was never monetary policy that created the Great “Moderation”, and outside of the narrow confines of orthodox definitions that period was never so moderate to begin with. As the eurodollar system built up, it only appeared that way because output was stable so long as what was hidden far out of view remained drastically immoderate. Now that is no longer the case, where the eurodollar system reverses, decays, and acts as an anchor upon global output, there is no stability anywhere. Suddenly exogenous shocks (like “global turmoil”) are the rule rather than the exception where even the US economy is concerned.

It is pretty curious, don’t you think, that for the entire span of the eurodollar system’s functioning age the postwar recession/recovery process was indeed solid. Showing up sometime in the fifties, from there onward the most anyone had to worry about was an actual build up of too much effective eurodollar money sent off to every corner of the world (the Great Inflation). With that, there hadn’t been any deflationary trouble which had before WWII so often broken down symmetry (depression).

In other words, in that beautiful isolated circumstance between the fifties and, oh, August 2007, recession/recovery was the only possibility not due to some maturation process no one can adequately explain, nor was it an effective shift in monetary policy given the Fed’s atrocious track record in fact (the omniscient central bank myth is a very recent development), thus we’re forced to consider how there must’ve been “something” else.

Correlation doesn’t prove causation, of course, but in this case there are correlations galore – each and every one pointing in the direction of offshore.

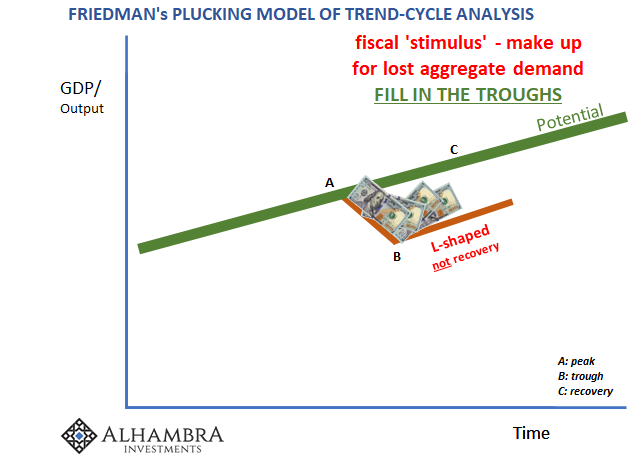

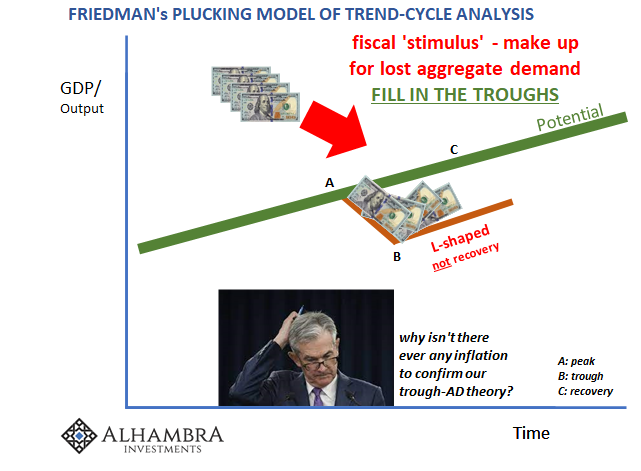

Once this eurodollar system demonstrably broke, only beginning August 2007, you can call it recovery all you want but it never lives up to the definition set out for that specific term (and not just in the US). That’s another one; the entire world’s growth trajectory deviated clearly in 2008.

What happened in 2008, exactly? Something, something subprime mortgages?

Global Financial Crisis that could only have been global and a crisis because of a global dollar shortage. And that’s the very thing econometrics leaves out of every one of its component regression equations. These Economists have no place for a monetary variable in their framework, let alone some open-ended system operating to such a huge degree way outside the domestic jurisdiction of the Federal Reserve (the stated reason for not including a monetary variable; the Fed’s got it all covered!)

Not random good fortune; willful blindness in Economics.

In other words, the issue today, as in 2010 (the NBER didn’t declare an end to the Great “Recession” until September 2010, ironically at the same time the Federal Reserve as well as other central banks around the world, especially the ECB, were flustered to find a sputtering expansion being rocked by continued “financial” issues), isn’t how long the recession had been or how deep, rather it’s become a function of recognizing whether or not the thing was actually a recession in the first place!

It’s an enormously consequential consideration hardly anyone knows still needs to be worked out. Since the NBER has only two options, recession or recovery, they only consider whether or not the downturn remains ongoing or if it has ended (trough). The 2020 “recession” clearly ended after only a short period.

Fantastic. Better than the alternative. Not really useful information, though.

The NBER’s press release says nothing about it. In fact, they used their 21st century boilerplate. The passage below is identical, apart from the identifying month, to the press release from September 2010 announcing that last trough deliberation.

In determining that a trough occurred in April 2020, the committee did not conclude that the economy has returned to operating at normal capacity. An expansion is a period of rising economic activity spread across the economy, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales. Economic activity is typically below normal in the early stages of an expansion, and it sometimes remains so well into the expansion.

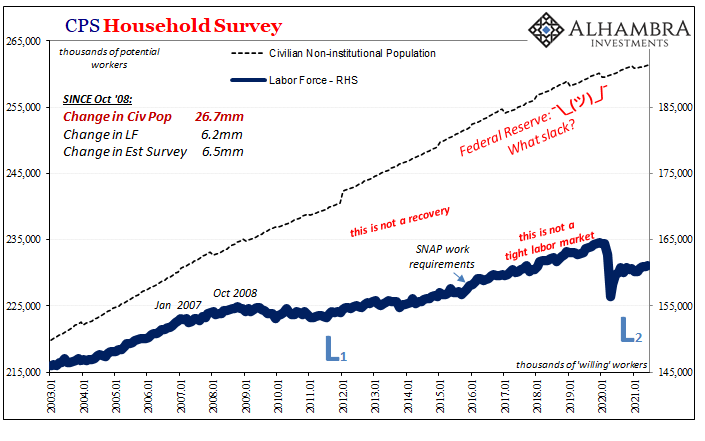

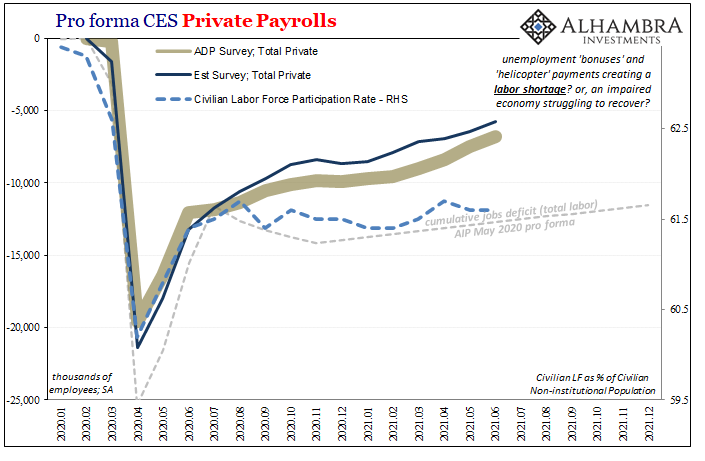

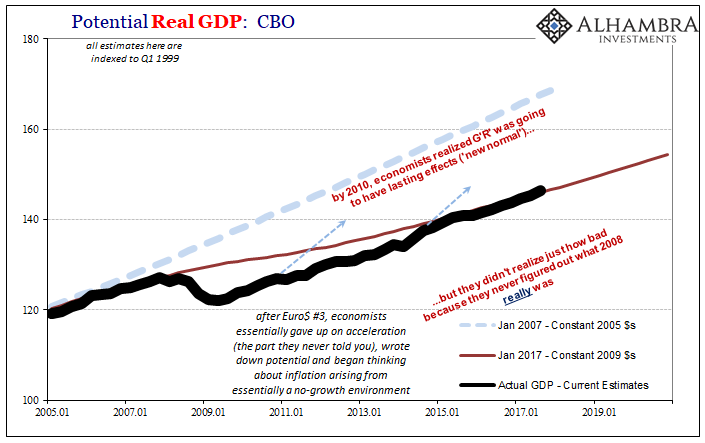

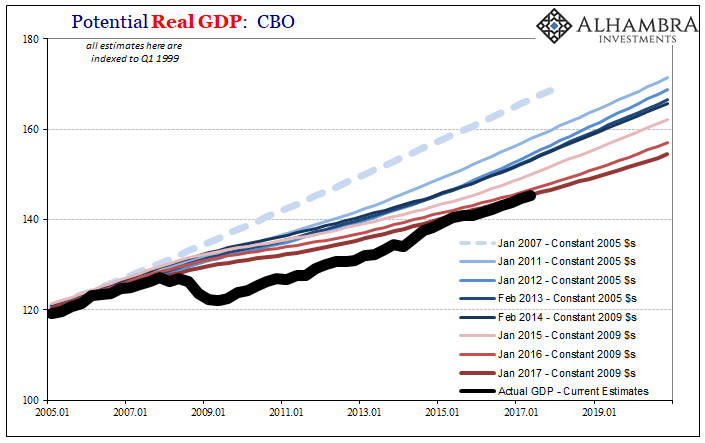

That last part was only true for the Great “Recession”; as indicated above, until 2008 recoveries were uniformly quick and, well, uniform. The years following 2008 were anything but, in every way possible. And the only way Economists talked themselves into full recovery was, first, rewriting economic potential (see: below) and downgrading it so unbelievably (literally) and then, second, narrowing down their criteria to basically a single economic datapoint – the unemployment rate.

Even using those criteria, the “recovery” still took almost a decade; or, you know, “below normal” “sometimes remains so well into the expansion.”

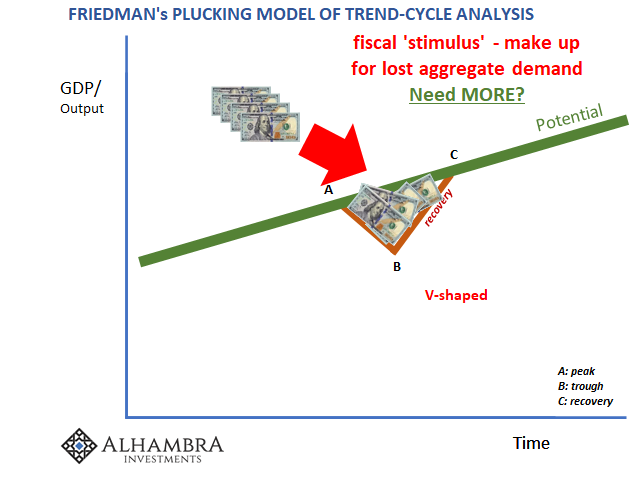

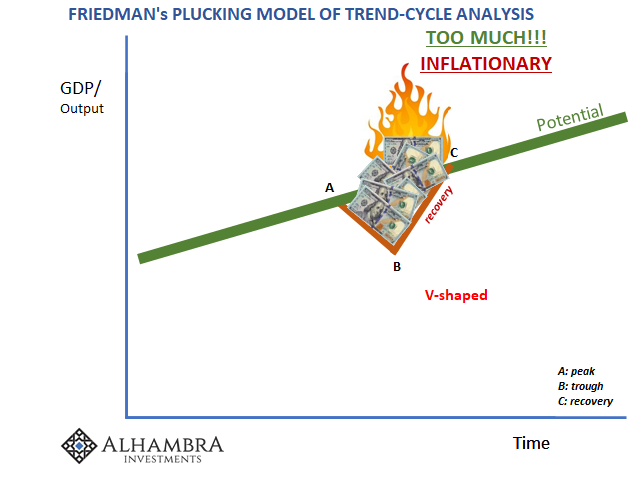

This is where the inflation “mystery”, “debate”, “puzzle” was so important; as I had written constantly for several years there, it wasn’t then, and isn’t now, really about consumer prices. Accelerating inflation would’ve been the economic (small “e”) signal that however long it took real recovery, full potential had actually been reached; that lowering and lowering calculated potential, as you see above, hadn’t been a desperate move but rather actually appropriate.

Nope. Not just wrong. Not even in the same zip code.

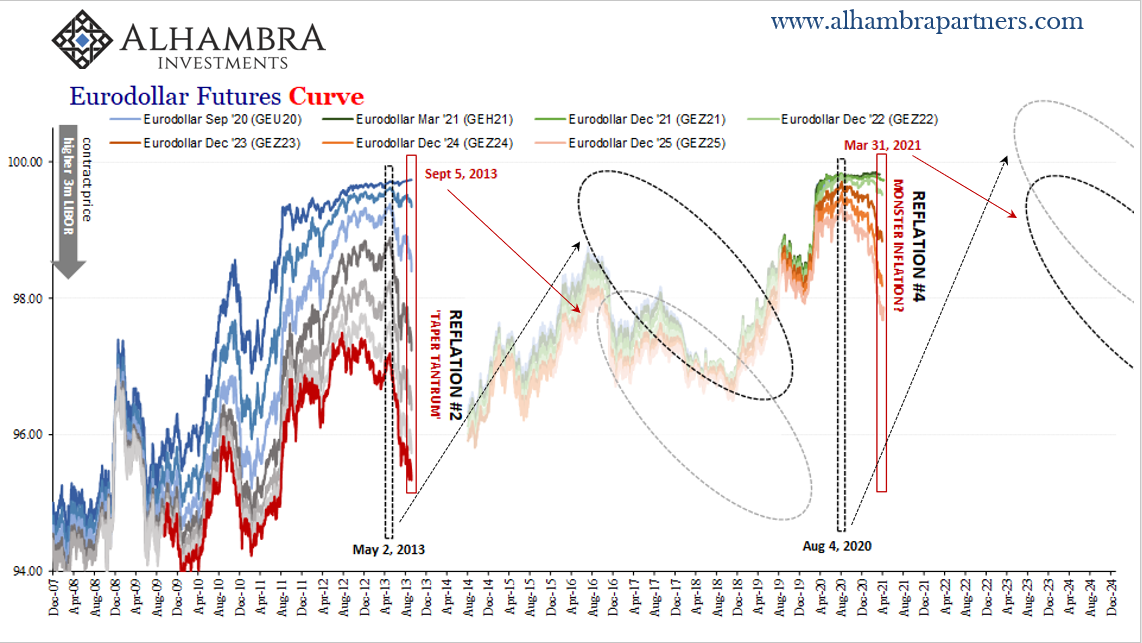

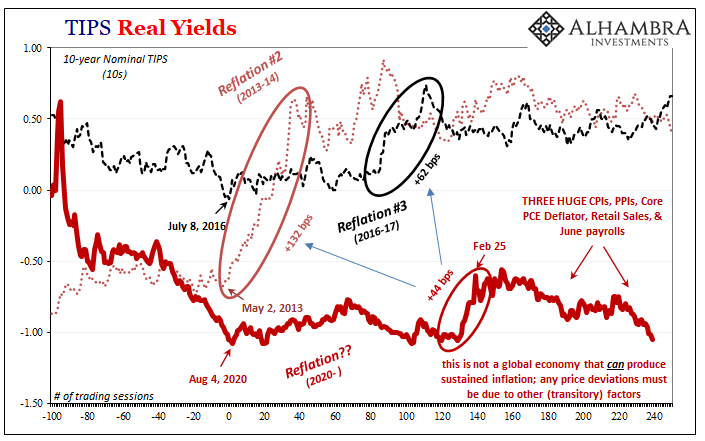

It had been interest rates and the bond market which told anyone willing to consider permanent shocks and effective monetary breakdown that inflation wasn’t happening, wasn’t going to happen, and that most importantly this meant there hadn’t been a recovery at any point following the 2008-09 contraction.

From there, so many profound implications and irrecoverably huge costs that are no longer contained to lost economy.

We can all agree on the fact there was a massive contraction in 2008. That’s easy. Was it a recession? That’s the real question, the only question.

We can similarly all agree on the fact last year there was another massive contraction. The data and evidence, however, are ominous and consistent in indicating this other one couldn’t have been a recession, either. Not just global yields, though they are making one hell of another rock-solid case.

It’s not that the NBER is wrong to declare 2020’s contraction ended. We know it did. It’s the underlying assumptions that leave basically the entire global public with too few options for what that means, and what could be happening now. The inflation case, what’s left of it, rests fully upon this NBER recovery binary just as it had the last time.

Recent history already advises a healthy dose of skepticism, for starters.

There is every reason to believe, in the post-eurodollar era, the NBER’s mainstream-accepted framework is as woefully weak and incomplete as both the last and latest “recovery.”

Recovery is still possible. It’s just not the only possibility nor is it anywhere near the most likely one as comprehensively suggested by pretty much everything across-the-board – whether the NBER gives us their approval to recognize they are using such an incomplete picture to confuse and even fool the global public.

Here’s the only “equation” you’ll need for the foreseeable future: (Permanent Shock) ^ 2 = NOT GOOD.

Stay In Touch