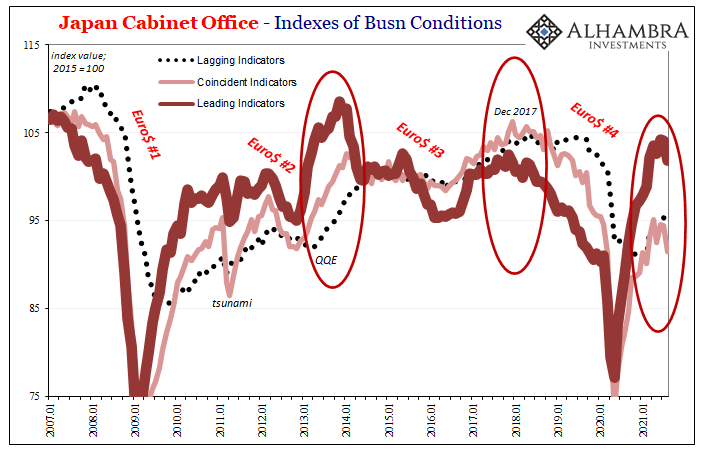

With so little to like about Japan’s own economy, the Japanese long ago had come to count on putting their money and their efforts elsewhere. General fortune has therefore become a product of eurodollar fickleness; reflation in the global monetary system “allows” Japan a bit of additional breathing room. The economy picks up and confuses central bankers and Economists alike into thinking recovery and inflation.

Happens over and over, country after country.

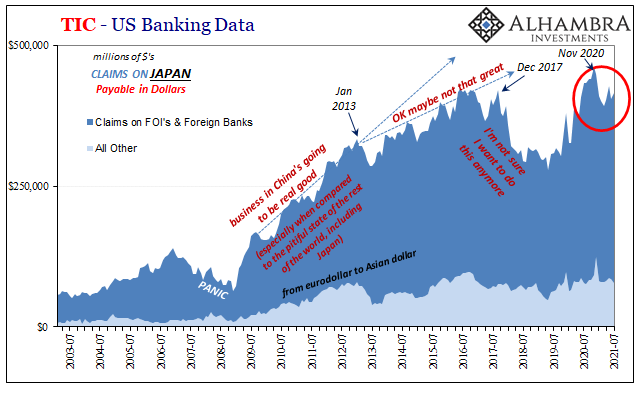

Japan was almost a perfect indication for when Reflation #3 started to buckle and then fail back in late 2017 and early 2018. Monetarily, eurodollar-wise, the Japanese ran for the exits leaving the rest of the world exposed (and emerging markets to exclaim “dollar funding has evaporated” without being able to point to its actual cause).

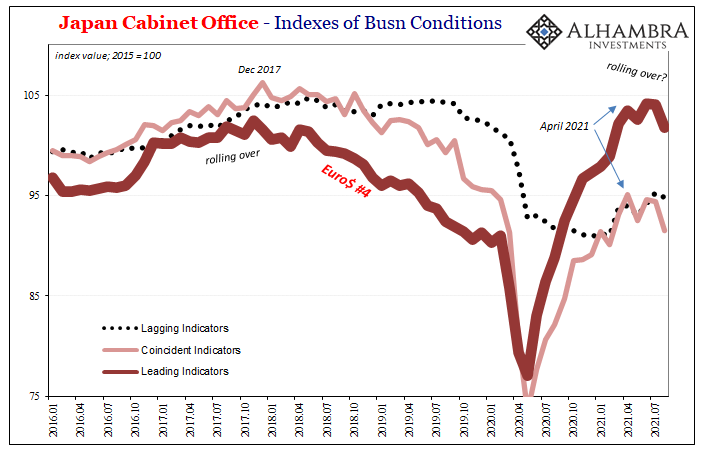

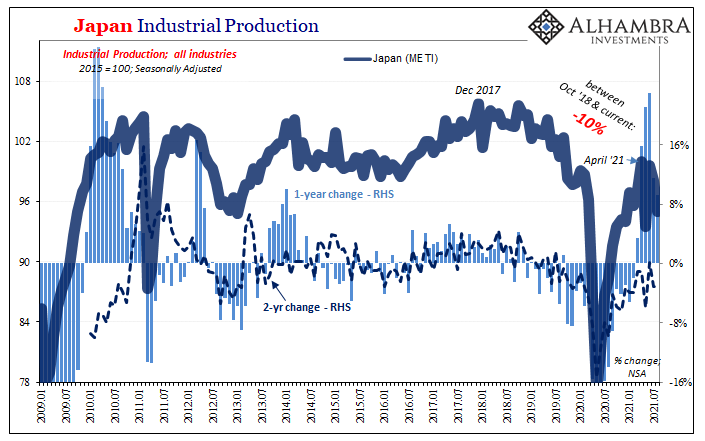

In pure economic terms, like Germany, the export-heavy orientation in Japan was a leading indicator for Euro$ #4 wrecking globally synchronized growth, quickly turning it into a downturn instead which eventually globally re-synchronized in the wrong direction. Industry behind Japan Inc. was one of the first places to display the rolling over.

Are we seeing history repeat again?

As more months go by and the data refuses to improve, and in some cases gets worse, we’re left with fewer alternative explanations. One is, of course, delta COVID. And Japan has been hit plenty by this latest of the pandemic. Just last month, emergency government restrictions were extended yet again (though these are nothing like lockdown-type constraints).

That alone cannot explanation why only this latest “wave” of the pandemic would account for a very different turn in the Japanese economy. After all:

Japan has been struggling with a fifth wave of the virus and last month extended its long-running curbs until Sept. 12 to cover about 80% of its population. [emphasis added]

Wave #1, obviously, the big contraction but then throughout Waves 2 to 4 Japan like elsewhere around the world was unbothered economically. The economy appeared to be rebounding no matter how many additional bursts of rising case counts. It was only until April – that same month again – when suddenly the Japanese economy, coincident to much if not most of the rest of the global economy, that’s when it began to change.

If this was COVID, why did it take until the fifth wave before making any further difference? In reality, the turn may have started before the fifth wave.

In terms of Industrial Production, seasonally-adjusted the peak was, yet again, April and it has been lower ever since. From the Japanese Cabinet Office, its coincident indicator for the entire Japanese economy likewise topped out in the same month as IP as would the leading indicator (though it managed a slightly higher result in June). Either way, something clearly changed for Japan back around April.

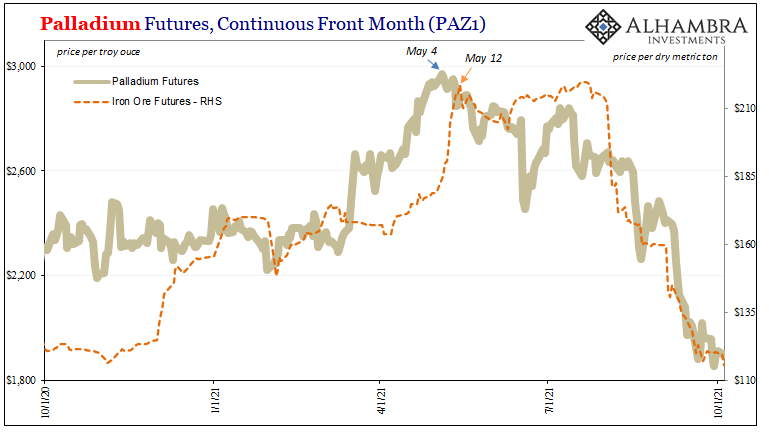

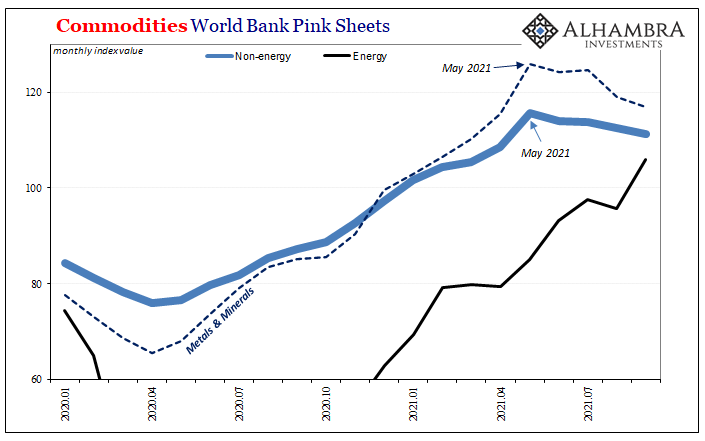

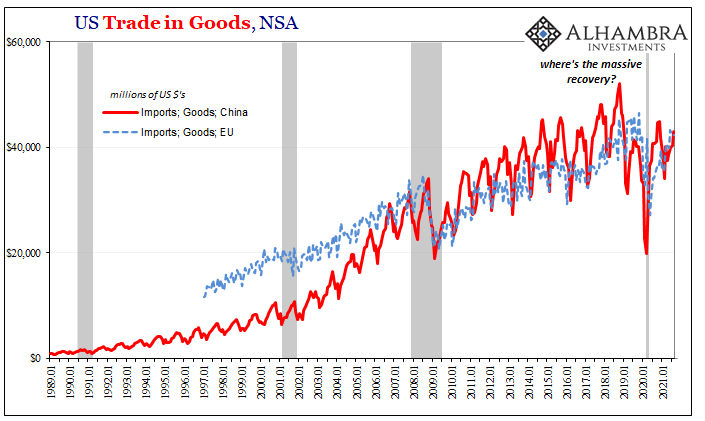

But it’s not just Japan, is it? Worldwide, April and May continually show up at the very least like short run inflections that have now extended through summer and by some measures now into autumn (like commodity prices and that perplexing increase in the dollar’s exchange value).

Even the Economist, a magazine dedicated to the thorough cheerleading for, well, mainstream Economics, even they are struggling to get a handle on what all this appears to indicate. In the latest issue, as Emil Kalinowski hits me with on our last podcast (next week), the mainstream can’t help but notice:

So far this year economic growth across much of the world has been robust and unemployment rates, though generally still above pre-pandemic levels, have fallen. But the recovery seems to be losing momentum, fueling fears of stagnation.

Of course, they still foresee more “inflation” because their orthodox worldview is inseparable from the central bank-centered monetary model. So, they predicted recovery and inflation but are now beginning to realize maybe not the first part.

The Economist considers this as higher potential for “stagflation”, a term popularized during and about the Great Inflation of the 1970’s. It also made a comeback around 2010 and 2011 – not that anyone remembers now. Quite simply, without the money for inflation what’s left is just the stagnation; which very succinctly and accurately describes the decade which followed 2010 and 2011.

Is this time really different? So far, the stagnation is proceeding almost as if right on schedule; the non-central bank schedule.

No need to call it stag-deflation because that’s just redundant. In other words, as the renewal of stagnation grows larger on the horizon, settling the label’s other half is already being taken care of.

Stay In Touch