It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

Some see the cup as half empty. Some see the cup as half full. I see the cup as too large.

George Carlin

The quote from Dickens above is one that just about everyone knows even if they don’t know where it comes from or haven’t read the book. But, as the ellipsis at the end indicates, there is quite a bit more to the line than the part everyone remembers.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

The book is set during the French Revolution but it does a pretty good job of describing our current condition. How you see the world is a function of your circumstances, some of which you control and many of which you don’t. There has never been one America, one that everyone perceives the same, but it certainly seems that today there are more versions of it than there have been in the past. This is true within a lot of spheres but maybe none so much as the economic one. COVID has made the divide between rich and poor, blue-collar and white-collar, that much more stark. There is the America of work from home and there is the America of essential workers. There is the America of shareholders and homeowners and there is the America of paycheck to paycheck. Or, increasingly during COVID, from stimulus payment to stimulus payment or unemployment check to unemployment check. The economy is in a very different state depending on your position in this hierarchy. For those of us who are able to keep doing our jobs from our spare bedroom, the last 18 months have, for many, been a boom time. For those in service businesses that were victims of the shutdowns, the last 18 months have been a time of high anxiety.

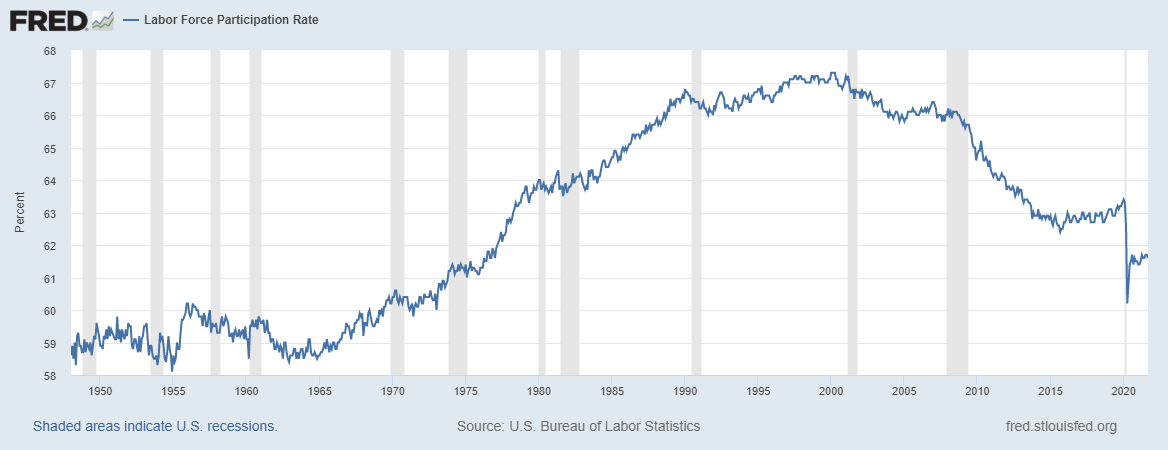

In truth, for many Americans, the high anxiety is not new. COVID merely accelerated trends that were already in place. Economic growth is ultimately about two things: workforce growth and productivity growth. Both have been weak for at least a decade and really quite a bit longer. The workforce has grown pretty steadily but the participation rate has been in decline for two decades. It did stop falling for a period from about 2016 to 2020 and had even started to rise again but COVID brought that short-term trend to an end.

This, almost by itself, is why US economic growth has been unsatisfying for so long. This is also the genesis of today’s “labor shortage”. We can see the effect weekly in jobless claims which recently dropped below 300k for the first time since the arrival of COVID. I heard someone say a few weeks ago, when the weekly total was 335k, that it was improving but still “elevated”. I’ve been doing this a long time and I’m getting old but my memory has not failed yet and that just didn’t seem right to me. So, I checked the history and indeed a level of 335k is actually pretty average even during the boom of the late 90s. In fact, since 1980 there have been 384 weeks with claims less than 300k and only 25.5% of them happened prior to 2014. There have been 247 weeks with claims less than 275k but only 3.6% of them happened before 2014. And there have been 162 weeks with less than 250k and none of them happened before 2014. That tells me that employers have been very reluctant to fire workers for a long time before COVID and the only reason I can think of for that is that they fear they can’t replace them.

Why is this happening? That is a question with many answers – it isn’t just one thing and I don’t think you can say that all of it is “bad”. Baby boomers retiring is not something that is bad (in most cases) and that is certainly part of this. Some portion of this, especially since the onset of COVID, is about couples reassessing their life and deciding that the cost of a two-income household is actually pretty high in ways that aren’t all economic. Some portion of it is due to the opioid epidemic (although I don’t think that is as large a part as is commonly believed). Some of it is due to an increase in the time people spend in college; 13.1% of the population has a master’s degree, up from 8.6% in 2000. There is also an anger – call it wealth inequality or elite snobbery or envy or just a sense of fairness, it’s all the same – that manifests itself in the political arena. The election of Donald Trump and the popularity of Bernie Sanders and socialism at the same time are merely two sides of the same populist coin. Both sides of the political aisle recognize that the average American worker is angry and increasingly adopting a Johnny Paycheck attitude toward their employers. Where they differ is in the solutions – although in some areas there seems little difference. The divide between Bernie Sanders’ and Donald Trump’s views on immigration is not discernible to the naked eye. And there is a reason you’ve seen almost no change in trade policy since the election of Joe Biden.

It is ironic too that the provision of fiscal largesse during COVID may have finally pushed the economy to a tipping point. With help wanted signs everywhere, labor appears to have finally gained the upper hand. 10,000 workers went on strike at Deere last week and 1400 are out at Kellogg. There may or may not be an intentional work slowdown/sickout going on at Southwest Airlines. 32,000 nurses are considering a strike against Kaiser Permanente. American Airlines pilots are picketing in Miami. A strike was barely averted in Hollywood by backstage workers after they got basically everything they asked for. It isn’t just union workers either as the Quits rate proved last week. I’ve written in the past about the surge in new business formations since the onset of COVID and that is part of this too. There’s a lot going on in the labor market right now and how it impacts the economy is almost impossible to say. At this point, rising prices are eating up wage gains but that may not last and if it doesn’t, then workers gains may turn into profit margin losses. Or it may be the spur for investments that improve productivity. Companies aren’t racing to perfect self-driving vehicles because they’ll be safer. They’re doing it because truck drivers are expensive and Uber drivers want health insurance.

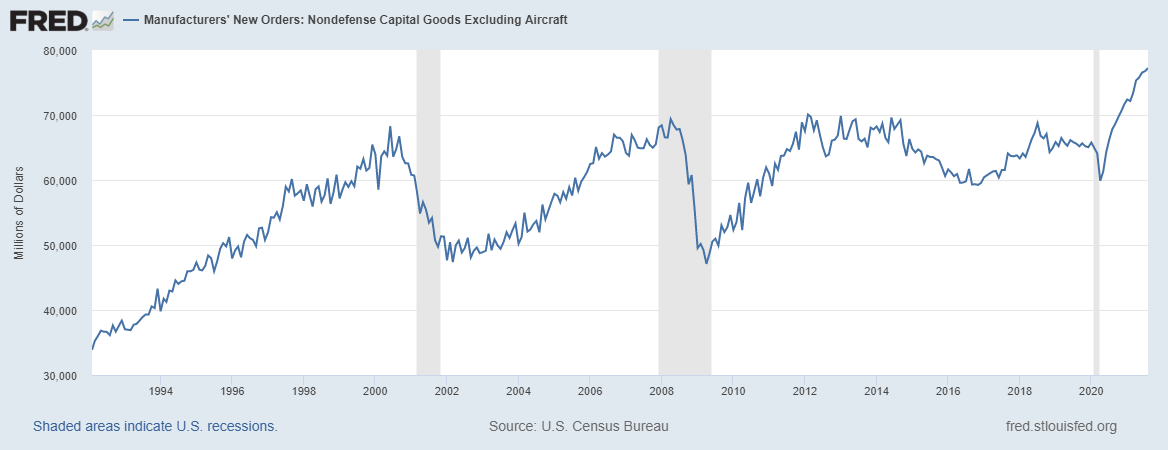

Productivity growth has also been weak but the change is less dramatic than in the labor market. Since 2000 annual productivity growth has averaged 1.9% down from 2.7% from 1995 to 2000, a period of high investment and innovation. That doesn’t seem like a big change but compounded over many years it has an impact. I think a better way to look at productivity growth is through investment in capital goods. Core capital goods (ex-defense and ex-transportation) show why productivity growth has stalled:

Core capital goods orders peaked in 2000 and didn’t exceed that peak for over 20 years. As you can see though, orders have recently broken through that old top. This may be the most important economic development in two decades.

I included the George Carlin quote above because it describes how I, as an investor, have to think about the economy. I am a pragmatist and have no expectations as to how things will unfold in the future. I don’t know why people are quitting their jobs and not taking jobs that are available. I assume there is some wage level where workforce participation would rise again but I don’t know what that level is other than to say that it is higher than what is being offered today (and it certainly isn’t just about wages). I would also say that if that wage level is so high that businesses can’t stay profitable when paying it, they will do something else, they will substitute capital for labor, they will find ways to operate with fewer employees. This may be why core capital goods orders are running higher right now. But I don’t know that and to be a good investor I can’t make assumptions. It is what it is.

This problem of perception versus reality is important for investors. Your reality does not necessarily bear on how the economy is perceived by the majority. Even objective reality doesn’t really matter for the markets in the short run – which can be a lot longer than you think. Markets tell us how the majority perceives it, not necessarily its real condition today. We have to invest based on that perception, not on reality, until we believe the gap between the two is so large that the current perception becomes untenable and has to shift to something new. And we need to understand that it is often the perception that creates the reality, the markets that shape the economy rather than the other way round.

At Alhambra, it is Jeff Snider’s job to describe the objective reality of the economy – how it really is. He is, however, human and so his perception of the economy is skewed by his own experiences and relationships. But he knows that and I know that and I think he does a pretty good job of describing the way things really are. We don’t always agree on how he describes it, the language he uses, but in general, I think he gets a lot more right than most of the people in our business trying to decipher the myriad human relationships that create an economy. But the reality he describes does not always align with how we invest. It is at turning points, when the gap between Jeff’s reality and the market’s perception get too wide, that his research bears most on our investment choices.

Right now, the dominant narrative in markets is about inflation. Jeff and I agree that what is happening today is not real inflation (a monetary phenomenon) but rather rising prices that are a result of the supply-side nature of the last recession. And in particular, it is a condition created by government intervention, as first the Trump administration and now the Biden administration applied demand-side government solutions to a – mostly – supply-side problem. In short, the real problem right now is not actually supply but rather that demand is excessive due to the largesse of government “stimulus” (there are exceptions to that such as semiconductors). It was certainly necessary to support those who were truly hurt by the pandemic shutdowns. Service workers who were put out of work by government diktat certainly deserved a helping hand from that government. But the payments to those who didn’t need it – and that was and continues to be (child tax credits) a large cohort – were unnecessary, counterproductive, and now hurting those who actually needed assistance. Rising prices hurt the poorest among us the most.

But the fact that today’s rising prices are from fiscal and not monetary excess is largely irrelevant to the markets and to individuals dealing with them. Investors are reacting to the “inflation” just as they would if it were driven by monetary factors. They are buying commodities, TIPS, and other assets they perceive will protect them from it. And in doing so, they change markets in ways that can affect the nature of the future economy. As an investor, it doesn’t matter if commodities are rising for the “wrong” reason. What matters is that they are and if you aren’t allocated there, you’re missing a source of return for your portfolio. It also doesn’t really matter whether some individual commodity isn’t participating in the rally or if the general commodity indexes are rising mostly because of energy. Investors aren’t focused on whether platinum or iron ore is going up. They are focused on “commodities”, on the idea that in inflationary times “commodities” go up and they want to own them.

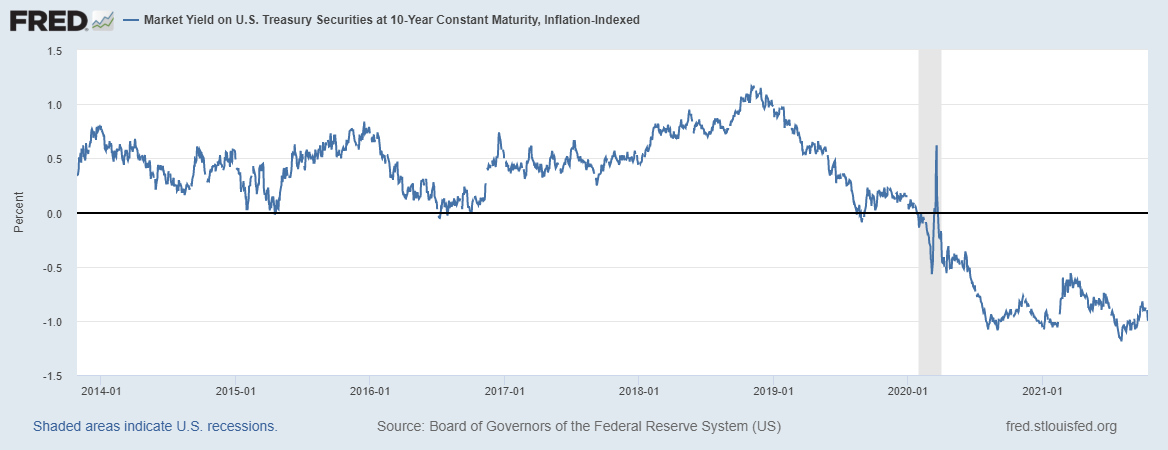

There is also an emerging perception, a narrative about economic growth right now, that it is accelerating as the delta variant fades. You can argue that COVID is a hoax or that delta didn’t really have much of an impact or that we’re going to get another wave in winter or whatever you want. But if the majority believes that economic growth is going to accelerate, that’s how they’re going to invest and you’re argument won’t make you a plug nickel. Investors right now are selling gold and buying copper. They aren’t doing that because they think the economy is going to slow. They aren’t selling bonds because they think growth is slowing either. Yes, they aren’t selling TIPS at the same rate as nominal bonds but that makes sense if you are worried about inflation and also think the economy is going to accelerate. We saw this last year when rates rose too; nominal rates initially went up a lot faster than TIPS yields. But eventually, TIPS caught up because growth did accelerate. Will we see the same thing again? I don’t know but it certainly isn’t outrageous to think so and a lot of people do.

Our economy, the global economy, is undergoing a profound shift right now. Some of the trends that were in place prior to COVID have accelerated (labor market) and some may be reversing (investment and productivity). I do not believe there is any way to know how these changes will shape our economy and markets in the coming years. Periods of economic upheaval like the last twenty years are always disconcerting, disorienting to those going through them. But similar periods in the past have also produced great innovations, big changes to the social and economic fabric of a nation. What those changes are will be revealed by the markets, through the perceptions and actions of investors, long before they are obvious. It’s going to be an interesting time for sure.

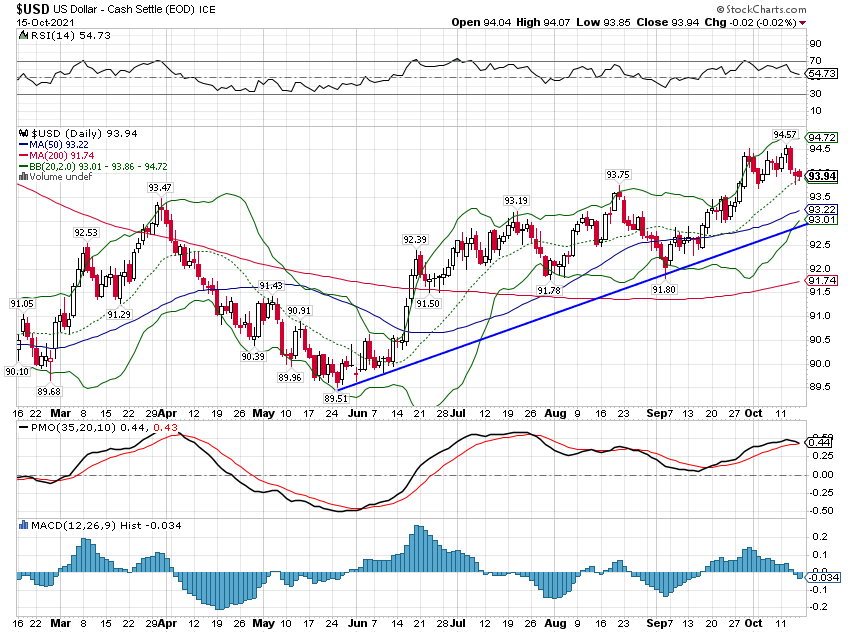

The emerging narrative about a Q4 economic acceleration gained some credence last week as the copper/gold ratio rose over 4%. Despite that move, I am not changing our economic environment assessment yet. The current level is about as high as it has been able to get since 2008 and absent a shift to a declining dollar, I question whether it can go much higher. I am also skeptical of shifting to rising growth until we see a more decisive move higher in TIPS yields. The emerging economic acceleration narrative is exactly that – still emerging.

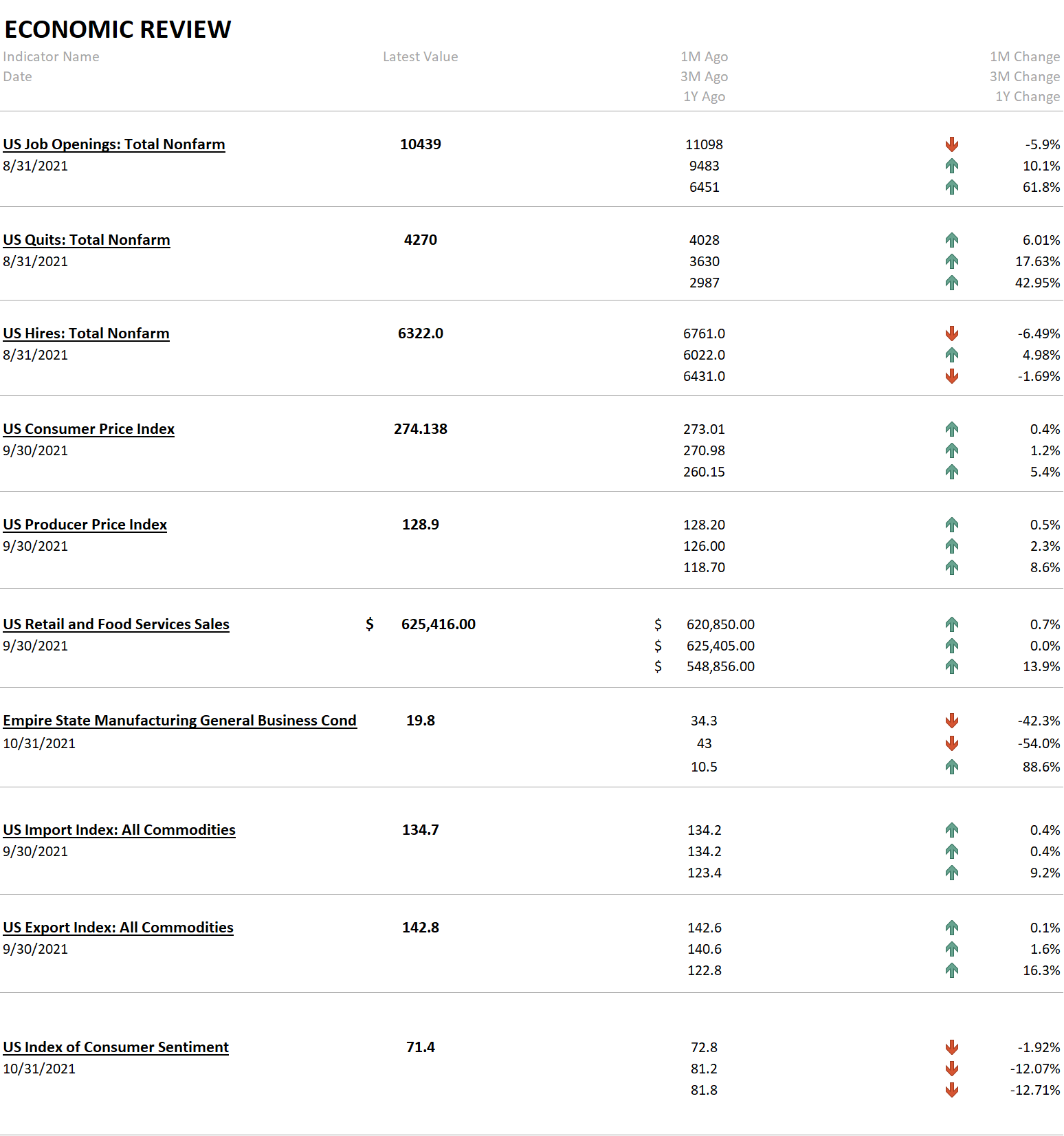

Job openings fell in August but are still historically high. Hires also fell but quits continued to rise. None of this is actually news since we’ve gotten plenty of other data on the labor market since August. But it does confirm what we already believed about the labor market.

The inflation data was wholly unsurprising and added nothing to the ongoing inflation debate.

The retail sales data was a big upside surprise though and will feed the accelerating growth narrative even though an inflation-adjusted view isn’t as robust. Consumer sentiment continues to support the slowdown view but the idea that we’re near or entering recession – as some prominent economists speculated last week – seems a bit over the top.

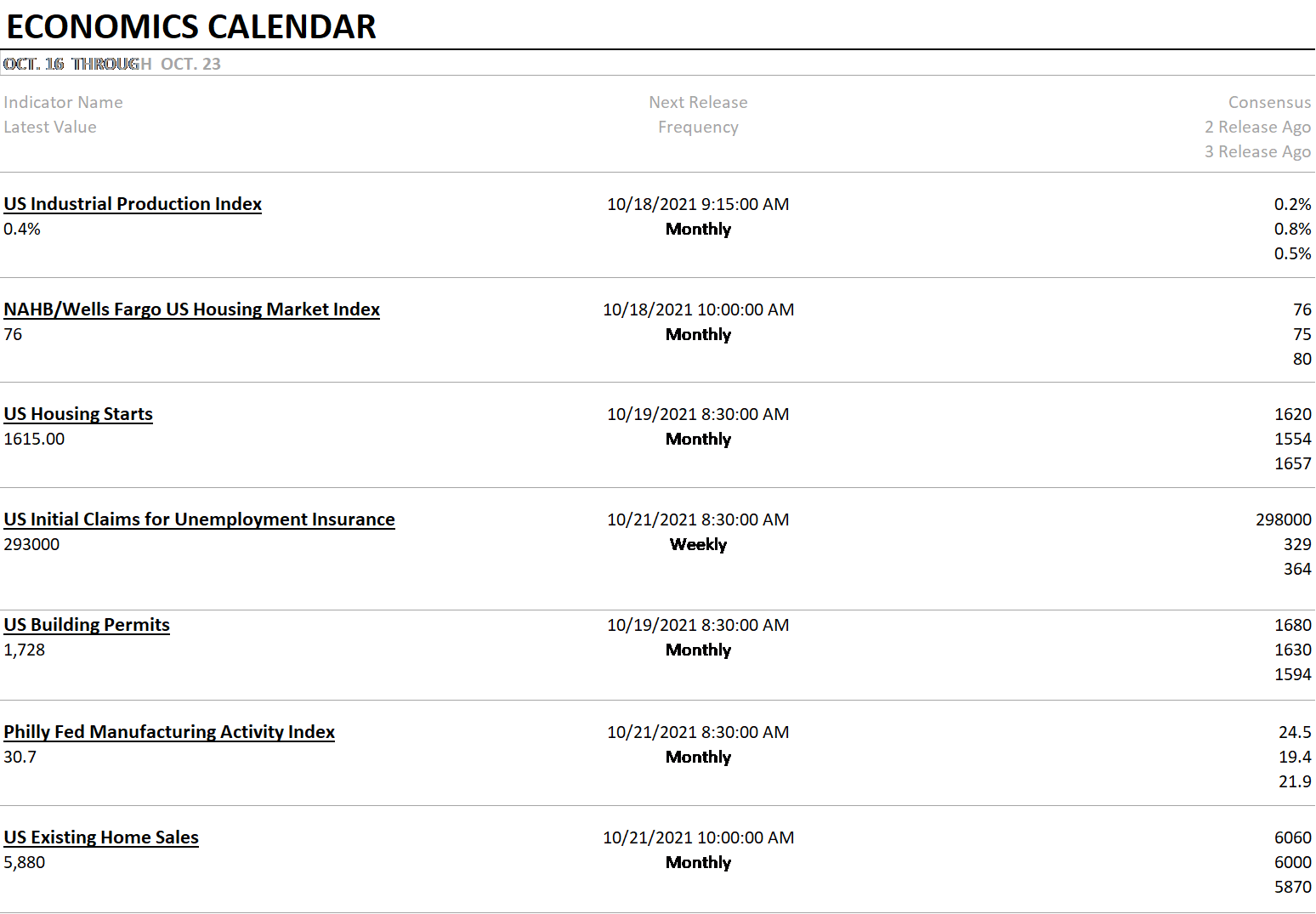

We get more housing data this week and it will be interesting to see if there is any pickup. Based on my very unscientific method of talking to realtors and homeowners around the country, the housing market is cooling rapidly.

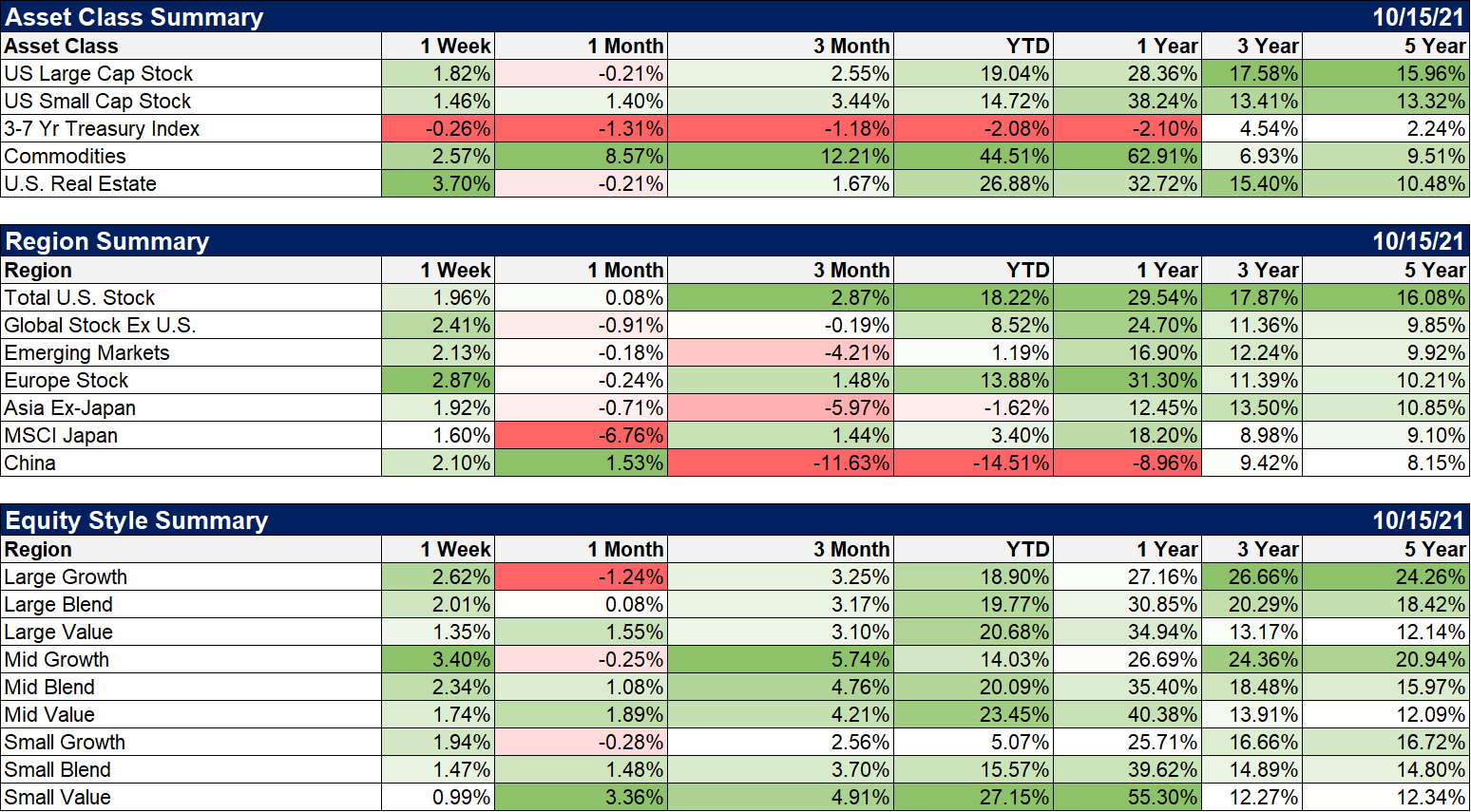

Stocks were up last week but the inflation side of the portfolio did even better with real estate and commodities both producing higher returns for the week. Non-US stocks also outperformed as the dollar fell slightly.

Growth took the lead for the week but the trend back to value seems intact.

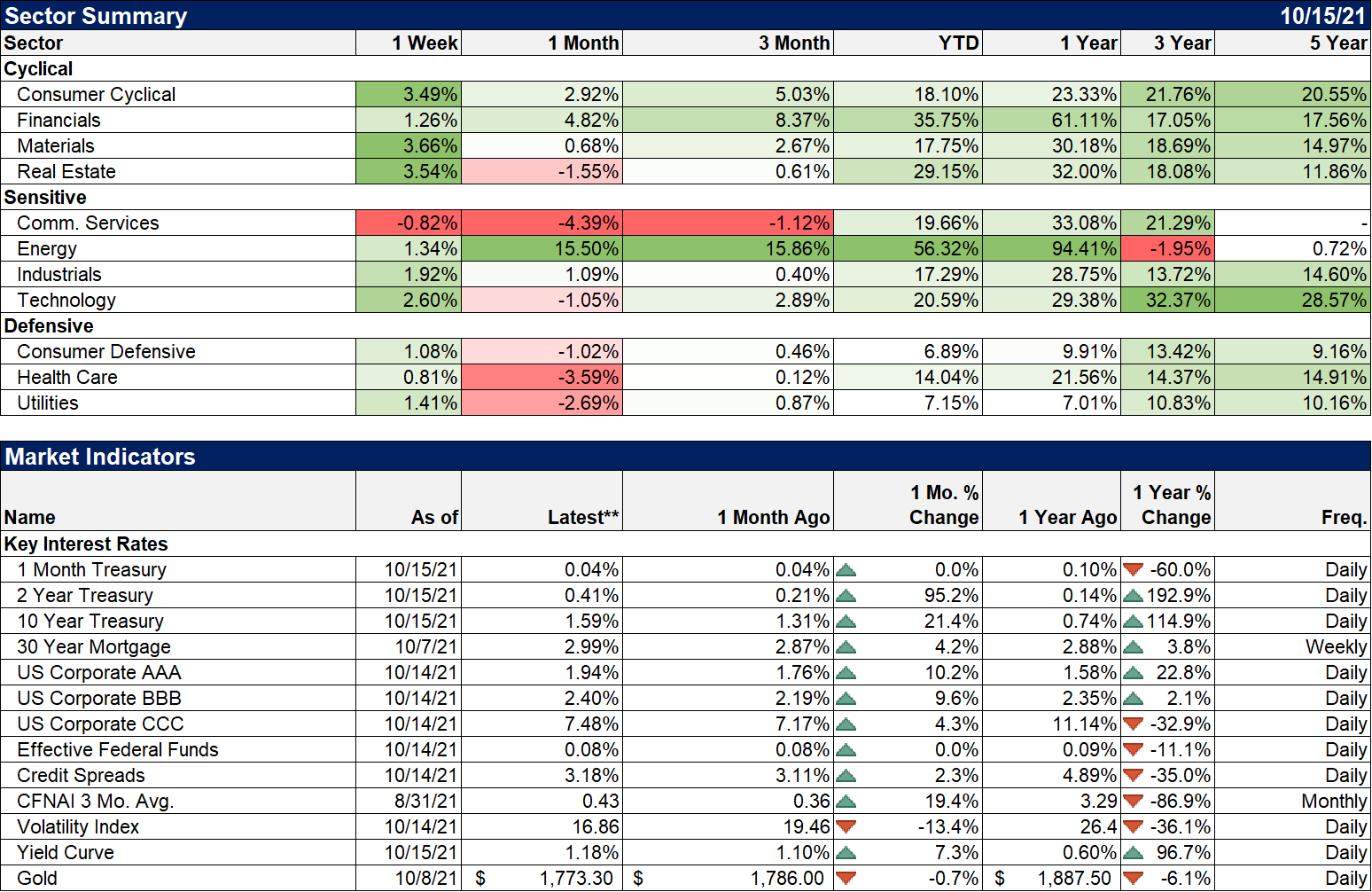

Cyclicals and inflation-sensitive sectors (real estate, materials) led the way last week.

Please note that I’ve added some new items at the bottom of this chart.

I have said many times that an investor’s job is not to predict the future but to interpret the present. Predicting the future is impossible but interpreting the present accurately isn’t as easy as it sounds. Today’s debate about inflation and economic growth and labor shortages certainly proves that by my reckoning. Is there a labor shortage? Is this inflation or is it some transitory thing that will fade as fiscal stimulus fades? Are those who had their unemployment benefits run out applying for open jobs? Is economic activity accelerating as delta fades or was the slowdown caused by something else? These are all questions about the state of the economy today, not in the future. And frankly, we don’t have very good answers for them. What markets are doing today, how people react to these things, will impact the outcome. What looks like a supply/demand imbalance causing prices to rise today could shift to something more permanent and monetary if it causes people to lose confidence in the Fed and subsequently the dollar. The long-term health of the economy may improve because workers who refuse to work today cause companies to invest in productivity-enhancing technology. Perception creates reality. Invest accordingly.

Joe Calhoun

Stay In Touch