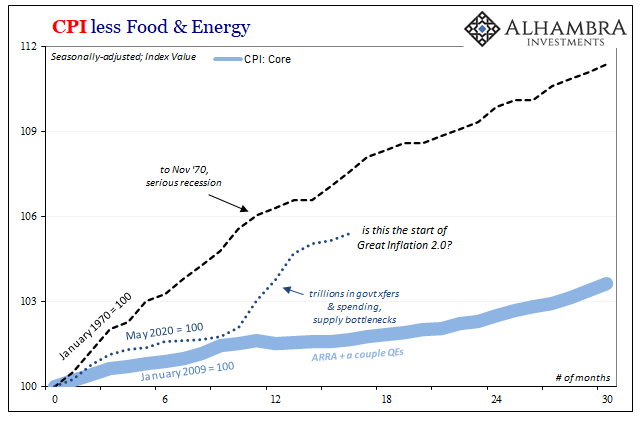

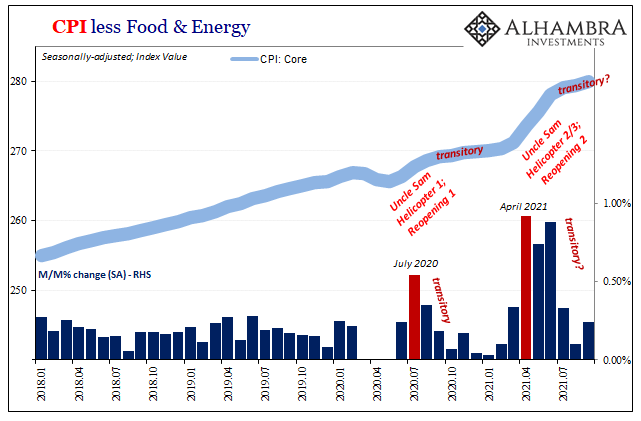

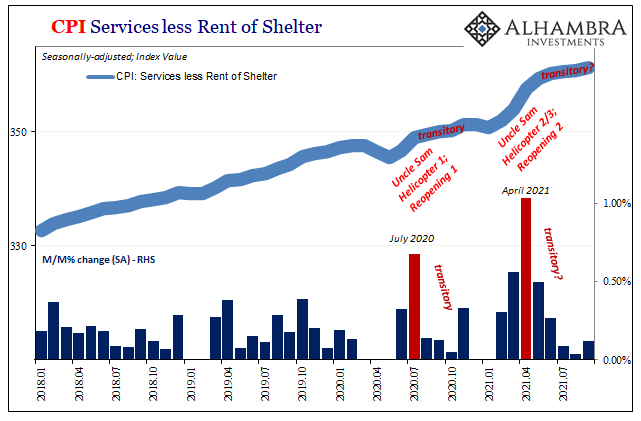

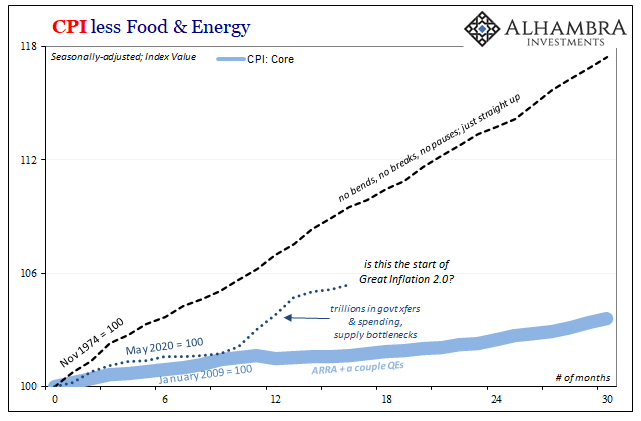

OK, so we went through the ways and reasons consumer price increases are not inflation, cannot be inflation, are nowhere near actual inflation, and what all that really means. The rate they’ve gone up hasn’t been due to an overactive Federal Reserve, so it has to be something else. This is why, though the bulge has been painful, it’s already beginning to normalize. Without a persistent monetary component (in reality, not what’s in the media) the economy will adjust eventually.

It already has. Several times, and that’s part of the problem.

If not money, and it’s not, then what is behind the camel humps? No surprise, Uncle Sam’s ill-timed drops along with reasonable rigidities in the supply chain.

An Economist might call this an accordion effect. One recently did:

The closures and reopenings of different industries, coupled with the surges and lags in consumer purchasing during the pandemic, have caused an “accordion effect,” says Shelby Swain Myers, an economist for American Farm Bureau Federation, with lots of industries playing catch-up even as they see higher consumer demand.

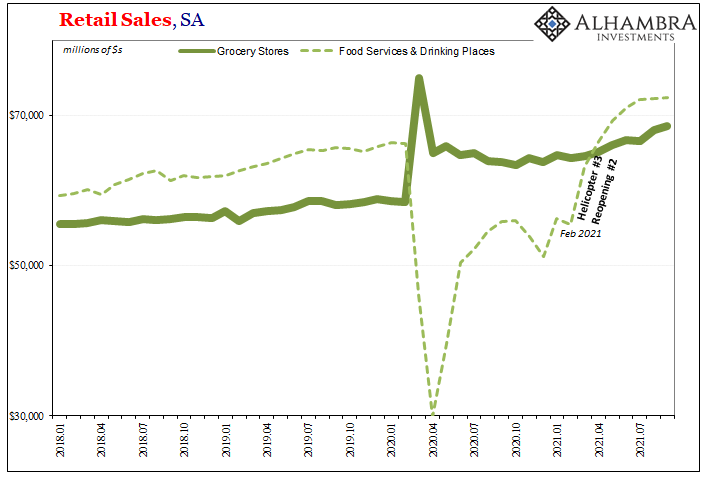

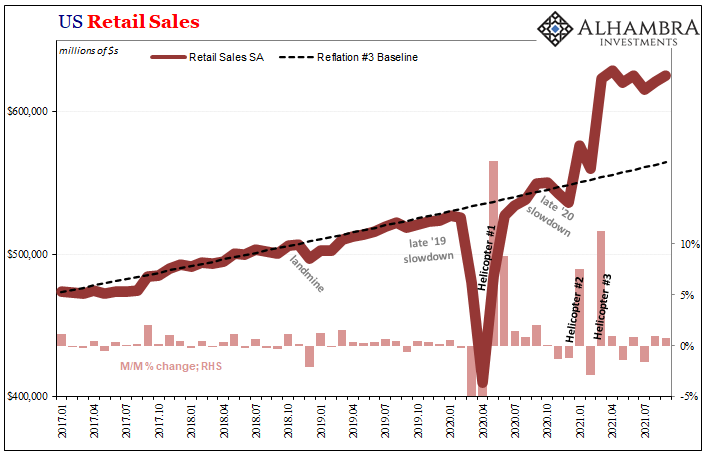

Not just surges and lags, but structural changes that have been forced onto the supply chain from them. With the Census Bureau reporting US retail sales today, no better time than now and no better place than food sales to illustrate the non-economics responsible for the current “inflation” problem.

When governments panicked in early 2020, they shut down without thinking any farther than “two weeks to slow the spread.” This is, after all, any government’s modus operandi; unintended consequences is what they do.

The food supply chain had for decades been increasingly adapted to meeting the needs of two very different methods of distributing food products; X amount of capacity was dedicated to the at-home grocery model, while Y had been set up for the growing penchant for eating out (among the increasingly fewer able to afford it). Essentially, two separate supply chains which don’t easily mix; if at all.

Not only that, food distributors can’t simply switch from one to the other. And even if they could, the costs of doing so, and the anticipated payback when undertaking this, were and are massive considerations. McKinsey calculated these trade-offs in the middle of last year, sobering hurdles for an already stretched situation back then:

Moreover, many food-service producers have already invested in equipment and facilities to produce and package food in large multi-serving formats for complex prepared-, processed-, frozen-, canned-, and packaged-food value chains. It would be highly inefficient to reconfigure those investments to single service sizes.

And if anyone had reconfigured or would because they felt this economic shift might be more permanent:

For food-service producers, the dilemma is around the two- to five-year payback period of new packaging lines. Reinvesting and rebalancing a food-service network for retail is not a straightforward decision. Companies making new investments would be facing a 40 percent or more decline in revenue. And any number of issues could extend the payback period or make investments unrecoverable. Forecasts are uncertain, for example, about the duration of pandemic-related demand shifts, the recovery of the food-service economy, and the timeline of returning to full employment.

So, for some the accordion of shuttered restaurants squeezed food distributors far more toward the grocery and take-home way of doing their food businesses. And it may have seemed like a great bet, or less disastrous, as “two weeks to slow the spread” morphed to other always-shifting government mandates which appeared to make these non-economics of the pandemic a permanent impress.

More grocery, less dining. Forever after.

In one famous example, Heinz Ketchup responded to what some called the Great Ketchup/Catsup? Shortage by rearranging eight, yes, eight production lines to spit out their tomato paste in individual servings rather than bottles. CEO Miguel Patricio told Time Magazine back in June (2021) there hadn’t actually been any shortage of product, just the wrong packaging for it:

It’s not that we don’t have ketchup. We have ketchup, but in different packages. The strain on demand started when people stopped going to restaurants and they were ordering takeout and home delivery. There would be a lot of packets in the takeout orders. So we have bottles; we don’t have enough pouches. There were pouches being sold on eBay.

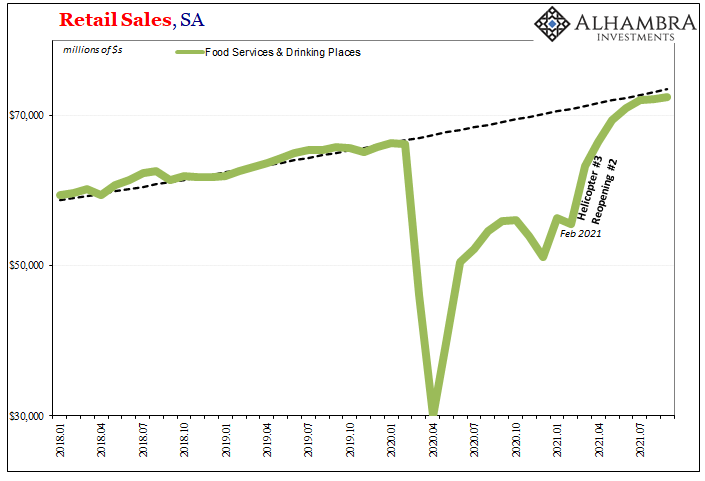

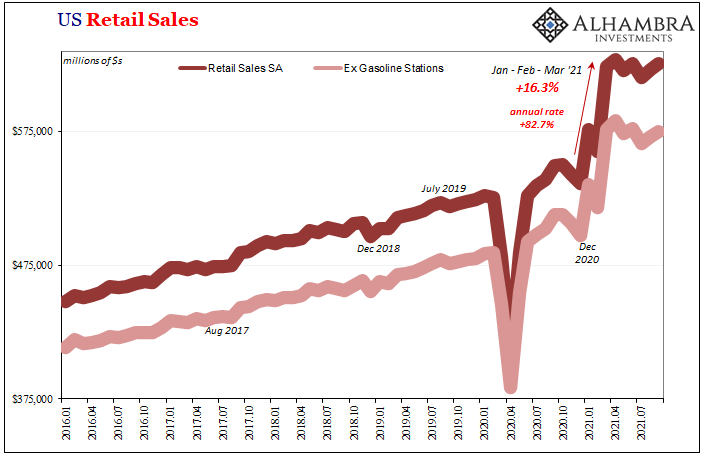

But then…vaccines. Suddenly, after over a year of the above, by April 2021 the doors were flung back open, stir-crazy Americans flew back to their local pubs and establishments (see: below) and within months, according to retail sales, it was almost back to normal again. Meaning pre-COVID.

The accordion had expanded back out but how much of the food services supply chain had been converted to serve the eat-at-home way which many companies had understandably been led to believe was going to be a lasting transformation?

Do they undertake even more costly and wasted investments to go back? Maybe they resist, just shipping what they have even if not fully suited in the way it had been before all this began.

Does Heinz spend the money to reconfigure those same eight production lines so as to revert to producing their ketchup in bottles? Almost certainly, but equally certain they’re going to take their sweet time doing it; milking every last ounce of efficiency – limiting their losses, really – they can out of what may prove to have been a bad decision (again, you can’t really fault Mr. Patricio for being unable to predict pandemic politics).

Rancher Greg Newhall of Windy N Ranch in Washington likewise told NPR that he has the animals, beef, pork, lamb, chicken, goat, but distributors are caught in the accordion (Newhall didn’t use that term):

NEWHALL: People don’t understand how unstable and insecure the supply chain is. That isn’t to say that people are going to starve, but they may be eating alternate meats or peanut butter rather than ground beef.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Newhall says he hasn’t had any issues raising his animals. It’s the processing and shipping that’s the bottleneck, as the industry’s biggest players pay top dollar to secure their own supply chains.

The usual credentialed Economist NPR asked for comment first tried to blame LABOR SHORTAGE!!! issues, including those the mainstream had associated with the pandemic (closed schools forcing parents to stay home, or workers somehow deathly afraid of working in close proximity with others) before then admitting:

CHRIS BARRETT: And there’s also the readjustment of the manufacturing process. As restaurants are quickly opening back up, the food manufacturers and processors have to retool to begin to supply again the bulk-packaged products that are being used by institutional food service providers.

With US retail sales continuing at an elevated rate, the pressures on the goods sector are going to remain intense.

Because, however, this is not inflation – there’s no monetary reasons behind the price gouge – the economy given enough time will adjust. And it has adjusted in some ways, very painful ways.

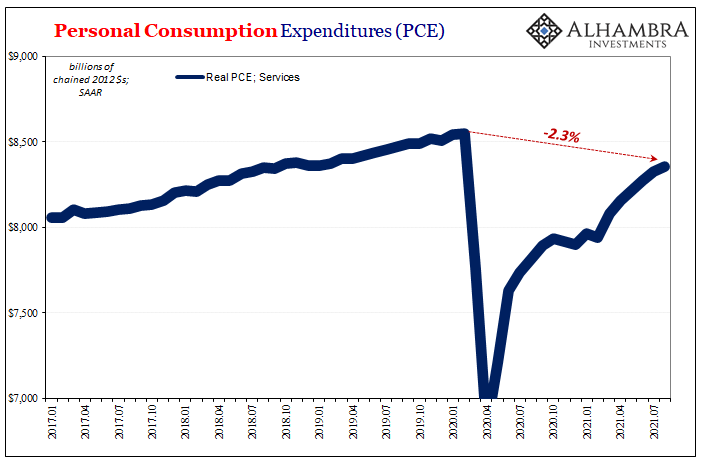

Painful in the sense beyond just hyped-up food prices and what we pay for gasoline lately, the services sector has instead born the brunt of this ongoing adjustment. Consumers have bought up goods (in retail sales) at the expense of what they aren’t buying in services (not in retail sales); better pricing for sparsely available goods stuck in supply chains, seeming never-ending recession for service providers.

According to the BEA’s last figures, overall services spending remains substantially lower than when the recession began last year. And it shows in services prices which had been temporarily boosted by Uncle Sam’s helicopter only to quickly, far more speedily and noticeably fall back in line with the prior, pre-existing disinflationary trend following a much smaller second camel hump.

Once the supply and other non-economic issues get sorted out, we would expect the same thing in goods, too. It is already shaping up this way, though bottlenecks and inefficiencies are sure to remain impediments and drags well into next year.

Those include other factors beyond food or domestic logistical nightmares. Port problems, foreign sourcing, etc. The accordion has played the entire global economy, and in one sense it has created the illusion of recovery and inflation out of a situation which in reality is nothing like either.

That’s the literal downside of transitory. We can see what the price bulge(s) had really been, and therefore what it never was.

Stay In Touch