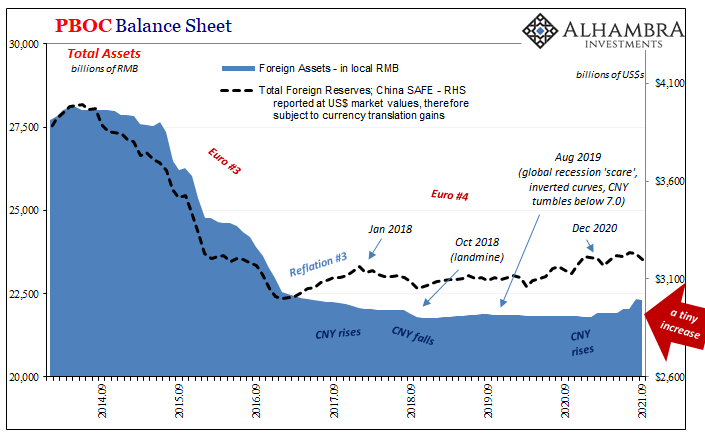

For several years now, we’ve been harping constantly and consistently about what’s on the PBOC’s balance sheet; or, really, what conspicuously isn’t in very specific line-item numbers. Briefly, simply, if dollars are being extended into China, as has been claimed over the years, particularly the last few, they’re going to show up on the Chinese central bank’s balance sheet.

Specifically, foreign assets. More specifically, foreign reserves.

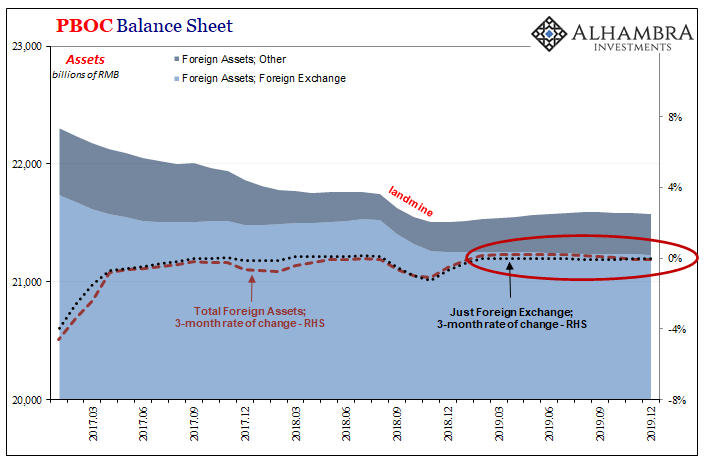

There’s a difference between those two which historically has meant quite a bit (we’ll get to that in a moment). Going back to 2017 and 2018, the level of foreign assets (which includes reserves) has been beyond stable, constant to the point of clear manipulation. As I wrote last year:

According to the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the balance of foreign assets reported on its balance sheet for the month of June 2020 was RMB 21,833.26 billion. At the end of the prior month, May, the balance was, get this, RMB 21,833.33 billion.

Rampaging global pandemic, dollar crashing, dollar smashing, global recession questions, massive, complex economic forces to go along with huge changes in financial conditions, as well as questions about those conditions, and the Chinese system pretty much in the middle of everything. The second largest economy in the world, one which is made (and broken) by incoming (or outgoing) monetary flows of which the central bank has involved itself heavily right from the very start of modern China.

And foreign reserves on the central bank balance sheet, the fundamental basis by which Chinese money exists, this moved by the tiniest RMB 70 million? In case you are wondering, it works out to a monthly change of -0.0003%. Nuh uh. No way. That’s a number which was quite obviously engineered.

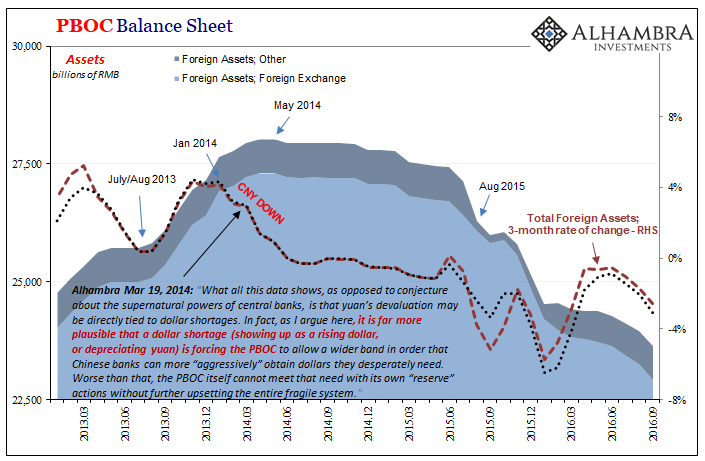

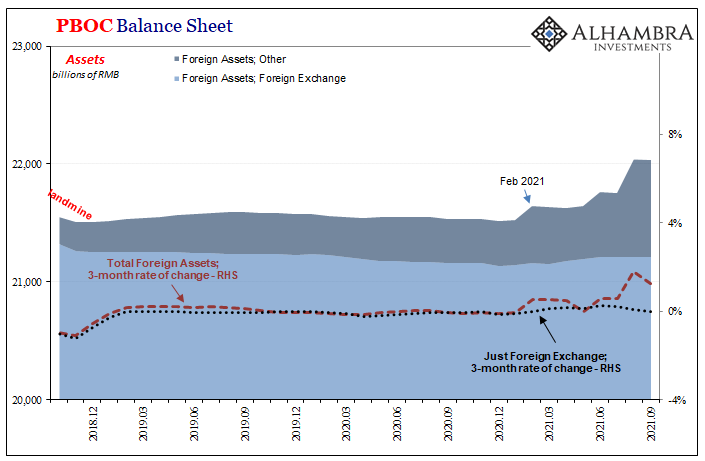

Just about sums the whole thing up; as does this chart:

What should grab your attention is the slight, though somewhat more noticeable increase in reported foreign assets during this year. We’re being asked to believe this is Jay Powell’s flood of “too much” money finally making its way into the right places; and this general data from China seems to be at least some level of consistent with the idea.

Once you get into the details, though, what’s going on over at the PBOC actually adds to the evidence of its opposite. Dollar problems, scarcity, maybe even growing and outright global money shortage.

Before we get to that, however, we have to back up and review those details. To do that, we’ll begin all the way back in the pre-crisis period when “too much” eurodollar money was a legitimate, provable condition worldwide.

Dollars between 1995 and 2007 were in such worldwide overabundance even the monetary illiterate like Ben Bernanke couldn’t help but notice them – though, captured by his rigid and rigidly incoherent ideology, the Federal Reserve’s Chairman could only muster some nonsense about a global savings glut.

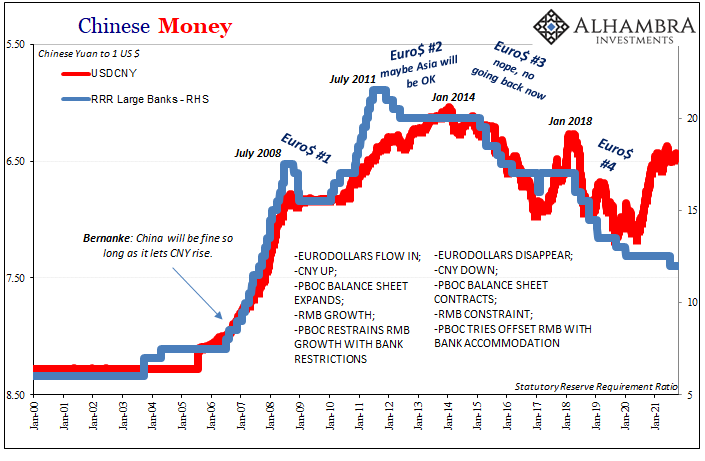

His Chinese counterparts suffered no such illusions, being forced by the monetary onrush to alter both banking and monetary policies for this “hot money” excess. Up until August 2007, that is. No, this is not a coincidence.

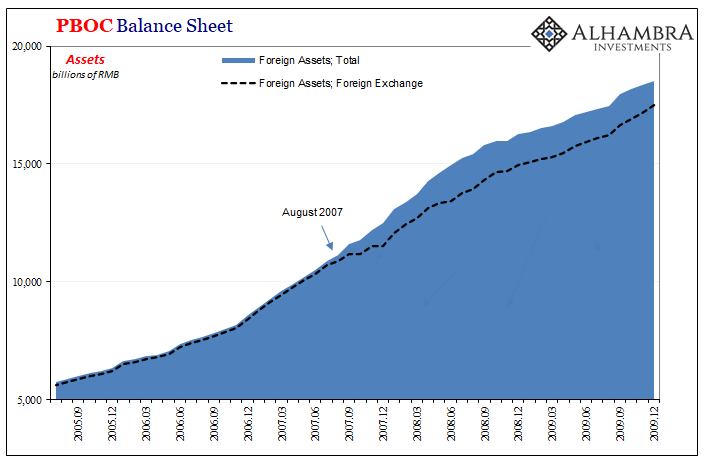

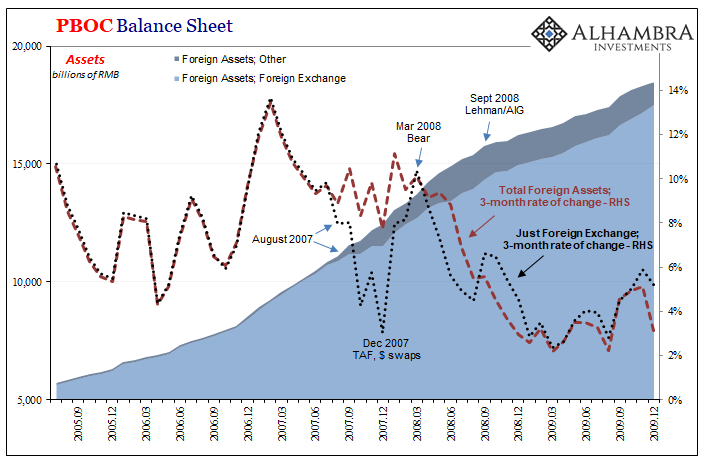

Start with the rising blue mass above which is the PBOC’s definition for all its various foreign assets. I’ve then added the dashed black line to begin breaking out the precise pieces within the category. This line represents that vast majority – but not all – of foreign assets, labeled by China’s central bank as “foreign exchange.”

The remainder is left to two other classes. The first is official gold holdings, which for our purposes we’ll ignore (as much as it pains me, the real world ignores it, too). What’s left is what’s always left over in these things: other foreign assets.

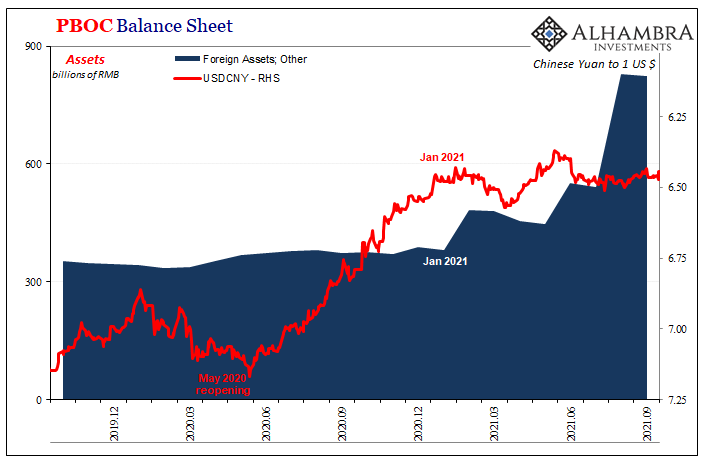

It’s in this “other” where both the fun and monetary literacy begin.

The implications are pretty obvious, as are their connection to the burgeoning Global Financial Crisis in a way that pegs said crisis as the only thing it could have ever been: a global dollar shortage. Not subprime mortgages, a systemic rupture in the bank-centered eurodollar system so bad it forced even invulnerable China into some visible countermeasures.

And here (above) you can see one of those: other foreign assets. What is other? Your guess is as good as mine (OK, maybe I might have a slightly better idea having spent enough time poking around, but even then not so much better because this stuff is left opaque by Communist design). For right now, “what” doesn’t matter.

It does matter that whatever it might be that is in “other”, this shows up at the exact moment the global dollar rupture hits in August 2007. Immediately, two things pop out on the PBOC’s balance sheet: fewer foreign exchange assets but more of other. Eurodollar shortage, fewer dollars organically register as foreign exchange.

In lieu of market-based dollars, though, look what happens to the growth of total foreign assets which is maintained at a nearly constant growth rate by the addition of other foreign assets. It is a workaround, a fill-in to keep up the flow at the margins. A rescue, of sorts, to buy some time for the eurodollar world to normalize.

For the first few months of 2008, there seemed to be some hope the Federal Reserve’s (how naïve everyone was) “rescues” could work (TAF, overseas dollar swaps “somehow” being overbid by US banks with mostly German names). Foreign exchange pops back up for the PBOC – but only until March 2008.

Bear Stearns.

Taking a guess as to “contingent liabilities” within “other”, Bear was the final straw for China as most of the rest of the world. Too expensive to maintain, Chinese authorities realized they’d instead have to ride out the growing (not past tense) storm; they’d have to switch to other even more opaque tactics unreported anywhere.

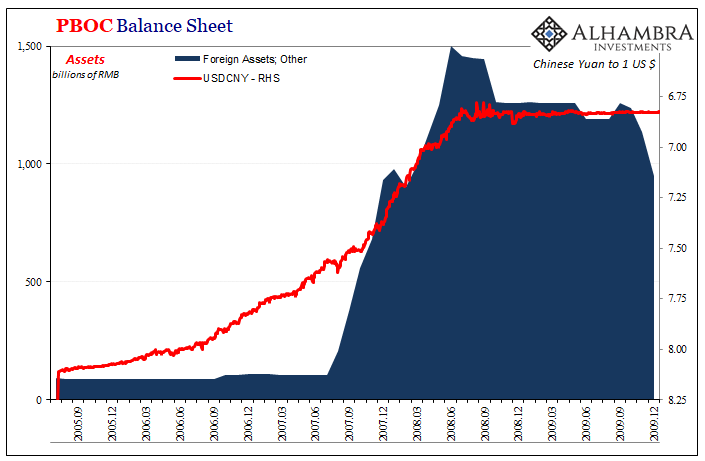

After trying to offset the first phase of the GFC1 dollar shortage with “other”, the Chinese then moved to a completely stealth CNY peg (stealth because the back half of whatever transactions don’t show up anywhere). You can see this two-step above; first the jump in “other” while CNY still rises, then total CNY peg as foreign exchange assets stop growing at the same fast pre-crisis rate.

Unlike “new normal” America and Europe, the Chinese emerged from the ensuing Great “Recession” believing their situation/potential hadn’t been altered. A big enough chunk of the eurodollar system seemed to agree – for a time.

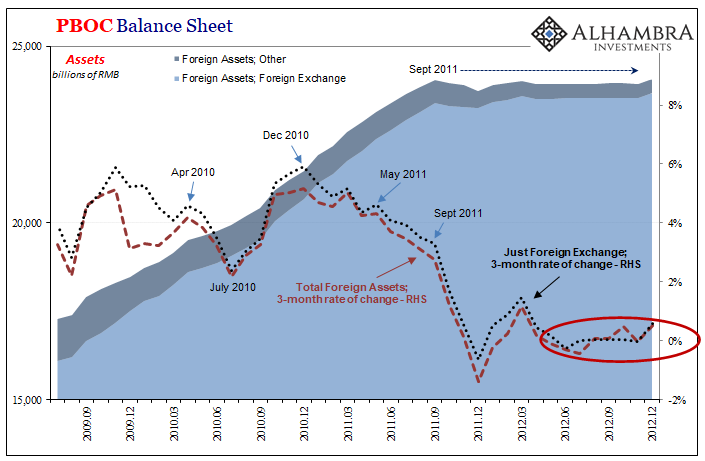

Chinese monetary authorities spent 2010 and most of 2011 letting these “other” foreign assets roll off the balance sheet; if actually contingent liabilities, then repaying, terminating and getting out with CNY rising likely making the repayments and retirements economical (and worth whatever cost, so long as nothing really changed for China’s long run).

But, as you can see (two above), a second eurodollar problem erupts in 2011 while the PBOC is still unwinding whatever it had done from late 2007/early 2008. While this meant another stoppage in inbound eurodollar flows, China’s economy appeared able to weather the breakdown (which was focused more on Europe) and with CNY still rising no emergency monetary measures appeared necessary (there was a fiscal “stimulus” package).

At least none of the same outward type which might end up in “other” foreign assets; something else was being done, from September 2011 forward, monetary officials clearly began pegging the aggregate foreign exchange balance on the PBOC’s balance sheet.

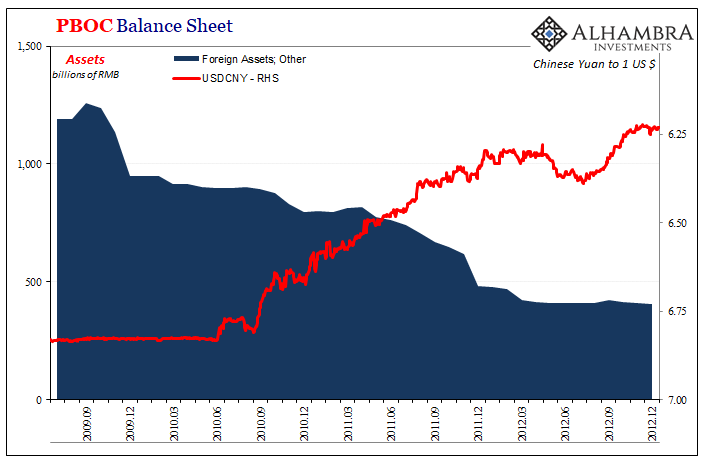

The Chinese weren’t so lucky by 2014. Although dollar inflows were restored in 2013 (Reflation #2), there was a serious break during that summer (Summer of SHIBOR) which was consistent with a then emerging emerging market currency crisis (dollar shortage) wrongly blamed on the “taper tantrum.”

Right from the start of the following year, dollars began to disappear again (falling foreign exchange). Already having introduced another batch of “other” intervention right in January 2013, officials instead went back to stealth CNY manipulation (ticking clocks).

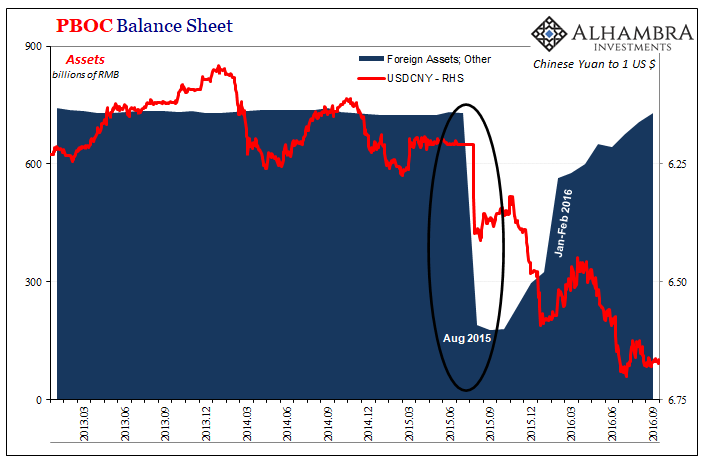

It didn’t work, either, as China suffered massive dollar destruction which then caused internal RMB destruction (bank reserves and currency). The freight train of Euro$ #3 hit the system by August 2015, causing CNY to plummet all-at-once, even triggering a flash crash across global stock markets within two weeks from yuan’s crash.

Perhaps understanding what was coming, the PBOC simply got the hell out of its way rather than risk being further sucked into the rising negative money vortex:

A demonstration how even other foreign assets are more like a last resort kind of thing.

The central bank would stay out of the eurodollar’s way until early 2016, coming back in because of the immensely costly damage done to CNY, the RMB system, as well as China’s and the global economy as a whole. The start of ’16 one of those situations that really did demand another last resort.

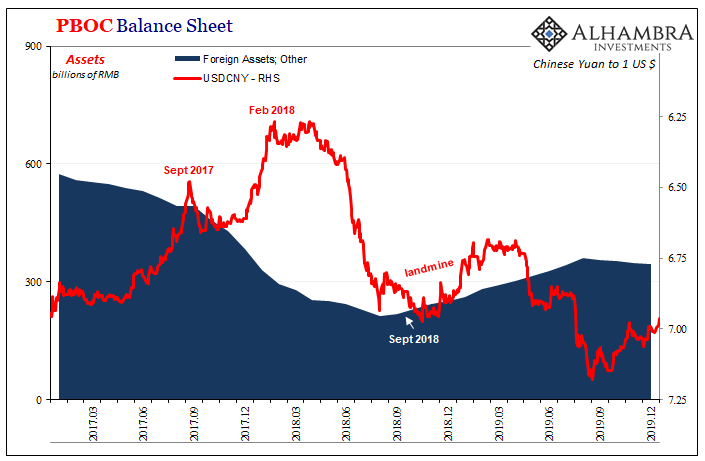

When confronted by the next one, Euro$ #4, again a clear reluctance to appeal to “other” foreign assets. There had already been a lack of dollars coming back, very few, anyway, during Reflation #3 (2017’s absurdly weak “globally synchronized growth”) leaving China dollar exposed to begin 2018.

Through the middle of 2018, once again the PBOC relied on this other peg to its aggregate foreign exchange balance in the same way it had back in 2012. Only this time, CNY was dropping like a stone, with officials apparently content to accept that outcome.

By October 2018, however, the situation must’ve been judged untenable, at least substantially more serious and dangerous, such that “other” foreign assets began to rise slightly but clearly to somewhat offset foreign exchange assets then declining.

The stealth peg to PBOC’s foreign exchange must’ve been overwhelmed by Euro$ #4’s late 2018 landmine. In its aftermath, CNY would eventually decline more in 2019 despite the offset in China’s “other” foreign assets, as this globally synchronized deflation wore down economies and markets (repo) all over the world.

What does all this mean?

Quite a lot of things we don’t have time or space to get into here, some different things, but among the commonalities is how “other” foreign assets continuously represent a last ditch kind of rescue or at least attempted offset to what therefore has to be among the more serious of already serious dollar shortages. There is no question how these results all fit together.

And, as I began at the outset, it is intuitive. If dollars are actually coming in, in reality rather than Jay Powell’s lying mouth, they show up at the PBOC as foreign exchange.

If they aren’t coming in, China’s balance sheet begins to break down in these specific ways, including, at key times, some sort of increase in other foreign assets.

This brings us back, and up to speed, with the first chart I presented. There has been an increase the PBOC’s reported holdings of total foreign assets which at first might appear on the surface as at least some trickle from the “too much” money we’ve heard all year about. It’s not.

What is it? Other foreign assets. Near entirely:

Foreign exchange assets gained the tiniest sliver, but since June (when CNY went sideways) nothing.

Instead, other foreign assets have picked up going all the way back to January. Yes, the same January.

This January:

There are obviously screwy things going on with the PBOC’s balance sheet, already on top of already screwy things (why a straight line for foreign exchange) that aren’t as obvious. And we know that screwy stuff corresponds religiously to monetary shortages, another eurodollar problem rather than whatever it is Jay Powell is telling the media to report to the public.

Odd developments which long predate delta COVID, aren’t trade wars or subprime mortgages. It’s the same thing repeating since all the way back in August 2007. Again, no coincidence “other” foreign assets showed up at exactly the same moment the eurodollar system broke.

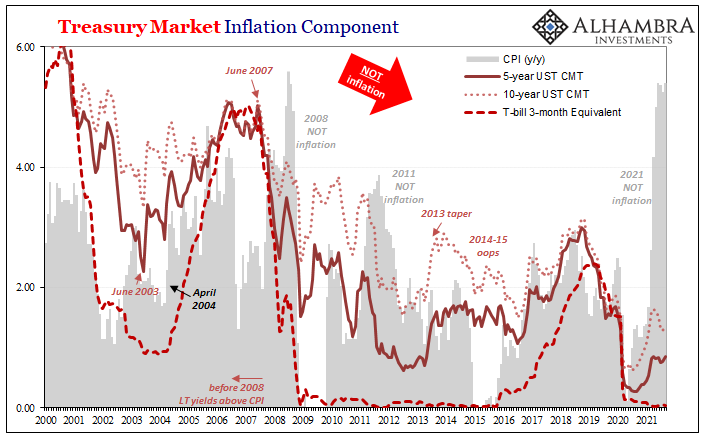

The mainstream theme or narrative for 2021 has all year been inflation, inflation, inflation. In actual monetary terms, which is what inflation must be, shockingly it’s actually been the whole opposite: deflation, deflation, deflation.

You don’t have to take my word for it. The evidence if everywhere (just start with bonds).

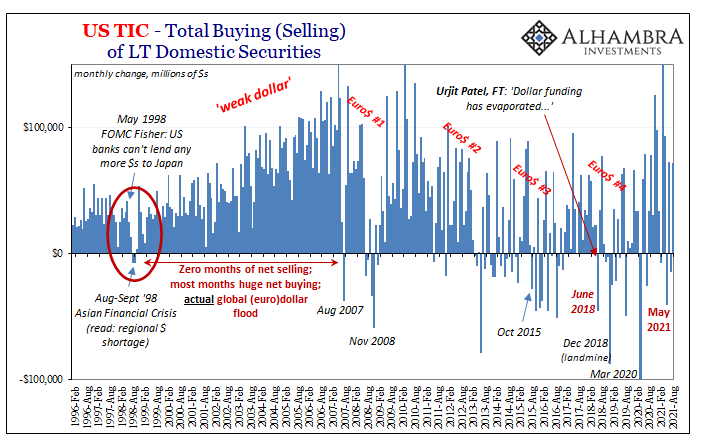

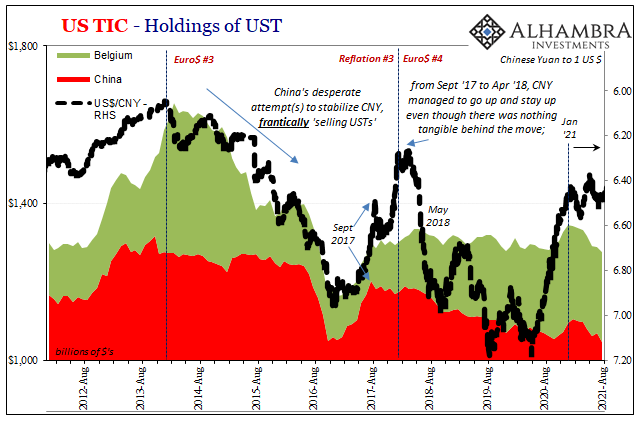

Whereas the TIC data is pretty unambiguous about this situation, the PBOC confirms the same from its own figures which are, once you orient them properly, only slightly less explicit even if we have no specific idea the exact transactions the Chinese are being forced into. Yet again.

Whatever those are, China sure isn’t being compelled to undertake them because there’s too much money in what remains the eurodollar’s world.

Stay In Touch