Is it delta COVID? Or the widely reported labor shortage? Something has created a soft patch in the presumed indestructible US economy still hopped up on Uncle Sam’s deposits made earlier in the year. And yet, there’s a nagging feeling over how this time, like all previous times, just might be too good to be true, too.

To start with, the rebound from last year’s recession is decidedly, maybe even uniquely uneven. Not just explosive goods sector vs. moribund services, there’s also a divide between bigger businesses and small (what are left of them), and then finally, most importantly, truly vast differences the US goods sector from practically everywhere else in the world.

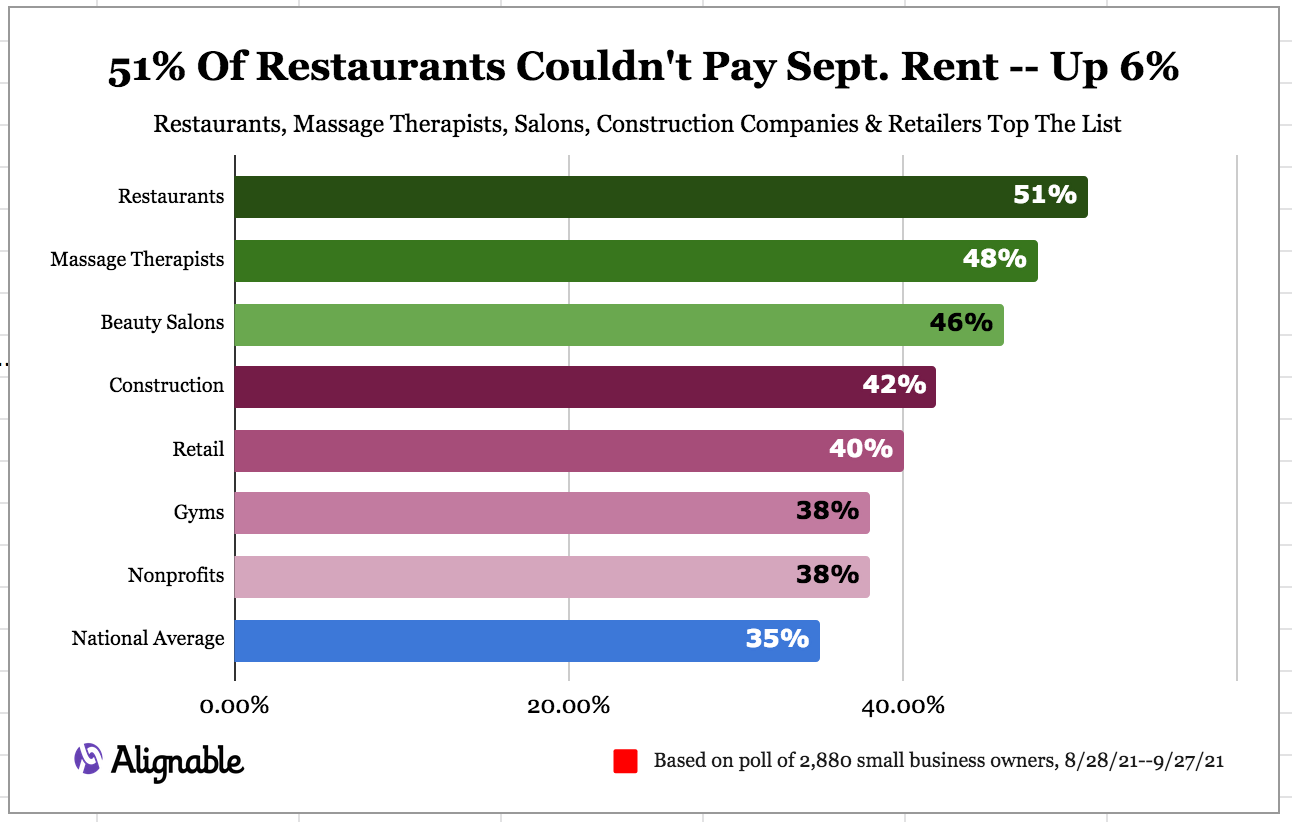

Taking account of the first two of those, recent polling data from Alignable came up with this:

In September, 35% of small businesses in the U.S. (up 5%) and 38% in Canada (up 6%), couldn’t pay their rent. Many cited the surge in Delta variant cases, as a leading reason for the issue, along with skyrocketing inflation, and an ongoing labor shortage.

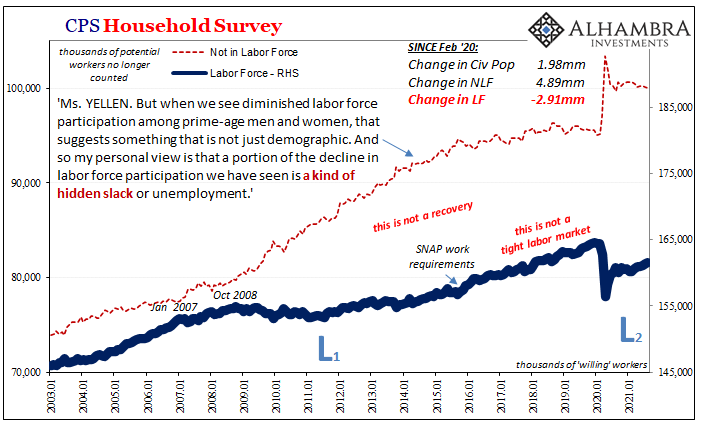

Apart from the obligatory pandemic reference, doesn’t the first part of that data actually explain the last rather than the other way around? In other words, though these 35% (and more) may blame their struggles in part on this labor shortage we constantly keep hearing about, wouldn’t the fact so many can’t meet (and so many more probably barely able to meet) their basic rent obligations actually be the “labor shortage?”

If you can’t even pay rent, you aren’t coming anywhere close to paying a market clearing wage. On the contrary, you’ve one foot in bankruptcy. And when you aren’t able to scratch together the basics, workers aren’t going to be lining up at your door even if you don’t quite see it that way (because that’s not how the Wall Street Journal always describes Jay Powell’s taper-take on the US economic situation).

Thus, the “labor shortage” isn’t about a shortfall in the number of workers, it is a wholly separate kind of deficiency where companies, skewed away from the biggest ones, are experiencing an economy shortage.

Deeper issues beyond delta COVID may account for the perhaps emerging softness. There is a world of macroeconomic difference between an alleged labor shortage (good thing) and what we keep finding time and again (see: 2018); month after month.

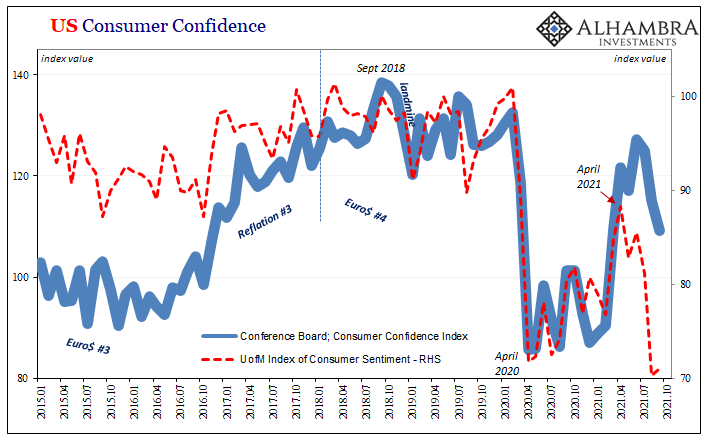

To that end, the Conference Board announced yesterday another sharp drop in its consumer confidence index. For the month of September 2021, the headline number was 109.3, down from a revised 115.2 in August (and 125.1 for July). Analysts were thinking there would be a small rebound in this measure, to 114.5, as during the month the delta variant’s spread dissipated and with it the current fear-load over caseloads.

This may still happen over the months ahead, though at best delayed beyond into Q4.

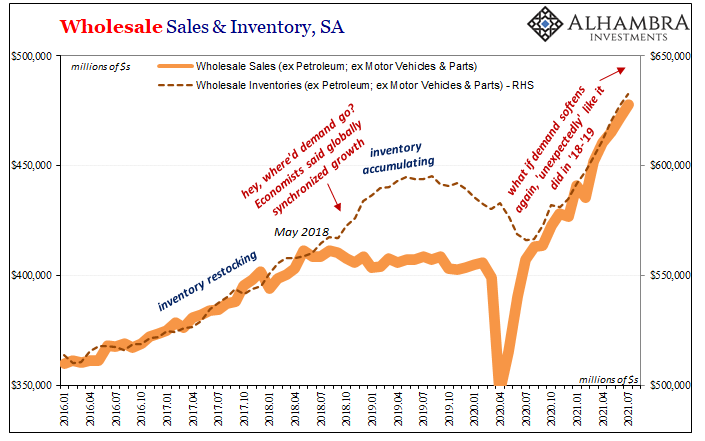

Yet, there is also a new potential problem maybe just now coming into view, too: the possible downside to the inventory cycle we’ve been talking about over the past week.

It may be a different look to the cycle, though not necessarily an entirely different outcome. Suppose retailers (outside of automobiles) grow concerned about supply availability or shipping times. They might naturally react by boosting their current order flow if only to increase their chances some product makes it through the clogged shipping channels.

As that increased order flow unrelated to demand continues to move back through the supply chain, it probably would only make the transportation issues that much worse. It’s already a mess, and because it’s already a mess the entire supply chain tries to stuff more goods through it rather than less, rather than giving the system some time and space to work out enough kinks.

Quite simply, there is the potential – should softening demand stay “too” soft – that all that future inventory delivery begins to weigh on present day production levels. This is the classic business cycle as derived historically from inventory excesses.

Should this begin to take place, we’d very much expect first new orders at manufacturers to slow and then contract on down the supply chain, as the upper levels of that chain begin to reassess the flow of goods already in process (either being produced or, given the logistical problems, produced and in-route) in the wake of changing conditions (or trends not working out as anticipated).

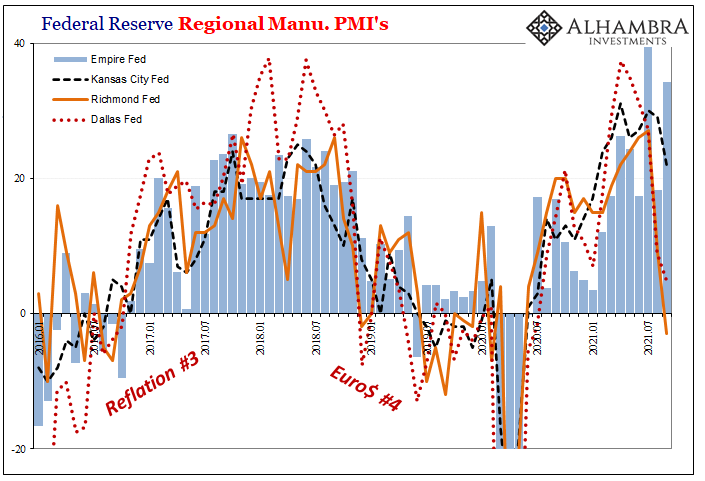

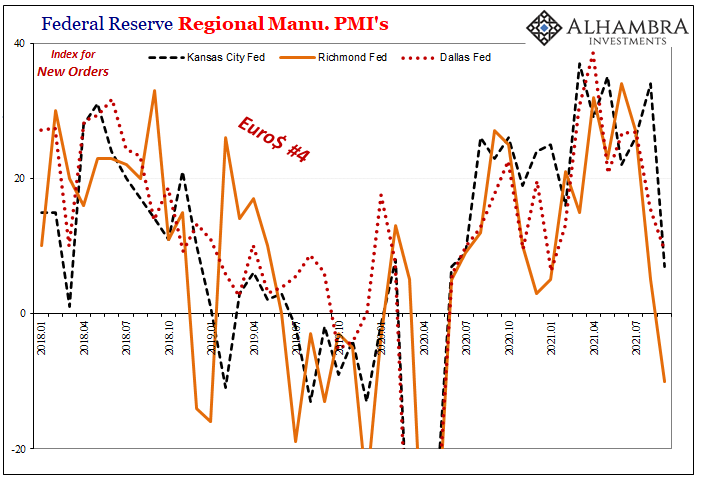

Looking around and digging though second tier data like the various Federal Reserve regional manufacturing surveys, yes, there is already the growing hint of problems in this way. Several of them, notably Richmond’s index (-3) update also from yesterday, have similarly tanked recently.

The delta coronarvirus variant, as always, is immediately singled out for excusing the softening. Yet, it’s actually the new orders indices (second chart below) under their headlines which grab our attention:

For the Fed’s Fifth District in Virginia, the new orders index was a meaningful -10 in September – which equals its 2018 landmine depth (as do the other two this month if still on the plus side).

It is way, way too early to draw any kind of hard conclusions about anything. This really could just be the uncertainty of the latest pandemic wave. These could also be nothing more than idiosyncratic factors plaguing specifically these three particular regions (though that’s less likely, which is why I included the three of them); other regional Fed surveys haven’t come down nearly as much as those above.

There is, however, the uncomfortably reasonable possibility of a looming inventory cycle combined with the fading influence of “stimulus” plus finally the real setbacks of the “labor shortage” – both the ongoing and rising pain felt by small and medium businesses which then leaves far too many workers unable to actually find worthwhile work at meaningful pay – creating an increasingly less recovery-like rebound as 2021 draws closer to its close.

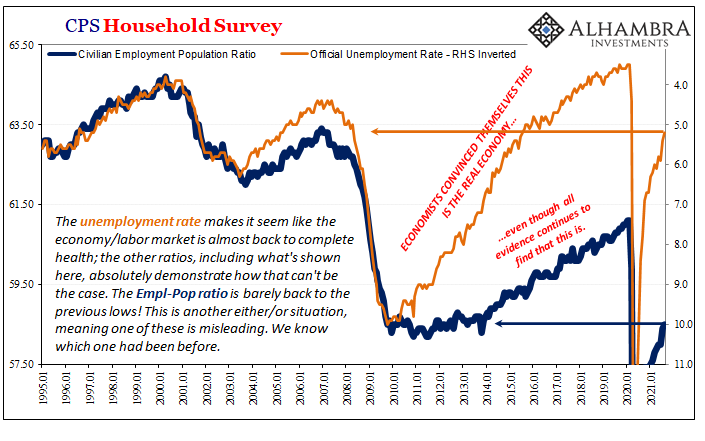

Whatever you make of the unemployment rate, it is, essentially, a lagging indicator. Like the bond market and the yield curve, the inventory situation is most often forward-looking. Powell and the Fed are tapering on the advice of the former, ignoring the potential of the latter in pretty much the same way as a few years ago.

Not only is this too familiar, and how it can’t be ruled out, the more months pass the more familiar it all becomes and the less we are able to disprove all this macro downside potential.

Stay In Touch