Spend even a modest amount of time on the subject, and the distinct impression you are left with is that American ports and railyards are dealing with a truly epic jam because the economy has been so good there’s just too many goods for anyone to reasonably handle. Juiced by the federal government’s helicopters, Americans spent, spent some more, and then went back to their computers and gave Amazon – therefore overseas producers – even more of that borrowed Uncle Sam cash.

At the very same time, our poor supply chain already stretched by this unique frenzy was concurrently walloped by a labor shortage which, we’re also told, has been produced by the same generous government handouts (lazy Americans).

It’s just too much to handle all at once, and now these overloaded, under-layered logistics are holding back the overall economy which could be even more awesome if shippers and handlers ever got their act together. As red hot as Warren Buffett says it is right now, inflationary inferno hot, it could be even hotter if not for unnatural interference.

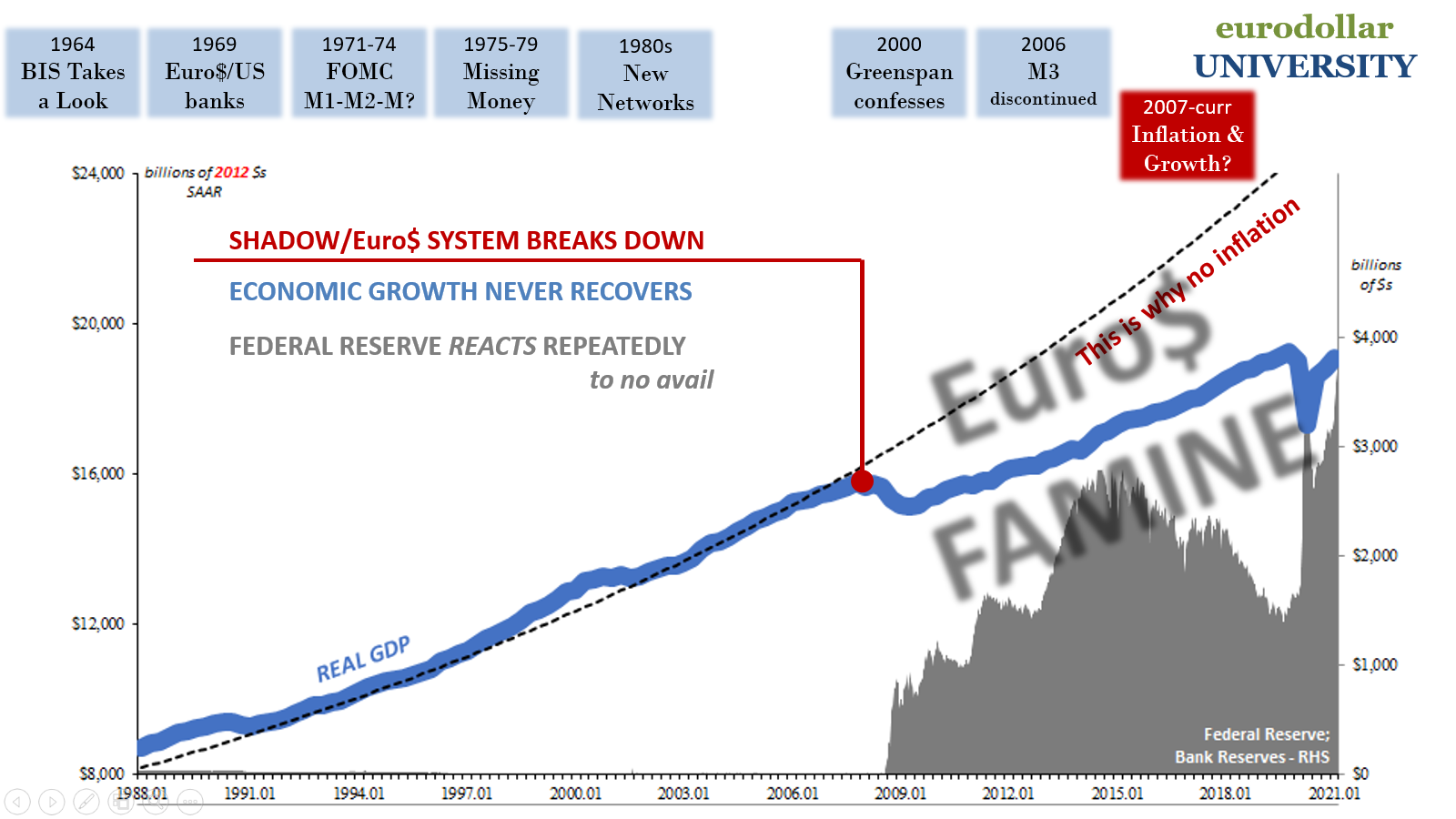

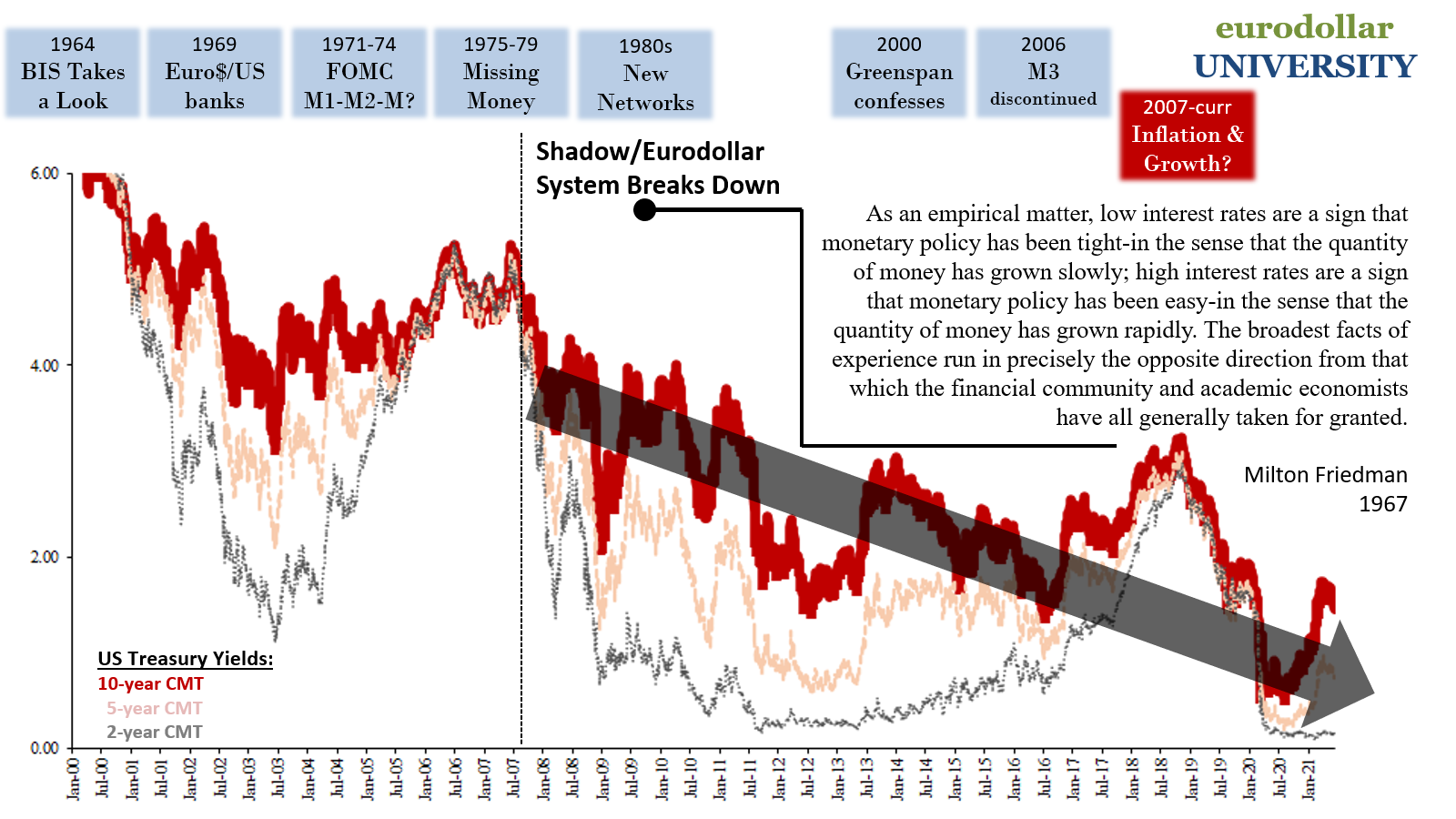

That’s the narrative, anyway, and like all the prior attempts at it, these seek only a single aim: to convince the public of some high level for inflation potential. Each time, too, the basis for it is “money printing” and an economy claimed to be on the very cusp of overheating.

Neither of those have been true to date, so it should be fair to ask if this time is actually different (as well as demand some reasonable explanation as to why it wasn’t all those prior). A good place to start is actually at the nation’s ports because that’s where so much attention has been focused. Between shipping and container rates, you’d be forgiven for thinking that these crucial trade network nodes are clogged up with goods on the move – rather than empty containers with nowhere to go.

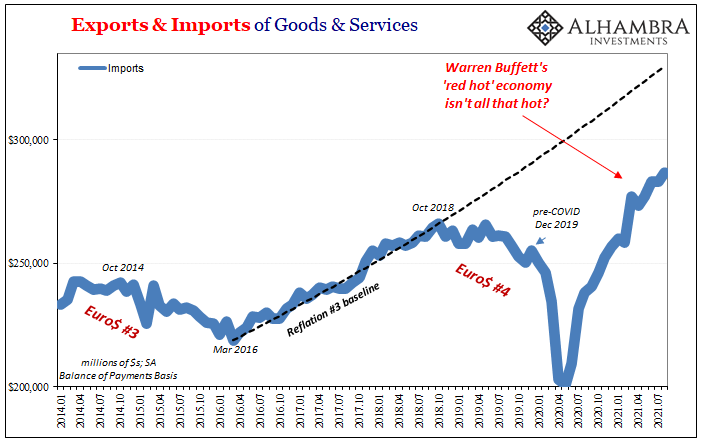

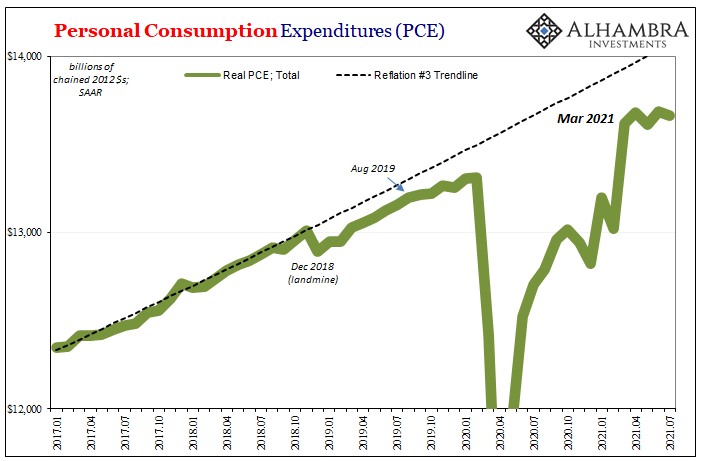

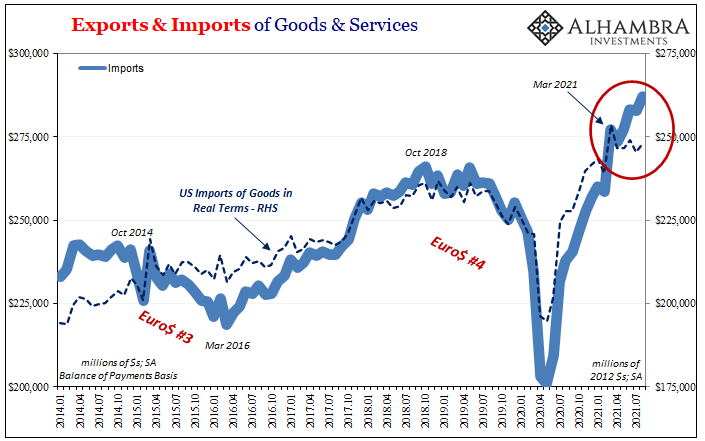

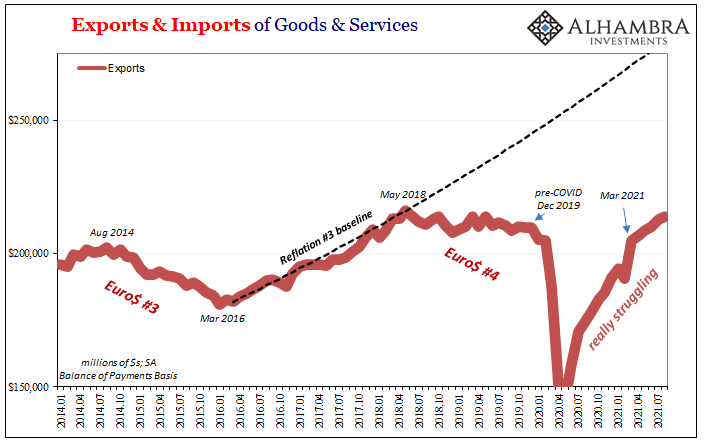

There certainly had been a consumer-led splurge in goods and therefore the trade of goods, but “splurge” lacks important context. If it is simply a rebound from the depths of a truly awful prior year, that’s something different – categorically. And as a rebound even goosed by government “stimulus” which still falls well short of recovery, then the situation remains firmly on the wrong side of “overheating.”

In other words, by all (data) accounts congestion is more a product of the imbalance between demand and supply rebound speed (including the supply of shipping capacity) than anything like “red hot.”

And these were considerable questions even before this past March.

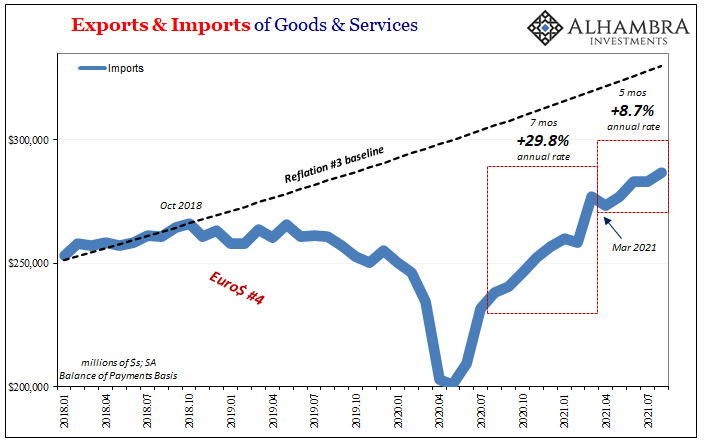

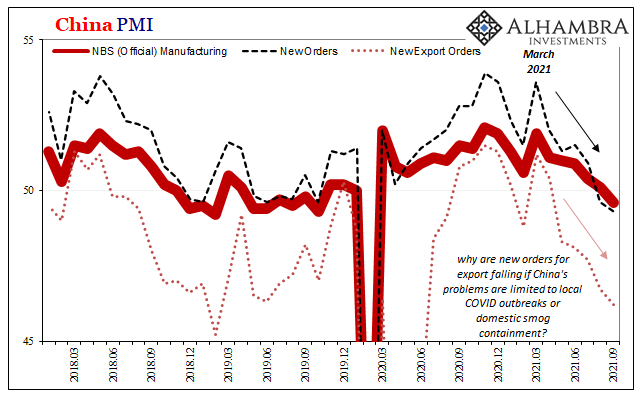

Over the last five months (the latest trade data from the Census Bureau updates August 2021) beginning in April (there’s that month again), import growth has severely decelerated. Some might claim this is merely the predictable result of this same overburdened trade system becoming only more overburdened, yet this slowdown as well as its timing are well-documented in an abundance of data that have nothing to do with railroads and any shortage of truck chassis.

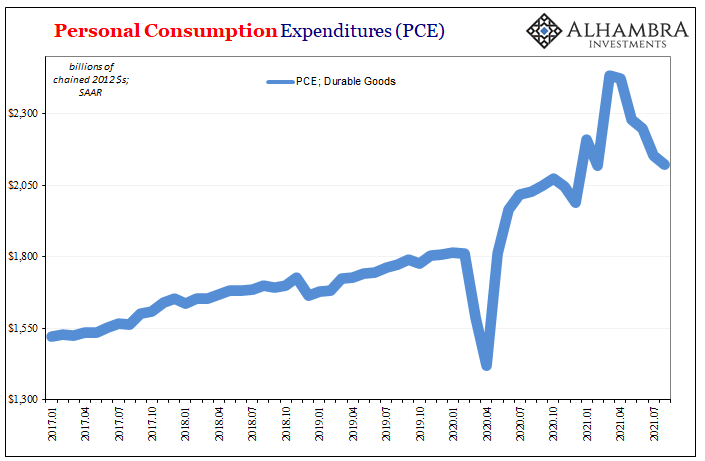

Starting with consumer spending, including what’s been outlaid for especially durable goods:

If we then put US goods imports in real terms, as Census does, the difference in interpretation is even more dubious; in 2012 dollars, import volume appears to have declined rather noticeably during this same April to August period in question.

Even if it hasn’t outright dropped, deflating into “real” terms is always tricky and may never be so precise, there sure hasn’t been any sort of massive and overflowing demand from the US even as consumers really had been awash in helicopter funds. The situation really has slowed to a substantial extent.

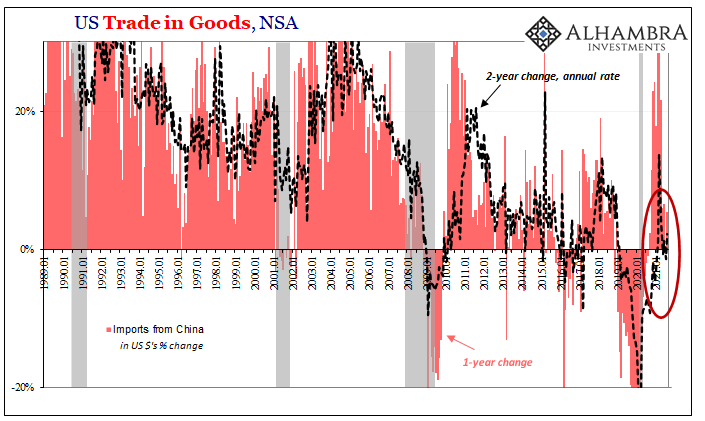

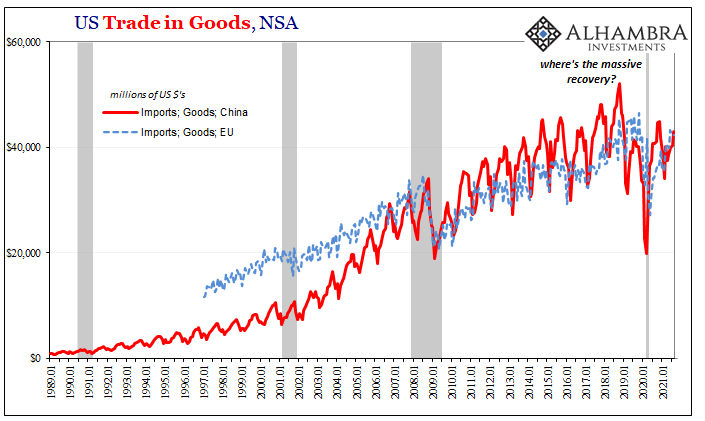

You only have to go through the various country accounts, in goods, to see that at best what transpired earlier in the year was how trade rebounded to levels much better than last year (an incredibly low standard). The change from truly bad to less bad came about at high speed thanks to Uncle Sam, with the speed creating the impression of an actual recovery (extrapolated, as always, in a straight line).

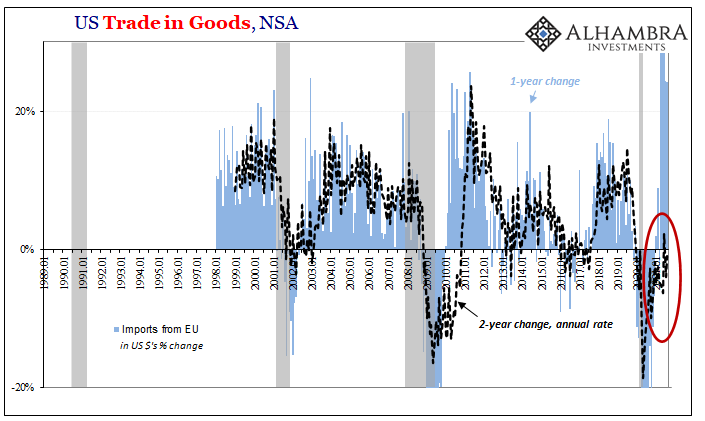

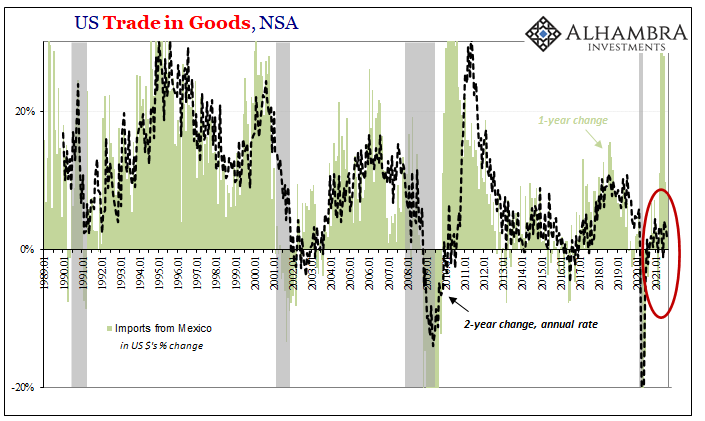

By no means has trade to our biggest trading partners recovered, nor does it look very likely it will any time soon. The Chinese, most of all, have to be just baffled (not really, they know the game that’s being played here) about this “red hot” economy nonsense and how it is just taken at face value. Along with Europe and Mexico, US imports from all three aren’t even close to 2018 peaks.

Since annual rates are all skewed by base effects, the 2-year changes really show where trade levels truly stand.

It’s even worse around the rest of the world; one reason why so many empty containers are piled up and clogging up certain domestic port facilities is that US producers just haven’t been needed to produce much for outbound trade. Global demand for American products, a useful proxy of overall global economic conditions outside, well, it’s still unbelievably (unnecessarily?) ugly.

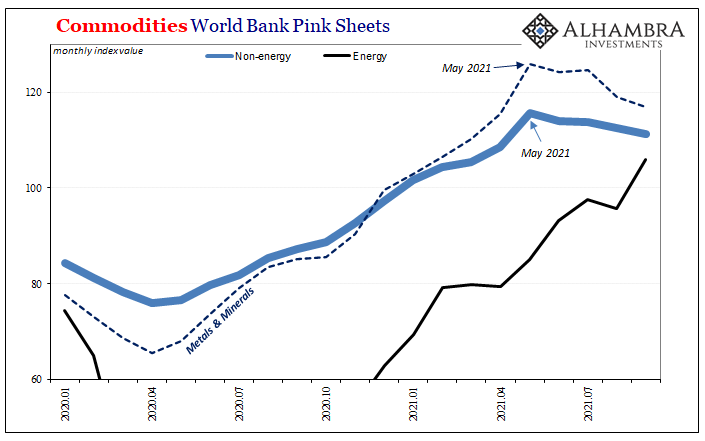

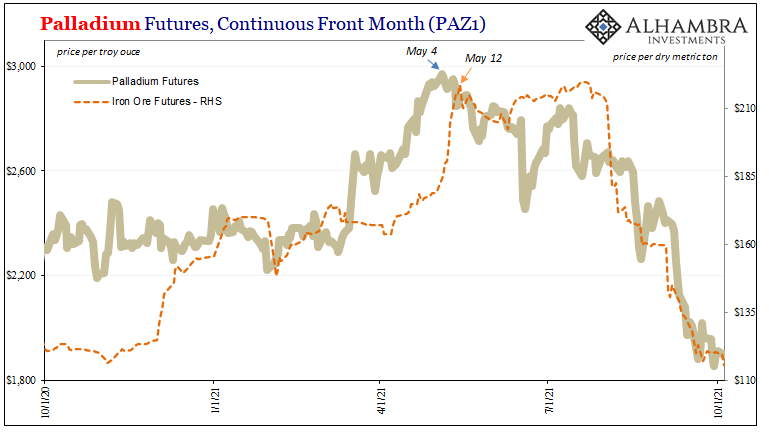

Not only is it nowhere close to recovery, like we find in US imports there had been a material slowdown dating back to, once again, March and April. Might prices of certain types of commodities be onto something here where it comes to global demand potential?

It’s not like America was overrun by so many goods the supply chain couldn’t handle; on the contrary, demand began to rebound if somewhat faster than diminished trade capacities which couldn’t keep up even at these relatively (to 2018, which wasn’t a great year, either) lower trade volumes and values.

Supply shock. Prices naturally adjusted to it. We’ve seen it before, and it is lack of demand which always ends up being the long run problem.

The need to feed the inflationary narrative, however, this is what took small “e” economics and turned it into Capital “E” Economics desperate for any kind of success. The mainstream desire for an inflationary outcome, the very same as expressed hysterically in 2018 (and to an extent in 2014), yet again led to the overhyping of specific factors; more mountains from molehills.

The supply chain issues in 2021 may happen to be, or have been, among the largest of molehills the US economy has come across since August 2007, yet in type it isn’t actually any different. The public is again being misled into believing a rebound, or just the direction up, is all it takes.

That was the world’s big problem before April; since, it’s a matter of how slow this repeated and repeatedly predictable slowing will go. Two-thirds of the way through 2021, despite the usual assurances based on the unusual small “e” economics of current day shipping problems, there’s far more to question about demand now than supply.

It really is the same thing over and over and over (and over and over).

Stay In Touch