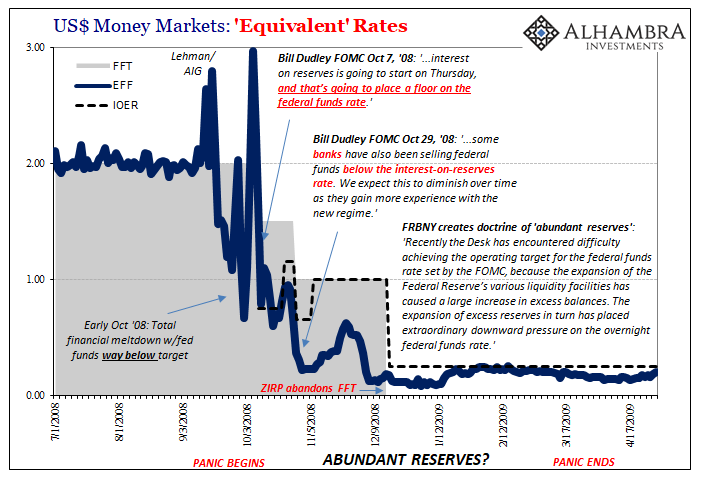

A momentous day, for sure, but one lost in what would turn out to be a seemingly endless sea of them. October 8, 2008, right in the thick of the world’s first global financial crisis (how could it have been global, surely not subprime mortgages?) the Federal Reserve took center stage; or tried to. Having bungled Lehman, botched AIG, and then surrendered to Treasury which then screwed up TARP, the world’s entire financial edifice was burning down while US policymakers (they aren’t central bankers) debated just how certain they were IOER would put what they concluded was a badly needed floor under a federal funds market afflicted by a sudden overabundance of reserves.

No, I am not making this up; worst crisis since 1929 and the Fed’s people were thinking a whole bunch about “too much money.”

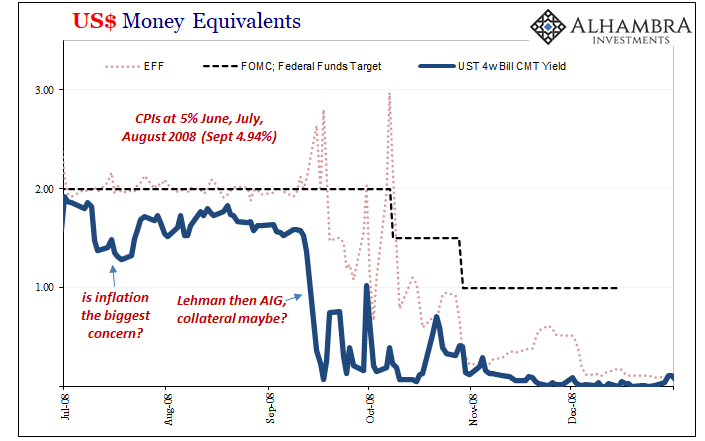

In addition to IOER (the joke), the FOMC also voted for an emergency rate cut on October 8, a 50 bps double bringing their target down from 2.00% to 1.50%. The effective federal funds rate that day was 2.24% (pulled upward initially by LIBOR, the 3-month rate then 4.52% and not done yet) before plummeting to 1.40% on October 9 and then 0.79% on October 10 (so much for IOER).

If that wasn’t enough to convince anyone of both the futility of these “monetary” policies as well as the total incompetence of those conceiving them, in addition to, you know, global financial crisis, it was even crazier and more extreme in the Treasury bill market. The 4-week instrument, the closest to the shortest-term money markets and their most equivalent substitute, had skyrocketed in price bringing the yield down to just 23 bps on that same day (having been as low as 15 bps two days prior).

The 4-week equivalent rate would drop again, getting down to 7 bps by October 10 as GFC1 reached its most acute destructiveness (not coincidentally, since the Fed’s actions during this period achieved nothing of consequence, bill rates would see zero and even the occasional secondary market minus in the weeks and months ahead).

In other words, not just collateral scarcity but the maddest scramble for it in living memory (to that point).

What about the other end of the curve?

Well, on October 8 it was also a hugely unusual day for Treasury. The federal government’s debt agency just so happened to reopen the 10-year auction four times on that one single day! And what a day because the market didn’t seem to want them. Or did it?

This after Treasury had said the entire reason for reopening these various 10s was because they had become so scarce and highly sought after. Yet, by the time the reopening auctions were conducted, they weren’t any longer – according to secondary markets.

What the hell was going on?

This, not March 2020, was actually the first instance of global dollar liquidity becoming so bad, so unreliable and expensive for nearly everyone, dealers had, like they would last year during GFC2, pulled regular offers for any repo collateral that wasn’t directly OTR. Because of collateral problems it seemed like even the vaunted Treasury market was in danger of falling apart (it was, though having less to do with “the Treasury market” than the utter failure of the Fed to arrest and correct global dollar elasticity in all these other non-standard, non-textbook forms).

The 10-year auctions issuing new OTR (on-the-run) notes were perfectly fine and well enough received. But secondary market securities, those OFR (off-the-run), not so much (foreign selling). In fact, the 10-year published yield – derived from the latter class – surged on October 8 from a close of 3.50% (Oct 7) to 3.72% the same day as the Fed’s 50 bps rate cut, and with the 4-week bill already ridiculously low (yield) and trending downward.

Haywire. Hysteria.

Confused by seeming contradictions all over the place (massive global inelasticity will do that), the media could only offer a shot in the dark excuse for secondary Treasury market price action. From Reuters on the chaotic afternoon of October 8, 2008:

U.S. Treasuries prices plunged on Wednesday, sending benchmark notes over two points lower on expectations of a flurry of new debt supply and after a tepid reception in an auction of an older 10-year note issue.

Note their word “tepid”; it wasn’t out of line at all with prior auction results from September (pre-Lehman) and August. But what else could it have been?

The breakdown had to be supply fears because understanding otherwise such a thing in the long end of the Treasury market would point the sure finger of blame back squarely in the direction of Ben Bernanke.

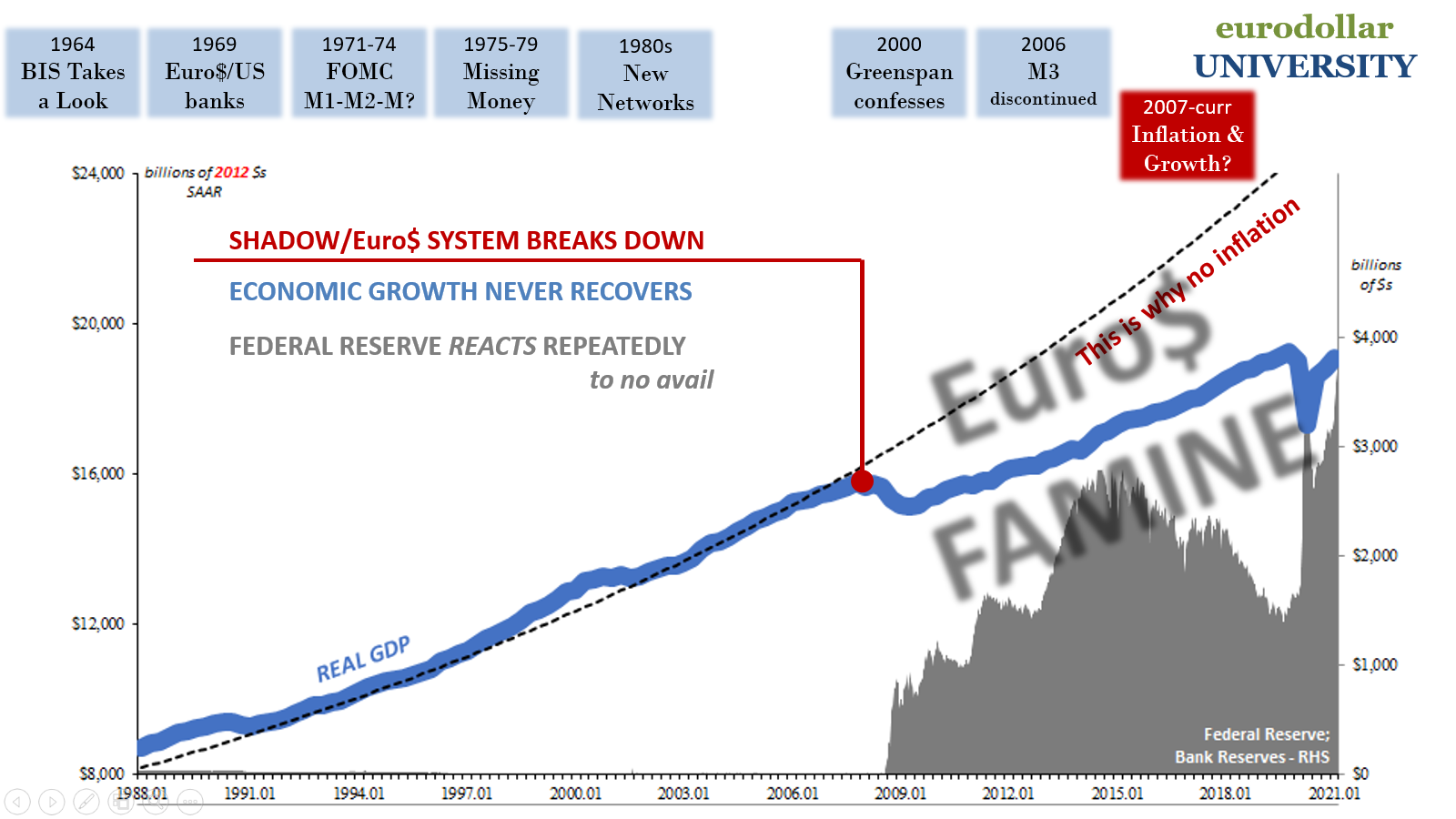

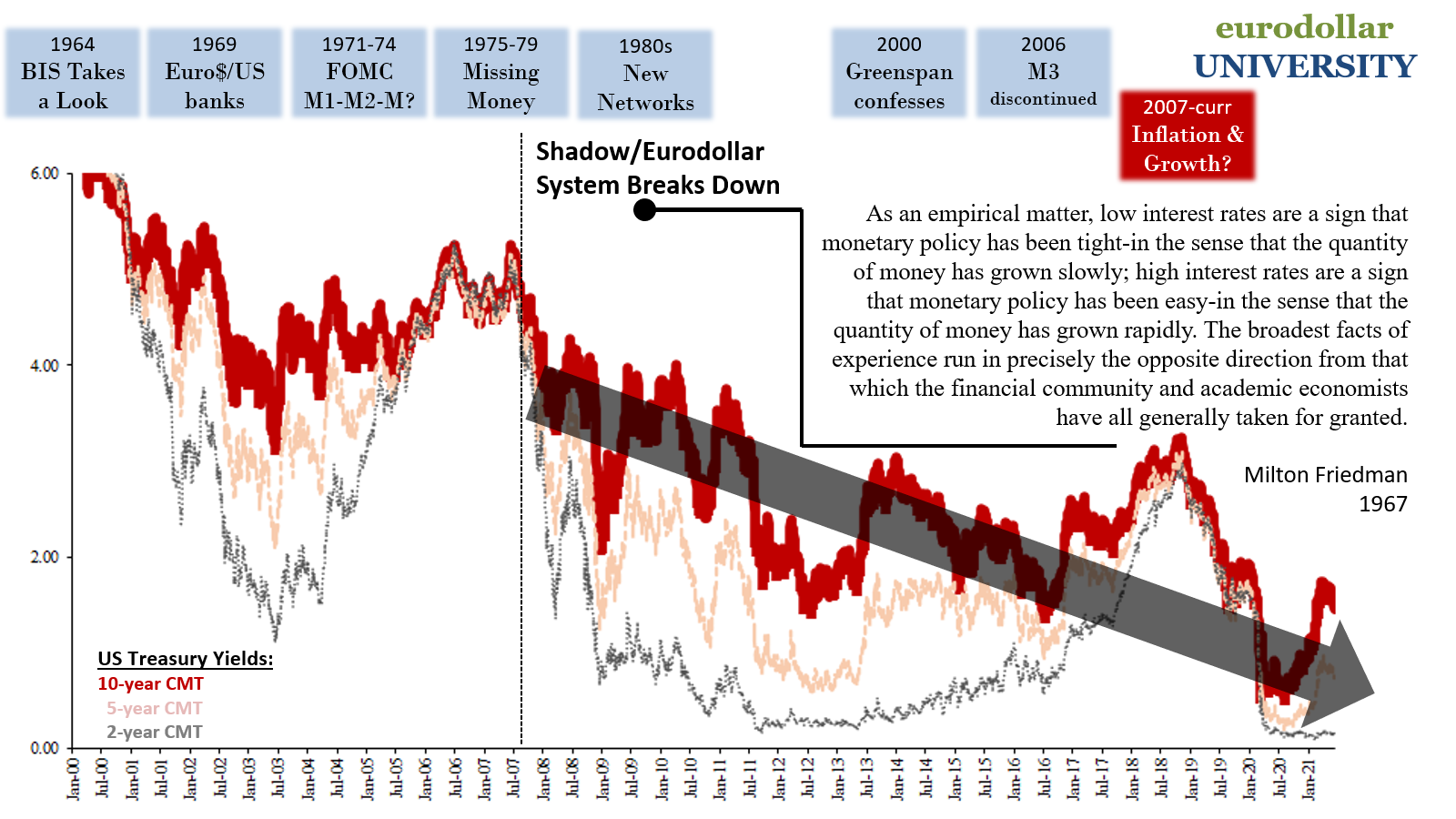

Nearly thirteen years later, Treasury’s supply of 10-year notes (and all others) has only exploded by an order of magnitude – and yet, confounding all vigilantes (being one myself), prices for them have been bid forever, it seems, higher; yields lower and lower and lower.

To many, the discrepancy must be again attributable to the Federal Reserve (QE in this case, all that bond buying). But like this anecdotal nugget from the 2008 disaster, doing so is pure reflex rather than rational thinking and analysis (we’re all taught everything is about the Fed when almost nothing is, monetarily speaking). In fact, the evidence – from everything about the crisis to everything which has followed from it – demonstrates conclusively just how openly cultish such belief is.

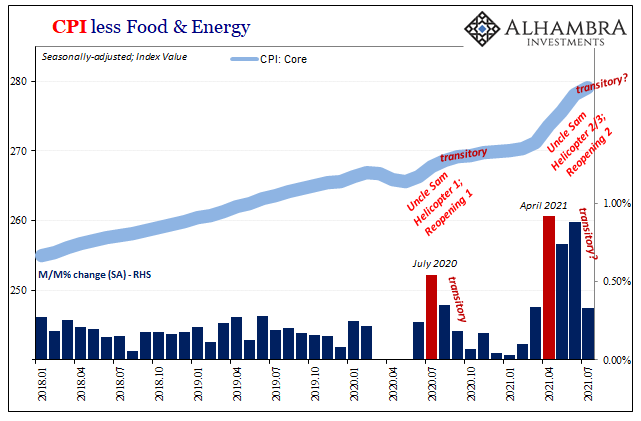

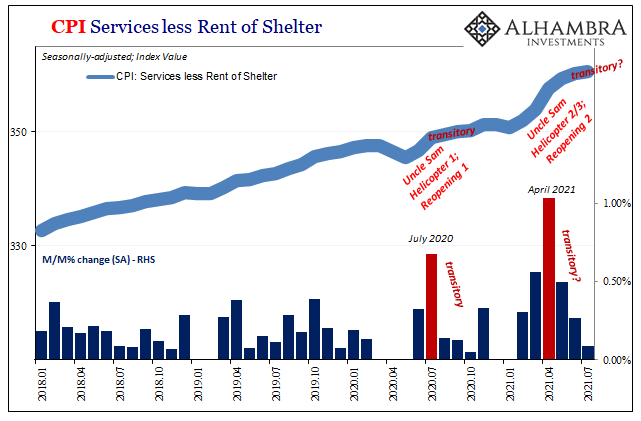

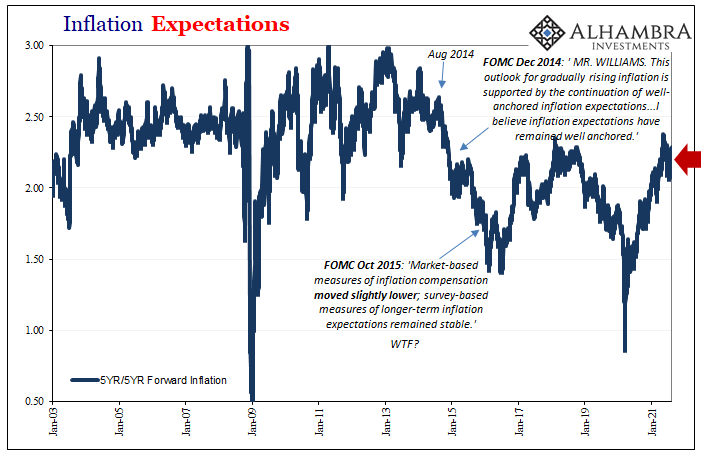

This includes, obviously, inflation. A monetary phenomenon, defying both “too many Treasuries” arguments as well as “money printing” criticisms, inflation has failed to materialize over the years in between.

Interestingly enough, the last time there were two monthly CPI’s better than 5%, the year was…2008.

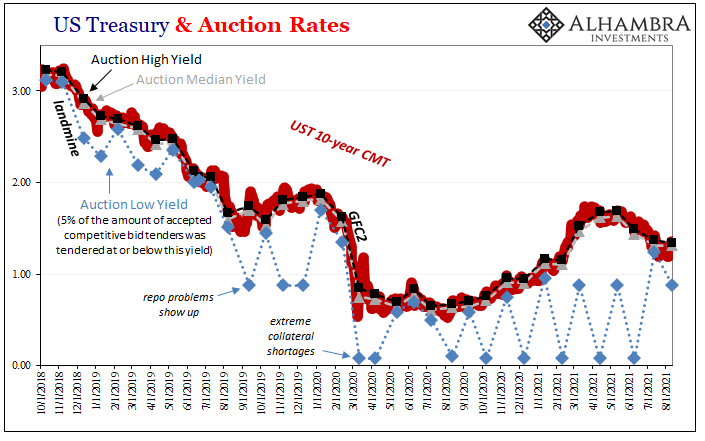

So, how do we reconcile the fact that over the last two months (June and July 2021) the US CPI has finally repeated that 2008 feat; two in a row greater than 5%? Treasury yields – consisting of growth and inflation expectations – are today confoundingly tiny by comparison. The 10-year around 1.34% substantially less than what would have been a record low before last March’s eerily similar Treasury OTR/OFR bifurcation.

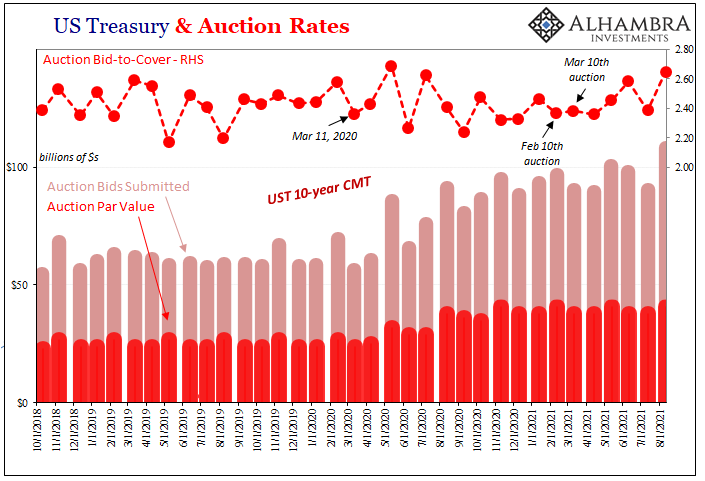

Before answering that question, we need to first note that today the Treasury held another 10-year auction which just so happened to be the same day as the CPI report. This time, demand for it was the opposite of “tepid” despite even more serious supply concerns (“infrastructure” anyone?), another 5% CPI, plus a steady stream of hints from Fed members about “tapering” bond purchases.

The short answer is: things are far, far more complicated than the textbook allegation which claims the Fed controls everything with the easy flip of a switch (actually, moral suasion, the textbook says the Fed doesn’t even need to flip any switch, it merely needs to suggest the possibility to the market).

The more thorough answer is: the textbook needs to be entirely rewritten from the ground up. Beginning with collateral and actual monetary needs/conditions.

There was no shortage of demand for today’s 10s simply because these CPI’s have been entirely superseded, also the case in 2008 outside of that period when the long end secondary market had succumbed to crisis illiquidity. Not only has “inflation” begun to show itself as transitory in 2021 like 2008 (and, to be perfectly clear, I’m not saying another 2008 is around the corner), there are all these same additional problems that first showed up thirteen years ago.

More than a decade plus unfixed, not even recognized.

To put this in today’s auction terms, if the CPI really does show what it seems to show, transitory, then the best of what little the global system has going for it right now (artificial US demand for largely goods) really is only for right now. The deflationary potential, which absolutely includes collateral scarcity (OTR, especially), has certainly amplified even higher that before.

This is true in the short run (versus reflationary yields which peaked almost five months ago back in March) as well as the structural long run trends unbroken by the Fed’s true status as something other than a central bank (it is, at best, a domestic bank authority and arguably an ineffective one here, too). Therefore, even though Treasury is totally out of control in terms of supply, and only getting worse, prices are higher compared to mid-March and obscenely higher compared to 2008 before supply issues really were put to the test.

Yes, deflationary potential is the only thing behind each and every single one of all these things. But, when you’re led (by everything, from your first day of school to every day in every internet article written up by the mainstream financial media) to believe the Fed is something it really is not, all is instead a confusing mess of seeming contradictions.

After all, the US CPI was just today pegged to be higher than 5% for the second month in a row while on the same day the benchmark 10-year yield fell to 1.34% in the secondary market, prices even better, much better, at today’s auction.

Stay In Touch