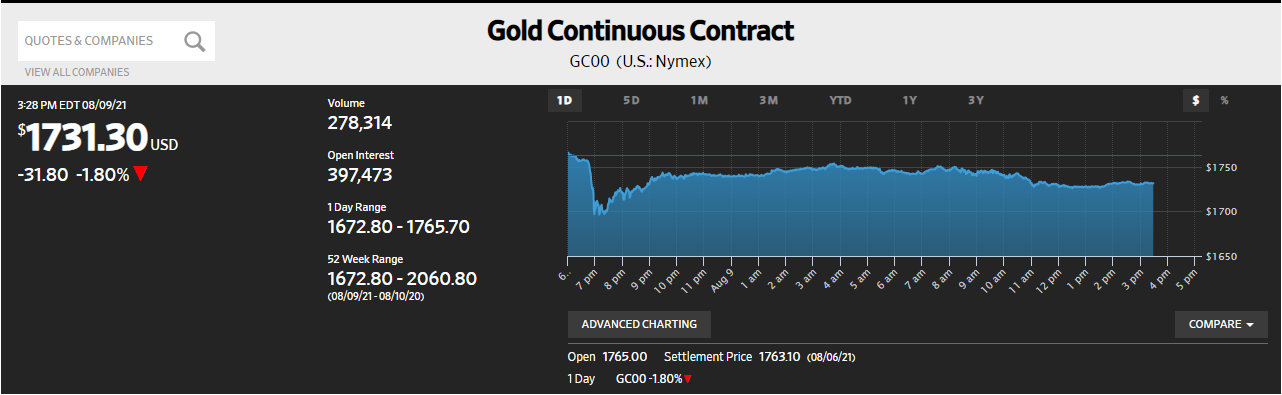

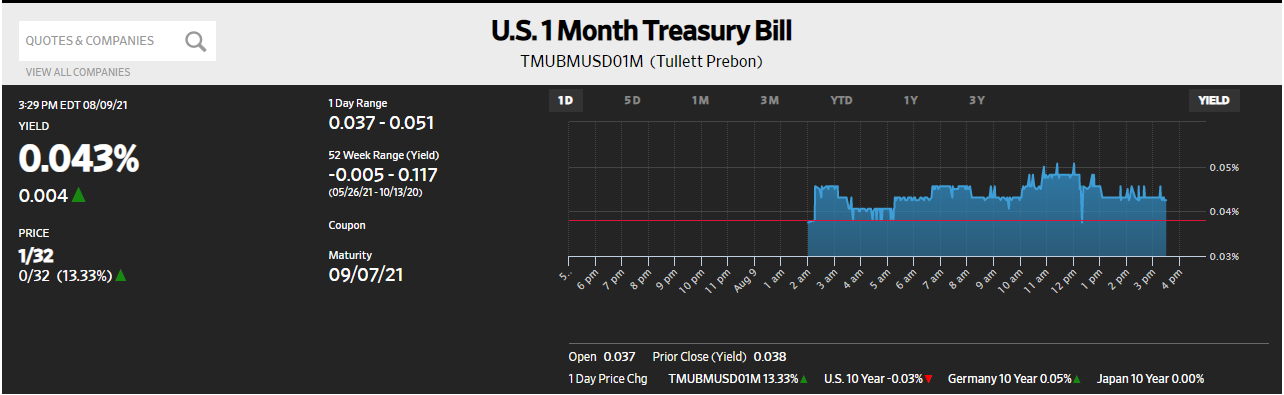

This one wasn’t nearly so perfect as the scramble for collateral had been a few Tuesdays ago. Last night’s, however, did have a sizable, visible contribution from the gold marketplace. That’s a significant tell even if it didn’t necessarily correlate by the minute with T-bills and other collateral numbers.

In this instance if only because the gold “slam”, which was enormous, took place the at very nearly the earliest instance it possibly could have. T-bills joined in the scramble once they could. Sunday night trading:

Or, in Asian terms, Monday morning in China. There hadn’t been any major economic news released at the time gold crashed. The CPI/PPI estimates which came out weren’t published until 930am Beijing, or 930pm EDT.

Instead, if economic accounts were considered in collateral chains as risk aversion (growth “scare”) acting on dealers (shortened collateral multiplier), then what happened Sunday night/Monday morning would’ve been the export and import estimates China’s General Administration of Customs had reported early on Saturday morning local time.

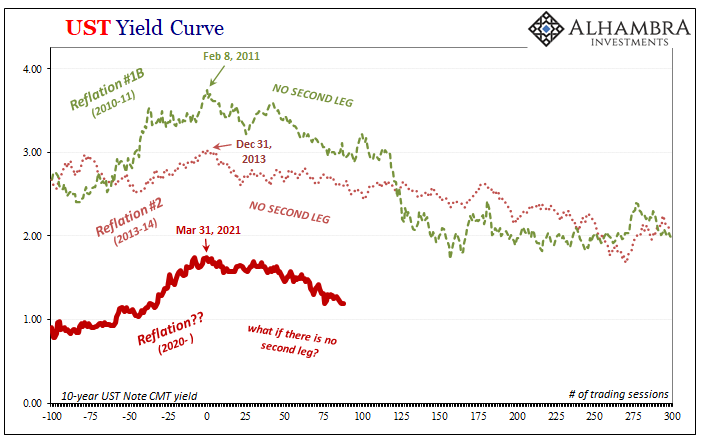

It didn’t really matter either way, as both sets inflation as well as global trade each suggested the same thing. And it was, rather is, what’s been at the forefront of upsetting the delicate reflationary balance and tipping it back into the non-inflationary direction closing in on six months.

What if the global economy’s rebound from last year’s deep recession has already seen its best days? Since the “best” of the rebound hasn’t actually been all that good, not in the context of either that contraction or past history, then this raises an entirely uncomfortable and concerning array of problems only beginning with some regional renewal of COVID mania.

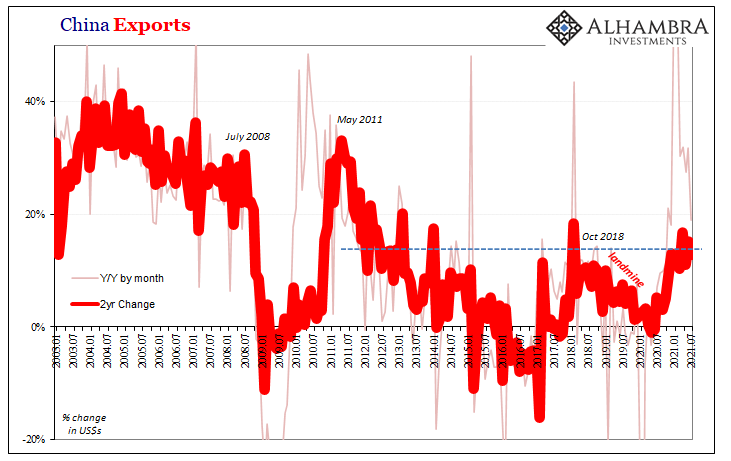

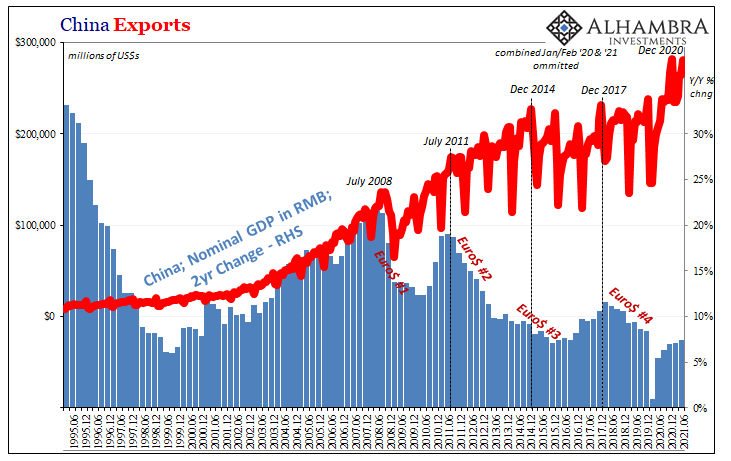

The bland statistics don’t really tell the story. Beginning with outbound trade, exports leaving China were thought to have been worth $282.7 billion in US$s during July 2021. This was 19.3% more than exports had totaled during July 2020, but more importantly only 28% better than what had been shipped out back in July 2019.

The 2-year change at an annual rate dropping to around 13% last month.

It’s not disastrous or anything other than hugely disappointing; where is the promised unambiguous upside? More to the current relevant point, the peak statistical change was registered, for China exports, all the way back in December last year; thus, July another month without meaningful acceleration, or stuck at basically the same as the past seven-year stretch (above) of not nearly enough.

Not enough adds much to these growing concerns about 2021 and beyond.

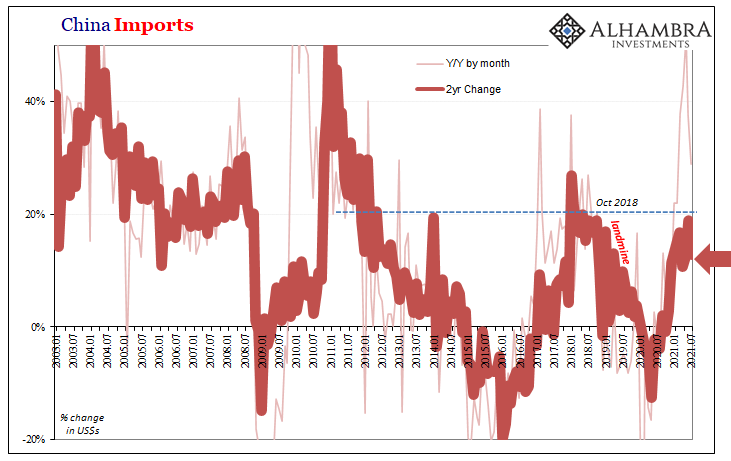

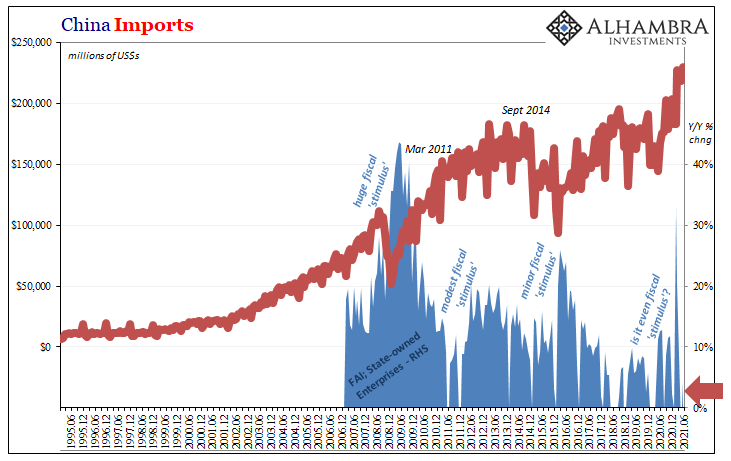

As do China’s imports which, in the end, may mean more insofar as the global economy downstream from them is concerned. Again, the annual rate starts out impressive; rising 28% year-over-year to $226.1 billion in US$s. The 2-year increase, at an annual rate, not quite 13% which, as you can see below, is way below what rate China “should” be demanding of the resource-rich economic followers in a real recovery scenario.

This is not a recovery even at its best rate, the same like exports that goes back into last December. Having indicated a possible topping out both sides of Chinese trade, the idea was further supported by the later Monday morning (Beijing time) release of the price data while gold was recovering.

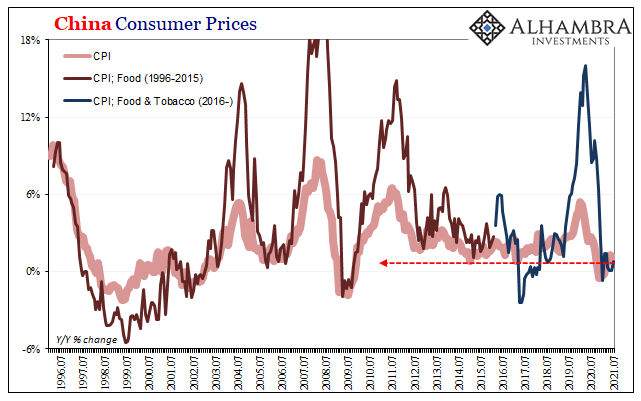

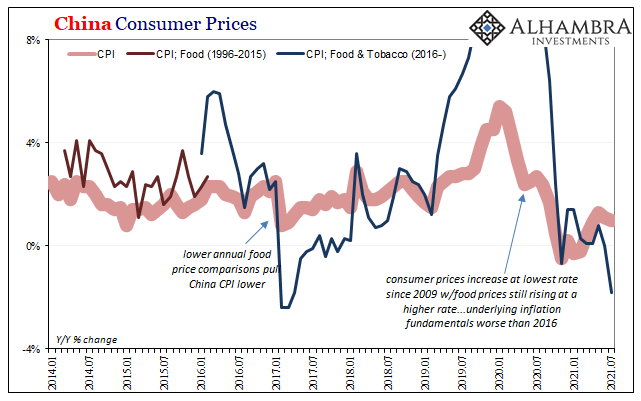

Inflation Hysteria hasn’t quite cooled too much even as so much of any potential for sustained real inflation (or any outside the US goods economy) depends upon the real state of China’s system. In terms of consumer prices, beginning there, the rate of increase for the Chinese basket has slowed for each of the past two months after having peaked back in May (a repeating occurrence).

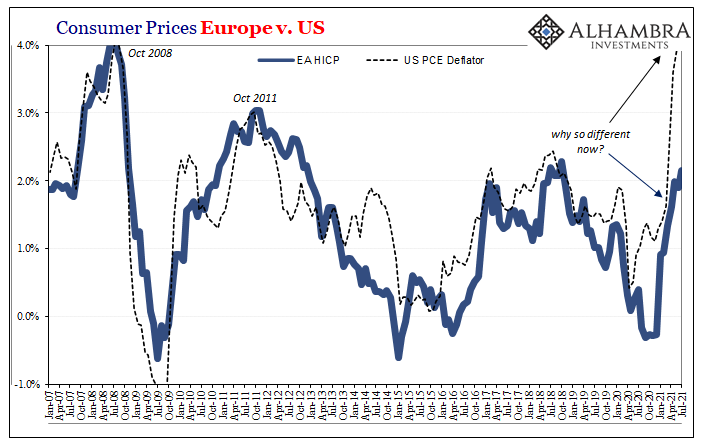

Consumer prices rose only 1% year-over-year, already relieving us of any necessity for a 2-year comparison. This was among the lowest in the past decade plus, meaning that price behavior in China joins the vast majority of price behaviors around the world which look nothing like their American counterparts (the US CPI and others true outliers).

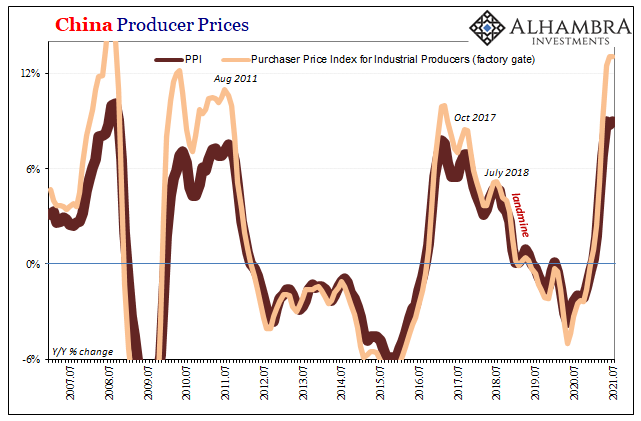

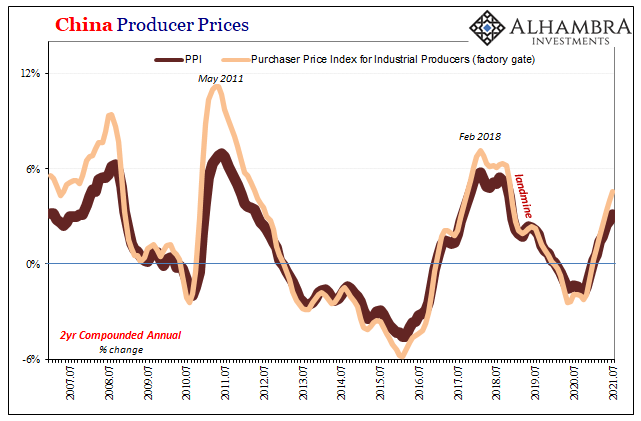

Even producer prices in China are far less, potentially peaking, too. While the PPI did rise 9% year-over-year in July, it hasn’t accelerated since May (when the rate was also 9%). Furthermore, both the PPI and factory gate indices were heavily influenced by base effects; much more than in either the United States or Europe.

Two-year changes in them (at annual rates) weren’t even equivalent to 2018’s previous peak rates (before Euro$ #4 slammed them downward). And now it is beginning to look like 2021’s may have also peaked:

The picture which is consistently emerging from China is otherwise pretty clear even if unwelcome and contradictory to the inflation/global money flood narratives. The US economy may, in some specific parts, appear to be hot even overboiling with inflation potential.

That potential, however, is actually depending upon the rest of the global economy – beginning with China – for what could last beyond the influence of artificial, temporary factors.

And if the global rebound’s best days are already in the past, no wonder anyone paying close attention might look ahead with increasing angst. If so, it would make perfect sense how they have to force more monetary disruption in the meantime while repositioning for rising more emerging downside risks.

Stay In Touch