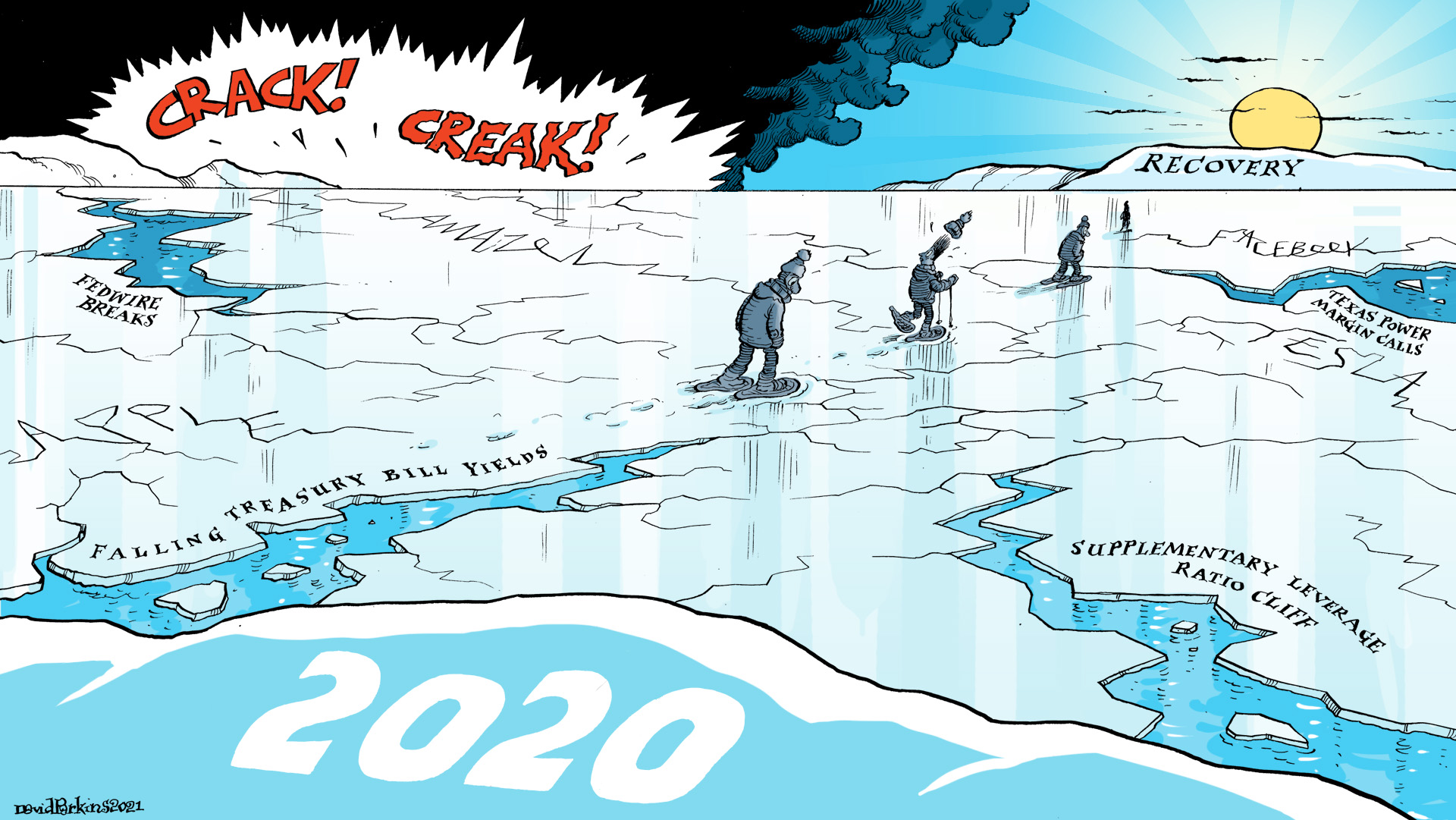

It was one of those little things that really shouldn’t have made any difference whatsoever, an interesting if trivial little nugget left behind for only obsessive scholars to care any about. Late in the morning of February 24, 2021, Fedwire shutdown. The fact a couple hours inactive snowballed into something bigger, we wondered if this would end up being indicative of how it might turn the world’s economic direction and then turn out.

Now six months later, we can quite confidently make our determination.

To get to recovery let alone some inflationary blowout, this would have required a monetary system beyond simple healing, one which globally must have been on the move in a way it hadn’t been in a very, very long time. Something meaningfully different; not bank reserves.

Getting blown offtrack by a tiny little nothing, an otherwise inconsequential nuisance, therefore transformed from trivial to monumental because this conclusively demonstrated, for the nth time, nothing other than bank reserves had actually changed.

I asked (myself) on March 25, only a month afterward, whether it really was just random coincidence:

In other words, problems in the “plumbing” (and we still don’t specifically know what really happened that day last month) aren’t by themselves game-changers; they’ve only become more likely to blow up into major issues since August 2007 because no matter what any Fed Chairman says they never provide the world with anything monetary; the only flood is illusion and, in Jay’s case, self-selected self-delusion.

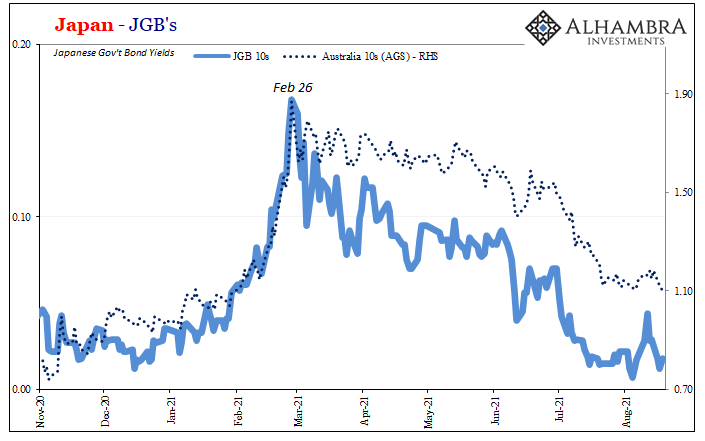

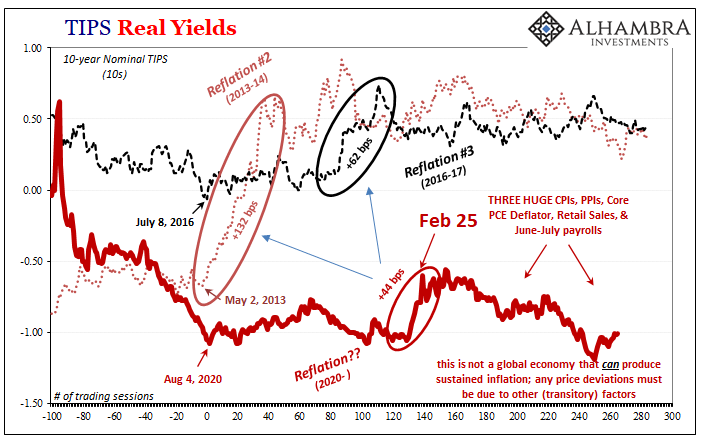

As of right now, without more information, Fedwire and the charts is coincidental. It is, however, more than enough to raise suspicion especially as, flood myth aside, more and more of 2018 (or 2014) creeps back into view.

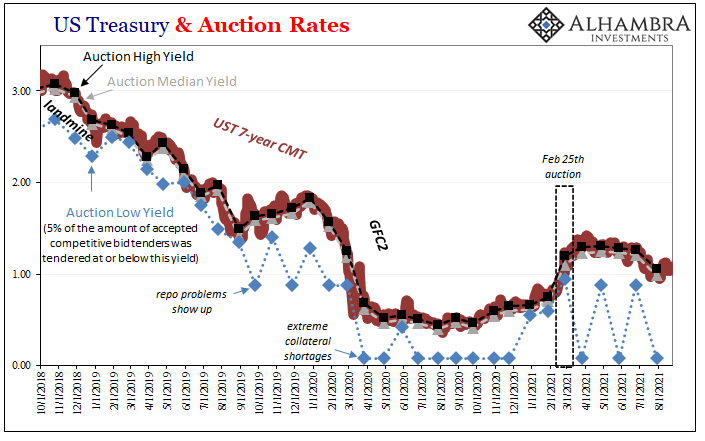

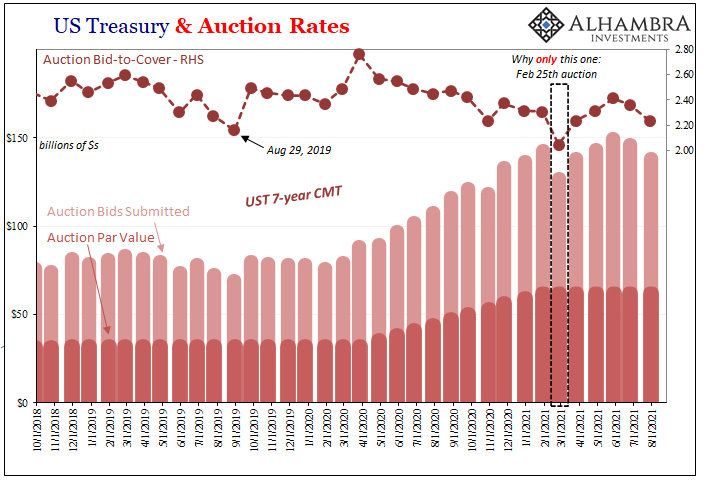

The sequence of events at the time might have appeared innocuous enough in isolation: Fedwire shuts down for a couple hours on the 24th; money dealers have to play catch up but get clogged up by uncleared transactions while they do; by the afternoon of the 25th, a 7-year note auction goes noticeably awry as distracted dealers are noticeable by their absence; the entire global money system is reminded of actual “liquidity” when something like this happens, as it does all-too-frequently in the post-2007 world where bank reserves are useful only in the sense of setting a fairy tale narrative.

Like September 2019 repo or August 2011 collateral, money gets real tight real fast without these dealer banks no matter what non-central central banks are doing.

It’s always the same word which comes up on these far too frequent opportunities: fragile. Jay Powell’s sleight of hand when it comes to the monetary and financial condition relies on his skills to mesmerize and dazzle the public (not the money system) with QE’s and LSAP’s, assisted by the financial press, a rapidly rising flood of bank reserves they together direct your mind to equate with useful money.

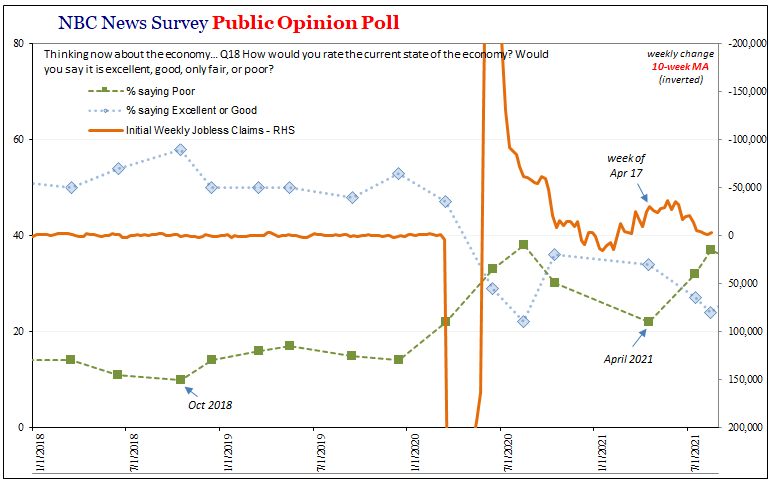

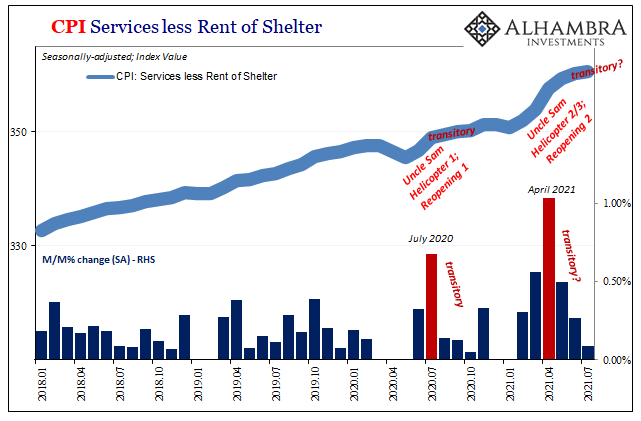

Put this together with a healing – even rapidly healing – economy in recovery, and it seemed the inarguable start of reflation becoming inflation.

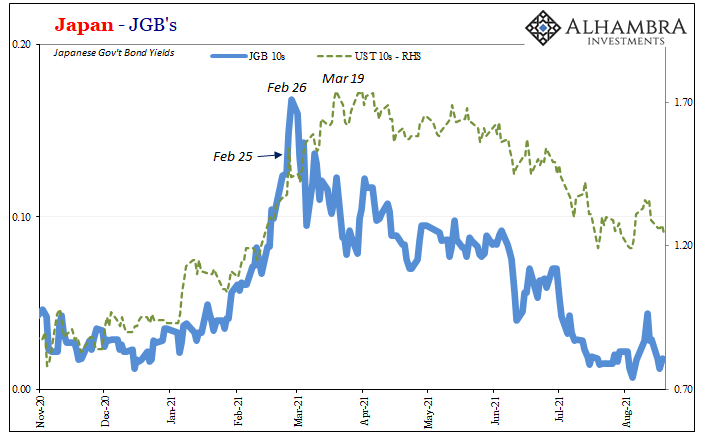

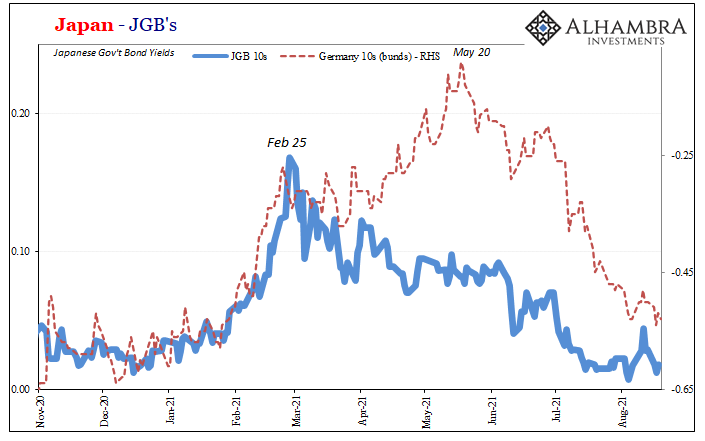

Yet, progressing a little more into 2021’s calendar, by May and three months later, still this jarring post-Fedwire contradiction:

The reflation-is-inflation story can’t account for anything here. Had Feb 25’s auction been the start of reflation-is-now-inflation, then the bond selloff would’ve accelerated, too. On the contrary, since the one auction on Feb 25 sticks out there must’ve been something else going on to explain why this continues to stand as the lone outlier.udely interrupt the mainstream monetary and economic fantasy by an obvious and serious break in trend dating back to what should have been a tiny little annoyance, combined with legit, rising concerns (spoken first in Chinese) about the real state of the rebound underlying all the artificiality of government influence, and then reinforced by the implications of that same monetary disruption, you can see why real markets (not stocks) would never have priced much inflation chance at any point.

Rudely interrupt the mainstream monetary and economic fantasy by an obvious and serious break in trend dating back to what should have been a tiny little annoyance, combined with legit, rising concerns (spoken first in Chinese) about the real state of the rebound underlying all the artificiality of government influence, and then reinforced by the implications of that same monetary disruption, you can see why real markets (not stocks) would never have priced much inflation chance at any point.

Including February 25.

The increasing number of months where these few days remain relevant on all these charts answers these questions with greater confidence, if in the wrong way. From April:

Instead, it’s another pertinent example from another key market which blatantly switched out of reflation and into some weird sort of pause in it. Maybe it progresses and eventually forms a more complete inflection, maybe reflation restarts at some point. For now, it is a globally synchronized short run problem.

Why a problem?

Because during this same almost two months, that has been when everything has been supposedly going right; not just right, darn near perfect. You don’t need me to recite the list yet again, vaccines et al.

As noted earlier today, April and May really do seem to show up in a lot of data for all these wrong reasons, meaning their turn having been anticipated by the anti-reflation in global bonds which relate meaningfully to the proliferation of chart-breaking begun on Feb 24-25.

For all the angst about COVID delta (2021’s “trade wars”), the real mutated strain of the actual deflationary disease plaguing the global economy was called Fedwire. One month after it, we asked if what had followed was just coincidence fearing, as always, our own confirmation bias. A few months further, more fell into its vortex than easily skipped away.

Today now six months after we can safely conclude, no, it was neither bias nor could it have been mere coincidence.

And that means a lot more than you might think. Flood of bank reserves don’t fix broken money, and that leads nowhere good. How appropriate given Fedwire began as a little nothing and has turned out to be a lot of something. The same sick something as always. That is the problem, and the answer.

Stay In Touch