One reason why I still believe the US most likely would have entered a recession at some point in 2020 even without COVID wasn’t just the yield curve inversion that popped up several months before then. In August of 2019, the small part of the Treasury curve most people pay attention to (2s10s) did send out that dreaded signal, suggesting already to expect contraction in the intermediate term ahead of then.

But there was more to it than that, much moving in the same way, the same idea and general fear being picked up in real economic data, too, consistent with those upside down calendar spreads (other parts of the yield curve had inverted months before).

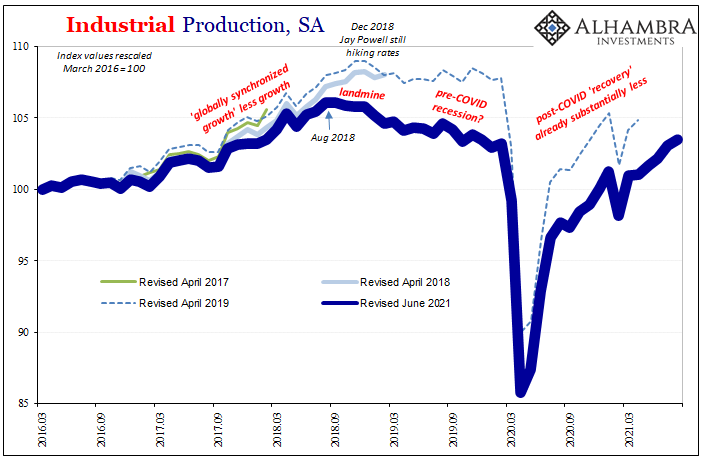

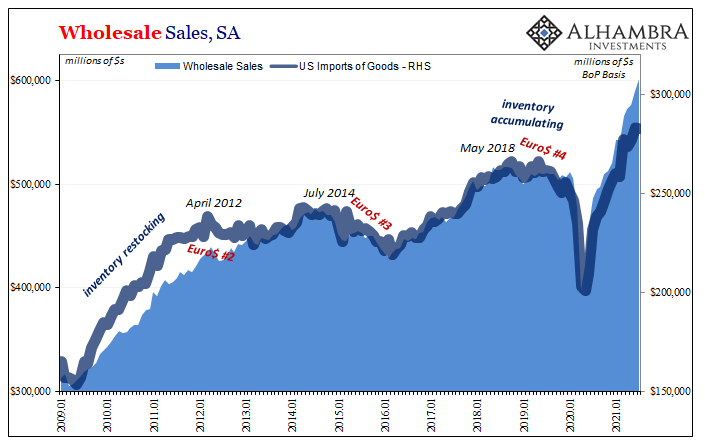

There had been serious weakness around the rest of the world (Euro$ #4) which was only catching up to the US economy despite the falling, 50-year low unemployment rate. After all, Jay Powell had ended 2018 with a rate hike but then by the middle of 2019 it was suddenly rate cuts. In other words, even the perpetually optimistic inflation-ists at the Federal Reserve could no longer deny that very weakness like they had all throughout the year prior.

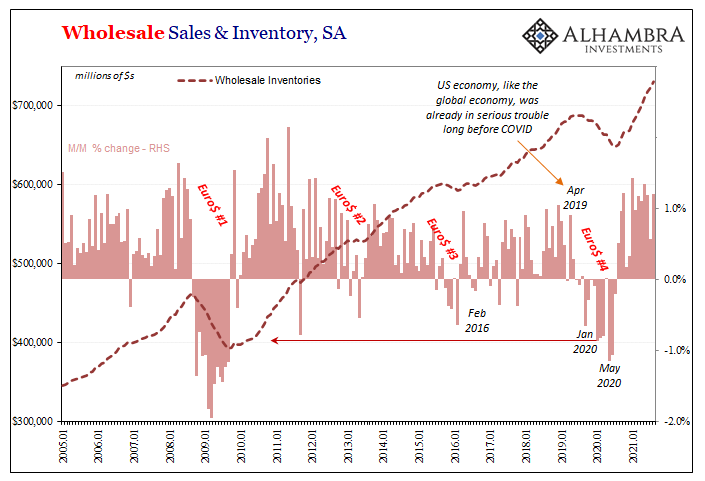

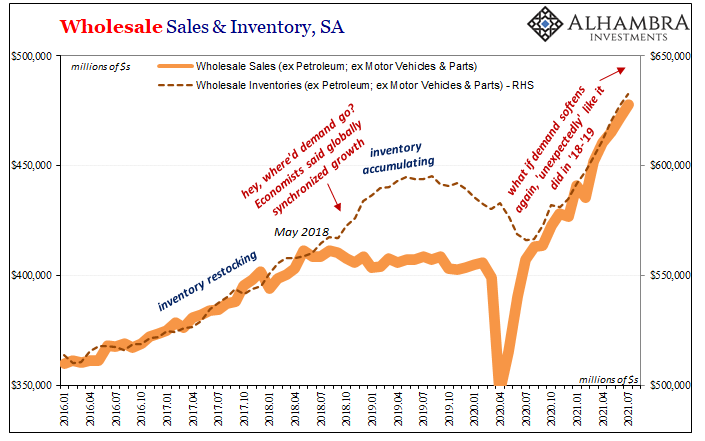

Those rate cuts, the first of eventually three begun at the end of July 2019, were about “confidence.” It hadn’t just been Treasury market traders on alert. There was a serious inventory problem, a dangerous buildup which had been building since the middle of the year before getting more and more out of balance; therefore, the goods economy in pre-recession shape at the very same time the yield curve sent out its own warning.

In early August 2019, I wrote:

Monetary policy, the modern money-less variety, seeks to insinuate itself into that circle before it becomes self-reinforcing. Maybe if wholesalers aren’t so negative when retailers call a halt to the flow of goods up the supply chain that wholesalers don’t make that call to the producers. Get them optimistic about the future (with rate cuts!) and perhaps they hang on just long enough for sales to return to trend and retailers start buying in bulk again.

This is certainly one context which explains the recent rate cut from the Fed. Even if you and they believe the US economy is otherwise strong or even very strong, no one can deny what has been happening on the wholesale level.

In truth, Jay Powell panicked because globally synchronized growth had already turned into a globally synchronized downturn late in 2018 (landmine) and did so unambiguously. With key parts (Germany, Japan) of the worldwide system experiencing outright recession during that middle of 2019, what may have awaited the FOMC to begin 2020 was the very real prospect for further resynchronizing with Germany and Japan’s contraction.

The inventory situation right then had announced the nearly perfect set of circumstances for just that possibility.

The vicious part of the inventory cycle had already begun by the time the first rate cut was announced, with wholesalers, in particular, calling a halt to the production and general supply chain trend.

We will simply never know if it actually would’ve gone that far, as presumed by the yield curve and illustrated by the inventory and sales data (and softening figures in other accounts, including retail sales to end that year). COVID showed up and the pre-recessionary condition in the US, along with actual recessions outside the country, were quickly and easily forgotten by the public.

The inventory condition now in 2021, as discussed last week, seems to be in a very different way. Given the logistical nightmares which have engulfed much of the US supply chain, in a JIT environment there was simply no margin for error in order to be able to absorb such large twists to it, the current inventory cycle is still just as uncertain as it had been two years ago:

It may be a different look to the cycle, though not necessarily an entirely different outcome. Suppose retailers (outside of automobiles) grow concerned about supply availability or shipping times. They might naturally react by boosting their current order flow if only to increase their chances some product makes it through the clogged shipping channels.

As that increased order flow unrelated to demand continues to move back through the supply chain, it probably would only make the transportation issues that much worse. It’s already a mess, and because it’s already a mess the entire supply chain tries to stuff more goods through it rather than less, rather than giving the system some time and space to work out enough kinks.

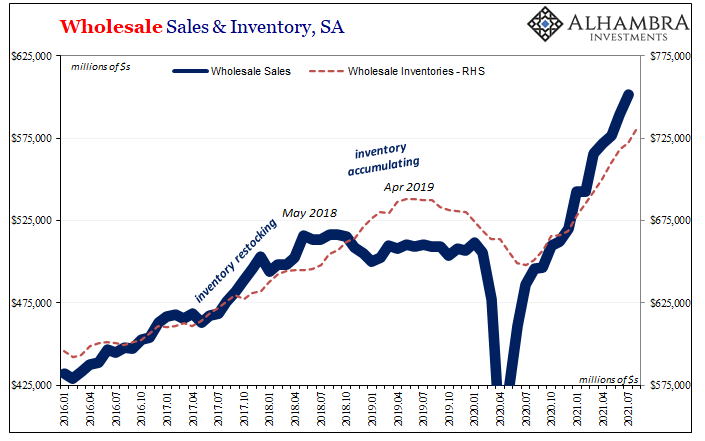

In terms of wholesale sales and inventory, right now the situation appears to be quite neatly balanced or better. Sales have expanded at a much faster pace than inventory has, meaning that retailers are still in huge demand for goods.

However, while this may be the case overall, there are two wholesale segments which are skewing the data: the first is the auto business.

Wholesale vehicle inventories are, like retail dealer inventories, incredibly, historically low. It does seem as if the mainstream view of the inventory situation is colored too much by this one segment (leaving people to think the entire economy is suffering from a huge lack of inventory).

Adjusting for it, the rest of the wholesale level of the supply chain is, on the contrary, taking in a ton of new goods; more of them all the time:

It’s just that sales have continuously outpaced the upward flow of products.

Again, this seems no problem whatsoever since sales have exploded at a much faster rate than even rapidly rising inventories, meaning that wholesalers appear to have for themselves quite a cushion to cushion any expected drop to the goods frenzy over the coming weeks and months (as the effects of Uncle Sam’s helicopter further fade and the unemployment “cliff” takes out another leg under artificial consumer demand).

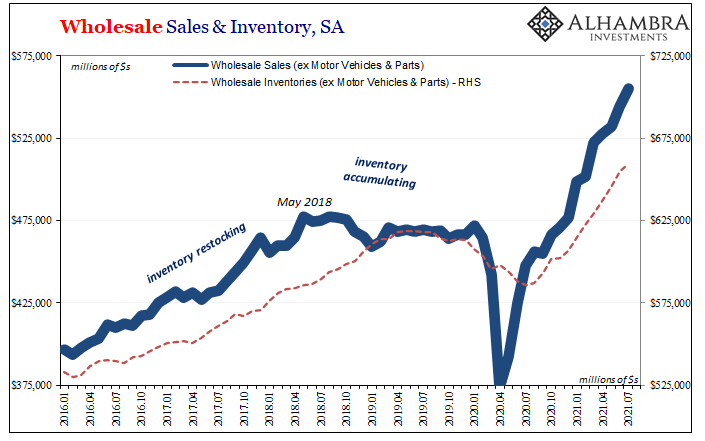

But the other skew in the wholesale data, at least, is due to the energy sector, specifically petroleum. When you adjust for that along with motor vehicles suddenly the inventory situation for the vast majority of everything else in the good economy looks quite different:

For everyone else in that goods economy – at the key wholesale level – inventory has been at least keeping pace with elevated sales. And, as noted last week, this doesn’t count who knows how much is in the process of being transported, clogged up sitting on container ships or stuck in the various railroad snafus.

In other words, outside of oil and autos, there’s probably even more inventory than what’s already figured here.

Retailers, in particular, some of the bigger firms have claimed they are ready for what will be a delivery rush creating some degree of overhang. But as we saw in 2019, it doesn’t really take all that much “unexpected” softening in demand to kick the whole goods economy out of the virtuous part of the inventory circle and into its more vicious twin.

The wholesale data outside of autos and oil indicates there may not be as much cushion should the overhang get to be larger than expected once consumer/retailer demand normalizes perhaps much quicker than is currently planned (see: fast pace of downward revisions to Q3 GDP estimates).

And this isn’t just a potentially negative future factor for domestic wholesalers and US producers. Unless demand can remain as elevated as it has been, consumers buying the crap out of everything they find in front of them (often in lieu of previously “forbidden” services), this would potentially transmit the downside of the inventory cycle overseas, too:

The inventory potential/situation is not, overall, like what’s going on specifically in the auto sector (or petroleum). Wholesalers have been ordering, and receiving, an enormous amount of product already. And, again, that doesn’t count what’s literally floating around in containers no one can really track.

Government Economists were more than OK with all this because they believe, and probably still do right now, such artificial “stimulus” would create a positive “multiplier” greater than one. In other words, this overheating to the goods economy would go on and on for quite some time more.

Many corporate CEO’s are saying they think so, too.

Then again, CEO’s like central bankers are advised by Economists (which is why they keep making these same mistakes over and over).

Whatever you make of the unemployment rate, it is, essentially, a lagging indicator. Like the bond market and the yield curve, the inventory situation is most often forward-looking. Powell and the Fed are tapering on the advice of the former, ignoring the potential of the latter in pretty much the same way as a few years ago.

Stay In Touch