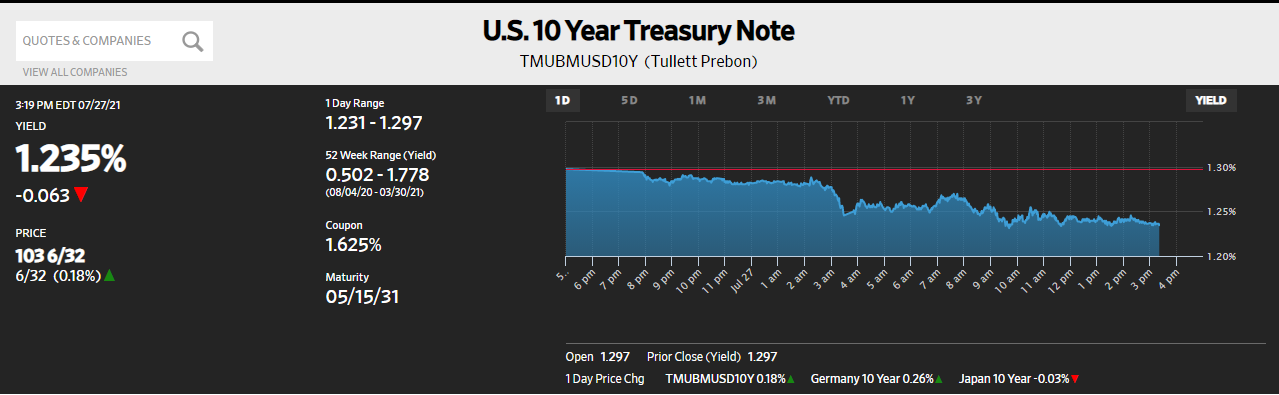

We’ve spent months in US Treasury bill yields for a (very good) reason. There’s brewing trouble out there, and it’s not just caught the attention of overeager indirects bidding in UST bill auctions. The premium for those instruments is a nod toward growing collateral scarcity, a deflationary potential that is almost certainly a big part, probably the key part, behind diving bond yields.

This scarcity of collateral has even caught the partial attention of the top policymaker at the Fed (not that Jay Powell knows what more to make of it, or how serious it can get).

For the brief notice at that central bank, the “not a lot of T-bills” is for its worldview a product of Janet Yellen acquiescing to Congressional stalemate (she obviously has no other choice). In other words, Treasury is refunding bills ahead of the debt ceiling when private market demand for them is already high, putting the squeeze on the market.

Is that it, though? Involuntarily restricted issuance and nothing else?

No. One need only witness the regular trade of front-end T-bills priced to yield less than the Fed’s RRP. Today another good example; for much of the trading session, every single bill maturity up to 6 months priced to rate below an equivalent of five bps. The sub-5 for each indicates an inarguably valuable utility that we’ve seen time and again connected to wider collateral concerns beyond supply-driven scarcity.

The simple version is simply risk-aversion in money dealing. It sounds straightforward enough, though in practice anything but (thanks, QE). And in terms of collateral, this can mean dealers growing shy about re-using, repledging, and rehypothecating collateral of all kinds; particularly in any transformations or other securities lending arrangement which begins with the junkiest formats.

To put it simply, the collateral multiplier ends up shrinking driving the edges of the entire global system toward what’s left as efficiently usable; herding the collateral-hungry into the best, more pristine issues. Bills are at the very top of this list.

Thus, collateral supply problems at both ends; Treasury issues less of the best of the best while risk-aversion deprives the outer rims of access. In this latter sense, collateral scarcity among the riskier components via a shrinking multiplier, it therefore contributes serious weight to demand for better collateral. Not just bills, also longer-term notes and even some bonds.

LOL

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) July 16, 2021

(Spoiler: deflationary money; collateral; we've done this four times already)https://t.co/p6AgaFreVR pic.twitter.com/L7kKqehrPq

At this point, they're aren't even trying. At least they're inadvertently being honest about not being honest. Just invented some "test" that no one would ever consider.

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) July 22, 2021

This just isn't analysis, it's pure inflation propaganda.

ICYMI, UST yields are substantially lower today. pic.twitter.com/Rf3bmXBsKw

Risk-aversion? This isn’t something anyone takes seriously in the mainstream media (which continues to report on the drop in bond yields globally as if it has been some “baffling” mystery). Where and why would dealers become averse in the first place? The whole idea is directly at odds with the inflationary hysteria still gripping virtual commentary.

Unable to present realistic answers, it’s easy to think this might be delta; as in corona or COVID. With another looming overreaction to case counts, this might make some sense. After all, what triggered both the GFC2 and last year’s historic recession?

While this sounds like a plausible theory, trading early this morning presented another much more realistic alternative scenario.

China.

Like last Tuesday’s scramble for collateral, the trigger in Chinese overnight trading was nearly that perfect:

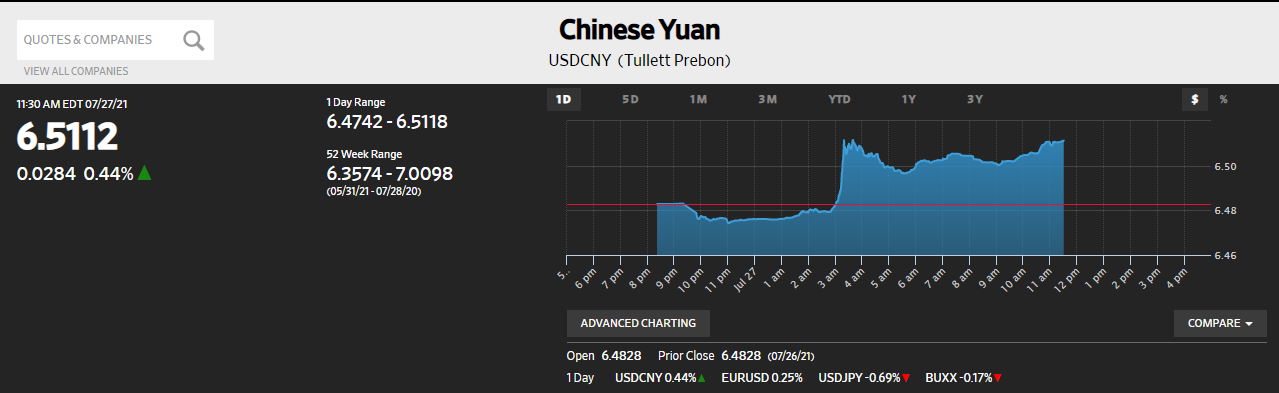

At 3am EDT, China’s yuan suddenly tanked against the dollar (for those not familiar with the easiest of our eurodollar equations, CNY DOWN = BAD). US Treasury yields and counterparts in places like Germany’s bund market had already been tilting downward beforehand, though very modestly.

But with CNY tumbling so dramatically it produced the knock-on effects in the deflationary direction for UST rates. This wasn’t COVID.

Instead, more and more it has become clear that “investing” in China carries serious risks; political primary among those. Government regulators have been cracking down on various parts of their economic system, with a special recent emphasis on tech. Last night, it was private educational firms in China who drew unusually specific Communist ire.

This has, by and large, left the mainstream stumped. Why such a heavy hand and why now?

So what has changed? Like many other nations, China is waking up to the fact that data is the new gold and it needs explicit rules to govern how it is accumulated and shared. In April 2020, China released a policy document that significantly listed data as a “factor of production” alongside the four traditional factors of socialist economic policy: land, labor, capital and technology.

Oh boy. This was Time Magazine’s way of admitting those writing analysis for it have no real idea. Suddenly an overtly authoritarian set of measures focused on the flow of information is some newly discovered economic focal point for Socialism with Chinese Characteristics?

The direction China’s Communist government under Xi continues to take should not have been a surprise to anyone. Unfortunately, most people aren’t aware of why that is. And the government’s rising interest over the overall flow of information given what’s been transpiring over there, this just goes without saying starting from a more realistic premise as to the real state of the Chinese State.

And what is that? Here I’m going to borrow heavily from what I’ve previous written over the last four years because it has, I believe, stood up exceedingly well to the passage of time, establishing a serious degree of credibility (science: making predictions and observing evidence). Beginning with this from December 2018, as Euro$ #4’s “unexpected” landmine was in full destruct mode:

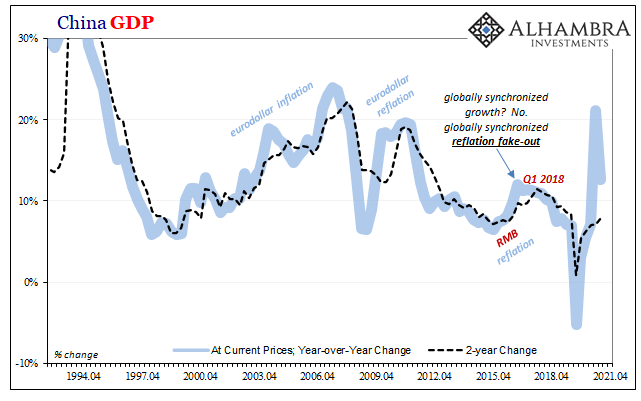

China simply has, as we’ve been writing and speaking about for half a decade (and more, less specifically about China), no monetary room with which to get any kind of internal growth started. That point was driven home last year. The global economy despite all official protestations everywhere has never once picked up toward recovery.

Therefore, the Chinese government is left between the rock (external malaise) and the hard place (no internal monetary space). Only a few months after June 2017, Communist officials convened at the 19th Party Congress and “elected” to move authoritarian. This, I don’t believe, is mere coincidence.

Going back to that 19th Party Congress, back in time to October 2017 when over on this side of the Pacific there was near-certainty, as there is now, global growth (synchronized!) was about to accelerate wildly and bring with it a masterful bout of inflationary recovery. Instead, Xi and his cabal were telling you and anyone else who’d hear them out this was never the case.

Much worse, they were prepared to stake their entire regime on it. About a week after it concluded, late October 2017, I wrote the following in summary:

For totalitarian states this is the standard order (and for a good deal too many “democracies”, too). A leader is always looking to tighten his grip on political power because despite the love affair for authoritarianism (especially in the form of technocracy) in the West that kind of system is uniquely fragile. Like an organized criminal operation, the real danger is most often from within the power base rather than from the people outside of it.

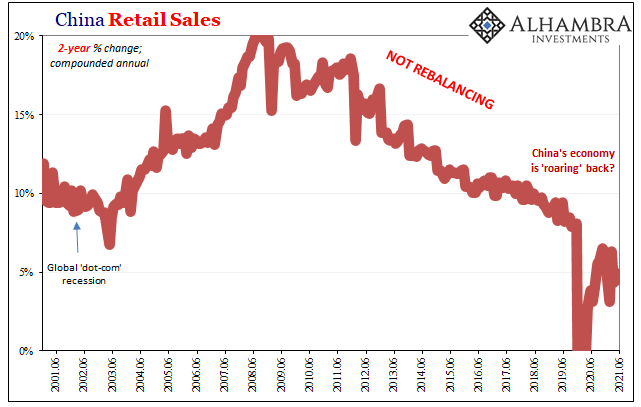

I can’t help but wonder, however, if what we are seeing here in the 19th Congress is designed instead for that other case. China’s great challenge has been for the last quarter-century to modernize not just as a matter of economics but more so social progress; to take the peasants out of their subsistence lives and given them a shot at middle class progress and even luxury. Economically satisfied citizens are a far better long-term proposition than a politically unstable peasantry prone to fits of righteous anger.

The Chinese system of just such transformation has been partially successful (thanks in huge part to the eurodollar, when it was working). In terms of human history, it has been wildly so, for no nation has ever undergone such massive transformation in such a condensed fashion. But it isn’t yet enough, or so we think – or so China’s politician’s think?

To forbid political challenge to the country’s leadership is one (potential) method for at least raising the costs of turning grave economic dissatisfaction into something more substantial. It seems more and more that authorities over there are battening down the hatches, not opening themselves up in a way that a more optimistic and bright future would lead.

These two “factors” are, like it or not, inextricably linked; increasing authoritarian steps alongside decreasing confidence in economic sufficiency which likely falls well below needed levels to have continued that former economic transformation. Without the growth, those quantities of growth, “at risk of turning grave economic dissatisfaction into something more substantial.”

What better way to nip any such righteous anger in the bud than to control the flow of information more tightly? The less the economy, the more need for nipping.

The Chinese in 2021 are merely following their own 19th Party Congress playbook, the title of which is Managed Decline. That’s the plan, anyway.

Today, the financial media is filled with stories about the shock of all this tech cracking down and how it will possibly affect overseas investors or whatnot. Completely missing this overriding big picture, the multi-year effort continues to push the boundaries of totalitarian behavior at the same time the Chinese economy grows only darker and darker.

Of the more short run parameters, these are coming to a head in 2021 as growing risk aversion from the parts of the system – the only ones that really matter – never needing mainstream confirmation they already know doesn’t come about until after something happens.

Listen to Xi. The guy, unlike Western media, has been totally open about what he’s doing and why. I mean, seriously, what did everyone think he meant in October 2017 when: 1. He explicitly made himself Mao-like; 2. Xi then followed that right up announcing an unparalleled policy shift from “quantity” to “quality” economic growth (as if there was such a thing).

Nearing in on four years later, managed decline – and all it entails – remains right there out in the open for anyone to see. It’s in China’s economic numbers; it is all over these increasingly feudal political “gestures”; these are embedded in the deflationary potential for the global economy; and each understood in this way by specific moments and local trends in markets like US Treasuries.

In short, as has been the case for a very long time, the Chinese are still preparing for a very rocky (deflationary) future, not the unwise and unsupported rollicking (inflationary) outlook blindly accepted as foregone.

The great tragic irony, of course, in the latter is just how much it absolutely counts on and requires China to economically and politically ignite and support that very inflationary outcome. Sure didn’t work out in 2018, either.

Stay In Touch